Community

Golf as big help in charity? Not so much this year.

Of all the economic areas devastated around the world by COVID-19, it’s probably fair to place the combination of charity and golf near the top of some lists.

Year after year, thousands of scramble tournaments are incredibly valuable: they’re a sports-lover’s way to raise funds for virtually every worthwhile cause under the sun. Lining up from June until late summer and beyond, service clubs, large and small companies, political groups, religious organizations line up to do their bit. Often, it’s more than a little bit.

Telephone calls and emails go out early and often. Committees scour the region to find inducements most likely to encourage participants to play at a nearby course for a reasonable price – with the understanding that some gifts will be granted and a lot of steaks will be eaten. But the big winners will be parts of the public that, it seems, always need and deserve more help than the existing welfare system can provide.

Celebrities are certain to get a lengthy list of playing opportunities. Having Edmonton Oilers or Edmonton Eskimos set for a tee time is one way to attract additional players and therefore additional funds. Former defensive back Larry Highbaugh once said he he had enough invitations to play in a separate tournament each week all summer. Entertainment personalities have special value, as well.

One tournament, conducted so far for nearly 20 years by the Cosmopolitan Clubs of St. Albert, Edmonton and Sturgeon Valley, is far from the largest or most significant of these events, but for 15 years club members were kind enough to label it The John Short Classic.

My thoroughly enjoyable contribution on the second Tuesday of June for 15 consecutive years was to greet players and needle volunteers. The tournament could be called a classic only on condition that I did not touch a golf club with serious intent. Fact is, I love golf far too much to desecrate it by playing as badly as I do. Good friend Rod Randolph, a key part of the Cosmopolitan commitment for more years than I was, once told me of a sure-fire way to get early attention at a coming speech: “show them your golf swing.”

Hockey Hall of Famer Marcel Dionne and former Oiler great Dave Semenko played in that tournament. Rob Brown, once a high-scoring linemate of Mario Lemieux, found ways to contribute on several Tuesdays – most of which were soggy and cold and windy, perfect opportunities to enjoy the outdoors and benefit others.

It is a daunting task to estimate how many of these charitable tournaments take place on the Edmonton region’s 50-or-so golf clubs each summer. Or how many will finally take shape this year. But personal knowledge of The Ranch, Stony Plain and Cougar Creek provides assurance that when conditions change, local professionals will be ready with open dates for these valuable events.

Early word is that area courses are in great shape. Randolph applied the adjective when describing his 84 after 18 holes on Wednesday at Mill Woods in a Men’s League game. “Not bad,” he said. “A pair of 42s when I’ve been collecting rust for seven months; I can deal with that.” Like a lot of golf addicts, he can deal with almost anything – except another shutdown.

Community

Support local healthcare while winning amazing prizes!

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Community

SPARC Caring Adult Nominations now open!

Check out this powerful video, “Be a Mr. Jensen,” shared by Andy Jacks. It highlights the impact of seeing youth as solutions, not problems. Mr. Jensen’s patience and focus on strengths gave this child hope and success.

👉 Be a Mr. Jensen: https://buff.ly/8Z9dOxf

Do you know a Mr. Jensen? Nominate a caring adult in your child’s life who embodies the spirit of Mr. Jensen. Whether it’s a coach, teacher, mentor, or someone special, share how they contribute to youth development. 👉 Nominate Here: https://buff.ly/tJsuJej

Nominate someone who makes a positive impact in the live s of children and youth. Every child has a gift – let’s celebrate the caring adults who help them shine! SPARC Red Deer will recognize the first 50 nominees. 💖🎉 #CaringAdults #BeAMrJensen #SeePotentialNotProblems #SPARCRedDeer

s of children and youth. Every child has a gift – let’s celebrate the caring adults who help them shine! SPARC Red Deer will recognize the first 50 nominees. 💖🎉 #CaringAdults #BeAMrJensen #SeePotentialNotProblems #SPARCRedDeer

-

Alberta7 hours ago

Alberta7 hours agoAlberta Independence Seekers Take First Step: Citizen Initiative Application Approved, Notice of Initiative Petition Issued

-

Crime6 hours ago

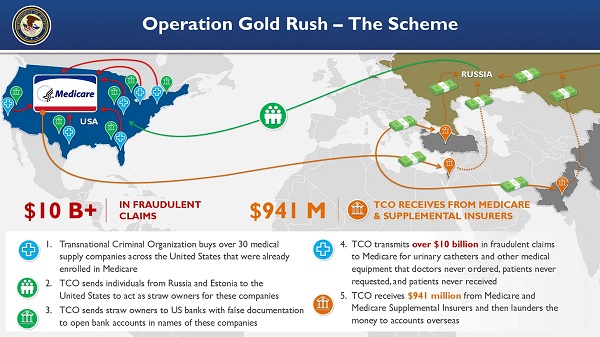

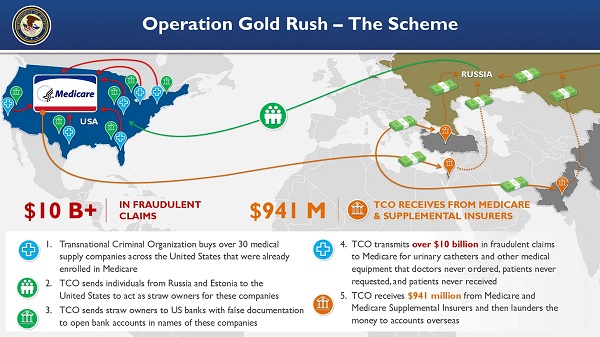

Crime6 hours agoNational Health Care Fraud Takedown Results in 324 Defendants Charged in Connection with Over $14.6 Billion in Alleged Fraud

-

Health5 hours ago

Health5 hours agoRFK Jr. Unloads Disturbing Vaccine Secrets on Tucker—And Surprises Everyone on Trump

-

Bruce Dowbiggin8 hours ago

Bruce Dowbiggin8 hours agoThe Game That Let Canadians Forgive The Liberals — Again

-

Alberta1 day ago

Alberta1 day agoCOVID mandates protester in Canada released on bail after over 2 years in jail

-

Crime2 days ago

Crime2 days agoProject Sleeping Giant: Inside the Chinese Mercantile Machine Linking Beijing’s Underground Banks and the Sinaloa Cartel

-

Alberta2 days ago

Alberta2 days agoAlberta uncorks new rules for liquor and cannabis

-

armed forces1 day ago

armed forces1 day agoCanada’s Military Can’t Be Fixed With Cash Alone