Agriculture

Canada’s food supply chain is strong but will world-wide pressures effect It?

Within days of government’s shelter in place orders, there were ridiculous scenes of people fighting over toilet paper along with empty shelves in some other areas of grocery stores, including the fresh meat section. It was an eye-opener of what could come. With the food supply chains facing unprecedented pressures caused by Covid-19, governments have been assuring citizens that there are no food shortages and there is no need to hoard or panic buy.

After the weeks of the ongoing Covid-19 disaster there are cracks showing in the world’s ability to keep all of its citizens fed. Overseas there have already been scenes of hungry people looting food trucks. On April 28th, there were street riots in Lebanon over food price increases.

A food truck gets looted by desperate people near Cape Town, South Africa

A healthy food supply chain relies on predictability

In 2015 the Group of 20 (G20), held a conference to address “…food waste and loss – a major global problem…”. It was a much simpler time. The world-wide food supply chain did not have to deal with a very contagious and complicated coronavirus.

When working properly, a country’s food distribution is a marvel of efficiently and logistics. Delivering massive amounts of fresh food to consumers to every corner of the country, every day. But a chain is only as strong as its weakest link.

“It’s something we don’t like doing, no dairy farmer likes doing it. There are just some real limitations in our supply chain right now.” Karlee Conway with Alberta Milk

There are some scenarios happening in North America that have to be an eye-opener for everyone. Food rotting in the fields, whole crops getting ploughed under, fresh milk getting poured down the drain. The milk dumping is also happening in Canada. Karlee Conway with Alberta Milk said that many farmers are forced to make a difficult decision.

“It’s something we don’t like doing, no dairy farmer likes doing it. There are just some real limitations in our supply chain right now.”

And even more shocking, meat and egg producers in North America have already started culling their animals. A lack of buyers and the closing of processing plants due to sickness and even death of employees.

He and she nailed it

Agriculture Minister Devin Dreeshen said this on March 27:

“Alberta does not have a food supply shortage, but the entire national supply chain should be declared an essential service. There are a lot of moving parts to get food to market and onto kitchen tables. Alberta’s supply chain is responding well, but it is not business as usual.”

Many things have changed since then. Elaine Power, a food security expert at Queen’s University, is more blunt, saying the coronavirus pandemic is exposing “critical weaknesses” in various vital networks, including health care systems and food supply chains. “The people who are already food insecure, that’s only going to get worse. The type of resources that people would normally draw on probably aren’t going to be there.”

Beef ready for sale at a grocery store. Will prices go up? Will there be shortages?

Daily press briefing on April 21st

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said in regard to the Cargill beef processing plant closing and another major Alberta plant’s production reduction after staff contracting Covid-19:

“We are not at this point anticipating shortages of beef, but prices might go up. We will of course be monitoring that very, very carefully.”

“We stress the importance of avoiding food losses”

On the same day the Prime Minister talked about the Alberta meat processing plants, the G20’s Agriculture and food ministers held an emergency meeting. The G20 makes up more than 80% of the world’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP). At this virtual meeting, the countries agreed to the following:

“Any emergency measures to contain the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic must not create unnecessary barriers to trade or disruption to global food supply chains.” And that, “Under the current challenging circumstances, we stress the importance of avoiding food losses and waste caused by disruptions throughout food supply chains, which could exacerbate food insecurity and nutrition risks and economic loss.”

Easy to say, much harder to do

Just in North America, if the past 5 weeks alone was a test on the G20’s agreed to statement, an “F” has been earned so far.

Our food system is distributed into two main streams; the large bulk volume packaging going to the food service areas and the smaller personal size portions going to consumer stores.

When the full stop happened, restaurants, hotels, schools and the majority of bulk orders stopped. Regular expedited weekly sales were sent to the grocery stores, leaving massive amount of unsold produce in the fields.

Gene McAvoy photo of a farmer plowing under rip tomato plant fields has upset viewers on Facebook.

Gene McAvoy, associate director of stakeholder relations at the University of Florida’s Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences and president of the NACAA saw the orders stop.

“On March 24th, everything changed, from brokers the orders stopped, everything got quiet. The 25th, (was) super-quiet. Producers were blindsided. Since then tomato (sale) volumes are down 85%, green beans 50%, cabbage is (down about) 50%.”

And it is not just those crop. It’s onions, squash, lettuce and more.

Images of wasted produce and food lines

Without the regular food service industry orders, Florida farmer Paul Allen, in the just first week of April, plowed under more than six million pounds of green beans and cabbages back into his fields. He was far from the only farmer to do this. Allen explains,

“Four million people in the winter season eat lavishly three times a day on cruises from Miami alone. And 120 million tourists per year go to theme parks.”

His sales died up overnight.

Scene of milk dumping in the upstate. made New York Governor to say STOP!

This has lead to hundreds of millions of kilograms and billions of dollars’ worth of life sustaining, nutritious, fresh produce and milk has ended up as rotting waste and dumped down the drain. While, at the same time there were images of thousands of people line up for a food donation.

Countless food banks would gladly take and distribute this lost food. But the food supply system we know is one that is protected, regulated, and inspected. The last few weeks shows that in a world-wide emergency, the system has a few weak links.

On April 27th, after seeing images of milk waste, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo tweeted that he was stepping in to stop the milk dumping, asking that “…dairy producers use the excess milk to make yogurt and cheese that will be distributed to food banks & those in need.”

Helicopter footage from KENS 5 in San Antonio Texas, 10,000 family show up for food.

United Nations warns of famines of ‘biblical proportions’

It’s not just in North America. Problems are showing up around the world. In India, cows are being fed strawberries to get some use out of crops.

The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization has reported the ‘Hammer Blow’ from the corona virus could by the end of 2020, double the amount of people facing actuate food insecurity to 265 million, up from 130 million in 2019. These numbers lead the UN to warn of the possibility of famines of ‘biblical proportions’ across as many as ‘three dozen countries’.

This kind of pending suffering will be hard to stop when the richest and most generous countries in the world are having their own food supply issues, while taking such a massive hit to their economies.

Spring is the start of Alberta’s growing season

In Alberta, the government has already made a plea for workers to fill as many of the 70,000 jobs in the food supply system. Jobs that are usually filled by temporary foreign workers, another program affected by the pandemic. With the planting season upon us, farmers are deciding how much and what to plant in 2020.

Meat production is a major part of Alberta’s economy

Meat production and processing in Alberta is vital to Canada’s supply of food. The three main beef plants in the province, Cargill in High River, JBS Canada in Brooks and Harmony Beef Company in Balzac, have all had Covid-19 problems. While a lot of the final meat processing can and is completed in production facilities and butcher shops across the country, these three main plants are responsible for 75-80% of the federally-inspected slaughter of the cattle for all of Canada.

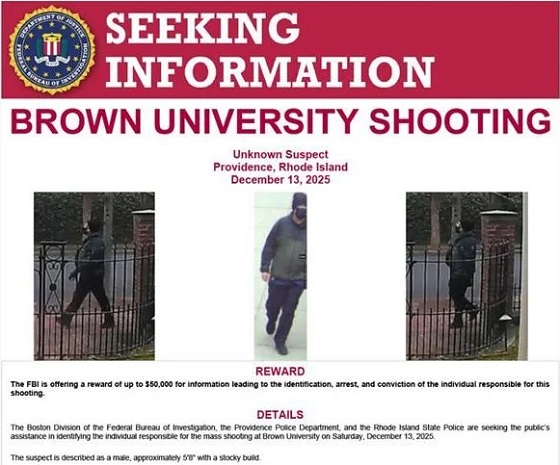

Cargill’s High River plant

Meat processing employees work in close quarters, side-by-side on fast moving assembly lines. With this very contagious virus, it has spread through the workforce. At least 759 workers have tested positive for Covid-19 at the Cargill meat processing plant in High River, which has a workforce of 2,000. There are another 408+ people in the community that have tested positive for Covid-19, making this the largest outbreak linked to a single site in Canada. The Cargill plant is now temporarily closed.

At least 276 workers have also tested positive for Covid-19 at the JBS Food Canada beef processing plant in Brooks, with the community itself having over 760 cases. The plant is now down to one shift.

While Alberta and the Canadian governments work together to increase the number of meat inspectors available, Fabian Murphy, president of the Agriculture Union that represents the federal meat inspectors wants safety guarantees. Seven inspectors have already tested positive for the virus at the Cargill plant. Murphy has also stated that it’s only a matter of time before JBS plant in Brooks is also forced to temporarily halt production, stating that a, “14-day shutdown would allow all employees to self-isolate. After (that) production at the facility could resume.”

Pork producers are also under great pressures

The Canadian pork industry across western Canada is under extreme pressure, being called “the worst scenario seen in decades.” Faced with dropping prices for their finished hogs, no buyers for their piglets for finishing and growing backlogs in processing, the concern now is how many family pork farms will go under before this is over?

Production lines in Western Canada plants have been slowed down for better safety for workers. Add to that, US pork processing plants closing because of widespread Covid-19 outbreaks with their workers. Currently there has been a 25% reduction in pork slaughter capacity south of the border. Both the Canadian and the US pork industry producer have warned of large amounts of animals will have to be culled. And it has already started in small scales with larger culls within the next weeks.

Chicken producers are facing the same issues

Chicken producers are also facing the same issues. Sofina Foods Inc., that runs a Lilydale chicken processing plant in Calgary confirmed that one employee tested positive for COVID-19 and is in self-isolation. As well, doctors are investigating two possible cases of COVID-19 found in workers at Mountain View Poultry, near the Town of Okotoks.

British Columbia has at least two chicken processing plants with confirmed growing Covid-19 cases. One plant has temporary closed.

The talk of major animal culls, is not just talk

John Tyson, chairman of Tyson Foods, the world’s second largest processor and marketer of chicken, beef, and pork had very strong comments in a full-page ad published in The New York Times, Washington Post and Arkansas Democrat-Gazette. In part Tyson’s top person said bluntly:

“The food supply chain is breaking. Meat processing plants across the US are closing due to the pandemic. US farmers don’t have anywhere to sell their livestock. Millions of pigs, chickens and cattle will be euthanized because of slaughterhouse closures, limiting supplies at grocers.”

With published reports, the animal culling has already began. One Prince Edward Island farm euthanized market ready hogs and then dumped them in a landfill. Iowa farmer, Al Van Beek said, “What are we going to do?” after ordering 7,500 piglets to be aborted. Daybreak Foods Inc., based in Lake Mills, Wisconsin has used carts and tanks of carbon dioxide to euthanize tens of thousands of healthy egg-laying hens. Eggs are no longer being bought by their customers in the restaurants and food-service business.

USDA sets up “Coordination Centre” to “assist on depopulation”

The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) has posted online:

“The USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) is establishing a National Incident Coordination Center to provide direct support to producers whose animals cannot move to market as a result of processing plant closures due to COVID-19. Going forward, APHIS Coordination Center, State Veterinarians, and other state officials will be assisting to help identify potential alternative markets if a producer is unable to move animals, and if necessary, advise and assist on depopulation and disposal methods.”

“We stress the importance of avoiding food losses and waste caused by disruptions throughout food supply chains, which could exacerbate food insecurity and nutrition risks and economic loss.” April 21st G20 agreement.

If the G20 matters, North America, gets an “F” so far

The stress on the food supply chain continues to grow the longer Covid-19 lasts. On April 28th Meat producer JBS said it was reopening a Minnesota pork plant, that was shuttered by the pandemic to euthanize up to 13,000 pigs a day for farmers, not to produce meat for consumers.

Governments must get a handle on the cull of livestock and the billions of dollars of rotting produce meant to go to our populations. There are thousands of people that are hungry. The use of Food Banks in North America has hit new records, with more people needing help every day. But at the same time billions of dollars of food is being destroyed.

What’s wrong with the picture? It is just wrong; the USDA has set-up a Coordination Center to help farmer either sell their products or help kill and dispose of the carcasses in mass. All this, while people go hungry in the same country during a pandemic.

Governments need to step in and redirect this food from a landfill to population that needs it. Until this happens, the links in our food supply chain will continue to be stressed. Food for thought.

A farm tractor is silhouetted against a setting sun near Mossbank, Saskatchewan, Saturday May 11, 2002. (THE CANADIAN PRESS / Adrian Wyld)

PANDAMNIT! Alberta cancels festivals & gatherings over 15 people till September

Agriculture

End Supply Management—For the Sake of Canadian Consumers

This is a special preview article from the:

U.S. President Donald Trump’s trade policy is often chaotic and punitive. But on one point, he is right: Canada’s agricultural supply management system has to go. Not because it is unfair to the United States, though it clearly is, but because it punishes Canadians. Supply management is a government-enforced price-fixing scheme that limits consumer choice, inflates grocery bills, wastes food, and shields a small, politically powerful group of producers from competition—at the direct expense of millions of households.

And yet Ottawa continues to support this socialist shakedown. Last week, Prime Minister Mark Carney told reporters supply management was “not on the table” in negotiations for a renewed United States-Mexico-Canada Trade Agreement, despite U.S. negotiators citing it as a roadblock to a new deal.

Supply management relies on a web of production quotas, fixed farmgate prices, strict import limits, and punitive tariffs that can approach 300 percent. Bureaucrats decide how much milk, chicken, eggs, and poultry Canadians farmers produce and which farmers can produce how much. When officials misjudge demand—as they recently did with chicken and eggs—farmers are legally barred from responding. The result is predictable: shortages, soaring prices, and frustrated consumers staring at emptier shelves and higher bills.

This is not a theoretical problem. Canada’s most recent chicken production cycle, ending in May 2025, produced one of the worst supply shortfalls in decades. Demand rose unexpectedly, but quotas froze supply in place. Canadian farmers could not increase production. Instead, consumers paid more for scarce domestic poultry while last-minute imports filled the gap at premium prices. Eggs followed a similar pattern, with shortages triggering a convoluted “allocation” system that opened the door to massive foreign imports rather than empowering Canadian farmers to respond.

Over a century of global experience has shown that central economic planning fails. Governments are simply not good at “matching” supply with demand. There is no reason to believe Ottawa’s attempts to manage a handful of food categories should fare any better. And yet supply management persists, even as its costs mount.

Those costs fall squarely on consumers. According to a Fraser Institute estimate, supply management adds roughly $375 a year to the average Canadian household’s grocery bill. Because lower-income families spend a much higher proportion of their income on food, the burden falls most heavily on them.

The system also strangles consumer choice. European countries produce thousands of varieties of high-quality cheeses at prices far below what Canadians pay for largely industrial domestic products. But our import quotas are tiny, and anything above them is hit with tariffs exceeding 245 percent. As a result, imported cheeses can cost $60 per kilogram or more in Canadian grocery stores. In Switzerland, one of the world’s most eye-poppingly expensive countries, where a thimble-sized coffee will set you back $9, premium cheeses are barely half the price you’ll find at Loblaw or Safeway.

Canada’s supply-managed farmers defend their monopoly by insisting it provides a “fair return” for famers, guarantees Canadians have access to “homegrown food” and assures the “right amount of food is produced to meet Canadian needs.” Is there a shred of evidence Canadians are being denied the “right amount” of bread, tuna, asparagus or applesauce? Of course not; the market readily supplies all these and many thousands of other non-supply-managed foods.

Like all price-fixing systems, Canada’s supply management provides only the illusion of stability and security. We’ve seen above what happens when production falls short. But perversely, if a farmer manages to get more milk out of his cows than his quota, there’s no reward: the excess must be

dumped. Last year alone, enough milk was discarded to feed 4.2 million people.

Over time, supply management has become less about farming and more about quota ownership. Artificial scarcity has turned quotas into highly valuable assets, locking out young farmers and rewarding incumbents.

Why does such a dysfunctional system persist? The answer is politics. Supply management is of outsized importance in Quebec, where producers hold a disproportionate share of quotas and are numerous enough to swing election results in key ridings. Federal parties of all stripes have learned the cost of crossing this lobby. That political cowardice now collides with reality. The USMCA is heading toward mandatory renegotiation, and supply management is squarely in Washington’s sights. Canada depends on tariff-free access to the U.S. market for hundreds of billions of dollars in exports. Trading away a deeply-flawed system to secure that access would make economic sense.

Instead, Ottawa has doubled down. Not just with Carney’s remarks last week but with Bill C-202, which makes it illegal for Canadian ministers to reduce tariffs or expand quotas on supply-managed goods in future trade talks. Formally signalling that Canada’s negotiating position is hostage to a tiny domestic lobby group is reckless, and weakens Canada’s hand before talks even begin.

Food prices continue to rise faster than inflation. Forecasts suggest the average family will spend $1,000 more on groceries next year alone. Supply management is not the only cause, but it remains a major one. Ending it would lower prices, expand choice, reduce waste, and reward entrepreneurial farmers willing to compete.

If Donald Trump can succeed in forcing supply management onto the negotiating table, he will be doing Canadian consumers—and Canadian agriculture—a favour our own political class has long refused to deliver.

The original, full-length version of this article was recently published in C2C Journal. Gwyn Morgan is a retired business leader who was a director of five global corporations.

Agriculture

Supply Management Is Making Your Christmas Dinner More Expensive

From the Frontier Centre for Public Policy

By Conrad Eder

The food may be festive, but the price tag isn’t, and supply management is to blame

With Christmas around the corner, Canadians will be heading to the grocery store to pick up the essentials for a tasty Christmas feast. Milk and eggs to make dinner rolls, butter for creamy mashed potatoes, an assortment of cheeses as an appetizer, and, of course, the Christmas turkey.

All delicious. All essential. And all more expensive than they need to be because of a longstanding government policy. It’s called supply management.

Consider what a family might purchase when hosting Christmas dinner. Two cartons of eggs, two cartons of milk, a couple of blocks of cheese, a few sticks of butter, and an eight-kilogram turkey. According to Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada and Statistics Canada, that basket of goods costs a little less than $80.

Using price premiums calculated in a 2015 University of Manitoba study, Canada’s supply management system is responsible for $16.69 to $20.48 of the cost of that Christmas dinner. That’s a 21 to 26 per cent premium Canadian consumers pay on those five staples alone. Planning on making a yogurt dip or serving ice cream with dessert? Those extra costs continue to climb.

Canadians pay these premiums for poultry, dairy and eggs because of how Canada’s supply management system works. Farmers must obtain government-issued production quotas that dictate how much they’re allowed to produce. Prices are set by government bodies rather than in an open market. High tariffs block imports and restrict competition from international producers.

The costs of supply management are significant, amounting to billions of dollars every year, yet they are largely hidden, spread across millions of households’ grocery bills. Meanwhile, the benefits flow to a small number of quota-holding farmers. Their quotas are worth millions of dollars and help ensure profitable returns.

These farmers have every incentive to lobby, organize and defend the current system. Wanting special protection is one thing. Actually being given it is another. It is the responsibility of elected officials to resist such demands. Elected to represent all Canadians, politicians should unapologetically prioritize the public interest over any special interests.

Yet in June 2025, Parliament did the opposite. Rather than solve a problem that costs Canadians billions each year, members of Parliament from every party, Liberal, Conservative, Bloc, NDP and Green, unanimously approved Bill C-202, further entrenching the system that makes grocery bills more expensive at a time when families can least afford it. Bill C-202 prohibits Canada from offering any further market access concessions on supply-managed sectors in future trade negotiations.

This decision is even more disappointing when we consider what other nations have already accomplished. Australia and New Zealand demonstrate that removing supply management is not only possible but beneficial.

Australia operated a dairy quota system for decades before abolishing it in 2000. New Zealand began dismantling its dairy supply management regime in 1984 and completed the process in 2001. Both countries found that competitive markets provided their citizens with the access to goods they needed without the hidden costs. If these countries could eliminate supply management, so can Canada.

As the government scrambles to combat the rising cost of living, one of the simplest and most effective solutions continues to be ignored. Eliminating supply management. Removing the quotas, the price controls and the tariffs would allow market competition to do what it does across every other product category. It delivers choice, quality and affordability.

As Canadians gather for Christmas dinner, the feast may be delicious, but it will once again be more expensive than it needs to be. That is the cost of supply management, and Canadians should no longer have to bear it.

Conrad Eder is a policy analyst at the Frontier Centre for Public Policy.

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoThere’s No Bias at CBC News, You Say? Well, OK…

-

Uncategorized1 day ago

Uncategorized1 day agoMortgaging Canada’s energy future — the hidden costs of the Carney-Smith pipeline deal

-

International1 day ago

International1 day agoAustralian PM booed at Bondi vigil as crowd screams “shame!”

-

Opinion2 days ago

Opinion2 days agoReligion on trial: what could happen if Canada passes its new hate speech legislation

-

Automotive24 hours ago

Automotive24 hours agoCanada’s EV gamble is starting to backfire

-

Agriculture21 hours ago

Agriculture21 hours agoEnd Supply Management—For the Sake of Canadian Consumers

-

Alberta20 hours ago

Alberta20 hours agoAlberta Next Panel calls to reform how Canada works

-

Environment18 hours ago

Environment18 hours agoCanada’s river water quality strong overall although some localized issues persist