Economy

Former socialist economist explains why central planning never works

From the Fraser Institute

Central planning from the inside—an interview with a Soviet-era economist

In our descriptions of socialism in Poland and Estonia, we often quoted firsthand accounts of Poles and Estonians who lived through the period. These were workers, consumers, victims of oppression and resistance fighters. One voice that we didn’t capture was that of the planner—the government official charged with making the economy work, despite socialism’s enormous handicaps.

To better understand that perspective, I recently interviewed Gia Jandieri, an economist who worked for the State Supply Committee in Georgia from 1984 to 1989.

In 1989 Gia cofounded the very first non-governmental organization in Soviet Georgia (the Association of Young Economists) to push for market economic education. And in 2001 he established a think-tank, the New Economic School, to promote economic freedom. The New Economic School has been a full member of the Economic Freedom Network since 2004.

Here’s our discussion (lightly edited for readability):

Matthew Mitchell (MM):

How did you become an economist and a Soviet planner?

Gia Jandieri (GM):

It was accidental. In 1984 my mother worked at the Gossnab (the State Supply Committee for the Central Planning Authority) and she offered to introduce me to her boss. At that time I was only 23 years old and had graduated from the Georgian Polytechnical Institute. My knowledge of economics was mostly from life and family experience (my parents worked at a metallurgical plant).

But as a student in 1979 I had had what I thought were a few strange discussions with a teacher of political economy. Like most teachers, he was no true believer in socialism (it was hard for anyone to believe at that time). But he was required to teach the propaganda. What surprised me was that he was willing to publicly agree with me about my suspicions that the system was failing and might even collapse. This was rare, and he was taking a risk. But it also inspired me. It is also important to note that he wanted to hide his hesitation about Marxism and the Soviet system and he also wanted me to stop my questions, and/or stop attending his lectures (which was of course not allowed). I recall he told me: “either I report you or someone reports both of us for having prohibited discussions.”

When I finished my university study of engineering, I was already sure I wanted to be an economist. So, when the opportunity arose in 1984 to work at the State Supply Committee, I seized it.

MM:

Tell us a little bit about the job of a planner. What were your responsibilities? And how did you go about doing them?

GJ:

Our department inside of Gossnab was responsible for monitoring the execution of agreements for production of goods and government orders. My task was to verify that the plans had been executed correctly, to find failures and problems, and to report to the higher authorities.

This included reading lots of reports and visiting the factories and their warehouses for auditing.

The Soviet economy had been in a troublesome condition since the 1970s. We (at the Gossnab) had plenty of information about failures, but it wasn’t useful. We knew that the quality of produced goods was very low, that any household good that was of usable quality was in deficit, and that the shortages encouraged people to buy on the black market through bribes.

In reality, a bribe was a substitute for a market-determined price; people were interested in paying more than the official price for the goods they valued, and the bribe was a way for them to indicate that they valued it more than others.

The process of planning was long. The government had to study demand, find resources and production capacities, create long-run production and supply plans, compare these to political priorities, and get approval for general plans at the Communist Party meetings. Then the general plans needed to be converted to practical production and supply plans, with figures about resources, finances, material and labour, particular producers, particular suppliers, transportation capacities, etc. After this, we began the process of connecting factories and suppliers to one another, organizing transportation, arranging warehousing, and lining up retail shops.

The final stage of the planning process was to send the participating parties their own particular plans and supply contracts. These were obligatory government orders. Those who refused to follow them or failed to fulfill them properly were punished. The production factories had no right or resources to produce any other goods or services than those described in the supply contracts and production plans they received from the authorities. Funny enough, though, government officials could demand that they produce more goods than what was indicated in the plans.

MM:

What made your job difficult? Let’s assume that a socialist planner is 100 per cent committed to the cause; all he or she wants to do is serve the state and the people. What makes it difficult to do that?

GJ:

There were several difficulties. We had to find appropriate consumer data and compare it to the data of suppliers (of production goods mostly). I was working with several (5-15) factories per year. I needed to have current and immediate information, but the state companies were always trying to hide or falsify their reports. In some cases, waste and theft could be so significant that production had to be halted.

The planners invested vast sums of money and time in data collection and each had special units of data processing.

This was a technical exercise and had nothing to do with efficiency or usefulness. The collected data was outdated by the time it was printed. The planning, approval, and execution processes could take many years to complete, and by the time plans were ready, demand had usually changed, creating deficits of what was demanded and surpluses of what was not demanded. The planners, no matter how dedicated or intelligent they might be, simply couldn’t meet the demands of the customers.

Central planning was not an easy exercise. The central planners needed to understand what was needed—both production supplies and consumer goods. But, of course, we had no way of knowing what people truly wanted because there was no market. Consumers weren’t free to choose from different suppliers and new suppliers weren’t free to enter the market to offer new or slightly different goods.

One of the more helpful ways to find out what people wanted was to look at what consumers in the West wanted since they actually had economic freedom and their demands were quickly satisfied. The government also did a lot of industrial spying to steal Western production ways and technologies.

MM:

Were most of the planners you encountered 100 per cent committed to the cause? Were they incentivized to serve the cause?

GJ:

Some of the staffers were dedicated to their work. Others were mostly thinking about how they could obtain bribes from the production factories as a reward for closing their eyes to mismanagement and failure. The planners were also involved in more significant corruption to allow the production factories to have extra materials and financial resources so they could produce for the black market or so they could simply steal.

Then the revenue from these bribes would be divided among all personnel from different agencies (like the Price Committee, Auditing (“Public Control”), and several other agencies charged with inspections). So, in fact, the system generated corruption as a substitute for official incentives. If anything was still operating, this was mostly due to these corrupt incentives and not in spite of them.

The planning system was quite complex and involved many governmental offices though the main decisions were made by the Communist Party. Planning authorities would report to the Party leadership what they thought would be possible to produce and Party leaders would inevitably demand higher quantities.

Gosplan was bureaucratic to its core, both in principle and character. Nobody was allowed to innovate other than planned/artificial innovation. Everyone had to work only by decrees and orders coming from the political leadership. The political orders and bribes were the only engines that were moving anything. Market incentives didn’t exist. Bonuses (premia) were awarded according to bureaucratic rules, and, paradoxically, these destroyed the motivation of the genuinely hard workers.

MM:

Moving beyond economics a bit, how did the socialist system affect other aspects of life? Culture, families, relationships, civil institutions?

GJ:

One of the examples is Western pop-music. Soviet propaganda tried to hide Western culture. Music schools mostly taught Russian classical music and some folk music of various Soviet ethnic nationalities, but it was mostly Russian.

Jazz and hard rock were not prohibited but very much limited. That of course encouraged smuggling and illegal dissemination, as in every sector. Soviet music factories were buying some rights to the music (for instance the Beatles, Louis Armstrong and Ella Fitzgerald). But these recordings were only available in limited quantities and were of bad quality in order to limit their influence.

Small illegal outfits would make unofficial and illegal copies of any popular western music (not classical).

Cultural institutions like theatre or cinema were harshly censored and mostly served the propaganda machine. The people involved in these sectors did what all producers of goods did. They needed to lobby their benefactors in the bureaucracy, bribing and currying favour with them in different ways. It was said that only one out of four films produced would be shown in the cinemas. The other three films were only produced so studios could steal the resources and obtain higher reimbursements.

Before Soviet rule, Georgia was a property rights and ethics-based society. We have ancient proverbs that testify to this. The Soviets killed the ethical leaders, the property-owning elite, and confiscated their property. The stolen property was supposed to be held in common. In fact, the bureaucracy took it.

State ownership of property opened the way to waste and theft of construction and production materials, office inventory, fertilizer, harvested agricultural products, etc.

In Georgia, one bright spot was underground education. Georgians succeeded in growing a network of informal tutors who effectively operated despite very harsh efforts by the authorities to quash them. These skillful teachers prepared the young people for university exams. This was so widespread that some successful young people (including my wife and friends, for instance) started offering private (completely illegal) teaching services when they were university students.

MM:

To this day, socialism remains alluring to many in the West, especially young people. What do you have to say to the 46 per cent of Canadians aged 18-34 who support socialism?

GJ:

Very simply, it is a mistake to think socialism fails because of the wrong managers. This mistake allows people to think that it’ll work the next time it is tried, if we just have better people. In fact the opposite is true—socialism invites the wrong managers. It doesn’t reward a great manager who tries to improve the system but a person who can adapt to and accept the corruption, waste and theft. Socialism also encourages corruption. When more resources are in the control of politicians and the bureaucracy, there is more favouritism, privilege, and discrimination. Jobs and business opportunities are based on privilege rather than market competition. This means naïve people will always be cheated by brazen liars and manipulators.

Poor people are told that the state is under their control but in fact the bureaucracy and political hierarchy control everything.

In socialism, nature and natural resources are abused and wasted. The Tragedy of the Commons runs rampant without private property, voluntary cooperation, and ethics. The government tries to manage everything centrally and totally fails because it lacks dynamic information, competitive discipline, and proper incentives.

Business

Canada’s loyalty to globalism is bleeding our economy dry

This article supplied by Troy Media.

Trump’s controversial trade policies are delivering results. Canada keeps playing by global rules and losing

U.S. President Donald Trump’s brash trade agenda, though widely condemned, is delivering short-term economic results for the U.S. It’s also revealing the high cost of Canada’s blind loyalty to globalism.

While our leaders scold Trump and posture on the world stage, our economy is faltering, especially in sectors like food and farming, which have been sacrificed to international agendas that don’t serve Canadian interests.

The uncomfortable truth is that Trump’s unapologetic nationalism is working. Canada needs to take note.

Despite near-universal criticism, the U.S. economy is outperforming expectations. The Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta projects 3.8 per cent second-quarter GDP growth.

Inflation remains tame, job creation is ahead of forecasts, and the trade deficit is shrinking fast, cut nearly in half. These results suggest that, at least in the short term, Trump’s economic nationalism is doing more than just stirring headlines.

Canada, by contrast, is slipping behind. The economy is contracting, manufacturing is under pressure from shifting U.S. trade priorities, and food

inflation is running higher than general inflation. One of our most essential sectors—agriculture and food production—is being squeezed by rising costs, policy burdens and vanishing market access. The contrast with the U.S. is striking and damning.

Worse, Canada had been pushed to the periphery. The Trump administration had paused trade negotiations with Ottawa over Canada’s proposed digital services tax. Talks have since resumed after Ottawa backed away from implementing it, but the episode underscored how little strategic value

Washington currently places on its relationship with Canada, especially under a Carney-led government more focused on courting Europe than securing stable access to our largest export market. But Europe, with its own protectionist agricultural policies and slower growth, is no substitute for the scale and proximity of the U.S. market. This drift has real consequences, particularly for

Canadian farmers and food producers.

The problem isn’t a trade war; it’s a global realignment. And while Canada clings to old assumptions, Trump is redrawing the map. He’s pulling back from institutions like the World Health Organization, threatening to sever ties with NATO, and defunding UN agencies like the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the global body responsible for coordinating efforts to improve food security and support agricultural development worldwide. The message is blunt: global institutions will no longer enjoy U.S. support without measurable benefit.

To some, this sounds reckless. But it’s forcing accountability. A senior FAO official recently admitted that donors are now asking hard questions: why fund these agencies at all? What do they deliver at home? That scrutiny is spreading. Countries are quietly realigning their own policies in response, reconsidering the cost-benefit of multilateralism. It’s a shift long in the making and long resisted in Canada.

Nowhere is this resistance more damaging than in agriculture. Canada’s food producers have become casualties of global climate symbolism. The carbon tax, pushed in the name of international leadership, penalizes food producers for feeding people. Policies that should support the food and farming sector instead frame it as a problem. This is globalism at work: a one-size-fits-all policy that punishes the local for the sake of the international.

Trump’s rhetoric may be provocative, but his core point stands: national interest matters. Countries have different economic structures, priorities and vulnerabilities.

Pretending that a uniform global policy can serve them all equally is not just naïve, it’s harmful. America First may grate on Canadian ears, but it reflects a reality: effective policy begins at home.

Canada doesn’t need to mimic Trump. But we do need to wake up. The globalist consensus we’ve followed for decades is eroding. Multilateralism is no longer a guarantee of prosperity, especially for sectors like food and farming. We must stop anchoring ourselves to frameworks we can’t influence and start defining what works for Canadians: secure trade access, competitive food production, and policy that recognizes agriculture not as a liability but as a national asset.

If this moment of disruption spurs us to rethink how we balance international cooperation with domestic priorities, we’ll emerge stronger. But if we continue down our current path, governed by symbolism, not strategy, we’ll have no one to blame for our decline but ourselves.

Dr. Sylvain Charlebois is a Canadian professor and researcher in food distribution and policy. He is senior director of the Agri-Food Analytics Lab at Dalhousie University and co-host of The Food Professor Podcast. He is frequently cited in the media for his insights on food prices, agricultural trends, and the global food supply chain

Troy Media empowers Canadian community news outlets by providing independent, insightful analysis and commentary. Our mission is to support local media in helping Canadians stay informed and engaged by delivering reliable content that strengthens community connections and deepens understanding across the country

Business

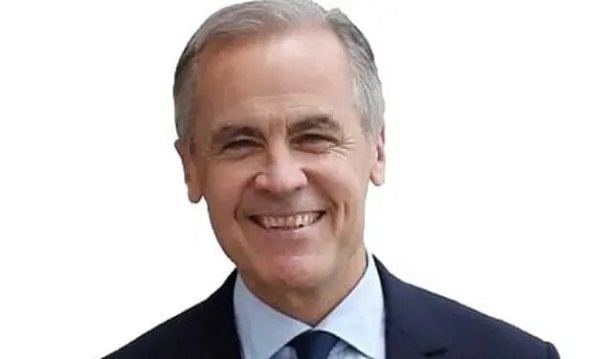

Carney’s spending makes Trudeau look like a cheapskate

This article supplied by Troy Media.

By Gwyn Morgan

By Gwyn Morgan

The Carney government’s spending plans will push Canada’s debt higher, balloon the deficit, and drive us straight toward a credit downgrade

Prime Minister Mark Carney was sold to Canadians as the grown-up in the room, the one who’d restore order after Justin Trudeau’s reckless deficits. Instead, he’s spending even more and steering Canada deeper into trouble. His newly unveiled fiscal plan will balloon the deficit, drive up

interest costs and put Canada’s credit rating and economic future in jeopardy.

When Trudeau first ran for office, he promised “modest short-term deficits” of under $10 billion annually and a balanced budget by 2019. Instead, he ran nine consecutive deficits, peaking at $62 billion in 2023–24, and nearly doubled the national debt, from $650 billion to $1.236 trillion. That

reckless spending should have been a warning.

Yet Carney, presented for years as a safe, globally respected economic steward, is proving to be anything but. The recently released Main Estimates (the federal government’s official spending blueprint) project program spending will rise 8.4 per cent in 2025–26 to $488 billion. Add in at least $50 billion to service the national debt, and the federal tab balloons to $538 billion.

Even assuming tax revenues stay flat, we’re looking at a $40-billion deficit. But that’s optimistic. The ongoing tariff war with the United States, now hitting everything from autos to metals to consumer goods, is cutting deep into economic output. That means weaker revenues and a much larger shortfall. Carney’s response? Spend even more.

And the Canadian dollar is already paying the price. Since 2015, the loonie has slipped from 78 cents U.S. to 73. Carney’s spending spree is likely

to drive it even lower, eroding the value of Canadians’ wages, savings and retirement funds. Inflation? Buckle up.

Franco Terrazzano of the Canadian Taxpayers Federation nailed it in a recent Financial Post column: “Mark Carney was right: He’s not like Justin Trudeau, he spends more,” Terrazzano argues. “The government will spend $49 billion on interest this year and the Parliamentary Budget Officer projects interest charges will be blowing a $70-billion hole in the budget by 2029. That means our kids and grandkids will be making payments on Ottawa’s debt for the rest of their lives.”

Meanwhile, Canada’s credit rating is under real threat. An April 29 report by Fitch Ratings warned that “Canada has experienced rapid and steep fiscal deterioration, driven by a sharply weaker economic outlook and increased government spending during the electoral cycle. If the Liberal program is implemented, higher deficits are likely to increase federal, provincial and local debt to above 90 per cent of GDP.”

That’s not just a red flag; it’s a fire alarm. A downgraded credit rating means Ottawa will pay more to borrow, which trickles down to higher interest rates on everything from provincial debt to mortgages and business loans.

But this decline didn’t start with tariffs. The rot runs deeper. One of the clearest signs of a faltering economy is falling business investment per worker. According to the C.D. Howe Institute, investment has been shrinking since 2015. Canadian businesses now invest just 66 cents of new capital for every dollar invested by their OECD counterparts; only 55 cents compared to U.S. firms. That means less productivity, fewer wage gains and stagnating living standards.

Why is investment collapsing? Policy. Regulation. Taxes. Uncertainty.

The C.D. Howe report laid out a straightforward to-do list, one the federal government continues to ignore:

Reform corporate taxes to attract capital investment.

Introduce early-stage investment incentives.

Tear down regulatory barriers delaying resource and infrastructure projects, especially in energy (maybe then Alberta won’t feel like seceding).

Promote IP investment with targeted tax credits.

Bring stability and predictability back to the regulatory process.

Instead, what Canadians get is policy chaos and endless virtue-signalling. That’s no substitute for economic growth. And let’s talk about Carney’s much-touted past. Voters were bombarded with reminders that he led the Bank of Canada during the 2008–09 financial crisis. But it was Jim Flaherty, Stephen Harper’s finance minister, who made the hard fiscal decisions that got the country through it. Carney’s tenure at the Bank of England? A different story. As former U.K. Prime Minister Liz Truss put it: “Mark Carney did a terrible job” at the Bank of England. “He printed money to a huge extent, creating inflation.”

Fast-forward to today, and Canada’s performance is nothing short of dismal. Our GDP per capita sits at just $53,431, compared to America’s $82,769. That’s not just a bragging-rights statistic. It reflects real differences in productivity, competitiveness and national prosperity. Worse, over the past 10 years, Canada’s per capita GDP has grown just 1.1 per cent, second worst in the OECD, ahead of only Luxembourg.

We remain a great country filled with capable people, but our most significant fault may be how easily we fall for image over substance. First with Trudeau’s sunny ways. Now with Carney’s global banker persona. The reality? His plan risks stripping Canadians of their prosperity, downgrading our creditworthiness and deepening long-term decline.

It pains me to say it, but unless something changes fast, Canadians face continued erosion in their standard of living and inflation-driven losses in their savings. The numbers are grim. The direction is wrong. And the consequences are generational.

Trudeau fooled voters with promises of restraint. Carney’s now asking for the same trust, with an even bigger bill attached. Canadians can’t afford to make the same mistake twice.

Gwyn Morgan is a retired business leader who has been a director of five global corporations

-

Alberta12 hours ago

Alberta12 hours agoAlberta Independence Seekers Take First Step: Citizen Initiative Application Approved, Notice of Initiative Petition Issued

-

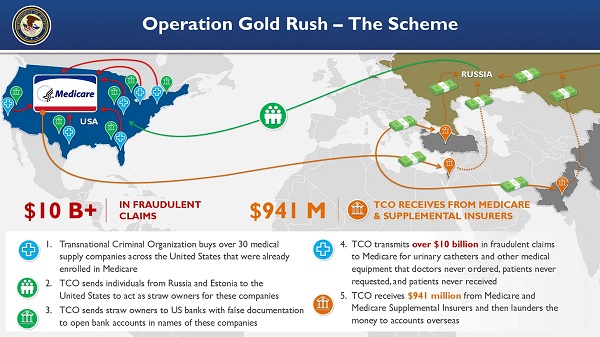

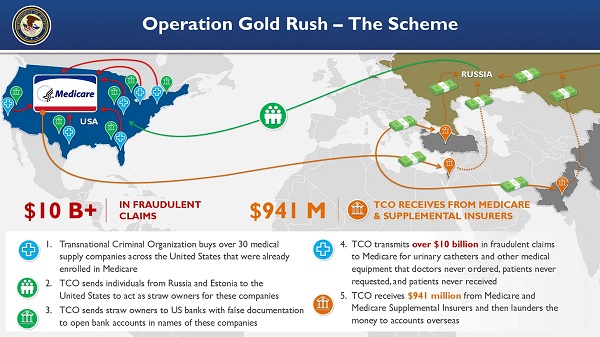

Crime11 hours ago

Crime11 hours agoNational Health Care Fraud Takedown Results in 324 Defendants Charged in Connection with Over $14.6 Billion in Alleged Fraud

-

Health10 hours ago

Health10 hours agoRFK Jr. Unloads Disturbing Vaccine Secrets on Tucker—And Surprises Everyone on Trump

-

Bruce Dowbiggin13 hours ago

Bruce Dowbiggin13 hours agoThe Game That Let Canadians Forgive The Liberals — Again

-

Alberta1 day ago

Alberta1 day agoCOVID mandates protester in Canada released on bail after over 2 years in jail

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoCanada’s loyalty to globalism is bleeding our economy dry

-

Crime2 days ago

Crime2 days agoProject Sleeping Giant: Inside the Chinese Mercantile Machine Linking Beijing’s Underground Banks and the Sinaloa Cartel

-

armed forces1 day ago

armed forces1 day agoCanada’s Military Can’t Be Fixed With Cash Alone