Alberta

Six stories from local soldiers who have deployed internationally in the past year

In the year that has passed since the last Remembrance Day, six soldiers from our local army units have deployed on international missions to Ukraine, Lebanon, and Latvia. They were asked a series of questions recently to get a sense of what they do on these missions and what they’ve learned, both about themselves, their mission, and the countries that they deployed to.

By way of background, Red Deer’s Cormack Armoury is home to 41 Signal Regiment, (2 Squadron), a communications unit, and 78th Field Battery, an artillery unit, along with army, air, and sea cadets.

The following are transcripts of interviews with each of them upon their return.

Major (Maj) James Gascoyne, 41 Signal Regiment

Major Gascoyne deployed to Ukraine

Mission name and country deployed to: Operation UNIFIER, Ukraine (Ukraine is situated in the central part of Eastern Europe, on the crossroads of major transportation routes from Europe to Asia and from the Scandinavian states to the Mediterranean region).

Dates deployed: October 2019 – April 2020

Job/role while deployed: Staff Officer to the Defense Review Advisory Board in Kiev and later Staff Officer with the Task Force Headquarters.

First impression when arriving “in country”: Central Ukraine had temperate climate and countryside appeared similar to central Alberta. Visible contrast between new and old infrastructure. Modern buildings next to decades old Soviet era apartment buildings.

What are 3 good memories you have from your mission:

- Strong relationship with the people I worked with from Ukraine and other supporting countries

- Lasting friendships with members of my task force that I served with on Operation UNIFIER

- Being involved in the development of democratic institutions and watching a country grow.

Challenges you faced during deployment: Language barrier. The pandemic occurred towards the end of my deployment, resulting in much of the work in Kiev coming to a halt because of the closure to international travel and restrictions on the work place.

How did your deployment help/hurt your civilian employment/studies? My employer was supportive and I was able to return to my position.

What do you remember from when you arrived back in Canada? I was quarantine for two weeks at a CAF air force base before I could return home. This was actually beneficial as it gave me a chance to decompress before returning to civilian life.

Did you face any challenges when you returned from deployment? Being isolated due to the pandemic was difficult. When there was an opportunity to work for the Brigade during the spring and summer, I signed up right away.

Does Remembrance Day feel any different this year being the first one since your return? Last November I took part in a large multi-national ceremony in Kiev. This year, the restrictions on gathering will likely prevent CAF from participating in public.

What should Canadians think about this Remembrance Day? Democracy does not come free. The fight against corruption, autocracy, and apathy continues today.

Corporal (Cpl) Shane R. Kreil, 41 Signals Regiment (2 Sqn)

Cpl Kreil deployed to Latvia

Mission name and country deployed to: Op Reassurance – Latvia (Latvia is in north-eastern Europe with a coastline along the Baltic Sea. It borders with Estonia, Russia, Belarus and Lithuania)

Dates deployed: 10 Jan 2020 – 10 July 2020

Job/role while deployed: Communications Operator in Rear CP and RRB Dets

First impression when arriving “in country”: Latvia is a beautiful – lush green forest covered country – reminds me most of the province of British Columbia with its tall trees and proximity to the Ocean. The people are relatively tall and slender and as a whole, generally friendly. There did seem to be a large number of run-down buildings in less densely populated areas indicative of the Cold War era pre-Latvian independence.

What are 3 good memories you have from your mission:

- The only RRB (Radio Rebroadcast) Exercise that my detachment of 3 soldiers went on was a solid moment for us – a confirmation of skills and faith in our ability to do our job well and independently. The freedom felt at that moment in time wherein we were away from the main battlegroup and left to our own devices was fantastic. It showed us that leadership had confidence in us and proved to ourselves that we could do whatever was required in that role.

- PSP Staff (Civilians hired to run certain tasks around camp) had put on a number of excursions to the surrounding area where we were able to see what Latvia and its culture were all about – one of these was a tour to the KGB museum. It was a fantastic eye-opener that gave us a glimpse into what happened to Latvian citizens during occupation and a feeling as to why they do not want to undergo similar circumstances ever again – hence the integration with NATO. This cultural awareness was a fantastic memory.

- Once again PSP was in the job of creating lasting memories – they hosted a number of Bingo events – these brought a sense of “home” to those deployed in Latvia and helped with bringing nations together – in particular relations with the Spanish who were very boisterous and enthusiastic when it came to Bingo.

What are 3 challenges you faced during deployment:

- COVID 19 was by far the biggest kick for us – I had only JUST begun my mid-tour leave – flew to Dublin, Ireland where I was to spend the next two weeks with family. Very little was out of place the first half day there though there was much talk of closure of certain events. The next day was almost surreal on a guided bus tour – going past the Guinness Factory a few days before St. Patrick’s Day – and it was CLOSED. That was the first indicator we had that this was incredibly serious and impactful – that night as I was on the phone with the family wishing them a safe flight over I got a call telling me I was being recalled to Latvia in the morning – it was heartwrenching calling the family back to tell them NOT to board the plane as I would not be there when they arrived. The next two weeks were spent in quarantine in Latvia and the remainder of the tour felt very different.

- It was difficult to intermingle with NATO personnel at times from other nations due to the difference in spoken languages, both during exercises and during off time. Though this was a challenge it was an excellent opportunity to discover ways to communicate with people whose native language is not English.

- One last major hurdle was not actually in the deployed environment but instead on the home-front. With the world being turned upside down due to Covid 19 in addition to other family matters (deaths, weddings, other personal issues that arose) it was very difficult to be in a virtual bubble in Latvia while the rest of my family had to deal with everything happening in Canada. Due to the remote location we live in there was very little in the way of support services my family could call on to assist which compounded the stresses on both family and me as a deployed member.

How did your deployment help/hurt your civilian employment/studies? Due to deployment I had essentially farmed my job out to a number of other individuals in order to keep things running during the slow season. Unfortunately Covid happened and management decided that restructuring was required – as I was deployed I was unable to compete for any of the positions worked in nor able to provide directional feedback with pros/cons and impacts to business. Upon return to work in July just in time for a busy agricultural season I was promptly demoted and moved into a modified work schedule but with no impact to my pay – just responsibility. Not all for the worse – it means that working from home can be done without concern as to what is actually happening at the branch – major adjustment to way of thinking required is all.

What do you remember from when you arrived back in Canada? It was a late return – plane landed at 2300h in Edmonton – we had to sort baggage and transport all the way to the North end of Edmonton (Garrison) in order to meet personnel that were to transport us to our home unit and from there family would meet us. It also proved difficult communicating to the family as my phone was deactivated during my tour – so messages were being relayed through others. During deployment my Regiment had undergone a leadership change and the new CO/RSM were there to meet us at the garrison – by this time is was about 0200h. After being transported back to Red Deer to meet a very tired looking family it was about 0400h and back in my home town by 0545h. I am still getting used to seeing arrows on grocery store floors and using hand sanitizer with an insane frequency.

Did you face any challenges when you returned from deployment? Minus the work adjustment and getting used to different procedures being used by day to day business challenges upon return have been minimal.

Does Remembrance Day feel any different this year being the first one since your return? Undoubtedly Remembrance Day will be different this year – not only due to many Legions not holding an official ceremony due to Covid fears but a new respect for what our predecessors fought and died for is very real.

What should Canadians think about this Remembrance Day? As Canadians even though we have a diverse history and broad spectrum of personal experiences most of us were born in a free and unoccupied country and cannot fathom a daily struggle for freedom and independence that is happening in other countries around the world even today and has happened in generations past. I would encourage Canadians to really think deeply on what it means to be free and the sacrifices made by many people to keep it this way including time away from families, hardship and difficulty with daily tasks and the ultimate sacrifice when necessary.

Master Bombardier (MBdr) Rhett Quaale 78 Field Battery / 20 Field Regiment

Bdr Quaale deployed to Lebanon

Mission name and country deployed to: Operation Impact Lebanon (Lebanon is located in the Middle East and bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the west, Israel to the south, and Syria to the east and north.

Dates deployed: 14 Dec 2020 – 16 March 2020

Job/role while deployed: Land Border Regt (LBR) Instructor. Our Job was to teach the Lebanese LBRs to work, move and survive in winter conditions. For instance LOSV, Improvised shelters, how to treat cold weather injuries.

First impression when arriving “in country”: It was a bit of a shock to see firsthand how different parts of the country were, from very poor (refugee camps) to very westernized.

What are 3 good memories you have from your mission:

- Improving my own skills for surviving winter conditions

- Making new friends both from Canada and Lebanon

- Getting to see parts of Lebanon that I probably would never see if not for my deployment.

What are 3 challenges you faced during your deployment:

- Language gaps made it difficult to train and trying to convey what we were trying to say through translators

- Working with a fairly new army who aren’t as well equipped as the CAF took some time to get use to

- Being away from friends and family through life events

How did your deployment help/hurt your civilian employment/studies? I am employed full time by the CAF.

What do you remember from when you arrived back in Canada? I remember a sense of disbelief that I was home when I landed in Canada and I was very excited to see my wife and friends again.

Did you face any challenges when you returned from deployment? When I arrived back in Canada it was the beginning of COVID 19 and I had to stay isolated from people I hadn’t seen in months.

Does Remembrance Day feel any different this year being the first one since your return? I’ve always felt pride being a solider but having the opportunity to deploy has made me hold my head a little higher. I’m humbled still by the fact that there are many solders who didn’t make it back home.

What should Canadians think about this Remembrance Day?

Canadians should always remember soldiers stand for Canadian values both domestically and abroad, and that men and woman have died defending our values. As well, soldiers who have come back home with both physical and mental injuries that changed their lives forever. Remember that they went on deployment to represent Canada.

Corporal (Cpl) Courtney McKinley – 41 Signal Regiment, (2 Sqn)

Cpl McKinley deployed to Latvia

Mission name and country deployed to: OP REASSURANCE – Latvia

Dates deployed: 15 JUL 19 – 15 JAN 20

Job/role while deployed: Radio operator – Forward CP

First impression when arriving “in country”: My first impression was being confused by European road signs and lights. A red light flips back to yellow before it turns green! Besides that, wondering why the Latvians did not smile more because their country is beautiful!

What are 3 good memories you have from your mission:

- We did a road move with all the multi-national armoured vehicles through the Latvian countryside. It was nice to see the locals waving and taking photos. The trees in Latvia are the nicest I have seen.

- Another signaller and I went to Latvian elementary schools for Operation Radio Santa where we used our radio’s to “call the North Pole.” I was Santa’s signaller out in the van, who happened to be an old Latvian veteran, while my colleague played the Head Elf in the classrooms. I enjoyed spending a few days away from work to make the kids happy and listen to Santa’s amazing stories.

- Working with soldiers from eight other nations was incredible because we all realized that we are not so different from one another, and that we all share similar experiences being far from home.

What are some challenges you faced during deployment:

- Keeping my focus on my job while also remembering I have people waiting for me at home. It was easier at times for me to ignore things going on in Canada, and I was on exercise for a large part of the tour, which often left me mentally fatigued in my downtime.

- Adjusting how I have been trained to operate to accommodate soldiers from other nations. It is too easy to think the way you have been taught is the best way. Every soldier has something to offer and that is why we all come together as a battlegroup.

How did your deployment help/hurt your civilian employment/studies? When I arrived back in Canada I immediately went back to university. On one hand it is great that I was not too late into the semester — I did not want to be a full year behind. On the other hand, this was a serious change of pace and I struggled tremendously to get back into my post-secondary routine.

What do you remember from when you arrived back in Canada? When the plane first landed in Canada everyone was so ecstatic because we thought we were in Edmonton…turns out we were in Winnipeg with three hours flying left. Eventually we arrived late in the night, it took forever to get our luggage and I had never been so irritable in my life. I just wanted to get home and the delays did not seem to quit. Eventually it all worked out, the logistics of these things are never as simple as imagined while overtired and homesick.

Does Remembrance Day feel any different this year being the first one since your return? Last year I really missed celebrating in Canada, it was not the same. Although all the nations were respectful, Remembrance Day does not carry the same weight for non-Commonwealth countries. This year many people are remaining inside due to the virus, which is great, but you do not see those poppies on jackets as frequently and the ceremonies will be small for safety reasons.

What should Canadians think about this Remembrance Day? The world is quite different than it was last year. With the pandemic and Canadians staying at home, it is easy for people to forget why we celebrate Remembrance Day. Canadians should think of creative ways to show their remembrance to the Fallen. Remembrance Day is a part of Canadian identity that deserves to be preserved and we can do so safely. Wear your poppy during your online conferences/Zoom meetings maybe!

Bombardier (Bdr) Levi Tanner Mee, 78th Field Battery, 20th Field Regiment

Bdr Mee deployed to Latvia

Mission name and country deployed to: Operation Reassurance, Latvia

Dates deployed: 15 August 2019 – 14 October 2019

Job/role while deployed: Command Post Technician / Signaller

First impression when arriving “in country”: First thing I noticed was how old all the buildings and roads where

What are 3 good memories you have from your mission: 1) Visiting downtown Riga. 2) Watching the live fire armoured demonstration. 3) Ball hockey tournament during Latvian Constitution Day.

What are 3 challenges you faced during your deployment: 1) Learning to use new equipment used by the Regular Force. 2) Integrating and communicating with other nations. 3) Finding time to call home due to time zone and work schedule

How did your deployment help/hurt your civilian employment/studies? Really had no effect as I was working for the army doing courses.

What do you remember from when you arrived back in Canada? Being tired from long flight and time change.

Did you face any challenges when you returned from deployment? No, I took leave then returned to working for my unit.

Does Remembrance Day feel any different this year being the first one since your return? No

What should Canadians think about this Remembrance Day? Canadians should be thinking about those who gave their life for their country and those serving overseas now.

Warrant Officer (WO) James Wyszynski 41 Signal Regiment HQ Sqn SSM

WO Wyszynski deployed to Jordan

Mission name and country deployed to: Op IMPACT, CTAT, Jordan, (Jordan is bordered by Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Syria, Israel and Palestine West Bank)

Dates deployed: 07 July 2019 to 12 Jan 2020

Job/role while deployed: CQ Mentor. Imbedded into Infantry Battalion (Bn), 325 Km south of Amman Canadian HQ. 1-15 miles drive north of the ancient city of Aqaba. I Instructed and mentored Jordanian personnel on Logistic Combat Support Services (CSS). This resembles CAF administration company in Infantry Battalion.

I also taught methods of resupply by ground and air transport, convoy drill, counter ambush drill, defensive routine. Spent days with supply, ammunition, rations, medical, vehicle, and weapon spare parts to support an infantry Battalion. Introduced resupply by other methods such as donkey and camel. Aided in instruction of resupply by air and conducted joint exercise with 1 Bn Royal Gurka Regiment (Nepalese under British army)

First impression when arriving “in country”: It was very hot. Temperatures of +42C during the day and +38C at 0445 in morning. The civilian population was were welcoming as was the Jordanian Army.

What are 3 good memories you have from your mission: Each day seeing the beauty of desert land scape and camels wondering freely.

Another highlight was being invited for dinner to a Bedouin camp, where I was guest of honor, was another highlight.

Success of having Jordanian troops depart from hide at night with 37 vehicle convoy, several packets and arrive to destination on time and at correct location.

What are 3 challenges you faced during deployment: I took for granted all students could read and perform basic math. I had to teach these basic skills to them so that they could understand navigation and enable them to be deployable in the field and capable from an operational perspective.

Also, language was always a barrier and I worked closely with a language assistant. We used pictures and drawings to communicate and convey ideas.

How did your deployment help/hurt your civilian employment/studies? This is difficult to assess. The onset of Covid 19 started on my arrival back to Canada. The impact of the virus is well known and I have had very little civilian employment as an independent electrical contractor.

What do you remember from when you arrived back in Canada? That I had not gotten paid my allowance.

Did you face any challenges when you returned from deployment? Civilian Work. This however was due to the pandemic.

Does Remembrance Day feel any different this year being the first one since your return? This was my 6th deployment so it didn’t change anything. Each time I arrive back (from deployment) the county has changed somewhat. Maybe some things like different Canadian currency or store that were open are now closed.

What should Canadians think about this Remembrance Day? I feel grateful that Canada has a strong democratic society, that it is multicultural. Generally Canadian’s take some pride with having strong environmental values. Canada is open, free travel is normal and uninterrupted by the state. Freedom of speech and right to hold peaceful protest are normal. I can’t say 100% for sure that all of these things gains were given to us by our soldiers in conflicts. I do recognize, though, that without their commitment and sacrifice we would be living in very different society.

About 41 Signal Regiment: The Signal Corps in Canada originated in 1903. An independent Reserve Communication Troop was created Red Deer in 1974. As part of the Canadian Armed Forces Communications and Electronics branch, they play a critical role in the communication systems deployed in the field, and increasingly, cyber and intelligence.

About 78th Field Battery: 78th Field Battery is part of the 20th Field Regiment Royal Canadian Artillery, an army reserve unit based out of Red Deer and Edmonton. Created in 1920, it formed part of 13 Field Regiment and saw action in WW II in such places as Boulogne, Calais, The Scheldt, Wortburg, Niemejan, Millimgen.

Lloyd Lewis is Honorary Colonel of 41 Signal Regiment.

Alberta

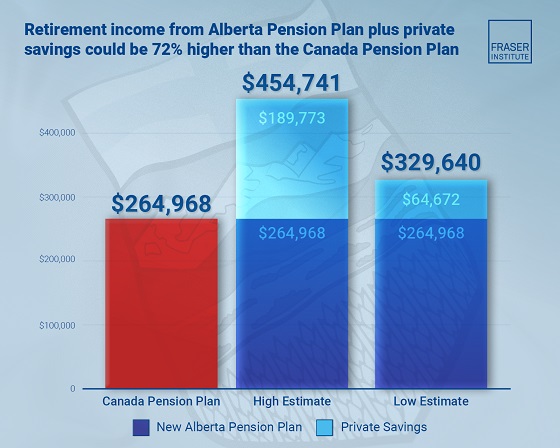

Median workers in Alberta could receive 72% more under Alberta Pension Plan compared to Canada Pension Plan

From the Fraser Institute

By Tegan Hill and Joel Emes

Moving from the CPP to a provincial pension plan would generate savings for Albertans in the form of lower contribution rates (which could be used to increase private retirement savings while receiving the same pension benefits as the CPP under the new provincial pension), finds a new study published today by the Fraser Institute, an independent, non-partisan Canadian public policy think-tank.

“Due to Alberta’s comparatively high rates of employment, higher average incomes, and younger population, Albertans would pay a lower contribution rate through a separate provincial pension plan while receiving the same benefits as under the CPP,” said Tegan Hill, director of Alberta policy at the Fraser Institute and co-author of Illustrating the Potential of an Alberta Pension Plan.

Assuming Albertans invested the savings from moving to a provincial pension plan into a private retirement account, and assuming a contribution rate of 5.85 per cent, workers earning the median income in Alberta ($53,061 in 2025) could accrue a stream of retirement payments totalling $454,741 (pre-tax)—a 71.6 per cent increase from their stream of CPP payments ($264,968).

Put differently, under the CPP, a median worker receives a total of $264,968 in retirement income over their life. If an Alberta worker saved the difference between what they pay now into the CPP and what they would pay into a new provincial plan, the income they would receive in retirement increases. If the contribution rate for the new provincial plan was 5.85 per cent—the lower of the available estimates—the increase in retirement income would total $189,773 (or an increase of 71.6 per cent).

If the contribution rate for a new Alberta pension plan was 8.21 per cent—the higher of the available estimates—a median Alberta worker would still receive an additional $64,672 in retirement income over their life, a marked increase of 24.4 per cent compared to the CPP alone.

Put differently, assuming a contribution rate of 8.21 per cent, Albertan workers earning the median income could accrue a stream of retirement payments totaling $329,640 (pre-tax) under a provincial pension plan—a 24.4 per cent increase from their stream of CPP payments.

“While the full costs and benefits of a provincial pension plan must be considered, its clear that Albertans could benefit from higher retirement payments under a provincial pension plan, compared to the CPP,” Hill said.

Illustrating the Potential of an Alberta Pension Plan

- Due to Alberta’s comparatively high rates of employment, higher average incomes, and younger population, Albertans would pay a lower contribution rate with a separate provincial pension plan, compared with the CPP, while receiving the same benefits as under the CPP.

- Put differently, moving from the CPP to a provincial pension plan would generate savings for Albertans, which could be used to increase private retirement income. This essay assesses the potential savings for Albertans of moving to a provincial pension plan. It also estimates an Albertan’s potential increase in total retirement income, if those savings were invested in a private account.

- Depending on the contribution rate used for an Alberta pension plan (APP), ranging from 5.85 to 8.2 percent, an individual earning the CPP’s yearly maximum pensionable earnings ($71,300 in 2025), would accrue a stream of retirement payments under the total APP (APP plus private retirement savings), yielding a total retirement income of between $429,524 and $584,235. This would be 22.9 to 67.1 percent higher, respectively, than their stream of CPP payments ($349,545).

- An individual earning the median income in Alberta ($53,061 in 2025), would accrue a stream of retirement payments under the total APP (APP plus private retirement savings), yielding a total retirement income of between $329,640 and $454,741, which is between 24.4 percent to 71.6 percent higher, respectively, than their stream of CPP payments ($264,968).

Joel Emes

Alberta

Alberta ban on men in women’s sports doesn’t apply to athletes from other provinces

From LifeSiteNews

Alberta’s Fairness and Safety in Sport Act bans transgender males from women’s sports within the province but cannot regulate out-of-province transgender athletes.

Alberta’s ban on gender-confused males competing in women’s sports will not apply to out-of-province athletes.

In an interview posted July 12 by the Canadian Press, Alberta Tourism and Sport Minister Andrew Boitchenko revealed that Alberta does not have the jurisdiction to regulate out-of-province, gender-confused males from competing against female athletes.

“We don’t have authority to regulate athletes from different jurisdictions,” he said in an interview.

Ministry spokeswoman Vanessa Gomez further explained that while Alberta passed legislation to protect women within their province, outside sporting organizations are bound by federal or international guidelines.

As a result, Albertan female athletes will be spared from competing against men during provincial competition but must face male competitors during inter-provincial events.

In December, Alberta passed the Fairness and Safety in Sport Act to prevent biological men who claim to be women from competing in women’s sports. The legislation will take effect on September 1 and will apply to all school boards, universities, as well as provincial sports organizations.

The move comes after studies have repeatedly revealed what almost everyone already knew was true, namely, that males have a considerable advantage over women in athletics.

Indeed, a recent study published in Sports Medicine found that a year of “transgender” hormone drugs results in “very modest changes” in the inherent strength advantages of men.

Additionally, male athletes competing in women’s sports are known to be violent, especially toward female athletes who oppose their dominance in women’s sports.

Last August, Albertan male powerlifter “Anne” Andres was suspended for six months after a slew of death threats and harassments against his female competitors.

In February, Andres ranted about why men should be able to compete in women’s competitions, calling for “the Ontario lifter” who opposes this, apparently referring to powerlifter April Hutchinson, to “die painfully.”

Interestingly, while Andres was suspended for six months for issuing death threats, Hutchinson was suspended for two years after publicly condemning him for stealing victories from women and then mocking his female competitors on social media. Her suspension was later reduced to a year.

-

Addictions1 day ago

Addictions1 day agoWhy B.C.’s new witnessed dosing guidelines are built to fail

-

Frontier Centre for Public Policy2 days ago

Frontier Centre for Public Policy2 days agoCanada’s New Border Bill Spies On You, Not The Bad Guys

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoCarney Liberals quietly award Pfizer, Moderna nearly $400 million for new COVID shot contracts

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoCarney government should apply lessons from 1990s in spending review

-

Business24 hours ago

Business24 hours agoMark Carney’s Fiscal Fantasy Will Bankrupt Canada

-

Energy2 days ago

Energy2 days agoCNN’s Shock Climate Polling Data Reinforces Trump’s Energy Agenda

-

Opinion1 day ago

Opinion1 day agoCharity Campaigns vs. Charity Donations

-

COVID-1924 hours ago

COVID-1924 hours agoTrump DOJ dismisses charges against doctor who issued fake COVID passports