Business

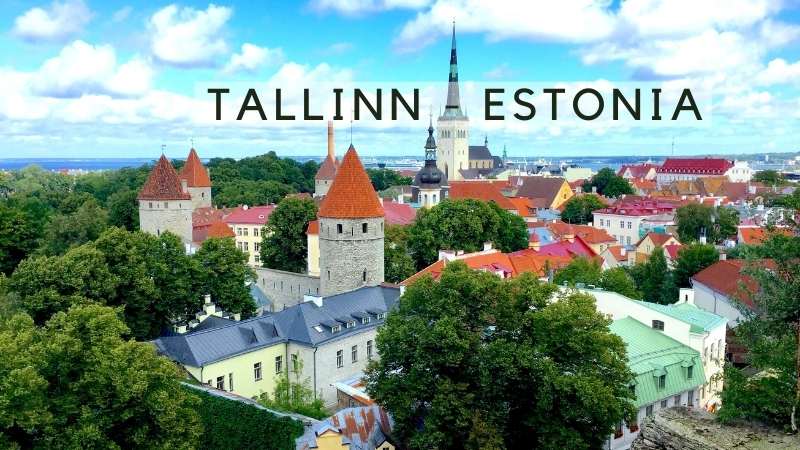

My European Favourites – Tallinn, Estonia

Tallinn is one of those cities that you never hear people talk about visiting, but once you do, it becomes an instant favourite. Whenever we do an itinerary for a hockey, ringette or sightseeing group to Sweden and Finland, I always encourage the group to add a side trip to Estonia’s capital. It is only a two hour ferry ride from Helsinki to Tallinn, so it’s perfect for a day trip.

Tallinn has just under half a million inhabitants and is the largest city of Estonia. It is located directly south of Helsinki on the Gulf of Finland and on the eastern edge of the Baltic Sea. Once known by its German name, Raval, Tallinn has one of the best preserved old towns in Europe. Unlike many towns in Europe, Tallinn’s historic old town was never destroyed by war and is listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. I like to think of it as a smaller Prague. The city started building protective walls in the 13th century, and over time, it enlarged to a defence system of over two kilometers with gates and towers. Much of these structures survive today including twenty of the pointy red roofed towers. In some areas, it is possible to walk along the walls.

Near the old town you will find traditional neighborhoods with colorful wooden houses, green spaces and the redeveloped bustling port area. Estonians are blessed with public beaches to enjoy in the summer months and nearby forests to explore on nature walks. Within view of the old town, there is a modern city, complete with skyscrapers and all the modern amenities you would expect. How modern is Tallinn? It has free public WIFI, and as a high-tech city, it has become a leader in the sector of cyber security. You may have used the services of a well-known Estonian startup company named Skype.

About Estonia

There is evidence that the area was settled as far back as 5,000 years ago, but the city became an important trading hub in the 14th to 16th centuries when it was a member of the Hanseatic League, which controlled trade in the Baltic and North Seas. Even at that time, the city only had about 8,000 inhabitants.

Over the years, Estonia has been ruled by the Holy Roman Empire, Denmark, Sweden and Russia. The country gained short lived independence from Russia after WWI only to be reclaimed as part of the Soviet Union after WWII. Like most of the countries that became part of the USSR, they suffered through a fifty year period of communist policies and stagnation. In 1991, after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Estonia regained its independence. Since then it has flourished into a western style city while maintaining its rich cultural and architectural history. It is a member of the European Union and NATO.

Tallinn’s distinctive mix of a modern and historic skyline as we arrive on the ferry from Helsinki.

Ferry to Tallinn

Tallinn is a two-hour ferry ride south from Helsinki, and it’s possible to go early in the morning across the Gulf of Finland and return late on the evening ferry. The Tallink ferry has sitting areas on different decks plus shopping and dining options onboard. If possible, I would recommend an overnight stay near the old town and return to Helsinki the following evening.

From Sweden, you can arrive on the overnight ferry that leaves Stockholm in the early evening and arrives in Tallinn in the morning. Your individual ticket includes a cabin that can sleep up to four people with two single beds and two pull down upper berths. Onboard, you can enjoy shopping, entertainment, bars and restaurants. Another option from Stockholm is to take the ferry to Riga and spend a couple of days in Latvia’s capital. The drive from Riga to Tallin is about four hours, and I usually like to stop along the way in the seaside resort city of Parnu to have lunch and walk in the city centre.

A Tale of Two Towns

Tallinn’s historic center is separated into two areas, Toompea, and Vanalinn. At one time, they were two feuding medieval towns. The upper town, Toompea, includes the aptly named Toompea Castle. The lower town, Vanalinn, has narrow alleyways, the town square, shops and restaurants. Vanalinn, was the Hanseatic League trading center filled with merchants from Germany, Denmark and Sweden. The two areas are connected by two passages called the short leg (Lühike Jalg) and the long leg (Pikk jalg).

Toompea, Tallinn’s Upper Town

As expected, the Toompea Castle sits high above the lower town on an ancient stronghold site that dates back to a wooden fortress in the 9th century. The castle, a symbol of political power through the ages, has been expanded and remodeled over the years by Estonia’s rulers to meet their needs.

Once a castle of ancient Estonians starting in the 11th century, it was later used by the Danish during most of the 13th century. It wasn’t until the 14th and 15th centuries, while in the hands of the Holy Roman Empire’s Teutonic Order, that it was built to resemble what we see today. The religious order changed the castle interior to include a chapel, chapel house, convent and dormitories for the knights. They added defence towers named Pikk Hermann (Tall Hermann), Landskrone (Crown of the land), Pilsticker (Arrow Sharpener) and Stür den Kerl (Ward Off Enemy) to protect each of its four corners. During the 16th century when Estonia became a part of Sweden, they changed the castle from a crusader’s fortress to a symbol of political power, with an administrative and ceremonial purpose.

Tall Hermann, entrance to the Governors Garden and the Toompea Castle’s pink palace.

When the Russians took over in the 18th century, the Czar had the castle turned into a palace by adding a Baroque and Neoclassical wing to the eastern part of the castle and a public park on the south east. When Estonia declared its first independence from Russia after WWI, the former convent of the Teutonic Order was transferred into an assembly hall for the Parliament of Estonia, named the Riigikogu. After being disbanded during the Soviet era from 1940 to 1991, the assembly, the Riigikogu, was reinstated in 1992 as the Estonian Parliament with 101 members.

I like to start my tour of Tallinn in the upper town just outside of the Toompea Castle, so I can get a good look at the impressive Tall Herman and original castle wall from the Governors Garden. During the castle’s evolution, the Stür den Kerl castle tower has been demolished while the others have been integrated into building projects. The 48 meter high Tall Hermann still stands and has become an important symbol of Tallinn and the nation. The Estonian flag is raised atop the tower every day at sunrise as the national anthem plays and it is lowered at sunset.

Around the corner from the park is the Lossi Plats (Castle Square) where we can see the pink palace which was added to the front of Toompea Castle during the renovations by Russian Czars. Topped by the Estonian flag, the one-time medieval fortress is now clearly the modern centre of government for Estonia. On the opposite side of the square is a richly decorated Russian orthodox cathedral.

The Castle Square, the Alexander Nevsky Cathedral and an Russian Orthodox mosaic.

Alexander Nevsky Cathedral

The striking Alexander Nevsky Cathedral was built in 1900 in Russian Revival style when Estonia was part of the Russian Empire. It is Tallinn’s largest orthodox cupola cathedral and is dedicated to Saint Alexander Nevsky, a Russian military hero, who in 1242, won a famous “Battle of the Ice” against the Teutonic Knights on Lake Peipus. The lake on Estonia’s eastern border is shared with Russia with the modern day border between the countries being about half way across.

During the USSR period, the church came into decline due to communist non-religious policies. Since 1991, the church has been meticulously restored even though it is a constant reminder of Russia’s influence, power and oppression over Estonia through the ages. There were actually plans to demolish the structure in 1924, but it was spared due to a lack of funds to raze such a large building. Today, the church is one of Tallinn’s most visited attractions and is unique due to its contrasting architectural style.

The church exterior has five onion domes, each topped with a gilded Orthodox cross. The church has eleven bells that were cast in St. Petersburg, including one massive 16 ton bell.

Like other traditional Orthodox churches, there are no pews as worshippers were required to stand during services. The ornate interior has three alters, stained glass windows and three gilded wooden iconostases (wall of icons and religious paintings) which separate the nave from the alters. Entrance to the cathedral is free. The intricate detail and colors of the mosaics and icons are amazing and well worth seeing.

St. Mary’s Church, the top of the baroque tower spire with the year 1772.

Leaving the Castle Square, we venture further into the upper town, and about 100 meters in, we reach the Kiriku Plats (Church Square) and a white medieval church with a baroque bell tower. The Toomkrik built by the Danes in the 13th century, also known as the Dome Chrurch or St. Mary’s Cathedral, is Estonia’s oldest church. Originally a Roman Catholic cathedral, it became Lutheran in the mid 16th century and is the seat of Tallinn’s Archbishop of the Estonian Evangelical Lutheran Church. Although the church endured severe damage in the great fire of 1684, it was the only building on Toompea left standing. It was restored to its previous state shortly after the fire and a new baroque spire was added in the 18th century.

From the Church Square, we can see the light green colored Estonian Knighthood House. This is the 4th Knighthood house that was built for noble Knights to meet and enjoy festivities. The Knighthood was formed in 1584 by the Baltic German nobles, but it was disbanded in 1920. Currently, the building is used by the Estonian Academy of Arts. On the right of the building we take the Kohtu street until we reach the end and turn right onto a small open area between two buildings.

Kohtuotsa views: Towards the harbour and of the old town with skyscrapers in the distance.

A Panoramic View and Sweet Almonds

As we enter the Kohtuotsa viewing platform, which is a courtyard between two buildings, the smell of candied almonds overwhelms the senses. A wooden kiosk with a couple of girls dressed in traditional costume are making batches of sweet almonds in a copper pot. They have a sample for you to try, and when you do, the sale is complete. They have two options, Magus Mandel (Candied) or Soolane Mandel (Salty). I have the candied ones every time.

There is a stone wall at the end of the platform with amazing panoramic views of Tallinn. Looking to the left, you can see the white tower of St. Olaf’s Church amongst medieval towers with the harbour and the sea in the distance. Directly ahead are the roof tops and spires of the lower town with the skycrapers of the city in the distance. It’s quite a contrast of architecture from medieval structures to modern steel and glass.

Another nearby viewing platform is the Patkuli, which is reached by climbing 157 steps from the old town up to Toompea. This platform offers a great view of the harbour area.

Leaving the Kohtuotsa, we go back towards the Nevsky Cathedral and take the Long Leg Street down into the lower town. We walk along the fortification walls until we reach the Long Leg Tower and enter the lower town.

Walking down the Long Leg passage to the Long Leg Tower and into the lower town.

Vanalinn – Tallinn’s Lower Town

Emerging from the Long Leg Tower, we continue on Pikk street until we reach the Grand Guild Square (Suurgildi Plats). The square is named after the medieval gold colored Great Guild Hall that is now the Estonian History Museum. The Great Guild was a medieval association of merchants, artisans, and craftsmen in Tallinn from the 14th century until 1920. On the square, we also find the Lutheran Holy Spirit Church (Pühavaimu kirik). The white washed medieval church has stained glass gothic windows, an octagonal bell tower and an interesting 17th century carved clock on the façade. If you enter the church, you will see elaborate wood working, especially on the alter.

The Maiasmokk Café, the Holy Spirit Church, the church clock and the pharmacy sign.

Established in 1864, the Maiasmokk Café on the square, is the oldest in Tallinn. The café interior hasn’t changed for over a century. It is famous for its marzipan, which is said to have been originated in Tallinn. Marzipan is made from almond meal and either sugar or honey. The café’s Marzipan Room details the city’s history of making marzipan including traditional marzipan figures made from special molds.

If we take a small passage along the church, we will reach the Town Hall Square (Raekoja Plats). As we enter the square, two doors down on our left is the Town Hall Pharmacy (Revali Raeapteek). This pharmacy dates back to 1422, and it may be the world’s oldest pharmacy in continuous use.The pharmacy has a museum where you can see some of the old time medicines and potions. You can test various herbal tea blends picked from local fields in the basement of the Town Hall Pharmacy (or Raeapteek) or explore the exposition of the 17th to the 20th-century medicine in the back room. You can purchase some of the products from the middle ages including teas, spices, chocolate, marzipan and claret, a potent libation made from wine and spices that dates back to 1467.

The Old Town Square’s colorful buildings, the Town Hall and a Town Hall dragon water spout.

The lively Town Hall Square, one of the best preserved medieval town squares in the world, was a market place in the Middle ages. Many of the colorful buildings on the square were once medieval merchants’ homes, offices and warehouses from the Hanseatic Golden Age. During the summer months, the restaurants around the square set up their umbrellaed patios where you can enjoy lunch and a cool beverage as you watch locals and tourists mill about. Restaurants like “III Draakon” and ‘Olde Hansa” offer a unique medieval experience with menu items made with elk, bear and boar meat.

The square is the centre of the Old Town Days medieval festival, concerts, fairs and the centuries old Christmas market. It is said that in 1441, the Brotherhood of the Blackbeards, a professional association of merchants, ship owners and foreigners, erected the very first Christmas tree here on the square. Today, in addition to the tree, the Christmas market fills the square with kiosks selling everything from gingerbread to knitted mittens and handicrafts. Other kiosks sell snacks, oysters and mulled wine to keep you warm. Kids can drop off letters at the Santa Claus cabin and ride the carousels in a magical setting. On a stage, hundreds of performers take turns entertaining the crowds during the markets month long stay from the 27th of November to the 27th of December.

Sweet Almond vendor and Old Town buildings. The Christmas market stage and a kiosk.

The town hall, built in 1404, sits prominently on the square and is the oldest in the Baltic and Scandinavian regions. It is no longer in the seat of the municipal government but is used for special events and ceremonies, and is the home of the Tallinn City Musuem. The town hall tower can be climbed in the summer months to get another great view of Tallinn. Since 1530, a weather vane of Vana Toomas, or Old Thomas, has been keeping lookout atop the spire. Old Thomas, who is holding a sword and an arrow, is said to be a protector of Tallinn.

The square is spectacular, but it can be touristy. I like to wander through the cobblestone streets and alleyways surrounding the centre to find restaurants and cafes where the locals frequent. Walking these side streets is like taking a time machine back to the medieval ages, but you will find interesting little museums, galleries and shops selling local products like amber.

St. Catherine’s Passage kiosks and alley. The Viru Gate tower and the white Viru Hotel.

St. Catherine’s Passage, the Viru Gate and the KGB

From the Old Town square if we go to the right of the old town and down the busy pedestrian Viru Street we will reach the St. Catherine’s passage on Müürivahe Street. The passage leads to the St. Catherine’s Monastery which was founded in 1246 by the Monks of the Dominican Order. The monastery is the oldest building in Tallinn. At the monastery, you can visit the chapel, gallery, or book a private tour. The medieval passage itself, formerly known as Monk’s alley, has the tall fortification wall on one side with little kiosks below selling handicrafts and 15th to 17th century residences on the other side, with some now being used as artists workshops.

Only steps away from the St. Catherine’s passage is the 14th century Viru Gate that was part of Tallinn’s wall defences. When the entrances to the Old Town were widened in the late 1800’s, many of the gates were destroyed. The Viru Gate’s corner towers survived and are a great divide from the medieval town on one side and the modern city on the other.

During the 50 year Soviet occupation of Estonia, the KGB had its headquarters in the old town at Pagari 1. In its basement, suspected enemies of the state were imprisoned, interrogated and tortured. If convicted of crimes, they were either shot or sent to labour camps in Siberia. The tall white Viru Hotel that can be seen clearly in the distance from the Viru Gate has a KGB Museum. Like any hotel where foreigners stayed, the hotel had to have spying facilities for the KGB. The museum tells the story of their activities and the Soviet mindset.

St. Olaf’s Church, the Fat Margaret Tower, and the Kadriorg Palace.

St. Olaf’s Church

On the northern edge of the old town is Tallinn’s biggest medieval building, the iconic St Olaf’s Church. Named after the sainted Norwegian king Olav II Haraldsson, the church was the tallest building in the world from between 1549 and 1625 due to its 124 meter tower. The church had three great fires in 1625, 1820 and in 1931 caused by lightning striking its tall spire. In fact, lightning has struck the church at least 10 times. During the Soviet occupation, the spire was used as a radio tower and KGB surveillance point. Today, if you climb 232 steps on a winding staircase you will have a great view of the city and the harbour area. I’m not sure I would go on an overcast day tough.

Near the church is the Fat Margaret tower which houses a part of the Maritime Museum. The main part of the museum is the Seaplane Harbour (Lennusadam) which is located a couple of kilometers away. It is one of Europe’s biggest maritime museums with a submarine, icebreaker, seaplane, an aquarium, simulators and other activities.

Other Things to do in Tallinn

If you go to the wall connecting the Nunna, Sauna and Kuldjala towers, you can walk the city walls, like the medieval guards that protected the town.

Near the old town, the Rotermann quarter has been transformed from old warehouses and factory buildings into a trendy and lively neighborhood with modern architecture.

Kumu Art Museum, with a modern architectural design, depicts various periods of Estonian art from the Academic Style to Modernism, from Soviet Pop Art to contemporary art.

Near the Alexander Nevsky Cathedral, Tallinn’s Museum of Occupations tells the history of the country’s occupation by the Nazis during WWII and then the Soviets.

Patarei Prison is a huge complex in the Kalamaja district that can be visited in the summer months. Once an artillery battery in the 19th century, it became a prison from 1919 to 2002.

The 314 meter high Tallinn TV Tower has a glass-floored viewing platform on the 21st floor with a 360 degree view of the city. Thrill seekers can take a safety harnessed walk on the open deck.

Foodies may want to visit the Kalev Chocolate factory or the Baltic Station Market.

Just Outside of Tallinn

Just outside Tallinn is Kadriorg Park. Established by Peter the Great in 1718, it has the Kadriorg Palace as well as beautiful gardens and woods. The park includes a concert area, children’s park, a people’s park and a Japanese garden.

The 72 hectare Estonian Open-Air Museum has around 80 reconstructed buildings from the 18th to 20th centuries. The traditional structures were brought here from throughout Estonia.

Tallinn is not overly priced, or especially crowded with tourists. You can easily spend a few days in Tallinn, and it is well worth adding to any itinerary of Sweden or Finland. You will thank me for it.

Explore Europe With Us

Azorcan Global Sport, School and Sightseeing Tours have taken thousands to Europe on their custom group tours since 1994. Visit azorcan.net to see all our custom tour possibilities for your group of 26 or more. Individuals can join our “open” signature sport, sightseeing and sport fan tours including our popular Canada hockey fan tours to the World Juniors. At azorcan.net/media you can read our newsletters and listen to our podcasts.

Images compliments of Paul Almeida and Azorcan Tours.

Click here to read more stories from the series My European Favourites.

Business

Conservatives demand probe into Liberal vaccine injury program’s $50m mismanagement

From LifeSiteNews

The Liberals’ Vaccine Injury Support Program is accused of mismanaging a $50-million contract with Oxaro Inc. and failing to resolve claims for thousands of vaccine-injured Canadians.

Conservatives are calling for an official investigation into the Liberal-run vaccine injury program, which has cost Canadians millions but has little to show for it.

On July 14th, four Conservative Members of Parliament (MPs) signed a letter demanding answers after an explosive Global News report found the Liberals’ Vaccine Injury Support Program (VISP) misallocated taxpayer funds and disregarded many vaccine-injured Canadians.

“The federal government awarded a $50 million taxpayer-funded contract to Oxaro Inc. (formerly Raymond Chabot Grant Thornton Consulting Inc.). The purpose of this contract was to administer the VISP,” the letter wrote.

“However, there was no clear indication that Oxaro had credible experience in healthcare or in the administration of health-related claims raising valid questions about how and why this firm was selected,” it continued.

Canada’s VISP was launched in December 2020 after the Canadian government gave vaccine makers a shield from liability regarding COVID-19 jab-related injuries.

However, mismanagement within the program has led to many injured Canadians still waiting to receive compensation, while government contractors grow richer.

“Despite the $50 million contract, over 1,700 of the 3,100 claims remain unresolved,” the Conservatives continued. “Families dealing with life-altering injuries have been left waiting years for answers and support they were promised.”

Furthermore, the claims do not represent the total number of Canadians injured by the allegedly “safe and effective” COVID shots, as inside memos have revealed that the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) officials neglected to report all adverse effects from COVID shots and even went as far as telling staff not to report all events.

The PHAC’s downplaying of vaccine injuries is of little surprise to Canadians, as a 2023 secret memo revealed that the federal government purposefully hid adverse effect so as not to alarm Canadians.

Of the $50.6 million that Oxaro Inc., has received, $33.7 million has been spent on administrative costs, compared to only $16.9 million going to vaccine-injured Canadians.

The letter further revealed that former VISP employees have revealed that the program lacked professionalism, describing what Conservatives described as “a fraternity house rather than a professional organization responsible for administering health-related claims.”

“Reports of constant workplace drinking, ping pong, and Netflix are a slap in the face to taxpayers and the thousands of Canadians waiting for support for life altering injuries,” the letter continued.

Regardless of this, the Liberal government, under Prime Minister Mark Carney, is considering renewing its contract with Oxaro Inc.

Indeed, this would hardly be the first time that Liberals throw taxpayer dollars at a COVID program that is later exposed as ineffective and mismanaged.

Canada’s infamous ArriveCan app, which was mandated for all travelers in and out of Canada in 2020, has cost Canadians $54 million, despite the Public Health Agency of Canada admitting that they have no evidence that the program saved lives.

Details regarding the app and the government contracts surrounding it have been hidden from Canadians, as Liberals were exposed in 2023 for hiding a RCMP investigation into the app from auditors.

An investigation of the ArriveCan app began in 2022 after the House of Commons voted 173-149 for a full audit of the controversial app.

Business

Canada must address its birth tourism problem

By Sergio R. Karas for Inside Policy

One of the most effective solutions would be to amend the Citizenship Act, making automatic citizenship conditional upon at least one parent being a Canadian citizen or permanent resident.

Amid rising concerns about the prevalence of birth tourism, many Western democracies are taking steps to curb the practice. Canada should take note and reconsider its own policies in this area.

Birth tourism occurs when pregnant women travel to a country that grants automatic citizenship to all individuals born on its soil. There is increasing concern that birthright citizenship is being abused by actors linked to authoritarian regimes, who use the child’s citizenship as an anchor or escape route if the conditions in their country deteriorate.

Canada grants automatic citizenship by birth, subject to very few exceptions, such as when a child is born to foreign diplomats, consular officials, or international representatives. The principle known as jus soli in Latin for “right of the soil” is enshrined in Section 3(1)(a) of the Citizenship Act.

Unlike many other developed countries, Canada’s legislation does not consider the immigration or residency status of the parents for the child to be a citizen. Individuals who are in Canada illegally or have had refugee claims rejected may be taking advantage of birthright citizenship to delay their deportation. For example, consider the Supreme Court of Canada’s ruling in Baker v. Canada. The court held that the deportation decision for a Jamaican woman – who did not have legal status in Canada but had Canadian-born children – must consider the best interests of the Canadian-born children.

There is mounting evidence of organized birth tourism among individuals from the People’s Republic of China, particularly in British Columbia. According to a January 29 news report in Business in Vancouver, an estimated 22–23 per cent of births at Richmond Hospital in 2019–20 were to non-resident mothers, and the majority were Chinese nationals. The expectant mothers often utilize “baby houses” and maternity packages, which provide private residences and a comprehensive bundle of services to facilitate the mother’s experience, so that their Canadian-born child can benefit from free education and social and health services, and even sponsor their parents for immigration to Canada in the future. The financial and logistical infrastructure supporting this practice has grown, with reports of dozens of birth houses in British Columbia catering to a Chinese clientele.

Unconditional birthright citizenship has attracted expectant mothers from countries including Nigeria and India. Many arrive on tourist visas to give birth in Canada. The number of babies born in Canada to non-resident mothers – a metric often used to measure birth tourism – dropped sharply during the COVID-19 pandemic but has quickly rebounded since. A December 2023 report in Policy Options found that non-resident births constituted about 1.6 per cent of all 2019 births in Canada. That number fell to 0.7 per cent in 2020–2021 due to travel restrictions, but by 2022 it rebounded to one per cent of total births. That year, there were 3,575 births to non-residents – 53 per cent more than during the pandemic. Experts believe that about half of these were from women who travelled to Canada specifically for the purpose of giving birth. According to the report, about 50 per cent of non-resident births are estimated to be the result of birth tourism. The upward trend continued into 2023–24, with 5,219 non-resident births across Canada.

Some hospitals have seen more of these cases than others. For example, B.C.’s Richmond Hospital had 24 per cent of its births from non-residents in 2019–20, but that dropped to just 4 per cent by 2022. In contrast, Toronto’s Humber River Hospital and Montreal’s St. Mary’s Hospital had the highest rates in 2022–23, with 10.5 per cent and 9.4 per cent of births from non-residents, respectively.

Several developed countries have moved away from unconditional birthright citizenship in recent years, implementing more restrictive measures to prevent exploitation of their immigration systems. In the United Kingdom, the British Nationality Act abolished jus soli in its unconditional form. Now, a child born in the UK is granted citizenship only if at least one parent is a British citizen or has settled status. This change was introduced to prevent misuse of the immigration and nationality framework. Similarly, Germany follows a conditional form of jus soli. According to its Nationality Act, a child born in Germany acquires citizenship only if at least one parent has legally resided in the country for a minimum of eight years and holds a permanent residence permit. Australia also eliminated automatic birthright citizenship. Under the Australian Citizenship Act, a child born on Australian soil is granted citizenship only if at least one parent is an Australian citizen or permanent resident. Alternatively, if the child lives in Australia continuously for ten years, they may become eligible for citizenship through residency. These policies illustrate a global trend toward limiting automatic citizenship by birth to discourage birth tourism.

In the United States, Section 1 of the Citizenship Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution prescribes that “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.” The Trump administration has launched a policy and legal challenge to the longstanding interpretation that every person born in the US is automatically a citizen. It argues that the current interpretation incentivizes illegal immigration and results in widespread abuse of the system.

On January 20, 2025, President Donald Trump issued Executive Order 14156: Protecting the Meaning and Value of American Citizenship, aimed at ending birthright citizenship for children of undocumented migrants and those with lawful but temporary status in the United States. The executive order stated that the Fourteenth Amendment’s Citizenship Clause “rightly repudiated” the Supreme Court’s “shameful decision” in the Dred Scott v. Sandford case, which dealt with the denial of citizenship to black former slaves. The administration argues that the Fourteenth Amendment “has never been interpreted to extend citizenship universally to anyone born within the United States.” The executive order claims that the Fourteenth Amendment has “always excluded from birthright citizenship persons who were born in the United States but not subject to the jurisdiction thereof.” The order outlines two categories of individuals that it claims are not subject to United States jurisdiction and thus not automatically entitled to citizenship: a child of an undocumented mother and father who are not citizens or lawful permanent residents; and a child of a mother who is a temporary visitor and of a father who is not a citizen or lawful permanent resident. The executive order attempts to make ancestry a criterion for automatic citizenship. It requires children born on US soil to have at least one parent who has US citizenship or lawful permanent residency.

On June 27, 2025, the US Supreme Court in Trump v. CASA, Inc. held that lower federal courts exceed their constitutional authority when issuing broad, nationwide injunctions to prevent the Trump administration from enforcing the executive order. Such relief should be limited to the specific plaintiffs involved in the case. The Court did not address whether the order is constitutional, and that will be decided in the future. However, this decision removes a major legal obstacle, allowing the administration to enforce the policy in areas not covered by narrower injunctions. Since the order could affect over 150,000 newborns each year, future decisions on the merits of the order are still an especially important legal and social issue.

In addition to the executive order, the Ban Birth Tourism Act – introduced in the United States Congress in May 2025 – aims to prevent women from entering the country on visitor visas solely to give birth, citing an annual 33,000 births to tourist mothers. Simultaneously, the State Department instructed US consulates abroad to deny visas to applicants suspected of “birth tourism,” reinforcing a sharp policy pivot.

In light of these developments, Canada should be wary. It may see an increase in birth tourism as expectant mothers look for alternative destinations where their children can acquire citizenship by birth.

Canadian immigration law does not prevent women from entering the country on a visitor visa to give birth. The Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (IRPA) and the associated regulations do not include any provisions that allow immigration officials or Canada Border Services officers to deny visas or entry based on pregnancy. Section 22 of the IRPA, which deals with temporary residents, could be amended. However, making changes to regulations or policy would be difficult and could lead to inconsistent decisions and a flurry of litigation. For example, adding questions about pregnancy to visa application forms or allowing officers to request pregnancy tests in certain high-risk cases could result in legal challenges on the grounds of privacy and discrimination.

In a 2019 Angus Reid Institute survey, 64 per cent of Canadians said they would support changing the law to stop granting citizenship to babies born in Canada to parents who are only on tourist visas. One of the most effective solutions would be to amend Section 3(1)(a) of the Citizenship Act, making it mandatory that at least one parent be a Canadian citizen or permanent resident for a child born in Canada to automatically receive citizenship. Such a model would align with citizenship legislation in countries like the UK, Germany, and Australia, where jus soli is conditional on parental status. Making this change would close the current loophole that allows birth tourism, without placing additional pressure on visa officers or requiring new restrictions on tourist visas. It would retain Canada’s inclusive citizenship framework while aligning with practices in other democratic nations.

Canada currently lacks a proper and consistent system for collecting data on non-resident births. This gap poses challenges in understanding the scale and impact of birth tourism. Since health care is under provincial jurisdiction, the responsibility for tracking and managing such data falls primarily on the provinces. However, there is no national framework or requirement for provinces or hospitals to report the number of births by non-residents, leading to fragmented and incomplete information across the country. One notable example is BC’s Richmond Hospital, which has become a well-known birth tourism destination. In the 2017–18 fiscal year alone, 22 per cent of all births at Richmond Hospital were to non-resident mothers. These births generated approximately $6.2 million in maternity fees, out of which $1.1 million remained unpaid. This example highlights not only the prevalence of the practice but also the financial burden it places on the provincial health care programs. To better address the issue, provinces should implement more robust data collection practices. Information should include the mother’s residency or visa status, the total cost of care provided, payment outcomes (including outstanding balances), and any necessary medical follow-ups.

Reliable and transparent data is essential for policymakers to accurately assess the scope of birth tourism and develop effective responses. Provinces should strengthen data collection practices and consider introducing policies that require security deposits or proof of adequate medical insurance coverage for expectant mothers who are not covered by provincial healthcare plans.

Canada does not currently record the immigration or residency status of parents on birth certificates, making it difficult to determine how many children are born to non-resident or temporary resident parents. Including this information at the time of birth registration would significantly improve data accuracy and support more informed policy decisions. By improving data collection, increasing transparency, and adopting preventive financial safeguards, provinces can more effectively manage the challenges posed by birth tourism, and the federal government can implement legislative reforms to deal with the problem.

Sergio R. Karas, principal of Karas Immigration Law Professional Corporation, is a certified specialist in Canadian citizenship and immigration law by the Law Society of Ontario. He is co-chair of the ABA International Law Section Immigration and Naturalization Committee, past chair of the Ontario Bar Association Citizenship and Immigration Section, past chair of the International Bar Association Immigration and Nationality Committee, and a fellow of the American Bar Foundation. He can be reached at [email protected]. The author is grateful for the contribution to this article by Jhanvi Katariya, student-at-law.

-

Alberta8 hours ago

Alberta8 hours agoMedian workers in Alberta could receive 72% more under Alberta Pension Plan compared to Canada Pension Plan

-

Opinion1 day ago

Opinion1 day agoPreston Manning: Three Wise Men from the East, Again

-

COVID-191 day ago

COVID-191 day agoTrump DOJ dismisses charges against doctor who issued fake COVID passports

-

Uncategorized2 days ago

Uncategorized2 days agoCNN’s Shock Climate Polling Data Reinforces Trump’s Energy Agenda

-

Addictions1 day ago

Addictions1 day agoWhy B.C.’s new witnessed dosing guidelines are built to fail

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoMark Carney’s Fiscal Fantasy Will Bankrupt Canada

-

Energy23 hours ago

Energy23 hours agoActivists using the courts in attempt to hijack energy policy

-

Alberta16 hours ago

Alberta16 hours agoAlberta ban on men in women’s sports doesn’t apply to athletes from other provinces