Community

What is your evidence of performance success?

A few months ago, I made a short essay on the value of understanding the results that mission-based organization has been producing. This is to support the thesis on building management’s capacity to manage their results effectively. What kind of results are your organization producing on a regular basis? Is this adding to your performance story? How can you solidify and have a firm grasp of your results from the interventions that you do with your communities, beneficiaries, and intended audience?

Regardless of the kind of performance the organization is bringing to the table, there is some sort of results/outcomes that get reported to donors, stakeholders, and funders. In this essay, I interchange results with outcomes and vice-versa. This could be:

project-based results – results from project interventions and activities ? strategic outcomes- which come from corporate strategies ? performance outcomes- results that come from the individual performance of employees, performance of departments, or performance on specific task or function ? development results- outcomes that come from identified broad strategic development goals that organizations have set from the beginning, usually aligned to sectoral or national benchmarks

These results form part of the narrative of how the organization has been effective in its mission, how it has articulated its reason for being and how it is using its resources effectively to optimize its relevance for its target audience. And lastly but not the least, how a results mindset increases success for the organization. Most non-profits and mission-based organizations these days have some sort of a results-based management system.

According to Treasury Board of Canada, results-based management is a comprehensive, lifecycle approach to management that integrates strategy, people, resources, processes and measurements to improve decision-making and drive change. The approach focuses on getting the right design early in a process, focussing on outcomes, implementing performance measurement, learning and changing, and reporting performance. Other organizations in a more regulated industry have come up with their own results-driven management systems in place. For small organizations with tiny budgets, few staff and programs running, or a volunteer-run board/committee working on specific activities only, what can the results-based management offer?

1. It offers a solid framework to wrap strategy, resources, people, processes and measurement together. While most RBMs have been used in program and project interventions, it can also be used at the organizational level where no resources, inputs, people can leave unintegrated or fall off the cracks of management.

For example, what can a group of volunteer moms supporting a local daycare or after-school programming think for results? Increased student engagement in after-school programs versus just counting the number of students that attend on a monthly basis.

2. It strengthens the performance story in a seemingly tightening regulatory and accountability demand from donors, funders, and the general public. The intensity, complexity, and stronger (sometimes irrational) demand for evidence puts organization under pressure- to perform, to evaluate their work with rigor, to engage and learn from their innovations. Without an RBM as a framework to set and start this process, organizations will be caught unprepared, ill-equipped and will be scrambling all the time for the next “shiny” object to understand and communicate their results.

No.1 and No.2 have clear implications for management to respond to the call for understanding and organizing their decisions based on results not on outputs. Number of trainings conducted, number of wells built, number of school nutrition program started, number of basketball coaching provided, etc. These are outputs from activities -the trees not the forest.

Are you seeing the forest from the trees? Is your performance story riddled with just stories or actual evidence?

Being mission-based doesn’t mean you do not have the budgets to invest in results-based management. It is just that you do not see it as a priority. This is where the successful organizations are different. They think competence and capacity-building as a priority not as competition to program needs.

If you want success, demonstrate success. And how do you demonstrate success- be results-based, be results-minded. It will save you lots of monies, time, and effort down the road.

Maiden Manzanal-Frank is the Founder, CEO, and President of GlobalStakes Consulting, a consulting organization that provides outstanding results in innovation, impact, and sustainability for companies, social enterprises, non-profits, and international organizations not just in Canada but internationally as well. GlobalStakes Consulting operates in Alberta and BC respectively. You can follow her blogs at www.globalstakesconsulting.com.

Community

Support local healthcare while winning amazing prizes!

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Community

SPARC Caring Adult Nominations now open!

Check out this powerful video, “Be a Mr. Jensen,” shared by Andy Jacks. It highlights the impact of seeing youth as solutions, not problems. Mr. Jensen’s patience and focus on strengths gave this child hope and success.

👉 Be a Mr. Jensen: https://buff.ly/8Z9dOxf

Do you know a Mr. Jensen? Nominate a caring adult in your child’s life who embodies the spirit of Mr. Jensen. Whether it’s a coach, teacher, mentor, or someone special, share how they contribute to youth development. 👉 Nominate Here: https://buff.ly/tJsuJej

Nominate someone who makes a positive impact in the live s of children and youth. Every child has a gift – let’s celebrate the caring adults who help them shine! SPARC Red Deer will recognize the first 50 nominees. 💖🎉 #CaringAdults #BeAMrJensen #SeePotentialNotProblems #SPARCRedDeer

s of children and youth. Every child has a gift – let’s celebrate the caring adults who help them shine! SPARC Red Deer will recognize the first 50 nominees. 💖🎉 #CaringAdults #BeAMrJensen #SeePotentialNotProblems #SPARCRedDeer

-

Alberta11 hours ago

Alberta11 hours agoAlberta Independence Seekers Take First Step: Citizen Initiative Application Approved, Notice of Initiative Petition Issued

-

Crime10 hours ago

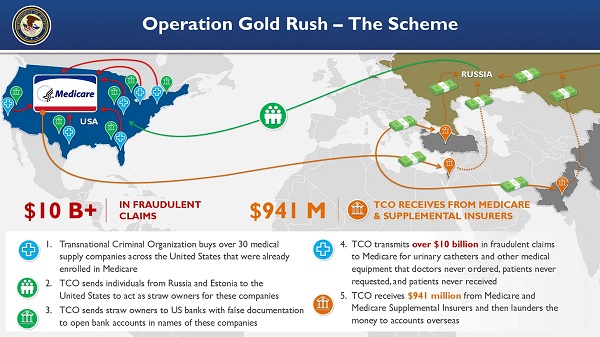

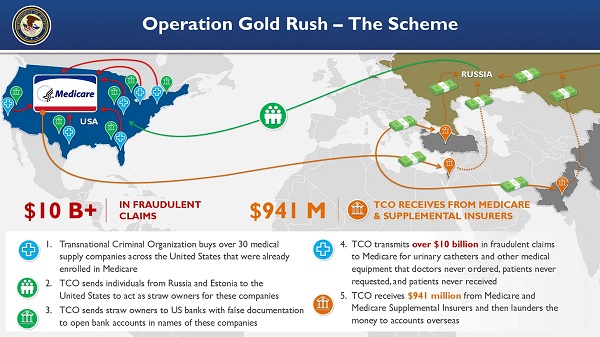

Crime10 hours agoNational Health Care Fraud Takedown Results in 324 Defendants Charged in Connection with Over $14.6 Billion in Alleged Fraud

-

Health9 hours ago

Health9 hours agoRFK Jr. Unloads Disturbing Vaccine Secrets on Tucker—And Surprises Everyone on Trump

-

Bruce Dowbiggin12 hours ago

Bruce Dowbiggin12 hours agoThe Game That Let Canadians Forgive The Liberals — Again

-

Alberta1 day ago

Alberta1 day agoCOVID mandates protester in Canada released on bail after over 2 years in jail

-

Crime2 days ago

Crime2 days agoProject Sleeping Giant: Inside the Chinese Mercantile Machine Linking Beijing’s Underground Banks and the Sinaloa Cartel

-

Alberta2 days ago

Alberta2 days agoAlberta uncorks new rules for liquor and cannabis

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoCanada’s loyalty to globalism is bleeding our economy dry