Crime

Edmonton Police release suspect images connected to Tuesday homicide

The Edmonton Police Service is releasing images of a male suspect alleged to be responsible for the death of a 42-year-old male in northeast Edmonton early Tuesday morning.

Homicide Section investigators are seeking the public’s assistance in locating Matthew Leonard Dawson Campeau, 24.

Campeau is wanted in connection to the murder of a 42-year-old male, which occurred at approximately 12:40 a.m. Tuesday, Feb. 26, 2019, at a residence near Belmont Park in northeast Edmonton.

Autopsy results released by the Edmonton Medical Examiner this morning confirm the 42-year-old male died from a gun-shot wound, and the manner of death is homicide.

Homicide investigators believe Campeau may still be in the Edmonton area. He is considered to be armed and dangerous and should not be approached.

Campeau is described as being a Caucasian male, 6’2”, brown eyes, short black hair and weighs approximately 186 pounds. He also has a tattoo of an arrow on his left hand.

Matthew Leonard Dawson Campeau, 24

Investigators are urging anyone with information regarding the whereabouts of Campeau to contact the EPS at 780-423-4567 or #377 from a mobile phone. Anonymous information can also be submitted to Crime Stoppers at 1-800-222-8477 or online at www.tipsubmit.com/start.htm.

Background:

Northeast Division patrol officers responded to a 911 call in connection to shots being fired at a residence near 135 Avenue and 38 Street, at approximately 12:40 a.m., Feb. 26, 2019.

Upon arrival, EPS officers found a deceased male inside the residence. The male is known to police.

Crime

The Uncomfortable Demographics of Islamist Bloodshed—and Why “Islamophobia” Deflection Increases the Threat

Addressing realities directly is the only path toward protecting communities, confronting extremism, and preventing further loss of life, Canadian national security expert argues.

After attacks by Islamic extremists, a familiar pattern follows. Debate erupts. Commentary and interviews flood the media. Op-eds, narratives, talking points, and competing interpretations proliferate in the immediate aftermath of bloodshed. The brief interval since the Bondi beach attack is no exception.

Many of these responses condemn the violence and call for solidarity between Muslims and non-Muslims, as well as for broader societal unity. Their core message is commendable, and I support it: extremist violence is horrific, societies must stand united, and communities most commonly targeted by Islamic extremists—Jews, Christians, non-Muslim minorities, and moderate Muslims—deserve to live in safety and be protected.

Yet many of these info-space engagements miss the mark or cater to a narrow audience of wonks. A recurring concern is that, at some point, many of these engagements suggest, infer, or outright insinuate that non-Muslims, or predominantly non-Muslim societies, are somehow expected or obligated to interpret these attacks through an Islamic or Muslim-impact lens. This framing is frequently reinforced by a familiar “not a true Muslim” narrative regarding the perpetrators, alongside warnings about the risks of Islamophobia.

These misaligned expectations collide with a number of uncomfortable but unavoidable truths. Extremist groups such as ISIS, Al-Qaeda, Hamas, Hezbollah, and decentralized attackers with no formal affiliations have repeatedly and explicitly justified their violence through interpretations of Islamic texts and Islamic history. While most Muslims reject these interpretations, it remains equally true that large, dynamic groups of Muslims worldwide do not—and that these groups are well prepared to, and regularly do, use violence to advance their version of Islam.

Islamic extremist movements do not, and did not, emerge in a vacuum. They draw from the broader Islamic context. This fact is observable, persistent, and cannot be wished or washed away, no matter how hard some may try or many may wish otherwise.

Given this reality, it follows that for most non-Muslims—many of whom do not have detailed knowledge of Islam, its internal theological debates, historical divisions, or political evolution—and for a considerable number of Muslims as well, Islamic extremist violence is perceived as connected to Islam as it manifests globally. This perception persists regardless of nuance, disclaimers, or internal distinctions within the faith and among its followers.

THE COST OF DENIAL AND DEFLECTION

Denying or deflecting from these observable connections prevents society from addressing the central issues following an Islamic extremist attack in a Western country: the fatalities and injuries, how the violence is perceived and experienced by surviving victims, how it is experienced and understood by the majority non-Muslim population, how it is interpreted by non-Muslim governments responsible for public safety, and how it is received by allied nations. Worse, refusing to confront these difficult truths—or branding legitimate concerns as Islamophobia—creates a vacuum, one readily filled by extremist voices and adversarial actors eager to poison and pollute the discussion.

Following such attacks, in addition to thinking first of the direct victims, I sympathize with my Muslim family, friends, colleagues, moderate Muslims worldwide, and Muslim victims of Islamic extremism, particularly given that anti-Muslim bigotry is a real problem they face. For Muslim victims of Islamic extremism, that bigotry constitutes a second blow they must endure. Personal sympathy, however, does not translate into an obligation to center Muslim communal concerns when they were not the targets of the attack. Nor does it impose a public obligation or override how societies can, do, or should process and respond to violence directed at them by Islamic extremists.

As it applies to the general public in Western nations, the principle is simple: there should be no expectation that non-Muslims consider Islam, inter-Islamic identity conflicts, internal theological disputes, or the broader impact on the global Muslim community, when responding to attacks carried out by Islamic extremists. That is, unless Muslims were the victims, in which case some consideration is appropriate.

Quite bluntly, non-Muslims are not required to do so and are entitled to reject and push back against any suggestion that they must or should. Pointedly, they are not Muslims, a fact far too many now seem to overlook.

The arguments presented here will be uncomfortable for many and will likely provoke polarizing discussion. Nonetheless, they articulate an important, human-centered position regarding how Islamic extremist attacks in Western nations are commonly interpreted and understood by non-Muslim majority populations.

Non-Muslims are free to give no consideration to Muslim interests at any time, particularly following an Islamic extremist attack against non-Muslims in a non-Muslim country. The sole exception is that governments retain an obligation to ensure the safety and protection of their Muslim citizens, who face real and heightened threats during these periods. This does not suggest that non-Muslims cannot consider Muslim community members; it simply affirms that they are under no obligation to do so.

The impulse for Muslims to distance moderate Muslims and Islam from extremist attacks—such as the targeting of Jews in Australia or foiled Christmas market plots in Poland and Germany—is understandable.

Muslims do so to protect their own interests, the interests of fellow Muslims, and the reputation of Islam itself. Yet this impulse frequently collapses into the “No True Scotsman” fallacy, pointing to peaceful Muslims as the baseline while asserting that the attackers were not “true Muslims.”

Such claims oversimplify the reality of Islam as it manifests globally and fail to address the legitimate political and social consequences that follow Islamic extremist attacks in predominantly non-Muslim Western societies. These deflections frequently produce unintended effects, such as strengthening anti-Muslim extremist sentiments and movements and undermining efforts to diminish them.

The central issue for public discourse after an Islamic extremist attack is not debating whether the perpetrators were “true” or “false” Muslims, nor assessing downstream impacts on Muslim communities—unless they were the targets.

It is a societal effort to understand why radical ideologies continue to emerge from varying—yet often overlapping—interpretations of Islam, how political struggles within the Muslim world contribute to these ideologies, and how non-Muslim-majority Western countries can realistically and effectively confront and mitigate threats related to Islamic extremism before the next attack occurs and more non-Muslim and Muslim lives are lost.

Addressing these realities directly is the only path toward protecting communities, confronting extremism, and preventing further loss of life.

Ian Bradbury, a global security specialist with over 25 years experience, transitioned from Defence and NatSec roles to found Terra Nova Strategic Management (2009) and 1NAEF (2014). A TEDx, UN, NATO, and Parliament speaker, he focuses on terrorism, hybrid warfare, conflict aid, stability operations, and geo-strategy.

The Bureau is a reader-supported publication.

To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Crime

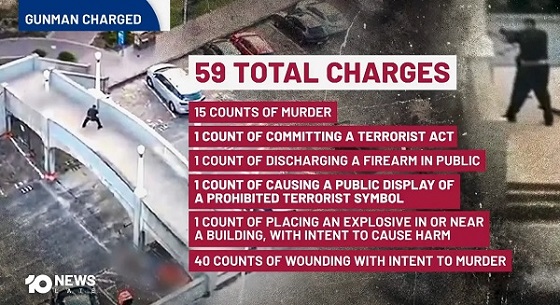

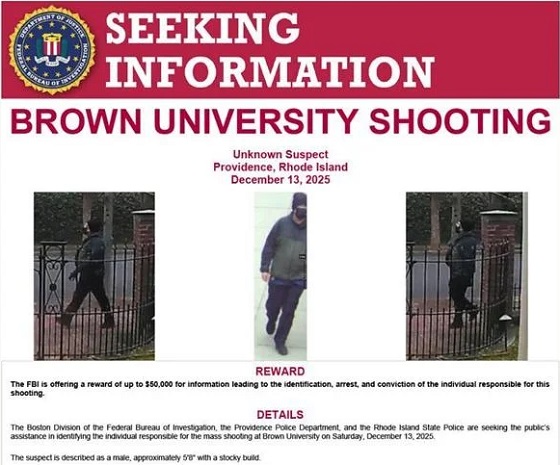

Brown University shooter dead of apparent self-inflicted gunshot wound

From The Center Square

By

Rhode Island officials said the suspected gunman in the Brown University mass shooting has been found dead of an apparent self-inflicted gunshot wound, more than 50 miles away in a storage facility in southern New Hampshire.

The shooter was identified as Claudio Manuel Neves-Valente, a 48-year-old Brown student and Portuguese national. Neves-Valente was found dead with a satchel containing two firearms inside in the storage facility, authorities said.

“He took his own life tonight,” Providence police chief Oscar Perez said at a press conference, noting that local, state and federal law officials spent days poring over video evidence, license plate data and hundreds of investigative tips in pursuit of the suspect.

Perez credited cooperation between federal state and local law enforcement officials, as well as the Providence community, which he said provided the video evidence needed to help authorities crack the case.

“The community stepped up,” he said. “It was all about groundwork, public assistance, interviews with individuals, and good old fashioned policing.”

Rhode Island Attorney General Peter Neronha said the “person of interest” identified by private videos contacted authorities on Wednesday and provided information that led to his whereabouts.

“He blew the case right open, blew it open,” Neronha said. “That person led us to the car, which led us to the name, which led us to the photograph of that individual.”

“And that’s how these cases sometimes go,” he said. “You can feel like you’re not making a lot of progress. You can feel like you’re chasing leaves and they don’t work out. But the team keeps going.”

The discovery of the suspect’s body caps an intense six-day manhunt spanning several New England states, which put communities from Providence to southern New Hampshire on edge.

“We got him,” FBI special agent in charge for Boston Ted Docks said at Thursday night’s briefing. “Even though the suspect was found dead tonight our work is not done. There are many questions that need to be answered.”

He said the FBI deployed around 500 agents to assist local authorities in the investigation, in addition to offering a $50,000 reward. He says that officials are still looking into the suspect’s motive.

Two students were killed and nine others were injured in the Brown University shooting Saturday, which happened when an undetected gunman entered the Barus and Holley building on campus, where students were taking exams before the holiday break. Providence authorities briefly detained a person in the shooting earlier in the week, but then released them.

Investigators said they are also examining the possibility that the Brown case is connected to the killing of a Massachusetts Institute of Technology professor in his hometown.

An unidentified gunman shot MIT professor Nuno Loureiro multiple times inside his home in Brookline, about 50 miles north of Providence, according to authorities. He died at a local hospital on Tuesday.

Leah Foley, U.S. attorney for Massachusetts, was expected to hold a news briefing late Thursday night to discuss the connection with the MIT shooting.

-

International2 days ago

International2 days agoOttawa is still dodging the China interference threat

-

Agriculture6 hours ago

Agriculture6 hours agoEnd Supply Management—For the Sake of Canadian Consumers

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoThere’s No Bias at CBC News, You Say? Well, OK…

-

Automotive2 days ago

Automotive2 days agoCanada’s EV gamble is starting to backfire

-

Digital ID4 hours ago

Digital ID4 hours agoCanadian government launches trial version of digital ID for certain licenses, permits

-

Alberta3 hours ago

Alberta3 hours agoAlberta Next Panel calls to reform how Canada works

-

Business60 mins ago

Business60 mins agoThe “Disruptor-in-Chief” places Canada in the crosshairs

-

International2 days ago

International2 days ago2025: The Year The Narrative Changed