Community

My European Favourites – Canada in WWI Belgium

My European Favourites – Canada in WWI Belgium

My European Favourites – Canada in WWI Belgium

We have conducted many tours to Europe since 1994, and many people we meet are very grateful for the role and sacrifice Canadians made in both World Wars. This is especially true in the Netherlands, Belgium and France. Canada has a proud history of stepping up and bravely serving to preserve peace and freedom; this is especially true during the First World War. When Britain went to war in 1914, members of the British Empire, including Canada, automatically entered the war. Canadian troops were at the forefront of many of the greatest battles, endured heavy casualties, and often persevered to overcome the enemy in seemingly impossible conditions. Over 650,000 men and women from our country served in uniform during the Great War, and it is said that Canada became a nation during the First World War. The Ypres Salient in western Belgium was the site of many of WWI’s deadliest battles, and it is the focal point of our sobering tour of Canada in WWI.

Bruges Veterans parade on Nov. 11, a canal cruise and colorful buildings on Market square.

Bruges

Bruges, the capital of West Flanders with just over 100,000 residents, is the starting point for our tour. Bruges is known for its historic city centre, medieval buildings, cobblestone streets, and canals. From the 12th to the 15th century, Bruges’ location, on a waterway called the “Golden Inlet,” made it a perfect location for merchants, and soon it became a member of the Hanseatic League which controlled trade from the Baltic and North Seas. This access to the English Channel became of paramount importance during WWI. A couple of years ago, we were lucky enough to be in Bruges on the November 11th Armistice Day, and we saw a Veterans parade make its way through the market square.

The Passchendaele Canadian Memorial with wreaths and photos placed on Armistice Day.

Passchendaele Canadian Memorial

Only forty kilometers from Bruges is the Canadian War memorial at Passchendaele. Fought from July 31 to November 10, 1917, the Battle of Passchendaele, also known as the Third Battle of Ypres, was fought to gain control of Belgium’s important channel ports. The Ypres Salient was the last portion of Belgium that was not under control of the Germans, and after three years of fierce fighting, allied forces from Britain, Australia and New Zealand were deadlocked with the Germans. The area was flat and was kept dry only by a drainage system of dykes and ditches; however three years of fighting had destroyed much of the drainage infrastructure. With no drainage and heavy rains in the fall of 1917, the numerous shell craters filled with water, and the battlefield became a muddy bog strewn with fallen trees, metal shell remnants and dead soldiers.

In mid-October, and after their April success at Vimy Ridge in France, four divisions of the Canadian forces arrived at Passchendaele to relieve the Allies. The 20,000 Canadians were brought in to assist in the final push to capture the ridge and were shocked at the horrible conditions. Under commander Sir Arthur Currie, the Canadian forces immediately began preparations, and with a late October offensive assisted by two British divisions, they eventually captured the ridge on the 6th of November. When the fighting ended four days later, Canadians had 16,000 casualties with 4000 killed and an approximately 12,000 wounded.

Unfortunately, the effort did not do much to help the Allied effort and the battle became synonymous with the senseless loss of life in the First World War. In total, the British forces suffered an estimated 275,000 casualties, while the Germans had 220,00 in just this one battle.

The Passchendaele Canadian Memorial is located at the site of the Crest Farm where some of the fiercest fighting during the battle took place. The monument’s location is surrounded by a grove of maple trees overlooking the Ravebeek valley. At the centre of the memorial, there is a huge block of octagonal granite with carved ornamental maple leaves and the following text:

THE CANADIAN CORPS IN OCT.- NOV. 1917 ADVANCED ACROSS THIS VALLEY – THEN A TREACHEROUS MORASS – CAPTURED AND HELD THE PASSCHENDAELE RIDGE

A nearby plaque explains the historic significance of the site for Canadians. The remarkable efforts of these brave Canadians in unbelievably bad conditions should never be forgotten. Nine exceptional Canadians earned the highest award for military valour, the Victoria Cross, for their bravery at Passchendaele.

The “Brooding Soldier” of the St. Julien Canadian Monument

St. Julien Canadian Memorial

Only a few kilometers from the Passchendaele Canadian Memorial, on the main road from Bruges to Ypres, we find one of Canada’s most striking memorials near the village of Saint-Julien, Langemark-Poelkapelle. The towering St. Julien Canadian Memorial is visible well before arriving at the site. It commemorates those who perished from the First Canadian Infantry Division during the Second Battle of Ypres. On April 22, 1915, the Germans unleashed the first poison gas attacks of the First World War using chlorine gas cylinders. In the face of chemical warfare for 48 hours, the Canadians held the line and prevented a German breakthrough until reinforcements arrived. During those 48 hours, the 18,000 strong First Canadian Infantry Division suffered over 6,000 casualties, of which 2,000 were killed.

During the war, the location of the memorial was known as Vancouver corner. The monument’s eleven meter tall granite column is topped with the upper torso of a “Brooding Soldier.” The soldier’s helmeted head is bowed and his arms folded on the butt end of his, reversed and down-turned, rifle. The sentinel’s striking pose is a gesture of mourning and respect for the fallen. His bowed head faces the direction from which the gas attack came.

The monument sits on a circular terrace surrounded by conifer trees and juniper bushes brought here from Canada. Some of the garden soil was brought from different parts of Canada to acknowledge that members from throughout the country served valiantly on this ground. A plaque on the side of the monument reads:

THIS COLUMN MARKS THE BATTLEFIELD WHERE 18,000 CANADIANS ON THE BRITISH LEFT WITHSTOOD THE FIRST GERMAN GAS ATTACKS THE 22-24 APRIL 1915. 2000 FELL AND LIE BURIED NEARBY

The Brooding Soldier is one of the most impactful war memorials I have seen in Europe. The designer of the memorial was able to effectively transfer the emotions of the soldier to the visitor. I have seen more than one tear shed at the memorial on our tours as people reflected on the horror that must have gripped each Canadian soldier as he was faced with deadly chemical warfare.

Before leaving, take a moment to read the plaque across the street for Lieutenant Edward Donald Bellew, who became the first Canadian officer to be awarded the Victoria Cross for his acts of bravery during the gas attack on 24 April, 1915.

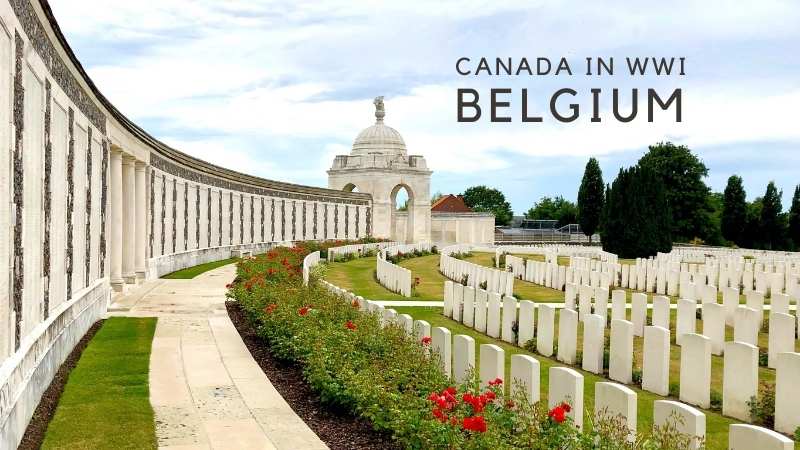

Panoramic view of the Tyne Cot Cemetery.

Tyne Cot Cemetery

Only minutes from the St. Julien Canadian Monument, we reach the Tyne Cot Cemetery. Tyne Cot is the largest Commonwealth war cemetery in the world with the remains of 11,961 Commonwealth soldiers from the First World War. The cemetery commenced in October 1917 with over 300 graves marked by wooden crosses. After the war, the crosses were replaced by headstones and the cemetery was enlarged by concentrating graves from other nearby battlefields and cemeteries. About 70% of the headstones are for unknown soldiers who could not be identified and may be listed on the Memorial Wall.

Tyne Cot Memorial, Canadian headstones and a British police group laying a wreath.

A curve shaped Memorial Wall, located at the rear of the cemetery, displays names of 34,991 men with no known grave who died on August 16th, 1917 and onwards. Their names on the wall panels are arranged by regiment and rank. Those who died previous to August 16th are engraved on the Menin Gate in Ypres.

The cemetery site overlooks the surrounding area, and as such, was strategically important. You can still see remains of German pill boxes on the cemetery grounds, and a centrally placed “Cross of Sacrifice” was built on top of one of the pill boxes.

Grave of Victoria Cross recipient Private Robertson, rows of headstones, and poppy wreaths.

There are 966 Canadian soldiers buried at Tyne Cot including Private James Peter Robertson (1883-1917), who was awarded the Victoria Cross for bravery. Private Robertson was born in Pictou County, Nova Scotia but lived the majority of his life in Medicine Hat, Alberta. Many Canadians stopping at the cemetery will search out his headstone in particular.

Walking past the row upon row of gravestones and seeing all the names on the Memorial is overwhelming, sobering and humbling. Even more moving to think that the over 40,000 that are buried or listed on the wall at Tyne Cot are only a fraction of the over 250,000 Allied casualties at the battles of Ypres.

Wreaths laid for Armistice Day, the cemetery and the bunkers.

Essex Farm Cemetery

Just down the road, we stop at a much smaller cemetery than Tyne Cot, but it’s one with great significance for Canadians. As a school child, Remembrance Day meant reading the poem “In Flanders Fields” by Lieutenant-Colonel John McCrae and drawing images of the Flanders Fields he describes with crosses and poppies. In fact, I can’t think of a Remebrance Day when I haven’t heard or read the poem. It’s a poem that has become a symbol of Canadian valour and our national identity.

In Flanders fields the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below.

We are the Dead. Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie,

In Flanders fields.

Take up our quarrel with the foe:

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high.

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders fields.

John McCrae, from Guelph, Ontario, worked at various hospitals as a physician and was a member of the Royal College of Surgeons. He served as a Canadian Contingent soldier in the South African Boer War from 1899-1900 and reenlisted after the start of World War I.

He worked at a Field Dressing Station for 17 days during the Second Battle of Ypres starting in late April, 1915. Here, he tirelessly and in terrible conditions, tended to the sick and wounded. On May 3, 1915 after the death of close friend Lt. Alexis Helmer and his subsequent burial amongst the poppies, he wrote the famous poem. The poem was later published in a British magazine and its popularity led to the poppy being adopted as the symbol of remembrance for not only Canadian but for British and Commonwealth fallen soldiers.

Lieutenant-Colonel John McCrae was, later that year, transferred to a hospital in Boulogne, France, where he worked until his death from pneumonia on January of 1918.

At the Essex Farm Cemetery, we can enter the bunkers that were used as a dressing station during the war. There is also a Canadian government plaque in honour of John McCrae which includes the text of the famous poem. There are 1,206 servicemen buried in the cemetery, and one of the most visited is the grave of 15 year old British Rifleman Valentine Joe Strudwick. Even though the official age of army recruits was 19, some young men lied about their age when they enlisted. Just before his 15th birthday on February 14, 1915, he enlisted in the 8Th Battalion Rifle Brigade and was killed 11 months later on January 14, 1916.

The Menin Gate, the Ypres War Victims Monument and the reconstructed Cloth Hall.

Ypres (Ieper in Dutch)

A short distance from the Essex Farm Cemetery is the town of Ypres that was flattened during the First World War. When we arrive to the city centre, we immediately see the large medieval Cloth Hall which dominates the Market Square. It was rebuilt after the war according to the original plans from 1304, and as the name implies, it originally served as the main market and warehouse for the local cloth industry. Today, the building houses the “In Flanders Fields Museum

‘ and information centre. The museum contains many objects and images from the battles in the West Flanders region and tells the story of the First World War in Belgium. If possible, I urge visitors to climb the 231 steps up the Cloth Hall’s belfry to get a panoramic view of the city and the surrounding battlefields.

The Menin Gate, located a short distance from the Cloth Hall, contains the names of almost 55,000 soldiers who died prior to August 16, 1917 and were never identified or found. When not all the names of missing soldiers could be placed on the gate, those who died after August 16, 1917 were placed on the Wall Memorial at the Tyne Cot Cemetery. There are 6,983 Canadians on the Menin Gate including three Victoria Cross recipients; Frederick Fisher, Frederick William Hall and Hugh McDonald McKenzie. Private John Smith of the 14th Battalion Canadian Infantry who died at just 15 years of age is also listed on the gate.

The gate is located on the spot where soldiers would leave the town to go fight on the frontline. A group of dedicated volunteers honour the soldiers’ who died in the three battles of the Ypres Salient between 1914 and 1918 with Last Post ceremony. No matter the weather, the ceremony has occurred every evening at 8 p.m. since 1928, except for a four year pause during WWII when the town was under German occupation. Police will stop traffic and a crowd will gather to hear the buglers sound the last post. The buglers are all members of the local volunteer fire department and wear their uniform during the ceremony. If you get the opportunity, please take in the very moving Last Post ceremony.

Poppies in Flanders fields.

Other Memorials in the Ypres Salient in Belgium

On our day tour, it is impossible to visit all the important battlefields and Canadian Monuments in the area. Other places you may want to visit include the Hill 62 (Sanctuary Wood) Memorial, the Princess Patricia’s Light Infantry Memorial, the Passchendaele New British Cemetery, and the Memorial Museum Passchendaele 1917, but there are many others.

During this day trip from Bruges, it reinforced, to me, what it meant to be Canadian. I wish I could take every Canadian to West Flanders in Belgium, so that they can understand the bravery, heroism and sacrifice made by our finest generations who fought in two great wars.

I am very thankful that my generation has never had to endure the horrors of war and pray that our future generations do not as well.

Explore Europe With Us

Azorcan Global Sport, School and Sightseeing Tours have taken thousands to Europe on their custom group tours since 1994. Visit azorcan.net to see all our custom tour possibilities for your group of 26 or more. Individuals can join our “open” signature sport, sightseeing and sport fan tours including our popular Canada hockey fan tours to the World Juniors. At azorcan.net/media you can read our newsletters and listen to our podcasts.

Images compliments of Paul Almeida and Azorcan Tours.

Click to read more of Paul’s excellent series on Europe.

Community

Support local healthcare while winning amazing prizes!

|

|

|

|

|

|

Community

The 2025 Red Deer Hospital Lottery is here! Lower ticket prices!!

|

|

|

|

|

|

-

Brownstone Institute2 days ago

Brownstone Institute2 days agoFDA Exposed: Hundreds of Drugs Approved without Proof They Work

-

Energy1 day ago

Energy1 day agoChina undermining American energy independence, report says

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoTrump on Canada tariff deadline: ‘We can do whatever we want’

-

Automotive1 day ago

Automotive1 day agoElectric vehicle sales are falling hard in BC, and it is time to recognize reality.

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoEurope backs off greenwashing rules — Canada should take note

-

Automotive1 day ago

Automotive1 day agoPower Struggle: Electric vehicles and reality

-

Business4 hours ago

Business4 hours agoCanada Caves: Carney ditches digital services tax after criticism from Trump

-

Crime4 hours ago

Crime4 hours agoSuspected ambush leaves two firefighters dead in Idaho