Alberta

This is how a Local Musician is giving back to her Community

Kate Stevens is a local Calgarian and Bishop Carroll High School Alumni making a splash in the Canadian music industry with her original music and community investment initiatives. A talented singer-songwriter, she plays the ukulele, piano and guitar and writes all of her own music.

Growing up in a musical household, Kate’s passion for music began at an early age and stayed with her all through her school years, eventually landing her in the music program at Bishop Carroll High School in Southwest Calgary. The education structure at BCHS allowed Kate to focus strongly on her love of music and develop as a young artist, impressively recording an entire studio album during her senior year. She also sang in choir and vocal jazz groups, building lasting connections within her high school and across the Calgary music community.

Just 20 years old, Kate graduated from BCHS in 2017, the same year she released her debut EP, Handmade Rumors. Since graduation, things have been crazy for Kate. From bringing home YYC Music Awards Female Artist of the Year in 2018 to 4 nominations at the 2019 YYC Music Awards, releasing another single and launching the Youth Musicians of Music Mile Alliance (YOMOMMA) to help nurture young musicians in Calgary, busy is an understatement. However, despite her exciting rise and packed schedule, Kate remains deeply invested in her community, and recently launched a new initiative to give back to the BCHS program that helped her get her own start. Using funds from a recent licensing agreement for one of her songs, she has elected to sponsor an annual scholarship for a BCHS vocal student in their final year.

“I was lucky to attend Bishop Carroll High School, “says Kate, “the incredible music program there helped me to develop as an artist, and I would like to give financial support to future musicians.” At $250 dollars a year, the scholarship will be awarded by the BCHS Choir Director to a student who shows exemplary leadership skills and wants to pursue music after graduation. Having been on the receiving end of scholarships throughout her own high school career, Kate is aware of the positive impact these types of grants can have on the lives of developing youth, and wanted to be a part of the process that helps young musicians chase their dreams. “If I can support someone in this industry and really encourage the idea that music is important, then I’ve done my job.”

Currently, all of Kate’s upcoming performances have been cancelled as a result of COVID-19. Although she misses interacting with crowds and performing on stage, she remains optimistic and excited for the future. To hear her music and read more about her story, visit https://www.katestevensmusic.com.

Check out WeMaple video in partnership with Calgary Arts Development featuring Kate Stevens here.

For more stories, visit Todayville Calgary.

Alberta

COWBOY UP! Pierre Poilievre Promises to Fight for Oil and Gas, a Stronger Military and the Interests of Western Canada

Fr0m Energy Now

As Calgarians take a break from the incessant news of tariff threat deadlines and global economic challenges to celebrate the annual Stampede, Conservative party leader Pierre Poilievre gave them even more to celebrate.

Poilievre returned to Calgary, his hometown, to outline his plan to amplify the legitimate demands of Western Canada and not only fight for oil and gas, but also fight for the interests of farmers, for low taxes, for decentralization, a stronger military and a smaller federal government.

Speaking at the annual Conservative party BBQ at Heritage Park in Calgary (a place Poilievre often visited on school trips growing up), he was reminded of the challenges his family experienced during the years when Trudeau senior was Prime Minister and the disastrous effect of his economic policies.

“I was born in ’79,” Poilievre said. “and only a few years later, Pierre Elliott Trudeau would attack our province with the National Energy Program. There are still a few that remember it. At the same time, he hammered the entire country with money printing deficits that gave us the worst inflation and interest rates in our history. Our family actually lost our home, and we had to scrimp and save and get help from extended family in order to get our little place in Shaughnessy, which my mother still lives in.”

This very personal story resonated with many in the crowd who are now experiencing an affordability crisis that leaves families struggling and young adults unable to afford their first house or condo. Poilievre said that the experience was a powerful motivator for his entry into politics. He wasted no time in proposing a solution – build alliances with other provinces with mutual interests, and he emphasized the importance of advocating for provincial needs.

“Let’s build an alliance with British Columbians who want to ship liquefied natural gas out of the Pacific Coast to Asia, and with Saskatchewanians, Newfoundlanders and Labradorians who want to develop their oil and gas and aren’t interested in having anyone in Ottawa cap how much they can produce. Let’s build alliances with Manitobans who want to ship oil in the port of Churchill… with Quebec and other provinces that want to decentralize our country and get Ottawa out of our business so that provinces and people can make their own decisions.”

Poilievre heavily criticized the federal government’s spending and policies of the last decade, including the increase in government costs, and he highlighted the negative impact of those policies on economic stability and warned of the dangers of high inflation and debt. He advocated strongly for a free-market economy, advocating for less government intervention, where businesses compete to impress customers rather than impress politicians. He also addressed the decade-long practice of blocking and then subsidizing certain industries. Poilievre referred to a famous quote from Ronald Reagan as the modus operandi of the current federal regime.

“The Government’s view of the economy could be summed up in a few short phrases. If anything moves, tax it. If it keeps moving, regulate it. And if it stops moving, subsidize it.”

The practice of blocking and then subsidizing is merely a ploy to grab power, according to Poilievre, making industry far too reliant on government control.

“By blocking you from doing something and then making you ask the government to help you do it, it makes you reliant. It puts them at the center of all power, and that is their mission…a full government takeover of our economy. There’s a core difference between an economy controlled by the government and one controlled by the free market. Businesses have to clamour to please politicians and bureaucrats. In a free market (which we favour), businesses clamour to impress customers. The idea is to put people in charge of their economic lives by letting them have free exchange of work for wages, product for payment and investment for interest.”

Poilievre also said he plans to oppose any ban on gas-powered vehicles, saying, “You should be in the driver’s seat and have the freedom to decide.” This is in reference to the Trudeau-era plan to ban the sale of gas-powered cars by 2035, which the Carney government has said they have no intention to change, even though automakers are indicating that the targets cannot be met. He also intends to oppose the Industrial Carbon tax, Bill C-69 the Impact Assessment Act, Bill C-48 the Oil tanker ban, the proposed emissions cap which will cap energy production, as well as the single-use plastics ban and Bill C-11, also known as the Online Streaming Act and the proposed “Online Harms Act,” also known as Bill C-63. Poilievre closed with rallying thoughts that had a distinctive Western flavour.

“Fighting for these values is never easy. Change, as we’ve seen, is not easy. Nothing worth doing is easy… Making Alberta was hard. Making Canada, the country we love, was even harder. But we don’t back down, and we don’t run away. When things get hard, we dust ourselves off, we get back in the saddle, and we gallop forward to the fight.”

Cowboy up, Mr. Poilievre.

Maureen McCall is an energy professional who writes on issues affecting the energy industry.

Alberta

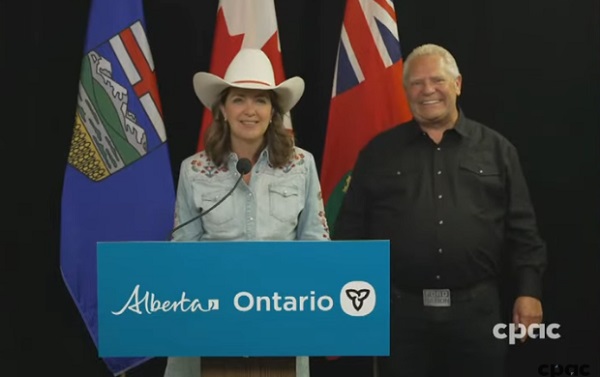

Alberta and Ontario sign agreements to drive oil and gas pipelines, energy corridors, and repeal investment blocking federal policies

Alberta-Ontario MOUs fuel more pipelines and trade

Alberta Premier Danielle Smith and Ontario Premier Doug Ford have signed two memorandums of understanding (MOUs) during Premier Ford’s visit to the Calgary Stampede, outlining their commitment to strengthen interprovincial trade, drive major infrastructure development, and grow Canada’s global competitiveness by building new pipelines, rail lines and other energy and trade infrastructure.

The two provinces agree on the need for the federal government to address the underlying conditions that have harmed the energy industry in Canada. This includes significantly amending or repealing the Impact Assessment Act, as well as repealing the Oil Tanker Moratorium Act, Clean Electricity Regulations, the Oil and Gas Sector Greenhouse Gas Emissions Cap, and all other federal initiatives that discriminately impact the energy sector, as well as sectors such as mining and manufacturing. Taking action will ensure Alberta and Ontario can attract the investment and project partners needed to get shovels in the ground, grow industries and create jobs.

The first MOU focuses on developing strategic trade corridors and energy infrastructure to connect Alberta and Ontario’s oil, gas and critical minerals to global markets. This includes support for new oil and gas pipeline projects, enhanced rail and port infrastructure at sites in James Bay and southern Ontario, as well as end-to-end supply chain development for refining and processing of Alberta’s energy exports. The two provinces will also collaborate on nuclear energy development to help meet growing electricity demands while ensuring reliable and affordable power.

The second MOU outlines Alberta’s commitment to explore prioritizing made-in-Canada vehicle purchases for its government fleet. It also includes a joint commitment to reduce barriers and improve the interprovincial trade of liquor products.

“Alberta and Ontario are joining forces to get shovels in the ground and resources to market. These MOUs are about building pipelines and boosting trade that connects Canadian energy and products to the world, while advocating for the right conditions to get it done. Government must get out of the way, partner with industry and support the projects this country needs to grow. I look forward to working with Premier Doug Ford to unleash the full potential of our economy and build the future that people across Alberta and across the country have been waiting far too long for.”

“In the face of President Trump’s tariffs and ongoing economic uncertainty, Canadians need to work together to build the infrastructure that will diversify our trading partners and end our dependence on the United States. By building pipelines, rail lines and the energy and trade infrastructure that connects our country, we will build a more competitive, more resilient and more self-reliant economy and country. Together, we are building the infrastructure we need to protect Canada, our workers, businesses and communities. Let’s build Canada.”

These agreements build on Alberta and Ontario’s shared commitment to free enterprise, economic growth and nation-building. The provinces will continue engaging with Indigenous partners, industry and other governments to move key projects forward.

“Never before has it been more important for Canada to unite on developing energy infrastructure. Alberta’s oil, natural gas, and know-how will allow Canada to be an energy superpower and that will make all Canadians more prosperous. To do so, we need to continue these important energy infrastructure discussions and have more agreements like this one with Ontario.”

“These MOUs with Ontario build on the work Alberta has already done with Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Northwest Territories and the Port of Prince Rupert. We’re proving that by working together, we can get pipelines built, open new rail and port routes, and break down the barriers that hold back opportunities in Canada.”

“Canada’s economy has an opportunity to become stronger thanks to leadership and steps taken by provincial governments like Alberta and Ontario. Removing interprovincial trade barriers, increasing labour mobility and attracting investment are absolutely crucial to Canada’s future economic prosperity.”

Together, Alberta and Ontario are demonstrating the shared benefits and opportunities that result from collaborative partnerships, and what it takes to keep Canada competitive in a changing world.

Quick facts

- Steering committees with Alberta and Ontario government officials will be struck to facilitate work and cooperation under the agreements.

- Alberta and Ontario will work collaboratively to launch a preliminary joint feasibility study in 2025 to help move private sector led investments in rail, pipeline(s) and port(s) projects forward.

- These latest agreements follow an earlier MOU Premiers Danielle Smith and Doug Ford signed on June 1, 2025, to open up trade between the provinces and advance shared priorities within the Canadian federation.

Related information

-

Alberta2 days ago

Alberta2 days agoAlberta Next: Immigration

-

Alberta Sports Hall of Fame and Museum1 day ago

Alberta Sports Hall of Fame and Museum1 day agoAlberta Sports Hall of Fame 2025 Inductee Profiles – Para Nordic Skiing – Brian and Robin McKeever

-

Crime1 day ago

Crime1 day agoNews Jeffrey Epstein did not have a client list, nor did he kill himself, Trump DOJ, FBI claim

-

COVID-1924 hours ago

COVID-1924 hours agoFDA requires new warning on mRNA COVID shots due to heart damage in young men

-

Business22 hours ago

Business22 hours agoCarney’s new agenda faces old Canadian problems

-

Daily Caller10 hours ago

Daily Caller10 hours agoBlackouts Coming If America Continues With Biden-Era Green Frenzy, Trump Admin Warns

-

Indigenous22 hours ago

Indigenous22 hours agoInternal emails show Canadian gov’t doubted ‘mass graves’ narrative but went along with it

-

Bruce Dowbiggin22 hours ago

Bruce Dowbiggin22 hours agoEau Canada! Join Us In An Inclusive New National Anthem