Community

Armistice Day 11/11/1918 from a Red Deer perspective in pictures and story

Armistice Day 1918

One hundred and two years ago, at the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month (i.e. November 11, 1918), the horrific First World War finally came to an end. It was one of the most momentous events in history.

The outbreak of the War in August 1914 had been greeted with patriotic excitement. Eager young men flocked to the Red Deer Armouries to enlist. Many felt that if they did not join up as soon as possible, they would miss the “big show” before it was over by Christmas. (Click on any image to enlarge it and open gallery).

Before long, however, the reality of modern war began to set in. The Canadians saw their first major action at St. Julien in April 1915. This great battle involved the first mass use of poison gas as a weapon on the Western Front. The Canadians won high honours for their bravery and tenacity in the horrendous conditions. Nevertheless, the casualty rate was staggering, including many from Central Alberta.

The summer and fall of 1916 brought the epic Battle of the Somme. The first day’s assault brought 57,470 casualties for the British forces (still the worst one day loss of life in the history of the British Army). When the battle finally ended in November 1916, there were more than one million casualties. Nearly 50 young men from Red Deer and area lost their lives and roughly three times that number were wounded. Tragically, the stalemate along the Front continued.

1917 brought some great victories for the Canadian Corps. The best remembered is the Battle of Vimy Ridge in April. However, that triumph came with a great cost. 12 young men from Red Deer and area lost their lives in the first day’s assault and another 16 were killed during the rest of the battle.

That victory was followed by Hill 70. While that battle once again demonstrated Canadian skill and valour, more than 40 from Central Alberta became casualties.

Passchendaele was technically a victory, but the losses of life were so horrendous and the gains so limited that it is hard to consider it as such. The Canadians suffered 16,000 casualties through an incredible sea of mud to move the line less than 9 ½ km. Sir Winston Churchill later summed up the battle as “a forlorn expenditure of valour and life without equal in futility”.

In the spring of 1918, the Germans launched a huge, and initially successful, grand offensive. However, by summer, it had faltered. The Western Front ground into another stalemate.

Then on August 8, 1918, the Allied High Command launched a major offensive with the Canadians as one of the key units in the great assault. The successes by the Canadian Corps at the French city of Amiens were truly impressive. A huge hole was punched through the German defences.

German morale was permanently shattered. German General Eric Ludendorff described the commencement of the Battle of Amiens as the “black day of the German Army in the history of the War”.

The great Allied victory turned out to be the first of a string of major successes, collectively known as The 100 Days. The German armies were soon rapidly falling back from their frontal positions in Northern France and Belgium. The Canadians, as some of the very best assault troops in the Allied forces, often led the push forwards.

On September 27, 1918, the Battles of Canal du Nord and Cambrai commenced. By the time that the City of Cambrai was captured in October, the Canadians had scored one of the most impressive tactical victories of the War.

Once again, the costs had been enormous. From August to October 11, 1918, more than 40,000 Canadians had either been killed or wounded (20% of the total Canadian losses of the War).

Hence, the community greeted the pending news of the end of the War with as much of a sense of relief as one of rejoicing. Nearly 120 local young men had lost their lives. A great many others suffered wounds to their bodies and their minds. The terrible toll of the war was amplified by the fact that several of the returning veterans were bringing home a new scourge, the Spanish Influenza.

In early November, the Canadians were advancing towards the Belgian city of Mons, where the fighting for the British forces had commenced in August 1914. It was a highly symbolic objective.

On November 7, the local C.P.R. employees were given a half-day holiday on the rumour that a cease-fire agreement had already been signed. On November 8, one of the local weekly newspapers printed two editions in order to keep up with the rapid succession of announcements and rumours.

On Monday, November 11 at 1:30 a.m., word was received that all hostilities would cease on all fronts at 11 a.m., London time. Just as the fighting came to an end, the Canadians captured Mons. Thus, the Great War ended where it had begun.

The local papers quickly printed a special issue with the news. Mayor G. W. Smith declared a half-day public holiday. Plans were also quickly made for a civic celebration despite the Board of Health’s injunction against any public gatherings.

At 12:30 p.m., all the bells and whistles in the city broke out in a thirty- minute peal of rejoicing. Patriotic songs were played on a special calliope that had been set up at the Western General Electric steam plant.

A crowd of returned veterans, local dignitaries and ordinary citizens paraded through the streets with the Red Deer Community Band and the local Fire Brigade taking the lead. The throngs then gathered in what is now City Hall Park for a ceremony of celebration and thanksgiving.

There were numerous speeches and choruses of songs. Helen Moore Dawe and Ruth Locke led the crowd in the singing. A gramophone was used to broadcast a special address by Sir Thomas White, the federal Minister of Finance. Mayor G.W. Smith asserted in his speech that this was “the most important day in history since the death of Jesus Christ”.

In the evening, there was a huge bonfire on the City Square accompanied by the shooting of fireworks. City Council also treated a large number of veterans to a special civic banquet.

Tragically, the joys over the end of the War were quickly dampened by a renewed outbreak of the flu caused by the large public gatherings. By the time that the great pandemic abated towards the end of the year, the flu claimed 54 lives locally.

Nevertheless, people fervently prayed that they had just witnessed the end of “The War to End All Wars”.

Michael Dawe

This article was updated from it’s original publication date of November 11, 2018.

Community

Support local healthcare while winning amazing prizes!

|

|

|

|

|

|

Community

SPARC Caring Adult Nominations now open!

Check out this powerful video, “Be a Mr. Jensen,” shared by Andy Jacks. It highlights the impact of seeing youth as solutions, not problems. Mr. Jensen’s patience and focus on strengths gave this child hope and success.

👉 Be a Mr. Jensen: https://buff.ly/8Z9dOxf

Do you know a Mr. Jensen? Nominate a caring adult in your child’s life who embodies the spirit of Mr. Jensen. Whether it’s a coach, teacher, mentor, or someone special, share how they contribute to youth development. 👉 Nominate Here: https://buff.ly/tJsuJej

Nominate someone who makes a positive impact in the live s of children and youth. Every child has a gift – let’s celebrate the caring adults who help them shine! SPARC Red Deer will recognize the first 50 nominees. 💖🎉 #CaringAdults #BeAMrJensen #SeePotentialNotProblems #SPARCRedDeer

s of children and youth. Every child has a gift – let’s celebrate the caring adults who help them shine! SPARC Red Deer will recognize the first 50 nominees. 💖🎉 #CaringAdults #BeAMrJensen #SeePotentialNotProblems #SPARCRedDeer

-

Indigenous2 days ago

Indigenous2 days agoInternal emails show Canadian gov’t doubted ‘mass graves’ narrative but went along with it

-

Bruce Dowbiggin2 days ago

Bruce Dowbiggin2 days agoEau Canada! Join Us In An Inclusive New National Anthem

-

Crime2 days ago

Crime2 days agoEyebrows Raise as Karoline Leavitt Answers Tough Questions About Epstein

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoCarney’s new agenda faces old Canadian problems

-

Alberta2 days ago

Alberta2 days agoCOWBOY UP! Pierre Poilievre Promises to Fight for Oil and Gas, a Stronger Military and the Interests of Western Canada

-

Alberta2 days ago

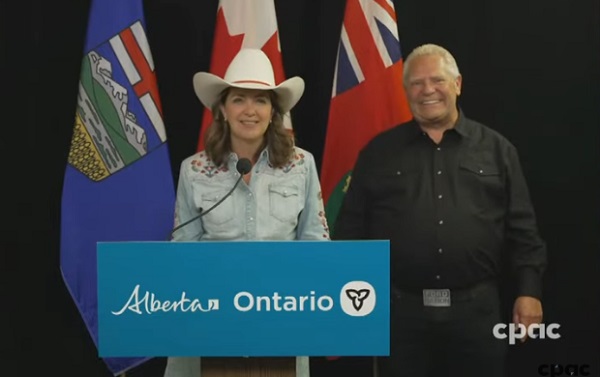

Alberta2 days agoAlberta and Ontario sign agreements to drive oil and gas pipelines, energy corridors, and repeal investment blocking federal policies

-

Crime1 day ago

Crime1 day ago“This is a total fucking disaster”

-

International2 days ago

International2 days agoChicago suburb purchases childhood home of Pope Leo XIV