Crime

“Fake Chinese income” mortgages fuel Toronto Real Estate Bubble: Canadian Bank Leaks

Canadian Banking Money Laundering Investigation Reposted in Light of Ottawa’s Fentanyl Czar Pledge

In response to Ottawa’s pledge to tackle fentanyl-linked money laundering—including the appointment of a “fentanyl czar” and new intelligence-sharing initiatives with the United States—The Bureau is reposting this February 2024 investigation estimating tens of billions, potentially several hundred billion, laundered through Vancouver and Toronto real estate via underground banking networks tied to China and global narcotics trafficking, including fentanyl.

FINTRAC’s 2023 analysis of 48,000 transactions involving members of the Chinese diaspora exposed vast wire transfers from Hong Kong and Mainland China, funneled through “money mule” accounts linked to students, homemakers, and shell businesses—including law firms. These findings raised serious concerns about Canada’s banking oversight but led to no prosecutions in Canada. The study also revealed laundering patterns central to the U.S. Justice Department’s $3 billion TD Bank case, with international students from China working with Beijing’s United Front networks playing key roles in the TD Bank money laundering, according to U.S. investigator David Asher, a former Trump Administration official. The revelations underscore how the so-called “Vancouver Model”—once centered on laundering drug proceeds through British Columbia government casinos—evolved during the COVID-19 pandemic, embedding itself deeper into Canada’s banking and legal systems. These findings align with research from SFU urban planner Andy Yan, who has documented how foreign capital distorts Canada’s housing market, with mortgage approvals and home purchases far exceeding reported local incomes.

At the heart of this investigation is HSBC Canada whistleblower “D.M.,” who believes they uncovered at least $500 million in dubious Toronto-area mortgages backed by fabricated remote-work salaries from China. After raising the alarm internally, D.M. says HSBC Canada introduced only superficial reforms and pressured him to delete critical records—deepening his conviction that Canada’s financial oversight remains dangerously weak.

Former RCMP investigators Garry Clement and Cal Chrustie, who reviewed D.M.’s evidence, warn that systemic vulnerabilities persist. Chrustie—who has extensively documented Canada’s weak regulations enabling underground banking linked to organized crime in China, Iran, and Mexico—pointed to the 2012 U.S. Justice Department case where HSBC was fined $1.9 billion over $881 million in cartel-linked transactions involving Mexico’s Sinaloa cartel and Colombia’s Norte del Valle cartel.

As Andy Yan has emphasized, governments at all levels bear responsibility for enabling foreign capital to flood Canada’s housing market without adequate transparency. “When you have programs designed to domesticate foreign capital into local real estate, you see these income-to-home-price incongruities,” he said.

Ottawa’s new fentanyl czar is tasked with coordinating intelligence-sharing and enforcement actions with U.S. agencies to disrupt fentanyl trafficking and related money laundering. Trudeau’s government has also pledged to designate cartels as terrorist organizations, a move that could have sweeping consequences for Canadian banks by exposing them to heightened U.S. financial scrutiny and enforcement actions.

It remains to be seen what position Liberal Party leadership favourite Mark Carney—former Governor of the Bank of Canada (2008–2013) and the Bank of England (2013–2020), and a globally influential banker—will take on Canada’s ongoing struggles with financial crime and illicit capital flows. While the Bank of Canada does not oversee financial crime enforcement, Carney’s extensive experience in international financial regulation—gained through his roles involving oversight at global institutions such as the Bank for International Settlements and his active participation in forums on financial stability—suggests he could offer valuable insights into Canada’s banking vulnerabilities. This is particularly noteworthy as he emerges as a political contender and potential Prime Minister.

OTTAWA, Canada — The whistleblower, a Canadian business school graduate, was staggered by the suspicious home loans he discovered in 2022 when he joined a mortgage approval team in a small HSBC branch on the outskirts of Toronto.

He knew of suspicions surrounding Chinese capital in British Columbia real estate, but had never witnessed shady lending while working at an HSBC branch in Campbell River, a bucolic town on the coast of Vancouver Island.

When he arrived at HSBC’s bank in Aurora, an affluent suburb north of Toronto, he discovered explosive growth in home loans to Chinese diaspora buyers during the Covid-19 pandemic.

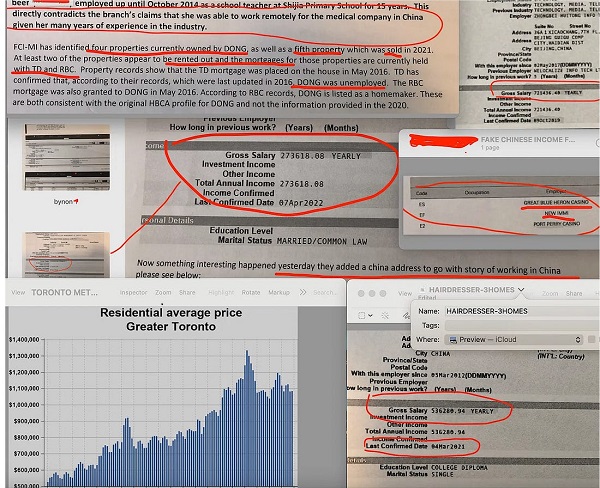

Chinese migrants living across Toronto were obtaining mortgages from HSBC while supposedly earning extravagant salaries from remote-work jobs in China. In one example, an Ontario casino worker that owned three homes also claimed to earn $345,000 in 2020 analyzing data remotely for a Beijing company.

Before joining HSBC Canada, the whistleblower had studied fake-income mortgage frauds for his Business Masters degree at Vancouver Island University. After arriving at Aurora in February 2022, while digging into the branch’s loan books and interrogating his colleagues, he made mind-blowing assessments.

Since 2015, the whistleblower concluded, more than 10 Toronto-area HSBC branches had issued at least $500-million in home loans to diaspora buyers claiming exaggerated incomes or non-existent jobs in China.

These foreign-income scams spiked during the pandemic, the whistleblower believed, because borrowers could somewhat plausibly claim to be working remotely in other countries while riding out Covid-19 in Canada.

While a small bank of Aurora’s size was expected to issue about $23-million in residential loans every year, this branch had shovelled out $88-million in mortgages in 2020, according to the whistleblower, and over $50-million in 2021.

The whistleblower, whomThe Bureau is calling D.M., immigrated to Canada as an international student from India, making him a minority among mostly Chinese-Canadian co-workers at the Aurora branch.

As D.M. probed his colleagues, his belief gained conviction, that HSBC Canada and other Canadian banks including CIBC had systemic problems with highly questionable mortgages issued to diaspora buyers with unverified sources of wealth in China.

Losing sleep, in April 2022, D.M. sent an audacious email to senior bank executives: “I am going to reveal potential mortgage fraud at HSBC Bank Canada and possibly some employees benefited from the fraud, financially pocketing thousands of dollars, which I call the proceeds of crime.”

D.M.’s explosive four-page complaint triggered an internal investigation that led to some reforms at HSBC Canada according to internal emails obtained by The Bureau.

But more than a year later, D.M. was so dissatisfied with the bank’s response that he risked sharing his story and numerous internal documents for an unprecedented journalistic investigation into Canada’s housing affordability crisis.

“I found out a huge mortgage fraud showing borrowers with exaggerated income from one specific country, China, pretending to be working remotely,” D.M. informed The Bureau in June 2023. “I believe the housing prices in Toronto are linked to this, because this is about income verification in banks, which is supposed to moderate demand.”

The Bureau asked HSBC Canada to review emailed information for this story and provide an appropriate manager for an interview regarding D.M. ‘s records and allegations.

“I won’t have anyone to speak with you directly,” Sharon Wilks, Head of Communications, responded. “But for context: As a global bank, HSBC is at the forefront of efforts to identify, prevent and deter financial crime … We will not do business with individuals or entities we believe are engaged in illicit conduct.”

Wilks added that HSBC Canada “can and do regularly exit relationships with clients whose activities we deem too risky.”

The Bureau’s seven-month investigation into D.M.’s allegations suggests HSBC Canada and other Canadian banks could have issued many billions of dollars in questionable mortgages to Chinese diaspora buyers, and a significant cause of Canada’s real estate bubble is hundreds of billions in illicit fund transfers from China into Canada, and bank lending that amplifies its impacts, especially in Toronto and Vancouver home prices.

“There are thousands of these cases, large scale,” D.M. said in an interview. “Hardworking Canadians are denied mortgages and these Chinese residents forge documents and get mortgages approved, heating up the already hot Ontario real estate markets.”

“These people don’t have steady jobs or income in Canada,” he alleged, “but what they are doing is scams to launder money, and get mortgages using fake documents.”

The Bureau’s investigation included asking seven prominent Canadian experts to assess some of D.M.’s documents, allegations and conclusions.

This investigation suggests D.M. ‘s calculation is plausible, that the Aurora branch and other Toronto-area HSBC branches have issued at least $500-million in questionable Chinese income loans since 2015.

But D.M’s findings could also change the public’s understanding of housing affordability in Toronto and Vancouver, a politically explosive issue expected to frame Canada’s upcoming federal election.

This is because, according to the academics and criminologists that reviewed D.M.’s documents with The Bureau, his evidence fits into FINTRAC’s much broader examinations of suspicious real estate and banking transactions.

In 2023, the anti-money laundering watchdog published a ground-breaking study into 48,000 Chinese diaspora banking transactions.

FINTRAC found that during the Covid-19 pandemic, because Canadian casinos were closed, Chinese underground banking schemes evolved, flooding electronic fund transfers from Hong Kong into Canadian bank accounts that served like corridors for murky real estate transactions.

The Bureau’s analysis also finds that what D.M. discovered in Toronto banks, finally sheds light on mysterious capital flows discovered by a prominent Canadian academic in 2015, in a study of Vancouver land titles and mortgages.

That examination of $525-million worth of real estate purchases in a six-month period found 66 percent of buyers in several affluent neighbourhoods were recent Chinese diaspora migrants, and most mortgages went to buyers with little or no income in Canada.

Similarly, what D.M. found in his probe of pandemic-era loans could be called the evolving “Toronto Method” of an underground banking system discovered first in Vancouver, and found to be laundering a stunning $1.2-billion in cash from Mainland China through British Columbia government casinos in 2014.

This system of shadowy transfers was dubbed the “Vancouver Model” by an Australian professor, and brings together transnational organized crime, affluent Chinese nationals seeking to export their wealth abroad, and Canadian casinos, banks and real estate, in transactions that evade policing because the pivotal cash exchanges are done off the books by professional money launderers serving the global Chinese diaspora.

According to FINTRAC’s 2023 study of 48,000 pandemic-era transactions, this evolving Vancouver Model network “simultaneously facilitates money laundering and the circumvention of Chinese currency controls”

“As a result of the temporary closures of Canadian casinos due to the COVID-19 pandemic, professional money launderers began to diversify their money laundering methods,” FINTRAC’s study says.

“During this time, FINTRAC observed a rise in money laundering typologies involving transferring large sums of funds to Canada from foreign money services businesses, often located in China, notably Hong Kong, and the laundering of the funds primarily through the real estate, securities, automotive and legal professions.”

These wire transfers from China were routed into bank accounts of “multiple, unrelated individuals in Canada,” that served as “money mules” in byzantine networks involving Canada-based real estate developers, real estate agents, mortgage brokers and banks.

These Chinese diaspora bank account owners often claimed they were students, homemakers, office managers, or unemployed, FINTRAC reported.

They sometimes used their accounts to send bank drafts to others in Canada for home purchases, or served as “straw buyers” for offshore investors.

“Mortgage payments are sourced from incoming funds from China,” FINTRAC’s alert said.

FINTRAC’s study doesn’t say that Canadian banks knowingly issued fake-income mortgages to Chinese diaspora buyers in Toronto.

But in an interview, D.M. said banking staff are trained to guard against fraud, and the loan application packages he reviewed in Aurora beggared belief.

“The bank found out that one lady works in a casino part-time but got a $1.4 million mortgage showing over $300,000 annual income,” he said. “Plus she takes money as benefits from the government, for her two kids.”

In other examples, an HSBC mortgage client claimed to earn $700,000 annually for remote work in China, while simultaneously living in Canada and paying off a $10,000 student loan.

Another woman who owned homes in Aurora, Markham and Scarborough, worked part-time as a hairdresser while also claiming to earn $536,280 at a “Business Manager” job in Guangzhou.

“Canadian workers have been put out of the real estate market by people working as a hairdresser that own a couple homes,” D.M. said in an interview.

“How is that fair?”

The most shocking case reviewed by The Bureau, shows that one woman that owns at least four Toronto properties opened her HSBC Aurora bank account in 2013, claiming to be a “Homemaker with no annual income.”

But her Toronto account soon received incredible amounts of wire transfers from HSBC China accounts, and paid out “high value cheques” to third parties for real estate purchases.

This case suggests “Toronto Method” shadow banking described in FINTRAC’s 2023 study has been seeping into Toronto real estate for about a decade.

And yet in 2020, this same woman applied for another HSBC Canada mortgage, claiming to earn $763,000 remotely from her job in China.

This evidence from the HSBC whistleblower complements the seminal investigations of Simon Fraser University academic Andy Yan, who examined sales from August 2014 to February 2015 in several communities on Vancouver’s westside. The average home price in Yan’s study was $3-million.

Looking back at his Vancouver findings in comparison to D.M.’s Toronto banking documents, Yan told The Bureau “I think this helps affirm some of my early work that I did, almost nine years ago.”

“This goes to the core of our banking system,” he said, “and how are we verifying identities and how are we verifying incomes.”

In Yan’s controversial study the vast majority of mortgages went to buyers listing their occupation as home-maker, followed by students, and managers. HSBC and CIBC were the dominant lenders.

Unlike the HSBC whistleblower, Yan had no access to internal banking data regarding the purported origin of funds behind these mortgages taken by Chinese diaspora buyers.

But in an interview, Yan said what he found most interesting back in 2015, was suspicions that Chinese migrants were often buying homes with bulk cash, weren’t accurate. The truth was more complex and seems to be clarified by D.M.’s mortgage findings in Toronto.

“It’s about that global flow of capital, and how it’s multiplied by Canada’s mortgage and lending system,” Yan said. “Because you have to remember, one of the biggest conclusions about my study was that it wasn’t bags of cash that were being used to purchase Vancouver homes outright. They were loans being used. So now, I’m thinking, this is where my study connects up to what you have discovered in Toronto.”

“The interesting story here,” Yan added, “is what happens in Toronto real estate may not repeat Vancouver, but it perhaps rhymes.”

Probably the most famous Chinese property owner from Yan’s 2015 study areas is Huawei executive Meng Wanzhou. In 2009 her family bought a home in Vancouver’s Dunbar neighborhood for $2.73 million, land titles show. In 1998, ten years before Vancouver Model transactions started to surge in Vancouver real estate, the home was sold for $370,000. The home is now valued at almost $6-million.

Ashleigh Rhea Gonzales, a former RCMP data scientist who recently published a criminology thesis finding Chinese diaspora underground banking causes significantly more money laundering into Canada’s real estate than previously estimated, said that D.M.’s findings resemble her own Vancouver Model research.

“This whistleblower’s allegations of widespread mortgage fraud at HSBC Canada align with some of the first-hand accounts from staff of some Canadian financial institutions that I have come across in my research on money laundering in British Columbia,” Gonzales said.

Gonzales, who worked for RCMP’s anti-gang unit in British Columbia until 2023, says she found reports of mortgage fraud accelerated “during the uptick in the Canadian housing bubble after the Vancouver 2010 Olympics,” and continued to surge from 2015 to 2018.

With all this considered, and comparing data sources in this story with previous evidence confirmed in British Columbia’s Cullen Commission, The Bureau estimates that from 2014 to 2023, well over $200-Billion in Vancouver Model and Toronto Method funds could have poured through underground diaspora networks and Canadian financial institutions into Toronto and Vancouver’s real estate.

A federal official not authorized to comment publicly also examined D.M.’s banking leaks for The Bureau, and called this information “explosive.”

The official said money laundering is increasing in Canada, and D.M.’s belief that Chinese-income mortgage fraud has boosted home prices in Toronto is likely true, but also should apply for Vancouver and Montreal real estate prices. The official noted that other nations require tax agencies to verify incomes for mortgages, which isn’t the case in Canada.

“It matters for our next generation because of the impact on the housing market,” the official said.

Queen’s University professor Christian Leuprecht – editor of Dirty Money, a new academic text that probes how Ottawa’s weak regulation has “turned the Canadian federation into a destination of choice for global financial crime” – also reviewed some of D.M. ‘s leaks.

“It’s not a new problem, but you’re taking it to the next level,” Leuprecht said.

“Why does this matter? Because organized crime isn’t just laundering their ill-gotten gains, like any good business person, when they buy real estate, they generate a down payment, then get a mortgage for the rest. Why buy one property when you can buy four?”

“Do you know how many mortgage frauds we have in our books?”

The Bureau’s review of HSBC Canada emails and D.M.’s text messages, shows he came to believe numerous employees at the Aurora branch had direct knowledge of faked Chinese income mortgages, and a veteran manager with oversight of more than 10 Greater Toronto branches knew about broad and questionable mortgage lending for Chinese diaspora clients.

Months after D.M. blew the whistle internally he exchanged texts with another employee, identifying colleagues that they believed had knowledge of diaspora mortgage scams.

The texts suggest D.M. believed HSBC Canada and other Canadian banks continued to hold vast amounts of suspicious foreign income mortgages, which could cause systemic loan quality risks if Toronto’s real estate prices decline.

“Do you know how many mortgage frauds we have in our books,” D.M. texted to his colleague. “It’s insane.”

“She told me,” the colleague replied, referring to an HSBC branch manager.

“She was like, if you do come, you gotta be prepared for the mortgage payout.”

“These people showed fake income and got mortgage,” D.M. continued. “Now interest rate is high, they can’t cope.”

“Other branches did the same thing too,” his co-worker replied. “I heard there’s a lot.”

“Absolutely,” D.M. texted. “All branches engaged in it.”

“This is like the unspoken secret,” his co-worker concluded. “I’m pretty sure other banks have it too. My Aunt have no income and got a mortgage for 700k. They just need a Covenanter from China.”

Generally, in mortgage contracts a covenanter takes responsibility for the loan if the primary borrower defaults.

Internal records reviewed by The Bureau confirm that on April 18, 2022, D.M. sent a lengthy complaint email to senior HSBC Canada executives, informing them of allegations he’d learned from his colleagues.

In it, he alleges that an Aurora manager had informed him of a complaint letter posted to the branch, that accused mortgage brokers and branch employees of colluding in scam mortgages emanating from Mainland China fraud networks.

Pointing to specific examples, D.M. claimed that another branch colleague had admitted processing numerous loan applications without meeting his clients, because a branch manager delivered her subordinates foreign income client applications so “they did not have to get sales themselves.”

“Surprisingly all these clients he would get will have foreign income most of the time very inflated like 400k or 670k a year,” D.M. wrote. “To me that’s suspicious, but he never questioned the branch manager because in Asian culture it’s disrespectful to question elders.”

D.M. also informs his bosses that one Aurora bank manager opened up to him, saying she believed allegations of mortgage fraud collusion involving some branch staff.

“She said yes, she knows specially in Mainland China there is a team who would even answer emails and phone calls verifying [Chinese income] but it’s a sophisticated and well organised scam,” D.M. ‘s email to HSBC Canada managers says.

His complaint explains that he continued to press an Aurora bank manager on her knowledge of fraud allegations.

“When I asked for such a serious issue if she raised a HSBC confidential [complaint] or not she evaded my question,” D.M. wrote. “Now we all love numbers, but I don’t think the bank will like these kinds of numbers achieved through this way.”

Describing why he contacted HSBC Canada executives directly, the whistleblower’s complaint says he felt confused and isolated, but D.M. decided “local leadership if not participated, at least turned a blind eye,” to Chinese fake-income scams, forcing D.M. to “bring up a serious issue against people of superior positions.”

“I could not have stayed silent, in fact I could not sleep well thinking about it,” his April 2022 complaint says. “It reminds me to some extent what happened with the Home Capital Group.”

“The whole thing is wrong on so many grounds,” D.M. continued.

“Now I know one more reason why Canadians and permanent residents are not getting into the housing market. It’s not only HSBC such things are happening across other Canadian banks as well.”

In the Home Capital case, the Ontario Securities Commission fined the prominent Ontario-based subprime mortgage lender in 2017, alleging Home Capital failed to disclose several of its mortgage brokerages had major problems with faked-income mortgages.

D.M. concluded his four-page complaint to senior executives, writing: “I recommend all mortgage deals of this branch in the last 3 years at least if not longer with Foreign income be probed.”

“Bank statements can be verified directly with the foreign banks or use a reputable third party to verify,” he suggested. “When we find someone with Fake ID or trying to impersonate someone we call the cops. But these people, both staff nor clients who did fraud were reported.”

Hours later on April 18, 2022, an HSBC Canada executive emailed back: “I am going to refer this to our Fraud and Risk teams and they will investigate your concerns.”

“The Implications are Broader”

The next day D.M. continued to hound HSBC Canada managers with emails to support his allegations, spotlighting the absurdity of massive Chinese remote incomes claimed by diaspora buyers.

He pointed to one woman with a $1.6-million HSBC Canada mortgage.

“The client claims to be in Canada but [is] a office supervisor in China. [In the] age of remote working in which country [does] a office supervisor makes 400k please tell me,” D.M. wrote.

“[W]hen I asked the co-worker she said her job is not to use the brain or be a police, when I asked do you think she makes that kind of money and how is she doing her job being in Canada to be an office supervisor in China[?]”

Pointing to another document, D.M. warned his managers about Ms. Chen, who claimed to make $721,000 annually as “project manager” for a Beijing telecommunications company, to secure a $1.89 million mortgage.

Again on May 4, 2022, D.M. emailed executives, suggesting internal records for an Aurora client named Ms. Lin had been altered soon after D.M. blew the whistle on fake Chinese income loans.

His email, which included Ms. Lin’s client profile, warned: “Something interesting happened yesterday, they added a China address to go with [the] story of working in China, please see below.”

The Aurora branch banking records disclosed to The Bureau show that Ms. Lin owns three homes in the blocks surrounding Pacific Mall in Markham.

“The client was onboarded on 24th March with Canada address only and Canadian tax residency,” D.M.’ s email continued.

“She claims to be working in China and have foreign income, so the story she is stuck in Canada due to Covid is very interesting. Suddenly yesterday she decided her address in China. Someone saw the discrepancies and the branch team decided to change it.”

“To me that’s a red flag done to align with the story portrayed.”

Next, D.M. exposed Ms. Lin’s foreign income claim.

“She works for Food processing company, a logistics officer making 273k a year,” he wrote. “I don’t know which logistics officer can work when physically in a different company and also who makes 273k working as a logistics officer.”

Citing another internal banking record, D.M.’s email pointed to Ms. Lin’s $273,000 income and said “it’s interesting how they did the verification.”

The email continues to explain that branch records showed Ms. Lin and her husband had a joint mortgage with a balance of $497,000 at CIBC.

But suddenly during Covid-19, Ms. Lin applied for a new mortgage for $1.2 million with HSBC Canada.

“When I see such things I can’t stay quiet,” D.M.’s May 2022 email says. “[I] was assuming with the new rules things will stop, [but] declining the mortgage or retraining the staff is like treating the symptoms.”

He added that many suspicious Chinese income loans had been “flagged by our Fraud Team already.”

The whistleblower’s scathing assessment ends with the observation that D.M. didn’t believe “someone woke up and decided to scam the bank, but [worked with] a sophisticated network of agents who are training people what to say and answer.”

“The implications are broader and as a responsible bank and citizen we have to,” request investigations from the Canadian Revenue Agency or Ontario Provincial Police, D.M. asserted.

The Bureau asked Gonzales, the former RCMP data scientist, to review some of D.M.’s documents and conclusions.

“From what I have reviewed, D.M.’s findings align with what appear to have been commonplace practices by some groups of staff complicit from the front line, middle office, and back office and sanctioned by management,” Gonzales wrote, adding “whether knowingly or not depends on the individual work cultures.”

The Bureau also asked Stephen Punwasi to review D.M. ‘s leaked banking documentation.

Punwasi is a financial expert who founded Better Dwelling, a real estate analysis website with a large following of young professionals trying to understand why they’re excluded from home ownership in Canadian cities.

He also provided analysis for British Columbia’s 2018 report into Vancouver Model money laundering in casinos, real estate and luxury vehicles.

What Punwasi explained to the report’s author, former RCMP executive Peter German, is that even though Vancouver Model money launderers don’t comprise a majority of buyers in Vancouver, their willingness to overbid on home sales causes ripples that sends prices skyrocketing, especially during times when political turmoil inside China triggers increased capital flight.

“In 2015 and 2016 Ontario saw this flood of money from China, just like British Columbia, and it was not just to do with immigration, it was due to President Xi’s political crack down on corruption,” Punwasi said. “I think we’ve seen that capital flight in Ontario and B.C. in two big cycles, also including 2020 and 2021.”

The Bureau asked Punwasi if the banking records disclosed by D.M. help to explain Toronto’s real estate price surges.

“Absolutely,” he said, pointing to the case of Ms. Lin (who claimed a $273,000 remote-work income in China) and her three homes surrounding Markham’s Pacific Mall.

Property buyers that aren’t shopping for shelter, but for capital flight or money laundering vehicles, are what Punwasi terms the “marginal buyer.”

“The marginal buyer is like an exuberant buyer on crack, so if they are motivated to move as much money as possible,” he said, “the larger the mortgage they can get, it helps them to overpay for homes, and that can cause the price to launch.”

“So if you see a townhome in Toronto going for $2-million, you don’t know if it is mortgage money laundering or someone buying a place to live. You just have to compete with the going price.”

Punwasi says housing prices are a powerful political issue that will shape the next federal election.

But at the same time, young generations are confused by competing explanations on the causes of Canada’s housing affordability crisis, Punwasi believes, whether its lack of housing supply due to restrictive zoning bylaws, or increased demand due to recent immigration surges, or other factors that make Canada’s housing bubble an outlier in the Western world.

“There are so many conflicting narratives right now that people find it hard to believe the scale of impact that money laundering can have on Toronto real estate prices,” Punwasi said. “But no one has thought it through, that having criminals run our renting stock is a liability.”

Punwasi also believes that Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s government has decreased scrutiny of money laundering in recent years.

He points to new data uncovered in a ministerial inquiry from Conservative MP Adam Chambers, who is a proponent of tougher money laundering laws, which found sharp declines in Canadian Revenue Agency audits of FINTRAC leads.

“The systemic corruption in housing has been snowballing,” Punwasi said, “to where it’s turned into, maybe the banks don’t need to check where the incomes are coming from, and now whole generations can’t find stable shelter.”

“Delete, delete, delete”

HSBC Canada emails reviewed by The Bureau show that while the bank appears to have responded to some of D.M. ‘s recommendations in 2022, troubling mortgage applications and problems with existing Chinese income loans continued.

A January 2023 email to an Aurora branch manager from HSBC Canada’s office in Montreal pointed to a client named Ms. B., who worked at an Ontario government casino, and owned homes across Toronto, in Richmond Hill, Newmarket and East York.

Documents show she obtained an HSBC Canada mortgage for $1.26 million in 2016, and that HSBC Canada staff “confirmed” in July 2021 that she was earning $345,000 with a remote work job in Beijing.

Despite her incredible claimed income, documents show, Ms. B. was having trouble paying at least one of her three mortgages.

An email from a “Senior Loss Mitigation” employee in Montreal to an Aurora branch employee says: “client is going through a tough time … her income is limited … I know she collect rent and she use it to pay her second mortgage. Please review the situation with the client to see if there is any special agreement available to her.”

But Aurora’s branch wrote back to the Montreal branch: “What we have told her is … if she really can’t pay, then she just have to put her house for sale … but she doesn’t want to do that.”

In an interview D.M. told The Bureau this case was typical.

“What they are doing is AirBnBing these properties,” he said. “But they can’t manage with higher interest rates.”

He said during mortgage application interviews at the Aurora branch he would often look across his desk and ask questions without letting clients know he was looking at their income claims from purported Chinese companies on his computer screen.

“Most of these people don’t even know what type of company is in their job profile,” he said.

And documents reviewed by The Bureau show that mortgage applications consistent with Fintrac’s 2023 Chinese money laundering report continued in Aurora.

In May 2023, D.M. emailed a senior HSBC Financial Crime Compliance investigator, writing “Just came across two profiles of clients and I have strong evidence these mortgages were also obtained with fake docs and fraudulently.”

When the investigator responded “I will take a look,” D.M. replied: “One had a CDA student loan of 10k and making 700k in China. Makes no sense, there are many other anomalies.”

In interviews, D.M. told The Bureau he waited “patiently for a year” after reporting his Chinese-income mortgage concerns to HSBC Canada managers, before concluding the bank’s response was insufficient.

“This has been going on for seven years and no one spoke up,” he said. “In my first meeting last year, they asked me a lot of questions, like why didn’t you use the normal channels? But I had no faith in the normal channels.”

“Many bank staff were obviously involved,” D.M. alleged. “It was not one or two employees turning the blind eye but the entire system, someone verifying those fake offer letters and pay stubs, or their bank statements from China.”

D.M. said his concerns also included HSBC Canada’s proposed sale to RBC, which was announced in 2022, about six months after D.M. ‘s April 2022 internal complaint. The sale was approved in December 2023 by Canada’s deputy Prime Minister Chrystia Freeland.

Christian Leuprecht, among other experts interviewed for this story, agreed that D.M.’s allegations of widespread Chinese-income frauds at HSBC Canada could raise questions about whether Freeland, Canada’s finance minister, had knowledge of mortgage lending investigations inside HSBC when she approved the sale.

Freeland directed RBC to “establish a new Global Banking Hub in Vancouver,” and “maintain Mandarin and Cantonese banking services at HSBC branch locations,” a Department of Finance statement says.

Ultimately, D.M. says he chose to share his story with Canadian citizens partly because he felt pressured to erase evidence from his whistleblower complaint emails.

A June 2023 email from the bank’s personnel department says “we hereby demand that you immediately and permanently delete any and all HSBC information on any personal email accounts.”

Crime

How Chinese State-Linked Networks Replaced the Medellín Model with Global Logistics and Political Protection

Zhenli Ye Gon, aka “El Chino” ran a meth empire from Mexico City supplied and set up by a Chinese Communist Party linked conglomerate called Chifeng Arker.

The Rise of ‘El Chino’ — A New Blueprint for Beijing’s Narco-Industrial Power

In the 1980s and ’90s, U.S. agents dismantled the Medellín Cartel not by chasing Pablo Escobar directly, but by targeting the structure around him—the lawyers, accountants, and corporate fixers who laundered his fortune. For Don Im, a key figure in the DEA’s inner circle during that campaign, it was a hard-won lesson that stayed with him across decades of global narcotics investigations.

“You can take down the cartels all you want—cartels are easy to replace,” Im told The Bureau. “It’s the bankers, the businessmen, the lawyers, and the accountants that are harder to get. Because they’re the inconvenient targets.”

By “inconvenient,” Im means politically protected. Ultimately, geopolitically protected.

Today, he sees history repeating itself—only on a far more dangerous scale. Where Colombian cocaine traffickers once flooded American cities, Chinese-backed methamphetamine and fentanyl empires now dominate, shielded by Party-state logistics and financial infrastructure. The operations are more sophisticated—executed with near impunity.

“I worked with Steve and Javier,” Im said, referencing DEA agents Javier Peña and Steve Murphy, the duo immortalized in Narcos. “And how Pablo was taken down? His accountants and lawyers were the first to be removed. That made Pablo a bigger, more vulnerable target. Unless we go after the facilitators—accountants, lawyers, businessmen, and corrupt government officials—you’re never going to affect the illicit drug trade or the money it generates.”

That insight brings Im back to a dilemma that continues to trouble him, even three years into retirement: how to dismantle narco empires entrenched in Canada and Mexico, shielded not only by senior Chinese Communist officials profiting from the fentanyl trade, but also by troubling ties to Western political figures. The conundrum, he says, is captured in what some DEA veterans view as the most overlooked turning point in global narco-trafficking—the rise of Chinese-Mexican pharmaceutical magnate Zhenli Ye Gon.

Now imprisoned in Altiplano, Mexico’s maximum-security fortress, Ye Gon was a legendary figure in Las Vegas—dubbed the “Mexican-Chinese whale” for his extravagant losses at casinos like the Venetian, where he gambled over $125 million between 2004 and 2007, all while running a billion-dollar methamphetamine empire.

His ascent in Western Hemisphere drug trafficking was too rapid to be accidental.

“I think he arrived in Mexico City in 1998 or 1999,” Im recalled. “And then within two years, he received Mexican citizenship from President Vicente Fox. So that shows you how influential and effective he was in penetrating the highest levels of the Mexican government.”

Once established in Mexico, his pipeline to CCP-linked suppliers began flooding Mexican ports—with a high-end production facility built with technical assistance from China.

“He’s still in prison asking for another $270 million back—after $207 million was already seized,” Im said, his voice tightening with outraged disbelief. “And he’s still sitting there. He was the largest pseudoephedrine importer from China into Mexico. His companies and infrastructure are still intact.”

When asked who is running the infrastructure today, Im didn’t hesitate.

“His associates and his family members.”

“He imported seven or eight high-powered, top-of-the-line pill press machines from Germany—each capable of cranking out at least half a million pills every two days,” Im said. “The Mexican authorities seized one.”

That leaves a troubling question: Have the remaining pill presses continued producing fentanyl-laced counterfeit oxycodone pills for the past decade—operated by Ye Gon’s family members and Chinese-linked criminal associates, in alliance with the Sinaloa Cartel—even as he sits in prison, with impeccable supply ties to Chinese Communist Party-controlled precursor firms still intact?

The Bureau’s review of DEA records and U.S. extradition documents suggests Ye Gon’s operations extended far beyond chemicals and a single Mexican factory built with assistance from a Chinese precursor supplier. His financial network revealed a laundering architecture as vast and deliberate as his synthetic drug supply chain.

According to DEA calculations, Ye Gon’s company illegally imported nearly 87 metric tons of a key methamphetamine precursor over just a few years—enough to yield more than 36 metric tons of high-purity meth. At conservative estimates, the precursor was worth over USD $188 million. Once converted and sold on American streets, the finished product could generate more than USD $724 million.

Chemical Supply Meets Political Shield: Chifeng Arker’s Role in the Fentanyl Pipeline

On September 24, 2003, Ye Gon’s Mexico-based firm, Unimed México, signed a supply contract with Chifeng Arker, a company based in Inner Mongolia with links to Shanghai. The deal called for the annual purchase of at least 50 metric tons of a chemical used to manufacture pseudoephedrine—a primary precursor in the production of methamphetamine. Once processed, the substance forms the essential base for high-purity crystal meth.

While Washington remains rightly focused on the toll of fentanyl, Im says the devastation wrought by methamphetamine is comparable. Beyond generating revenue to fund fentanyl production, meth ravages communities and drains health care and policing budgets in blighted states.

The scale at which Ye Gon operated—importing dozens of tons of precursors and building a high-end production plant—could not realistically have been achieved without tacit support from elements of the Chinese state.

In effect, Chifeng Arker agreed not only to supply enormous volumes of this chemical, but also to support Ye Gon in running his Mexican production plant.

“The contract also called for Chifeng Arker to provide technical support to aid Unimed in the actual production of pseudoephedrine, to include ‘workshop housing design,’” U.S. government extradition records state. “In October 2005, Ye Gon began to build and equip a manufacturing plant in Toluca, Mexico, with the help of Chinese advisors, as contemplated by the September 2003 contract with Chifeng Arker.”

Both Ye Gon and his chief chemist, Bernardo Mercado Jiménez, signed the agreement.

Court records suggest Ye Gon and a team of Chinese workers were directly involved in methamphetamine production.

“Chinese workers helped with the start-up of that plant, as contemplated by the Chifeng Arker contract,” states a 2013 U.S. District Court extradition filing from West Virginia. The filing continues: “According to workers at the plant, the facility received daily shipments of a white, hard chemical substance that was heated with hydrochloric acid to obtain a white crystalline powder. … At the end of the day, that powder was bagged and driven away by Ye Gon or his personal driver.”

Pursuant to the contract, shipments of precursor chemicals flowed from China to Mexico between 2004 and 2006. After mid-2005, Mexico revoked its license amid a chemical diversion crackdown. Ye Gon and Chifeng Arker shifted to more covert methods.

Evidence from U.S. court and extradition records shows that at least four large illicit shipments—totaling tens of thousands of kilograms—were dispatched in 2005 and 2006. To avoid scrutiny, they were routed through a Hong Kong shell company called Emerald Import & Export and labeled misleadingly.

During this period, Chifeng Arker effectively served as Ye Gon’s offshore factory, supplying raw materials for meth production.

The financial connection ran just as deep. Ye Gon used Mexican currency exchanges—casas de cambio—to launder payments to Chifeng Arker. In one documented instance, a single exchange processed three payments totaling $2 million USD to Arker, timed to coincide with the Hong Kong shipments.

Corporate record searches show that Chifeng changed its ownership structure after scrutiny from U.S. authorities. Its current parent company in Shanghai—publicly traded in Hong Kong—is nearly 50 percent owned by state-controlled or linked pharmaceutical firms, with 29 percent held by the Shanghai State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC).

This structure underpins what DEA experts like Im argue: that major figures such as Zhenli Ye Gon—and, even more so, his Chinese Canadian counterpart Tse Chi Lop—serve as “command and control” for the Western Hemisphere’s fentanyl and money laundering networks. Their global narco empires, Im says, operate with the knowledge, protection, and involvement—sometimes directly—of senior Chinese Communist Party officials.

The staggering scale of these synthetic narco empires—decentralized across North America, yet rooted in state-directed chemical output from Communist Party-controlled or Party-influenced firms such as Chifeng—is reflected in the DEA affidavit that led to Ye Gon’s conviction.

When Mexican prosecutors raided his Mexico City residence in 2007, they found $205.5 million in U.S. cash stacked in suitcases, closets, and false compartments. Another $2 million in foreign currency and traveler’s checks was seized along with luxury goods, high-end jewelry, and receipts from Las Vegas casinos. Federal agents also confiscated seven firearms, including a fully automatic AK-47.

Equally disturbing was a handwritten note found among Ye Gon’s seized records. “Due to the detention of the flour, my associates and I had some problems,” it read. “I have contact with customs. Call me to work.” Investigators interpreted “flour” as code for a seized chemical shipment, and “books” as shorthand for drug proceeds. The reference to “contact with customs” pointed to a corrupt facilitator within Mexico’s border control system—an insider positioned to keep the chemical pipeline open. For veteran DEA agents, it was a textbook indicator of entrenched, systemic corruption.

Federal agents later executed a search warrant at UNIMED’s corporate headquarters in Mexico City. There, they discovered an additional $111,000 in cash, along with records for bank accounts in the United States, China, and Hong Kong. Wire transfer receipts and confirmation pages linked UNIMED to Mexican currency exchanges, detailing the flow of funds from Mexico into accounts across the United States and Europe.

“From a law enforcement standpoint,” the affidavit stated, “these casas de cambio have been widely used by drug trafficking organizations in Mexico and South America to insert their illegal drug proceeds into the legitimate world financial systems in an attempt to disguise the origin of the money and launder its criminal history.”

The DEA affidavit reads like an early blueprint—one that foreshadowed the global expansion of Chinese money laundering and chemical dominance over synthetic drug production.

It documents how, by 2004, escalating U.S. enforcement and tighter international controls on precursors like pseudoephedrine forced methamphetamine production out of the United States and into Mexico. By 2006, Mexican authorities had seized what were then the two largest meth labs in the Western Hemisphere. These industrial-scale operations were directly linked to trafficking routes into the United States and supplied by Chinese precursor chemicals. They marked the emergence of a decentralized manufacturing model—one that has since migrated north and now operates inside Canada.

The affidavit also provides forensic insight into how, beginning in the early 2000s, Chinese state-linked traffickers assumed control over global money laundering for ultra-violent Latin American cartels.

While Ye Gon’s reputation as a high-rolling gambler—losing at least $125 million in Las Vegas casinos between 2004 and 2007—is well documented, what appears to have gone unreported is that the DEA’s Las Vegas field office obtained intelligence directly tying his casino activity to laundering operations for a major Mexican drug cartel.

“A Mexican organized crime group began blackmailing YE GON in México,” stated an affidavit by DEA Special Agent Eduardo A. Chávez. “According to YE GON, the group wanted to store cash at YE GON’s residence in México City. In addition to storing cash, the group wanted YE GON to launder their money. YE GON told the source that he knew the money in his house was ‘dirty money’ and the proceeds of narcotics trafficking. YE GON told the source that he continually received threats against himself and his family, so he believed that he had no choice but to launder the money. YE GON told the source that the traffickers instructed him to use his bank accounts to send the money to Las Vegas, where he could launder it.”

It’s just one vivid example of the deep integration between Chinese money launderers and Mexican cartels. While the cartels clearly operate with a brutality that commands respect—and sometimes fear—from their Chinese partners, ultimately, it is the Chinese networks that reign supreme: they control the finance, the chemicals, and the decentralized factory components underpinning the global trade. As Ye Gon’s case indicates, they sit at commanding heights.

Target the Enablers or Lose the War

The case documented a tectonic shift: the outsourcing of cartel financial operations to Chinese actors—and a new era of synthetic narco-capitalism governed not by territorial control, but by logistical mastery.

DEA agents tracking that shift—the transfer of global laundering and chemical command to China—soon formalized their findings within a strategic U.S. intelligence framework. While Don Im was leading DEA financial operations in New York, the U.S. government launched an initiative known as Linkage, designed to map the evolving East Asian narcotics supply architecture. The strategy identified how Chinese and Southeast Asian syndicates operated like a chain of interlocking specialists in chemical production, international transport, and financial laundering.

“Linkage was an initiative to identify the entire supply chain from the United States back into Southeast Asia,” Im recalled. “They called it Linkage because the way Chinese and other Asian traffickers were operating was like a chain: independent manufacturers, independent transporters, independent distributors—all linked. They didn’t work for one another, they worked with one another, relying on their specialties—production, transportation, smuggling, distribution.”

The other side of the counter-narcotics effort was the Linear Initiative, which attacked the supply chain flowing from Bolivia, Peru, and Colombia into the U.S. Today, those organizations outsource laundering to Chinese brokers—who need the cash, while the cartels need access to their polydrug profits in North America, Europe, and Australia.

This led directly to one of the most controversial cases of the era: HSBC.

Operation Royal Flush—an extension of both Linkage and Linear—targeted the financial backbone of these networks by tracing dirty cash upstream to their command centers.

“We targeted a South American bank and ended up identifying HSBC as essentially just blatantly violating anti-money laundering laws, rules, and regulations,” Im said. “We realized they were helping facilitate not just Mexican cartels, but South American cartels, Russian organized crime, Chinese organized crime, Italian organized crime—all throughout the world. And they just got a slap on the wrist: a $1.9 billion fine.”

The case continues to reverberate inside the DEA—especially after agents watched with disbelief as Canadian authorities recently imposed just a $9 million fine on TD Bank, despite mounting evidence of large-scale fentanyl money laundering through its North American branches, orchestrated from Toronto. For years, the activity appeared to proceed largely unchecked, even as Canadian police and senior political officials were warned of systemic vulnerabilities by the country’s financial intelligence agency, FINTRAC. Only after DEA investigators, working through the U.S. Department of Justice, advanced a sweeping probe did the true scale of the operation begin to surface.

According to sources including former U.S. State Department investigator David Asher, the case involved Chinese international students and underground bankers funneling drug cash into bank branches across the Tri-State area. Investigators traced “command and control” links to the Triad syndicate led by Tse Chi Lop—an empire rooted in Toronto and Vancouver, with longstanding ties to the Chinese Communist Party and direct links to precursor chemical factories that generate GDP for Beijing.

This brings Don Im’s most troubling observations into sharp focus—particularly Ottawa’s handling of the TD Bank case, and his deeper concern that the only effective way to confront fentanyl trafficking is to follow the money all the way to the top of political and corporate power. But that, he reiterates, is also the path into politically “inconvenient” territory.

In many ways, Im believes, following the money to the highest levels of Western enablers—once so effective in dismantling Pablo Escobar’s empire—has become a lost art. And one, he argues, that must be revived.

What he now calls for is a no-holds-barred international campaign—led by informed citizens and coordinated governments—from Vancouver to West Virginia.

“These same cartels, brokers, and Chinese precursor suppliers behind the fentanyl crisis in North America are also pushing cocaine, heroin, and meth in Europe and Australia—and Canada,” Im said.

The DEA must expand its global presence, Im argues, and embed sources deep inside the very organizations responsible for poisoning the West.

“And the nonsense view that only fentanyl should be targeted is absolutely mind-boggling,” he said. “Profits from heroin, cocaine, methamphetamine are used to produce fentanyl.”

For Im, the stakes are no longer merely criminal—they are existential. The West, he believes, is locked in an asymmetric conflict with Beijing.

“The Chinese Communist Party at all levels has been aware of the magnitude of global drug trafficking and, specifically, the cheap and easily available liquid capital and cash that can be purchased, bartered, converted, invested for any beneficial CCP-sponsored initiative—directly or indirectly—and satisfies elements of corruption at every level,” Im told The Bureau. “This is in line with the 100-year vision to expand their influence—not to destroy the West but to plunder and exploit the wealth, technology, and abundant liquid capital from the massive drug trade in North American and European consumer cities for their benefit.”

Next in this series: Narco-Funded Belt and Road

The Bureau is a reader-supported publication.

To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Editor’s Note: Don Im shares this message in conjunction with The Bureau’s ongoing investigative series, which aims to inform international policy responses to the Chinese Communist Party’s role in facilitating a hybrid fentanyl war.

“I followed and worked with many incredible agents, task force members, and intelligence analysts from the DEA, FBI, legacy U.S. Customs, IRS, RCMP, and DOJ prosecutors—professionals who dedicated their lives to combatting Asian organized crime. These unsung heroes risked their lives. Two DEA Special Agents—Paul Seema and George Montoya—gave their lives in 1988, and DEA Special Agent Jose Martinez was wounded in this war. Their dedication, efforts, and impact live on in the criminal data systems of the various agencies.”

Invite your friends and earn rewards

Crime

Letter Shows Biden Administration Privately Warned B.C. on Fentanyl Threat Years Before Patel’s Public Bombshells

Fentanyl super lab busted in BC

In recent interviews with Joe Rogan and Fox News, FBI Director Kash Patel alleged that Vancouver has become a global hub for fentanyl production and export—part of a transnational network linking Chinese Communist Party-associated suppliers and Mexican drug cartels, and exploiting systemic weaknesses in Canada’s border enforcement. “What they’re doing now … is they’re shipping that stuff not straight [into the United States],” Patel told Rogan, citing classified intelligence. “They’re having the Mexican cartels now make this fentanyl down in Mexico still, but instead of going right up the southern border and into America, they’re flying it into Vancouver. They’re taking the precursors up to Canada, manufacturing it up there, and doing their global distribution routes from up there because we’ve been so effective down south.”

His comments prompted a public response from B.C. Premier David Eby’s top cop, Solicitor General Garry Begg, who disputed the scale of the allegations.

Controversially, Patel also asserted that Washington believes Beijing is intentionally targeting the United States with fentanyl to harm younger generations—especially for strategic purposes.

But a diplomatic letter obtained exclusively by The Bureau supports the view that high-level U.S. concerns—nearly identical to Patel’s—were privately raised by U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken two years earlier.

The Blinken letter suggests that these concerns were already being voiced at the highest levels of U.S. diplomacy and intelligence in 2023—under a Democratic administration—which counters a widespread misperception in Canadian political and media spheres that the Trump administration has distorted facts about Vancouver’s role in global fentanyl trafficking logistics.

In a letter dated May 25, 2023, U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken wrote to Port Coquitlam Mayor Brad West, thanking him for participating in a fentanyl-focused roundtable at the Cities Summit of the Americas in Denver. According to West, only several mayors were invited to discuss the FBI’s strategic focus on transnational organized crime and fentanyl trafficking—an indication of the summit’s targeted focus on British Columbia. “Thank you for discussing your city’s experiences with synthetic opioids and providing valuable lessons learned we can share throughout the region,” Blinken wrote.

The letter suggested U.S. officials were not only increasingly seeing Canadian municipalities as critical partners in a hemispheric fight against synthetic drug trafficking, but viewed Mayor West as a trusted partner in British Columbia.

West told The Bureau that Blinken privately expressed the same controversial and jarring assessment that Patel later made publicly—essentially arguing that the U.S. government had assessed that China is intentionally weaponizing fentanyl against North America, and that Chinese Communist Party-linked networks are strategically operating in concert with Latin cartels.

According to The Bureau’s reporting, Blinken described growing frustration among U.S. federal agencies over Canada’s legal and enforcement deficiencies. He pointed to what American officials saw as systemic obstacles in Canadian law that made it difficult to act on intelligence involving fentanyl production, chemical precursor shipments, and laundering operations tied to cartel and CCP-linked actors.

West told The Bureau that the U.S. government was alarmed that a major money laundering investigation in British Columbia—targeting the notorious Sam Gor synthetic narcotics syndicate, which collaborates with Mexican cartels in Western Hemisphere fentanyl trafficking and money laundering, according to U.S. experts—had collapsed in Canadian court proceedings. The Bureau has confirmed with a Canadian police veteran that this investigation originated from U.S. government intelligence.

West, a vocal critic of Canada’s handling of transnational organized crime, said U.S. agencies had begun withholding sensitive intelligence, citing a lack of confidence in Canada’s ability—or willingness—to act on it.

Blinken also framed the crisis in a broader hemispheric context, noting that while national leaders met at the Ninth Summit of the Americas in Los Angeles to address the shared challenges facing the region, it was city leaders who served at the forefront of tackling those threats.

Patel’s recent public statements—which singled out Vancouver as a production hub and described air and sea trafficking routes into the U.S.—have revived the debate around Canada’s role in the opioid crisis. U.S. experts, such as former senior DEA investigator Donald Im, argue that northern border seizure statistics do not capture the majority of fentanyl activity emanating from Canada as monitored by U.S. law enforcement.

Im cited, for example, the case of Arden McCann, a Montreal man indicted in the Northern District of Georgia and accused of mailing synthetic opioids—including fentanyl, carfentanil, U-47700, and furanyl fentanyl—from Canada and China into the United States. According to the indictment, McCann—also known as “The Mailman” and “Dr. Xanax”—trafficked quantities capable of causing mass casualty events. He was later sentenced to 30 years in federal prison for operating a dark web narcotics network that, between 2015 and 2020, distributed fentanyl to 49 states and generated more than $10 million in revenue.

As part of that investigation, the DEA reported that Canadian authorities seized approximately two million counterfeit Xanax pills, five pill presses, alprazolam powder, 3,000 MDMA pills, more than $200,000 in cash, 15 firearms, ballistic vests, and detailed drug ledgers. The ledgers showed that McCann and his co-conspirators purchased alprazolam from suppliers in China, pressed the powder into counterfeit Xanax pills, and sold the product to U.S. buyers via dark web marketplaces.

-

Crime18 hours ago

Crime18 hours agoHow Chinese State-Linked Networks Replaced the Medellín Model with Global Logistics and Political Protection

-

Addictions19 hours ago

Addictions19 hours agoNew RCMP program steering opioid addicted towards treatment and recovery

-

Aristotle Foundation20 hours ago

Aristotle Foundation20 hours agoWe need an immigration policy that will serve all Canadians

-

Business17 hours ago

Business17 hours agoNatural gas pipeline ownership spreads across 36 First Nations in B.C.

-

Courageous Discourse15 hours ago

Courageous Discourse15 hours agoHealthcare Blockbuster – RFK Jr removes all 17 members of CDC Vaccine Advisory Panel!

-

Health11 hours ago

Health11 hours agoRFK Jr. purges CDC vaccine panel, citing decades of ‘skewed science’

-

Censorship Industrial Complex14 hours ago

Censorship Industrial Complex14 hours agoAlberta senator wants to revive lapsed Trudeau internet censorship bill

-

Crime21 hours ago

Crime21 hours agoLetter Shows Biden Administration Privately Warned B.C. on Fentanyl Threat Years Before Patel’s Public Bombshells