Brownstone Institute

Did Lockdowns Signify the “End of Abundance?”

From the Brownstone Institute

BY

French President Emmanuel Macron gave a speech not long ago in which he made a rather shocking prediction about the future of his nation and presumably the rest of the world.

“What we are currently living through is a kind of major tipping point or a great upheaval … we are living the end of what could have seemed an era of abundance … the end of the abundance of products of technologies that seemed always available … the end of the abundance of land and materials including water….”

The G7 leader’s words of warning about the literal end of material prosperity caught my eye in a way that most headlines do not. I also noticed that Paris switched off the lights on the Eiffel Tower to save a meager amount of electricity, providing a potent symbol to underscore Macron’s message about the “End of Abundance.”

In this era of economic chaos, disrupted supply chains, ruinous inflation, a severe energy crunch in Europe, tensions between nuclear superpowers, and extreme political polarization, plus intense worries (in some quarters, at least) about climate change, there are emerging signs of a belief in the once unthinkable: the possibility that Progress with a capital “P” may no longer be assured.

It should be obvious at this point that Covid-19 lockdowns and related pandemic policies, including the printing of trillions of dollars to paper over the intentional disruption of society, played a major role in bringing about today’s negative economic conditions. These conditions could last a very long time, particularly considering the mild political blowback to Covid chaos that we saw during the midterm elections. Brownstone’s Jeffrey Tucker has written about the potentially far-reaching effects of lockdowns:

“But what if we aren’t really observing a cycle? What if we are living through a long shock in which our economic lives have been fundamentally upended? What if it will be many years before anything that we knew as prosperity returns if it ever does? … In other words, it is very possible that the lockdowns of March 2020 were the starting point of the greatest economic depression in our lifetimes or perhaps in hundreds of years.”

The worst depression in hundreds of years? That would be since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, more or less. The Bank of England, incidentally, just warned that the UK is facing the longest recession since records began. The historical forces we are living through now might be so big that most of us might not even recognize them until much later.

Taking the long view, we should ask ourselves: were lockdowns the initial cause of the chaos we are experiencing, or were they the unfortunate result of a larger historical phenomenon that we are just now beginning to understand? As Tucker noted, “[i]n the 1930s, no one knew that they were living through what came to be called the Great Depression.” So it is fair to ask, would you know if lockdowns were the first crisis of an era that will one day come to be called the “End of Abundance?”

Thinking the Unthinkable

The “End of Abundance” is a radical concept, but then again so is shutting down the whole world.

The utterly radical nature of the ideas that gave rise to Covid-19 lockdowns are striking. In August of 2020, Anthony Fauci wrote that the goal of his policies was nothing less than to “rebuild the infrastructure of human existence.”

During that time we heard the constant refrain from Joe Biden, Boris Johnson, and other world leaders: “Build Back Better.” And from the Davos technocrats at the World Economic Forum (WEF) we have heard talk of the “Fourth Industrial Revolution,” which to them means “merging the physical, digital and biological world” in order to fundamentally change “what it means to be human.”

Locking down the population and subjecting it to draconian restrictions is, for some reason, absolutely central to their vision of changing “what it means to be human.” Bill Gates and other influential elites have pointed to the Covid-19 response as their template for addressing future challenges, and have even floated the possibility of future climate lockdowns (no, sadly this is not a conspiracy theory).

The million-dollar question that many have tried to answer is, “Why now?” Why, at this point in history, do elites insist on the power to lock down the world? Why, after decades of post-World War Two prosperity, have so many abandoned values that are fundamental to our civilization? Why, in the second decade of the 21st century, are we taking a nosedive off the elevator of “Progress?”

There is no shortage of theories as to “Why now?” There are many critics of the WEF’s “Fourth Industrial Revolution” and the “Great Reset,” for example, who say that elites have cooked up imaginary challenges like climate change and “saving the planet” as excuses for the exercise of tyrannical power, in what amounts to a big scam.

I am not satisfied with those kinds of answers, even though I think they contain elements of truth, given that elites obviously use certain issues as a pretext. To my mind, environmental concerns definitely are not a scam (although the “solutions” often are). What has been happening since March 2020 is much bigger than a scam. The radical ideas underlying the lockdown mentality simply must have a more radical motivation behind them. These people literally just tried to shut down the entire world and reboot it like a malfunctioning computer!

If you are looking for the most profound motivation possible for the incredibly radical lockdown mentality and the vast destruction it has wrought, I would submit that you could do no better than the “End of Abundance.” And what does “Abundance” mean exactly? I think it can be summarized in a single word: Growth. The “End of Abundance” means the End of Growth.

Imagining Limits to Growth

“We don’t know how to make a zero-growth society work,” conservative tech billionaire Peter Thiel said in an interview for Unherd, in which he claimed that Covid-19 lockdowns resulted from the long-term stagnation of growth and innovation in our society. His argument is that as society has slowly stagnated over the past several decades, we have tacitly abandoned the aspiration to growth, leading to a sort of malaise that has “resulted in something like a societal and cultural lockdown; not just the last two years but in many ways the last 40 or 50.”

Thiel contends that limits to growth are not inevitable, but that the belief in limits is a kind of self-fulfilling prophecy. He calls this “a long, slow victory of the Club of Rome,” the global think tank that published the famous book—some would call it infamous—The Limits to Growth fifty years ago.

His statement “We don’t know how to make a zero-growth society work” is spot on. Limits of any kind are anathema to growth-based, industrially developed countries in which everything is built on the premise of perpetual growth.

This is why, for most people, the end of economic growth is absolutely unimaginable. But not for everyone.

For me, the end of growth has been something of a preoccupation for about ten years, since I first read The Limits to Growth. My reaction to the book was similar to Thiel’s only in the sense that I agree that the end of growth would be a cataclysm for our growth-based society. Unlike him, I do not see the limits to growth as merely a self-fulfilling prophecy, but rather as an accurate description of the very real physical and biological limits of a finite planet.

The premise of The Limits to Growth, based on a major study conducted by researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), is that natural resources and the capacity of the planet to absorb industrial pollution are limited, and therefore infinite economic growth on a finite planet is impossible. The original study, which has been reviewed and updated over the years, projected various scenarios in which an end to growth of the global industrial economy—a long-term decline in industrial output, the availability of non-renewable natural resources, industrial pollution, food production, and population—would start at some point in the first one-third to one-half of the 21st century. Right about now.

The Limits to Growth was extremely controversial from the moment it was published. Prominent Western leaders attacked the notion of limits as a dangerous delusion. The Right refused to accept limits, believing that human ingenuity and technological innovation will always overcome whatever ecological limits exist.

After briefly preaching limits, the progressive Left abandoned that faith, too, and now believes that limits can be overcome with some combination of activist government and “green” technologies like solar panels and wind turbines (e.g. the “Green New Deal”). Even climate-change models that predict catastrophic levels of warming this century assume global GDP growth through the year 2100.

The vast majority of people in our society, both Right and Left, have never taken the idea of limits to growth seriously. But what if you are in that small group of people who have taken the concept seriously? And what if you have stuck to the basic belief that infinite growth on a finite planet is impossible? What might you have expected to see at this point in the 21st century?

Chaos, essentially. The breakdown of the social contract. Civil strife. A mental-health crisis. Declining life expectancy. The spread of irrational beliefs. The destructive urge to tear down rather than build up. Dangerous levels of inflation. A global food crisis. People eating crickets and drinking cockroach milk. The extinction of two-thirds of the Earth’s wildlife. The disruption of fragile supply chains. The rapid accumulation of debts.

The printing of vast amounts of money. A quarter of American adults so stressed they cannot function. Plastic pollution (like five billion Covid masks) filling the oceans. Wildfires and floods. Diesel fuel shortages. Unprecedented financial and economic dislocations. Scary new terms like “poly-crisis.” Desperate grasping for solutions. Warnings from the United Nations that we are at risk of “total societal collapse” due to climate change, ecosystem failure, and economic fragility, and urging the “rapid transformation of societies”. Add to that list a procession of global leaders making strange, grandiose declarations about the need to “rebuild human existence” and “change what it means to be human.”

In other words, if you were waiting for the limits to growth to start kicking in at this point in the second decade of the 21st century, you might have expected to see the kinds of disturbing things that we have been witnessing in recent years. Dennis Meadows, lead author of The Limits to Growth, has said that the projections of his fifty-year-old study “resemble what we are experiencing” in the world currently.

Meadows has not criticized Covid lockdowns, but he has confirmed that his study showed “growth was going to stop around 2020”—the year that the whole world just happened to shut down—and would be accompanied by all sorts of unpredictable and potentially extreme “psychological, social, and political factors.” It should be further noted that the head of the International Monetary Fund, Kristalina Georgieva, gave a speech on October 1, 2019, mere months before global lockdowns, in which she warned of a “synchronized slowdown” of the global economy covering “90 percent of the world,” creating “a serious risk that services and consumption could soon be affected.”

The coincidences in timing are remarkable. The predicted end of growth, an actual slowdown in global growth, and the lockdown of the entire globe all converged in 2020. Does this necessarily mean The Limits to Growth was right, or that lockdowns were a direct response to limited growth? No, but again the current state of the world is eerily consistent with the pandemonium that you might have expected had you taken the concept of limits to growth seriously.

Speaking for myself, when I first became aware of the implications of the limits to growth in 2014 and 2015, I told my close friends and family, “The 2020s will be chaotic.” Three months into the start of the new decade, when the whole world suddenly came to a grinding halt, I began to recall the prediction I had made. Three years into one of the most chaotic decades in history, I am beginning to worry that I was onto something.

Interestingly, whether you believe that biological and physical limits to growth truly exist, as I do, or you believe that limits to growth are merely a figment of some fevered Malthusian imagination that has somehow manifested itself in the real world, as Thiel seems to think, the result is arguably the same: the “End of Abundance.”

Limits and Lockdowns

Thiel is not the only one who has linked lockdowns to the limits to growth. While almost everyone on the environmental Left supported lockdowns or at least refrained from speaking out against them, there are a handful of heterodox environmental thinkers—those who tend to be skeptical of partisan narratives, corporate power, and technocratic “solutions”—who have connected the dots between limits and lockdowns.

The British novelist and essayist Paul Kingsnorth, for example, has written that “we have no idea what to do about the coming end of the brief age of abundance, and the reappearance, armed and dangerous, of what we could get away with denying for a few decades: limits.”

Kingsnorth, an Orthodox Christian and an unorthodox environmentalist (he calls himself a “recovering environmentalist”), has vigorously criticized the technocratic response to the pandemic, observing that Covid “was used as a trial run for precisely the kind of technologies…which are now increasingly sold to us as a means of ‘saving the planet.’” He says that the Brave New World that the technocrats are trying to build, with its machine-like desire to exert control over everyone and everything, is unable to recognize limits of any kind, whether natural or moral.

Professor Jem Bendell of the University of Cumbria is one of the few on the environmental Left who has spoken out against authoritarian Covid policies. He is known for his “Deep Adaptation” paper describing the severe disruptions to society that he believes will result from climate change. He has criticized lockdowns, mandates, and other non-democratic responses to the pandemic, suggesting they are a form of “Elite Panic”—a panicked reaction of a social elite to a disaster event, with a focus on measures of command and control—which parallels a potentially similar panic among elites regarding climate change that “could inspire leaders to curtail personal freedoms.”

Panic, the desire for control, and the curtailment of personal freedoms. Yes, I find that to be a very good summary of the story we have been living for two and a half years.

If we dig deeper into the assumptions and beliefs of Western elites, it becomes clear that they are afraid that the global economy, especially their own way of life, is threatened by “limiting” factors. This fear is a driving force behind their support for lockdowns and other radical ideas they have concocted in an attempt to overcome those limits and protect themselves. Panicking elites in Western society may not specifically believe in the “limits to growth,” or use those words, but they feel in their bones that systemic global risks are getting worse.

Lockdowns, it is crucial to recognize, are not a mere sideshow in the “End of Abundance” drama. They play a starring role. Remember, as Thiel said, we do not know how to make a no-growth or even a low-growth society work. Only through some radical new approach to governance can a stagnant or declining economy be managed.

When the economic pie is growing everyone can get a larger slice, but when the pie is shrinking everyone must share the pain, unless a small number of powerful people find a way to seize a bigger slice of a smaller pie at the expense of everyone else. That is what lockdowns were all about.

Lockdowns and “The Mindset” for Coping with the “End of Abundance”

In the novel, Gone with the Wind, the Southern aristocrat Rhett Butler described his philosophy of profiting from the disintegration of the Old South. “I told you once before that there were two times for making big money,” he said to Scarlett, “one in the up-building of a country and the other in its destruction. Slow money on the up-building, fast money in the crack-up.”

Western elites appear to have a similar attitude toward the “crack-up” of the Old Normal.

For years the elite Davos crowd has been active in making plans for the end of the world as we know it. They have extensive plans to profit from “green” energy and other ostensibly “sustainable” responses to environmental limits: insect protein, fake meat, gene-edited crops, factory foods, capture of carbon dioxide, etc. They also tend to own “doomsday” compounds and underground bunkers—Thiel has a luxury bolthole in New Zealand—and spend substantial time and resources planning for catastrophic end-of-civilization scenarios.

The Italian scientist Ugo Bardi, a member of the Club of Rome who co-edited the fifty-year update to The Limits to Growth, has compared bunker-owning elites to those of the collapsing Roman Empire. “We see a pattern,” he says. “When the rich Romans saw that things were going really out of control, they scrambled to save themselves while, at the same time, denying that things were so bad.” Many elites fled to their bunkers during the pandemic, as Covid-19 brought their long-simmering fears of social disruption to the forefront.

Technology writer Douglas Rushkoff’s recent book, Survival of the Richest, documents in detail the habits of mind of uber-elites who have been prepping for social collapse. His book is based on a talk he was invited to give to a group of five ultra-wealthy men, including two billionaires, in 2017. Rushkoff thought he had been invited to speak about the future of technology, so he was surprised when the men only wanted to ask questions about something they called “The Event.”

“The Event,” wrote Rushkoff. “That was their euphemism for the environmental collapse, social unrest, nuclear explosion, unstoppable virus, or Mr. Robot hack that takes everything down.” Read that again. Unstoppable virus. This was over two years before Covid-19.

The five powerful men’s interest revolved around a key question asked by one of them, the CEO of a brokerage house. He was desperate to know, “How do I maintain authority over my security force after The Event?”

“This single question occupied up for the rest of the hour . . . . [H]ow would he pay the guards once even his crypto was worthless? What would stop the guards from eventually choosing their own leader?

The billionaires considered using special combination locks on the food supply that only they knew. Or making guards wear disciplinary collars of some kind in return for their survival. Or maybe building robots to serve as guards and workers – if that technology could be developed “in time.”

I tried to reason with them. I made pro-social arguments for partnership and solidarity as the best approaches to our collective, long-term challenges . . . . They rolled their eyes at what must have sounded to them like hippy philosophy.

Rushkoff calls the outlook of these five men—a representative slice of the power elite in Silicon Valley, Wall Street, Washington, DC, and Davos—The Mindset. “The Mindset,” he writes, “allows for the easy externalization of harm to others, and inspires a corresponding longing for transcendence and separation from the people and places that have been abused.” Those with The Mindset, he says, believe that they can use their wealth, power, and technology to somehow “leave the rest of us behind.”

Does The Mindset sound familiar? It should, because it is a great description of how global elites (and their white-collar functionaries in the laptop class) responded to Covid-19. They pushed all the pain of locking down society onto average people, while seeking to avoid the catastrophic consequences. (Rushkoff has not criticized Covid-19 lockdowns in these terms, as far as I can tell, even though he deftly described “The Mindset” behind them).

In 2020 and 2021, the richest and most powerful huddled in their luxury compounds as they used their influence to shut down large swathes of society and declare a “high-tech war” on the virus.

The world’s ten richest men literally doubled their massive personal fortunes in one year, as did Fauci—“fast money on the crack-up” remember—even as their lockdowns caused economic conditions to crater, undermining everyone’s prospects over the longer term, including their own. Average people suffered the collateral damage of a non-functioning world. Hundreds of millions of people worldwide were pushed into hunger and dire poverty.

In short, a powerful class of panicked elites used lockdowns to seize larger slices of a shrinking pie, and they used technology to keep the masses from getting too rowdy as their slices got smaller. The tech-enabled social controls that regular citizens were subjected to—contact tracing apps, QR codes, vaccine passports, social-media censorship, etc.—served as the sort of technological “disciplinary collar” that the men at Rushkoff’s meeting had dreamed of.

Lockdowns were a perfect expression of The Mindset for handling a major disruption to the global economy that prevails in ultra-elite circles (no, this is not a “conspiracy theory,” it is just how these people think). And like it or not, most of the people in these circles believe that humanity is now faced to one degree or another with the mother of all crises: the “End of Abundance.”

They are looking to a future of lockdowns, mandates, mass surveillance, censorship, underground bunkers, fake meat, factory-farmed bugs, and digital “disciplinary collars” as they “change what it means to be human” and “rebuild the infrastructure of human existence.”

These are not the words, ideas, and plans of confident leaders who believe in a bright future for their people. These are the words, ideas, and plans of self-interested leaders who are preparing to profit from a dystopian future of some kind, and above all to protect themselves.

This is the kind of thinking that attends the decline or collapse of a nation, empire, or civilization. If Western leaders had confidence in a future of robust growth, they would not be trying so furiously to tear down existing social, economic, and cultural arrangements and build them back “Better.”

How to Respond to the “End of Abundance?”

So what is the correct response to the potential “End of Abundance” and the lockdown mentality it has spawned? Right now, there are two general responses.

Those who resisted Covid-19 lockdowns, mostly on the Right, want to beat back the worst excesses of the New Normal. They have been disappointed by the relatively mild political blowback to the Covid fiasco, and ultimately hope for a political movement that will facilitate a return to a golden age of post-World War Two growth, freedom, and the American Dream. The last thing they want to do is give the people who foisted lockdowns on us more power, or adapt to a world of no growth.

Those on the progressive Left who supported lockdowns actually long for a New Normal. They are losing sleep about climate change, Covid-19, new pandemics, worsening inequality, the dreaded MAGAs, and an uncertain future. They are believers in the Brave New World sold to them by the woke technocrats. Progressives believe that future limitations can be overcome if we trust “Experts” and “The Science” and mercilessly punish “Deniers.”

Can either of these strategies prevail? The Right’s strategy of returning to the good ‘ol days neglects the fact that social, economic, and environmental conditions have drastically deteriorated in the last 50 years. This deterioration is precisely why most Western elites and virtually all of the biggest players in the market—Big Tech, Big Pharma, Big Finance, Big Media, Big Ag—have gotten on board with the New Normal, i.e. profiting from some kind of crack-up of the Old Normal.

The Left’s strategy of trusting in new technologies and grand central plans is no more realistic. “Green” energy cannot “solve” climate change because it is probably impossible to convert the world to green energy, or power the economy with it, and attempting to do so would itself cause enormous damage to the planet. All the elaborate technocratic plans for saving the planet—smart cities, cricket cakes, solar farms, sun-reflecting chemical clouds, social credit systems, misinformation task forces, stay-at-home orders—will surely solve nothing and can only bring about a centralized tech-enabled dystopia that primarily benefits elites.

Personally, I am sticking with the view that The Limits to Growth got it pretty much right fifty years ago. Infinite growth on a finite planet is impossible. Nothing can change that. Not “The Science,” not the “Free Market,” not the “Green New Deal,” not the “Great Reset,” not Lockdowns, and not any technology, ideology, grandiose philosophy, or radical scheme. This fundamental reality—the clash between our finite existence and our infinite material ambitions—is why we are in an unprecedented social, economic, and ecological crisis.

And even if I am wrong about that, “The Mindset” of a panicked elite class which no longer believes in a future worth striving for, and which aims primarily to protect itself at the expense of everyone else, virtually ensures societal decline. “Great civilizations die by suicide,” wrote the famed historian Arnold Toynbee, an act that he said was usually committed by a small class of elites who shift from leading to “dominating” everyone else.

So I cannot imagine a lasting return to the Golden Age of growth that conservatives dream of, or the birth of a Brave New World that progressives fantasize about. I think we will all be living in a world that few dream of and even fewer fantasize about: a world of limits.

As Paul Kingsnorth has written, “[w]hatever we think our politics are…we have no idea what to do” about the problem of limits. To the extent any positive outcome is possible, I think it can only emerge from a long, slow process of decentralization. As the global economy strains under the weight of limits, a network of local economies, cultures, and political systems may arise that will serve human needs, and the needs of the planet, better than the centralized dystopia that most Western elites envision.

If some sort of humane decentralized response to a world of limits fails to emerge, we have already had a preview over the last two and a half years of a centralized response to the “End of Abundance.” As Macron put it in his speech, “Freedom has a cost.” He and his allies in the halls of power intend to eliminate that cost from their bottom line. This is their only vision for a future of limits.

But perhaps you feel that all talk about “limits to growth” or the “End of Abundance” is hogwash. Maybe you are convinced that anything less than growth forever and ever is unthinkable. Maybe you believe that the global economy will triple in size over the next three decades and US GDP will smoothly expand from $25 trillion to nearly $75 trillion by 2052 (with a serviceable $140 trillion national debt), as the Congressional Budget Office projects, without any serious damage to the planet or nasty “Fourth Industrial Revolution” to spoil the fun.

Over the long term, regardless of temporary ups and downs, the underlying realities that gave rise to the radical lockdown “Mindset” are not going away. If your understanding of freedom, democracy, and the good life depends on perpetual growth, the constant march of Progress, and ever-rising material standards of living, I hope that you do not eventually find yourself with no choice but to open wide, hold your nose, and eat the bugs.

Better to swallow the bitter reality of limits.

Of course, I could be wrong. Maybe infinite growth on a finite planet is possible, and a return to a golden age of growth is just around the corner.

Brownstone Institute

FDA Exposed: Hundreds of Drugs Approved without Proof They Work

From the Brownstone Institute

By

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved hundreds of drugs without proof that they work—and in some cases, despite evidence that they cause harm.

That’s the finding of a blistering two-year investigation by medical journalists Jeanne Lenzer and Shannon Brownlee, published by The Lever.

Reviewing more than 400 drug approvals between 2013 and 2022, the authors found the agency repeatedly ignored its own scientific standards.

One expert put it bluntly—the FDA’s threshold for evidence “can’t go any lower because it’s already in the dirt.”

A System Built on Weak Evidence

The findings were damning—73% of drugs approved by the FDA during the study period failed to meet all four basic criteria for demonstrating “substantial evidence” of effectiveness.

Those four criteria—presence of a control group, replication in two well-conducted trials, blinding of participants and investigators, and the use of clinical endpoints like symptom relief or extended survival—are supposed to be the bedrock of drug evaluation.

Yet only 28% of drugs met all four criteria—40 drugs met none.

These aren’t obscure technicalities—they are the most basic safeguards to protect patients from ineffective or dangerous treatments.

But under political and industry pressure, the FDA has increasingly abandoned them in favour of speed and so-called “regulatory flexibility.”

Since the early 1990s, the agency has relied heavily on expedited pathways that fast-track drugs to market.

In theory, this balances urgency with scientific rigour. In practice, it has flipped the process. Companies can now get drugs approved before proving that they work, with the promise of follow-up trials later.

But, as Lenzer and Brownlee revealed, “Nearly half of the required follow-up studies are never completed—and those that are often fail to show the drugs work, even while they remain on the market.”

“This represents a seismic shift in FDA regulation that has been quietly accomplished with virtually no awareness by doctors or the public,” they added.

More than half the approvals examined relied on preliminary data—not solid evidence that patients lived longer, felt better, or functioned more effectively.

And even when follow-up studies are conducted, many rely on the same flawed surrogate measures rather than hard clinical outcomes.

The result: a regulatory system where the FDA no longer acts as a gatekeeper—but as a passive observer.

Cancer Drugs: High Stakes, Low Standards

Nowhere is this failure more visible than in oncology.

Only 3 out of 123 cancer drugs approved between 2013 and 2022 met all four of the FDA’s basic scientific standards.

Most—81%—were approved based on surrogate endpoints like tumour shrinkage, without any evidence that they improved survival or quality of life.

Take Copiktra, for example—a drug approved in 2018 for blood cancers. The FDA gave it the green light based on improved “progression-free survival,” a measure of how long a tumour stays stable.

But a review of post-marketing data showed that patients taking Copiktra died 11 months earlier than those on a comparator drug.

It took six years after those studies showed the drug reduced patients’ survival for the FDA to warn the public that Copiktra should not be used as a first- or second-line treatment for certain types of leukaemia and lymphoma, citing “an increased risk of treatment-related mortality.”

Elmiron: Ineffective, Dangerous—And Still on the Market

Another striking case is Elmiron, approved in 1996 for interstitial cystitis—a painful bladder condition.

The FDA authorized it based on “close to zero data,” on the condition that the company conduct a follow-up study to determine whether it actually worked.

That study wasn’t completed for 18 years—and when it was, it showed Elmiron was no better than placebo.

In the meantime, hundreds of patients suffered vision loss or blindness. Others were hospitalized with colitis. Some died.

Yet Elmiron is still on the market today. Doctors continue to prescribe it.

“Hundreds of thousands of patients have been exposed to the drug, and the American Urological Association lists it as the only FDA-approved medication for interstitial cystitis,” Lenzer and Brownlee reported.

“Dangling Approvals” and Regulatory Paralysis

The FDA even has a term—”dangling approvals”—for drugs that remain on the market despite failed or missing follow-up trials.

One notorious case is Avastin, approved in 2008 for metastatic breast cancer.

It was fast-tracked, again, based on ‘progression-free survival.’ But after five clinical trials showed no improvement in overall survival—and raised serious safety concerns—the FDA moved to revoke its approval for metastatic breast cancer.

The backlash was intense.

Drug companies and patient advocacy groups launched a campaign to keep Avastin on the market. FDA staff received violent threats. Police were posted outside the agency’s building.

The fallout was so severe that for more than two decades afterwards, the FDA did not initiate another involuntary drug withdrawal in the face of industry opposition.

Billions Wasted, Thousands Harmed

Between 2018 and 2021, US taxpayers—through Medicare and Medicaid—paid $18 billion for drugs approved under the condition that follow-up studies would be conducted. Many never were.

The cost in lives is even higher.

A 2015 study found that 86% of cancer drugs approved between 2008 and 2012 based on surrogate outcomes showed no evidence that they helped patients live longer.

An estimated 128,000 Americans die each year from the effects of properly prescribed medications—excluding opioid overdoses. That’s more than all deaths from illegal drugs combined.

A 2024 analysis by Danish physician Peter Gøtzsche found that adverse effects from prescription medicines now rank among the top three causes of death globally.

Doctors Misled by the Drug Labels

Despite the scale of the problem, most patients—and most doctors—have no idea.

A 2016 survey published in JAMA asked practising physicians a simple question—what does FDA approval actually mean?

Only 6% got it right.

The rest assumed that it meant the drug had shown clear, clinically meaningful benefits—such as helping patients live longer or feel better—and that the data was statistically sound.

But the FDA requires none of that.

Drugs can be approved based on a single small study, a surrogate endpoint, or marginal statistical findings. Labels are often based on limited data, yet many doctors take them at face value.

Harvard researcher Aaron Kesselheim, who led the survey, said the results were “disappointing, but not entirely surprising,” noting that few doctors are taught about how the FDA’s regulatory process actually works.

Instead, physicians often rely on labels, marketing, or assumptions—believing that if the FDA has authorized a drug, it must be both safe and effective.

But as The Lever investigation shows, that is not a safe assumption.

And without that knowledge, even well-meaning physicians may prescribe drugs that do little good—and cause real harm.

Who Is the FDA Working for?

In interviews with more than 100 experts, patients, and former regulators, Lenzer and Brownlee found widespread concern that the FDA has lost its way.

Many pointed to the agency’s dependence on industry money. A BMJ investigation in 2022 found that user fees now fund two-thirds of the FDA’s drug review budget—raising serious questions about independence.

Yale physician and regulatory expert Reshma Ramachandran said the system is in urgent need of reform.

“We need an agency that’s independent from the industry it regulates and that uses high-quality science to assess the safety and efficacy of new drugs,” she told The Lever. “Without that, we might as well go back to the days of snake oil and patent medicines.”

For now, patients remain unwitting participants in a vast, unspoken experiment—taking drugs that may never have been properly tested, trusting a regulator that too often fails to protect them.

And as Lenzer and Brownlee conclude, that trust is increasingly misplaced.

- Investigative report by Jeanne Lenzer and Shannon Brownlee at The Lever [link]

- Searchable public drug approval database [link]

- See my talk: Failure of Drug Regulation: Declining standards and institutional corruption

Republished from the author’s Substack

Brownstone Institute

Anthony Fauci Gets Demolished by White House in New Covid Update

From the Brownstone Institute

By

Anthony Fauci must be furious.

He spent years proudly being the public face of the country’s response to the Covid-19 pandemic. He did, however, flip-flop on almost every major issue, seamlessly managing to shift his guidance based on current political whims and an enormous desire to coerce behavior.

Nowhere was this more obvious than his dictates on masks. If you recall, in February 2020, Fauci infamously stated on 60 Minutes that masks didn’t work. That they didn’t provide the protection people thought they did, there were gaps in the fit, and wearing masks could actually make things worse by encouraging wearers to touch their face.

Just a few months later, he did a 180, then backtracked by making up a post-hoc justification for his initial remarks. Laughably, Fauci said that he recommended against masks to protect supply for healthcare workers, as if hospitals would ever buy cloth masks on Amazon like the general public.

Later in interviews, he guaranteed that cities or states that listened to his advice would fare better than those that didn’t. Masks would limit Covid transmission so effectively, he believed, that it would be immediately obvious which states had mandates and which didn’t. It was obvious, but not in the way he expected.

And now, finally, after years of being proven wrong, the White House has officially and thoroughly rebuked Fauci in every conceivable way.

White House Covid Page Points Out Fauci’s Duplicitous Guidance

A new White House official page points out, in detail, exactly where Fauci and the public health expert class went wrong on Covid.

It starts by laying out the case for the lab-leak origin of the coronavirus, with explanations of how Fauci and his partners misled the public by obscuring information and evidence. How they used the “FOIA lady” to hide emails, used private communications to avoid scrutiny, and downplayed the conduct of EcoHealth Alliance because they helped fund it.

They roast the World Health Organization for caving to China and attempting to broaden its powers in the aftermath of “abject failure.”

“The WHO’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic was an abject failure because it caved to pressure from the Chinese Communist Party and placed China’s political interests ahead of its international duties. Further, the WHO’s newest effort to solve the problems exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic — via a “Pandemic Treaty” — may harm the United States,” the site reads.

Social distancing is criticized, correctly pointing out that Fauci testified that there was no scientific data or evidence to support their specific recommendations.

“The ‘6 feet apart’ social distancing recommendation — which shut down schools and small business across the country — was arbitrary and not based on science. During closed door testimony, Dr. Fauci testified that the guidance ‘sort of just appeared.’”

There’s another section demolishing the extended lockdowns that came into effect in blue states like California, Illinois, and New York. Even the initial lockdown, the “15 Days to Slow the Spread,” was a poorly reasoned policy that had no chance of working; extended closures were immensely harmful with no demonstrable benefit.

“Prolonged lockdowns caused immeasurable harm to not only the American economy, but also to the mental and physical health of Americans, with a particularly negative effect on younger citizens. Rather than prioritizing the protection of the most vulnerable populations, federal and state government policies forced millions of Americans to forgo crucial elements of a healthy and financially sound life,” it says.

Then there’s the good stuff: mask mandates. While there’s plenty more detail that could be added, it’s immensely rewarding to see, finally, the truth on an official White House website. Masks don’t work. There’s no evidence supporting mandates, and public health, especially Fauci, flip-flopped without supporting data.

“There was no conclusive evidence that masks effectively protected Americans from COVID-19. Public health officials flipped-flopped on the efficacy of masks without providing Americans scientific data — causing a massive uptick in public distrust.”

This is inarguably true. There were no new studies or data justifying the flip-flop, just wishful thinking and guessing based on results in Asia. It was an inexcusable, world-changing policy that had no basis in evidence, but was treated as equivalent to gospel truth by a willing media and left-wing politicians.

Over time, the CDC and Fauci relied on ridiculous “studies” that were quickly debunked, anecdotes, and ever-shifting goal posts. Wear one cloth mask turned to wear a surgical mask. That turned into “wear two masks,” then wear an N95, then wear two N95s.

All the while ignoring that jurisdictions that tried “high-quality” mask mandates also failed in spectacular fashion.

And that the only high-quality evidence review on masking confirmed no masks worked, even N95s, to prevent Covid transmission, as well as hearing that the CDC knew masks didn’t work anyway.

The website ends with a complete and thorough rebuke of the public health establishment and the Biden administration’s disastrous efforts to censor those who disagreed.

“Public health officials often mislead the American people through conflicting messaging, knee-jerk reactions, and a lack of transparency. Most egregiously, the federal government demonized alternative treatments and disfavored narratives, such as the lab-leak theory, in a shameful effort to coerce and control the American people’s health decisions.

When those efforts failed, the Biden Administration resorted to ‘outright censorship—coercing and colluding with the world’s largest social media companies to censor all COVID-19-related dissent.’”

About time these truths are acknowledged in a public, authoritative manner. Masks don’t work. Lockdowns don’t work. Fauci lied and helped cover up damning evidence.

If only this website had been available years ago.

Though, of course, knowing the media’s political beliefs, they’d have ignored it then, too.

Republished from the author’s Substack

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoOttawa Funded the China Ferry Deal—Then Pretended to Oppose It

-

COVID-192 days ago

COVID-192 days agoNew Peer-Reviewed Study Affirms COVID Vaccines Reduce Fertility

-

MAiD2 days ago

MAiD2 days agoCanada’s euthanasia regime is not health care, but a death machine for the unwanted

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoWorld Economic Forum Aims to Repair Relations with Schwab

-

Alberta2 days ago

Alberta2 days agoThe permanent CO2 storage site at the end of the Alberta Carbon Trunk Line is just getting started

-

Alberta1 day ago

Alberta1 day agoAlberta’s government is investing $5 million to help launch the world’s first direct air capture centre at Innisfail

-

Business2 days ago

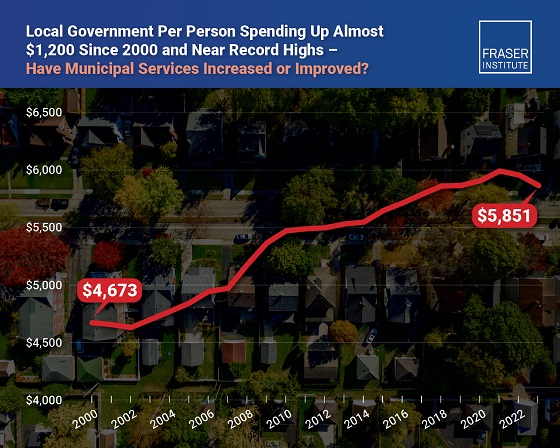

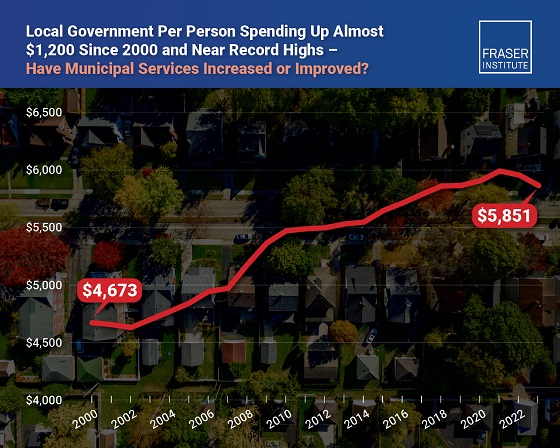

Business2 days agoMunicipal government per-person spending in Canada hit near record levels

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoA new federal bureaucracy will not deliver the affordable housing Canadians need