International

Trump predicts Israel-Hamas ceasefire ‘within the next week’

U.S. President Donald Trump hands a pen to Minister of Foreign Affairs and Cooperation of Rwanda Olivier Nduhungirehe as he meets with Nduhungirehe and the Foreign Minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo Thérèse Kayikwamba Wagner in the Oval Office at the White House on June 27, 2025

From LifeSiteNews

President Trump said the US is sending aid to Gaza as part of a push to end the conflict between Israel and Hamas.

President Donald Trump has predicted a ceasefire between Israel and Hamas in Gaza “within the next week.”

Amid the signing of a peace deal between the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the Republic of Rwanda in the White House’s Oval Office on Friday evening, Trump addressed the “terrible situation” in the Gaza strip and stated that his administration believes “within the next week, we’re going to get a ceasefire.”

President Trump on Gaza: "We think within the next week we're going to get a ceasefire." pic.twitter.com/cWIRGnm963

— CSPAN (@cspan) June 27, 2025

Continuing, the president noted that the U.S. is supplying “a lot of money and a lot of food” to Gaza, “because we have to … because people are dying.”

“We’re doing that because I think we have to on a humanitarian basis,” Trump said.

Touting recent successes in brokering peace globally, Trump boasted, “In a few short months we have now achieved peace between India and Pakistan, Israel and Iran, and the DRC and Rwanda.”

On the conflict between Israel and Iran, the president stressed that the result of American intervention has been that “we ended up with no nuclear weapons,” and that, with the “12-day war” having come to an end, “hopefully there can be a lot of healing … Healing is starting.”

espionage

Trump admin cracks down on China’s silent invasion of U.S. science

Quick Hit:

The Trump administration has launched a sweeping national security investigation into foreign scientists working in U.S. research institutions, targeting those from adversarial countries like China amid fears of espionage and biological threats.

Key Details:

- The probe targets as many as 1,000 foreign scientists inside the NIH alone, focusing heavily on Chinese nationals.

- Intelligence agencies are involved following multiple arrests of Chinese researchers attempting to smuggle dangerous pathogens into the U.S.

- The effort comes after repeated GAO warnings and revelations from a Chinese defector who says Beijing embeds agents in American labs.

Diving Deeper:

The Trump Administration has launched an intensive, behind-the-scenes investigation into hundreds of foreign scientists working in American research institutions—many of them tied to China’s communist regime. According to officials, the review began weeks ago and involves coordination with intelligence and security agencies.

The sweeping audit—prompted by longstanding concerns of foreign influence, espionage, and theft of intellectual property—has zeroed in on nearly 1,000 researchers within the National Institutes of Health (NIH) alone. Most are believed to have gained entry to the U.S. with help from federal research agencies during prior administrations, often without proper vetting.

“The Trump administration is committed to safeguarding America’s national and economic security,” White House spokesman Kush Desai told Just the News. “Taxpayer dollars should not and cannot fund foreign espionage against America’s industrial base and research apparatus.”

That warning is no longer hypothetical. In just the last month, federal officials say three Chinese scientists were arrested attempting to smuggle deadly pathogens into the U.S., including toxic fungi and crop-destroying roundworms—raising fresh fears of agroterrorism.

According to Dr. Li-Meng Yan, a Chinese virologist who defected to the U.S. in 2020, many scientists entering the U.S. from China are effectively agents of the Chinese Communist Party. “They have signed the contract with Chinese government to go back to China, serve for China with whatever they can get from the U.S.,” Yan said. “They become the CCPs’ kind of agents… like the parasites that go into your body.”

Years of inaction from federal agencies are partly to blame. The Government Accountability Office (GAO) has issued more than a half-dozen scathing reports warning that the NIH and partnering universities lack the safeguards to prevent foreign theft of research and influence over scientific projects funded by U.S. taxpayers.

In one 2021 report, GAO bluntly stated that “U.S. research may be subject to undue foreign influence” and cited the NIH’s failure to enforce conflict-of-interest policies, particularly with scientists tied to China.

The crackdown now underway comes amid a surge of related criminal activity. In one case, Chinese scientist Hao Zhang was convicted in 2020 for a scheme dating back to 2006 to steal proprietary semiconductor technology and launch a competing business in China. In another, a cybersecurity professor at Indiana University, Xiaofeng Wang, had his home raided by the FBI earlier this year and was quietly fired, though he has not been charged with any crime.

As part of the broader clampdown, the NIH recently issued new guidance barring researchers from funneling U.S. tax dollars to foreign partners through sub-grants. And the FDA has now halted all trials that export Americans’ cells to labs in hostile nations for genetic engineering—an issue of growing concern.

Congressional allies are backing the administration’s effort, with Rep. Nathaniel Moran (R-Texas) calling for sweeping reforms. “We’ve got to strengthen our own systems from within,” Moran said, “and we’ve got to push back in the trade world, in the tariff world and in the business practices world against China.”

With growing evidence of coordinated foreign espionage and exploitation of U.S. research systems, the administration’s covert operation marks a critical step in defending national security—and could reshape how America handles scientific collaboration for years to come.

Business

The Quiet Invasion: How Transnational Crime and Chinese State Actors Infiltrated Vancouver and Eroded Canada’s Sovereignty

The BC Ferries contract with a Chinese state shipbuilder may not be an anomaly—it appears to be the inevitable product of systematic infiltration dating back to the 1980s.

In the last world war, the Allied assault on the beaches of Normandy marked a decisive turning point in the fight between democracy and tyranny—a massive, kinetic campaign to reclaim territory from a visible enemy. Today, arguably, the battlefield has shifted. Under what Chinese military theorists describe as “unrestricted warfare,” the lines are blurred, the actors are deniable, and the tactics are insidious, incremental, and non-kinetic—at least by traditional definitions.

This war is not waged with tanks or infantry, but through ports, narcotics pipelines, casino floors, telecom servers, banks, law offices, and high-rise real estate towers. If the theory holds—as asserted by senior U.S. and Canadian experts, including former leaders in the State Department and Drug Enforcement Administration—Vancouver may be North America’s longest-standing beachhead in a quiet, protracted invasion. Not kinetic in the traditional sense of bombs falling on North American soil, but no less lethal. This is a conflict marked by the collapse of financial integrity, the erosion of civic life, the use of Canadian financial networks to fund Iran’s nuclear proliferation, and by hundreds of thousands of fentanyl deaths sweeping the continent.

This is the story of how transnational Chinese Triads, state-linked enterprises, Iranian intelligence proxies, and Mexican cartel operatives—working together through encrypted communications and laundering billions, if not trillions, through real estate and shadow banking—systematically infiltrated Canada’s most strategic assets, beginning with the Port of Vancouver.

Over decades, these hybrid networks have corroded governance, captured critical infrastructure, and transformed British Columbia into a central node in a global narco-terror finance system—while Canadian authorities and business leaders hesitated, faltered, looked away, or profited.

Given the evidence detailed below, recent remarks that sparked outrage in Victoria and Ottawa—incendiary interviews on Joe Rogan and Fox News in which FBI Director Kash Patel alleged that Vancouver has become a global hub for fentanyl production and export—shift from incredible to plausible, even provable.

“They’re having the Mexican cartels now make this fentanyl down in Mexico still,” Patel told Rogan, citing classified intelligence, “but instead of going right up the southern border and into America, they’re flying it into Vancouver. They’re taking the precursors up to Canada, manufacturing it up there, and doing their global distribution routes from up there because we’ve been so effective down south.”

Patel described the system as a transnational pipeline linking Chinese Communist Party-associated chemical suppliers and Mexican cartels and Iranian networks, exploiting longstanding weaknesses in Canada’s border enforcement and oversight. The claim drew a public response from British Columbia’s top law enforcement official, Solicitor General Garry Begg, who disputed the allegations.

But Patel went further, stating that Washington believes Beijing is deliberately weaponizing fentanyl to weaken the United States—targeting youth as part of a broader strategy of asymmetric warfare. As The Bureau has reported, this isn’t just the view of a Trump-era Justice official. The same warning was privately conveyed in 2023 to British Columbia’s most outspoken critic of China’s criminal infiltration—Vancouver-area mayor Brad West—by then–Secretary of State Antony Blinken.

Big Circle Beachhead

The infiltration began in the late 1980s—subtle, unrelenting, and state-supported. High-level actors with ties to the Chinese Communist Party embedded themselves in British Columbia’s casinos, ports, and political institutions. By the late 1990s, the network had hardened into a transnational criminal architecture: global smugglers like Lai Changxing—believed by some experts to be a People’s Liberation Army asset—fused elite military corruption and narcotics trafficking in China with violent, militarized gang operations in Vancouver and Toronto.

The earliest and most dangerous of these cells were the Big Circle Boys. Arriving from Hong Kong and Guangzhou in the late 1980s under the guise of refugee claims, they operated not merely as criminal syndicates—but as diaspora enforcers. Like the Mexican cartel operatives of today, they terrorized immigrant communities, treating the human cargo they smuggled into North America as both leverage and profit. Their reputation for extreme violence, deep political corruption, and access to state-grade weapons grew quickly. As Sinaloa gunmen are feared for killing innocents and rivals alike, the Big Circle Boys became infamous for targeting the children of gambling debtors—allegedly taping them to walls and firing bullets around their tiny frames to extract payment, according to Canadian immigration intelligence files from the 1990s.

One of the most feared figures in this network—known to his associates as “Chung Gor”—moved funds across the globe, including between Vancouver and Toronto, alongside Chi Lop Tse, or “Sam Gor,” the Toronto-based chemical narcotics kingpin whom Western law enforcement would later call “Asia’s El Chapo.”

According to intelligence officials, these men were not mere underworld figures. Their operations—shielded by racketeering networks, political proximity in China, and underground banking systems—embodied a form of hybrid warfare: the strategic fusion of organized crime and statecraft, designed to erode Western sovereignty from within.

The archival trail is deeply troubling. A photograph seized during a heroin raid on Chung Gor’s Vancouver residence in the late 1990s shows him standing beside the B.C. NDP Premier—a connection I first revealed in Wilful Blindness (2021). At the time, Chung Gor—translated as “Big Brother Chung”—was identified in a 1998 Canada Border Services Agency intelligence report as a Big Circle “heavyweight,” tied to a Vancouver casino license application.

Raids on his Vancouver properties uncovered semi-automatic firearms, heroin, industrial drug presses, “buckets” of cash, and street narcotics valued in the hundreds of thousands. The CBSA report concluded that Chung Gor’s organization—and more broadly, the Big Circle Boys—functioned as a master of supply-chain logistics for global opioid markets.

“The Asian crime cartel was so powerful that police said it could stockpile heroin and dictate the street price of the drug in North America,” the CBSA document stated. “Its members, who had connections to underground banks in Hong Kong and the poppy fields of Burma, do not hesitate to eliminate obstructions.”

One CBSA intelligence file on a Chung Gor home raid says: “In addition to the stolen goods and weapons, a pound of raw heroin and caches used to stamp heroin for sale stating it was 100 per cent pure” were found and seized.

The file continues: “Vancouver Police Department found and seized a whole bunch of photographs taken of (Chung Gor), including one where (he) was shaking (the BC NDP Premier’s) hand in his office and one where (Chung Gor) was shaking hands or standing with the King of Thailand.”

Despite these links—and resulting heroin charges in B.C. courts—Chung Gor was acquitted in 2002, after a judge ruled that critical wiretap evidence was inadmissible.

Enforcement interest did not end there. In 2006, an RCMP investigation into Asian drug houses across B.C.’s Lower Mainland led officers to an ecstasy lab in a Richmond home where Chung Gor lived with several relatives. They found various chemicals.

He was convicted in 2010 of unlawfully possessing marijuana for the purpose of trafficking, as well as narcotics possession. His sentence: 15 months under conditional supervision. The CBSA’s many efforts to deport him ultimately failed.

Fast-forward two decades, and the pattern repeats—only higher and deeper, politically. Paul King Jin, a central figure in Vancouver’s underground casino laundering ecosystem, a suspected fentanyl trafficker and key associate of Sam Gor, is a frequent traveler to Mexico and Panama. One flight to Mexico linked Jin to the notorious Sam Gor figure “Broken Tooth Koi”—a U.S. Treasury-sanctioned narco who also leads the Chinese Communist Party influence and enforcement group, the Hongmen, widely known for operations aimed at influencing politicians in Canada and other nations with large diaspora populations. Jin has appeared in multiple photographs with senior provincial and federal politicians.

As The Globe and Mail confirmed this year, Jin attended a closed-door event in Richmond where Prime Minister Justin Trudeau met privately with a senior former Chinese official—an alleged Sam Gor affiliate—at a time when RCMP investigators were actively probing the network for casino-linked money laundering.

Tellingly, decades after Chung Gor was photographed beside the BC NDP premier of the day, Canadian enforcement experts say they now possess a photograph showing Chung Gor and the same former Chinese official who met privately with Trudeau and Paul Jin—standing arm in arm, laughing.

According to one Canadian intelligence source, these incidents reflect a deeper threat: that Chinese state-adjacent criminal elites—some of them billionaires—are pursuing a dual objective. Beyond trafficking heroin, fentanyl, ecstasy, and methamphetamine, illegal cannabis and ketamine, and laundering proceeds globally for Mexican cartels, they are systematically cultivating political access in Vancouver, Canada’s most strategically saturated city.

These concerns are explicitly detailed, the source says, in a classified report dated April 16, 2019, prepared by British Columbia’s Joint Illegal Gaming Investigation Team for then–Attorney General David Eby. The document outlines significant corruption risks linked to Chinese transnational crime and describes a growing nexus between organized crime figures and elite actors in British Columbia’s political and business circles.

The Bureau is a reader-supported publication.

To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Port Infiltration and Tech Reconnaissance

By the 1990s, Canadian intelligence and law enforcement agencies had grown increasingly alarmed by the infiltration of the Port of Vancouver by Triads and entities linked to China’s People’s Liberation Army. These concerns are documented in RCMP and CSIS files—most notably in the Sidewinder Report and Project Sunset.

Project Sunset, led by RCMP officer Garry Clement, focused on Hong Kong Triad investments in travel agencies, shopping complexes, financial entities, and port infrastructure in British Columbia as well as real estate in Toronto. Investigators traced phone calls from the Surrey Fraser Docks to known Triad members in Hong Kong—raising major red flags about organized criminal control of supply chain logistics.

The 1997 Sidewinder draft report went further, naming powerful Hong Kong tycoons deeply invested in Vancouver—including Li Ka-Shing, Stanley Ho, and Cheng Yu Tung—and flagging major firms allegedly linked to Chinese intelligence and military fronts. It highlighted state-backed shipping and investment operations as potential platforms for influence and illicit trade.

In December 1999, former Alberta Crown prosecutor Scott Newark wrote to the Security Intelligence Review Committee (SIRC), urging a formal investigation into the abrupt shutdown of Sidewinder. His letter confirmed long-standing intelligence concerns about the penetration of Vancouver’s port by COSCO, a Chinese state-owned shipping giant with alleged ties to both the Triads and the PLA.

Newark also warned that Canada’s decision to dismantle its national Ports Police, under Liberal Prime Minister Jean Chrétien, had dangerously weakened oversight and left the country exposed to foreign criminal syndicates operating through maritime infrastructure.

Newark’s correspondence cited multiple ministerial briefings, including an October 1996 brief prepared for Chrétien’s Transport Minister. His written submission posed a blunt question regarding control of Vancouver’s port:

“Who exactly are the commercial port operators?”

Answering itself, the brief continued:

“We are aware of serious concerns amongst the international law enforcement community surrounding the ownership of ports and container industries in Asia and, in particular, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and the People’s Republic of China.”

The briefing further stated:

“There is simply no longer any doubt that drugs like heroin are coming from these destinations through the Port of Vancouver, moved by organized criminal gangs whose assets include ‘legitimate’ properties.”

Parallel RCMP reporting, including the internal Organized Crime on the Vancouver Waterfront memo, confirmed that the Hells Angels had infiltrated the Longshoreman’s Union, adding to the threat matrix surrounding Vancouver’s port.

Internal SIRC documents reveal that an RCMP Chief Superintendent supported the controversial June 1997 Sidewinder draft. That version explicitly named Li Ka-Shing and flagged major entities such as Hutchison Whampoa Ltd. and China International Trust and Investment Corporation (CITIC)—a state-owned Chinese investment firm. However, CSIS leadership disputed the draft’s conclusions, and in 1999, SIRC determined that CSIS destroyed related files—an action the committee later condemned as an “overly expansive interpretation” of transitory records law.

Reflecting on that era, Garry Clement noted the foresight embedded in Project Sunset.

“Project Sunset was an all-encompassing probe dealing with known Triad personnel traveling and purchasing property primarily in Vancouver, with some in Toronto,” Clement told The Bureau. “The Triads had bundles of money, so they easily met the investment criteria. It was also at this time—when concerns about the Surrey Fraser Docks emerged—that we knew: unless we got our act together, Vancouver would become the transshipment point for transnational organized crime. We were allowing Triads to build the infrastructure.”

While law enforcement was focused on Vancouver’s ports, another Chinese state-aligned infiltration campaign was quietly unfolding across the country—in Canada’s tech capital.

Nortel Networks, once a global telecommunications giant headquartered in Ottawa, became the target of an aggressive intelligence assault—waged by hackers linked to China’s People’s Liberation Army, United Front foreign influence operatives, and state-backed commercial rivals. As early as the late 1990s, Nortel’s systems were deeply compromised, from covert listening devices planted inside its offices to full-scale remote cyber intrusions that siphoned intellectual property in real time.

In 2001, counterfeit Nortel products surfaced in China. By 2004, internal security expert Brian Shields reported that Nortel’s servers were being controlled remotely from China. Over time, key intellectual property was stolen and used to bolster Chinese tech giants—most notably Huawei. Shields said that despite mounting evidence of systemic compromise, Nortel’s senior leadership showed little interest in his warnings.

“The best way to describe it is: between a nation-state, industry, and organized crime, there is cooperation to the point of collaboration and collusion,” one expert told The Bureau. “Spying on Nortel became a requirement that satisfied everyone in that community.”

Former CSIS Asia-Pacific investigator Michel Juneau-Katsuya agreed—and saw the Nortel case as part of a broader campaign of elite influence and systemic betrayal.

“What is missing in the Nortel story is exploring the relationship that has been flagged about all those Nortel leaders going to China for decades,” Juneau-Katsuya said. “I am confident you can see relationships where the United Front will appear in the Nortel case.”

“Nortel is one of those situations where Canada had the lead internationally—and we let it go,” he added. “Why? For one, there were forces within the Canadian government. And Huawei received billions from their government…”

Encryption as Reconnaissance: Tech Fronts, Fentanyl, and the Ortis Betrayal

Beginning around 2007, an encrypted technology front quietly emerged in Vancouver—a development that national security experts now interpret as a reconnaissance operation. It laid the groundwork for hostile foreign state and transnational criminal networks to deepen their hold over Canada’s West Coast economy, particularly its ports and fentanyl supply chains.

The most notorious of these firms would only come into public view years later, following the arrest of former RCMP intelligence director Cameron Ortis, who was charged with leaking top-secret Five Eyes intelligence to transnational crime targets. At the center of this network was Phantom Secure, a Vancouver-based encrypted phone company founded in 2008 from an office in Richmond, B.C. The firm supplied hardened BlackBerry devices to the Sinaloa Cartel, Iranian regime-linked kingpins such as Altaf Khanani, and Chinese Communist Party–aligned criminals.

In 2015, while secretly leaking global investigation plans to cartel-linked targets, Ortis sent an anonymous email to Phantom Secure CEO Vincent Ramos, offering intelligence for money. Ortis’ digital trail would later provide insight into why the U.S. government viewed Phantom Secure and similar Vancouver firms as an urgent threat—and why American agencies sought RCMP assistance to take them down.

According to evidence presented at Ortis’ 2023 national security trial, Ortis requested $20,000 in exchange for classified law enforcement plans targeting Ramos, Khanani, and other Phantom Secure clients.

One recovered message from Ortis to Ramos read:

“Keep in mind that this law enforcement and intelligence agency, they’re cooperating with each other on this, is designed to get to your users and clients (individuals like Polani, Khanani, some cartel members, and so on) by dismantling Phantom Secure.”

One of Ortis’ former RCMP colleagues testified that the criminal network at the heart of these leaks was of profound geopolitical consequence:

“[Khanani’s network] was supporting known terrorist entities, cartels, and the drug trade—it was very significant,” the officer told the court. “It was very clear from what I was seeing that Mr. Ortis wanted to get in touch with Altaf Khanani himself, who was the head of the Khanani Organization, the multi-billion-dollar criminal organization.”

The worldwide investigation into Khanani’s network, including his Canadian ties, was driven by the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration. According to multiple enforcement sources, Hezbollah—designated as a political, military, and criminal proxy of Iran—was using Khanani’s infrastructure to fund Middle East terror operations by laundering drug proceeds for multiple cartels.

Speaking to The Bureau, Dr. David Asher—a former senior Trump administration investigator with the State Department and U.S. Special Operations Command—underscored the significance of the Canadian connection:

“Khanani was one of the top-ten money launderers in the world,” Asher said. “He moved money across Sunni and Shia terrorist organizations. Very few people could launder money for al-Qaeda and also for Hassan Nasrallah [Hezbollah’s leader], and also pick up cartel drug money in Canada and Australia.”

The deeper concern for U.S. officials: Canada’s telecommunications infrastructure and major financial institutions were actively being exploited by Hezbollah and its facilitators. Through telecom companies and high-volume cash schemes in Vancouver, Toronto, and Montreal, billions of illicit dollars were being funneled to weapons programs used by Iran, Hezbollah, and Hamas—including financing nuclear proliferation and military proxies hostile to Western interests.

But Phantom Secure was just one of many similar firms launched in Vancouver.

Around 2008, a second encrypted communications company, referred to here as Company “E”, was established in East Vancouver. According to B.C. court records, in 2009 this firm shared an address with a chemical import business that would soon begin receiving massive precursor shipments from China—including compounds used to manufacture fentanyl, methamphetamine, ecstasy, and LSD.

Two of the firm’s principals were already well known to law enforcement. One was shot and killed in a gang hit near the U.S. border in Surrey in 2013. The other—a member of an Asian organized crime family in Vancouver who later aligned with a major Iranian transnational crime group and the Wolf Pack Alliance, a coalition of Iranian, Asian, and B.C. biker gangsters connected to the Sinaloa Cartel—survived a gang shooting in East Vancouver in 2014, but died the following year of a cocaine overdose.

That same East Vancouver chemical import firm—operating through a shipping container port on the Fraser River in Richmond, a location identified by law enforcement as a Sam Gor transshipment hub—was later named in a British Columbia civil forfeiture case. The filing alleged that, in the years following 2014, the company imported at least 85 tons of chemical precursors used in the production of fentanyl, methamphetamine, ecstasy, and LSD. According to sources, the firm’s networks were deeply entangled with Sam Gor figures and major casino-based laundering activity in British Columbia.

These years—2007 to 2009—marked a tipping point in B.C.’s transformation into a hub of hybrid warfare. It was precisely during this period that the province’s Gaming Policy and Enforcement Branch (GPEB) began documenting a surge in suspicious cash transactions in Lower Mainland casinos, primarily involving Chinese Triad-linked actors tied to Sam Gor. The cash, often delivered late at night in non-uniform bundles of $20 bills by luxury vehicles, would later be described by Justice Austin Cullen in the B.C. Commission of Inquiry into Money Laundering.

Meanwhile, in 2011, Vancouver Police recorded their first confirmed fentanyl seizure, tied to a clandestine lab in East Vancouver, according to public health and law enforcement sources. It marked the beginning of a synthetic opioid wave that would ultimately kill tens of thousands across Canada and the United States—and lay bare the scale of transnational crime’s grip on British Columbia.

A finding from the Cullen Commission’s 2022 report crystallized the convergence of transnational organized crime, fentanyl trafficking, and Chinese capital flight through British Columbia’s casinos. The report documented how, as fentanyl production networks linked to encrypted communications firms and port infiltration exploded in 2014, massive volumes of illicit cash—tied to “whale” gamblers from China—flooded the province’s gaming system.

“Whether they won or lost, they would repay the cash advance to the criminal organization in a form other than cash, often via an electronic funds transfer in another jurisdiction,” the Cullen report stated. “This arrangement enabled wealthy casino patrons to gamble in British Columbia without running afoul of Chinese currency export restrictions, while allowing criminal organizations in B.C. to launder their illicit cash.”

The scale was staggering. In 2014 alone, Justice Cullen found that B.C. casinos accepted nearly $1.2 billion in cash transactions of $10,000 or more—including 1,881 individual buy-ins of $100,000 or more, an average of more than five per day.

The physical characteristics of the cash bore the hallmarks of criminal provenance. Bundles of $20 bills, non-uniform in orientation, bound in elastic bands and “bricks” of fixed dollar value rather than note count, were delivered in shopping bags, gym sacks, suitcases, and cardboard boxes—typically arriving late at night via unmarked luxury vehicles, often at or near the casinos themselves.

As these flows intensified, so did violence within the domestic criminal ecosystem. The deaths of two figures linked to Vancouver’s encrypted communications and chemical importation networks—detailed previously—were not isolated events. A string of high-profile gangland executions, unfolding between 2007 and 2012, marked a brutal power shift. Iranian, Mexican, and Chinese networks consolidated full control. The victims: senior members of once-dominant B.C. trafficking groups.

- October 16, 2010: Gurmit Dhak, co-leader of the Dhak-Duhre gang, is assassinated in broad daylight outside Metrotown Mall in Burnaby.

- August 14, 2011: Jonathan Bacon, a key figure in the Wolfpack Alliance—a coalition of the Red Scorpions, Hells Angels, Independent Soldiers, Iranian criminal actors, and Sinaloa Cartel affiliates—is shot dead at the Delta Grand Hotel in Kelowna.

- January 17, 2012: Sandip “Dippy” Duhre, co-leader of the Dhak-Duhre gang and a longtime rival to the Wolfpack, is killed at the Sheraton Wall Centre in downtown Vancouver.

- April 27, 2012: Tom Gisby, founder of the international Gisby Organization and reputed arms and narcotics trafficker, is gunned down at a Starbucks in Nuevo Vallarta, Mexico.

- November 19, 2012: Sukh Dhak, younger brother to Gurmit is killed in Burnaby.

These killings—professionally executed—stemmed from disputes over control of fentanyl and cocaine supply chains, as well as encrypted communications infrastructure used to protect trafficking routes and launder profits. The net result: the Wolfpack Alliance, closely aligned with Iranian regime operatives, Mexican cartel facilitators, and supplied by Sam Gor–linked precursor networks, emerged as one of the dominant organized crime syndicates in Western Canada.

Critically, the Sam Gor apparatus not only facilitated chemical supply but also laundered proceeds from opioid distribution through United Front–connected underground banking networks across the Western Hemisphere. Within this system, operational failure could be fatal: if a Canadian gangster at the level of Jonathan Bacon or his associates botched a Sinaloa Cartel–supplied narcotics transfer, they risked becoming the target of bombings.

In the years that followed, the warning signs of a narco-state evolution grew more visible. Police raids from the Surrey-Washington border to Prince George uncovered caches of grenades, military-grade firearms, and Mexican passports—all indicators of Sinaloa Cartel entrenchment in British Columbia.

And yet, despite mounting evidence, Canada’s absence of anti-racketeering legislation—such as the U.S. RICO Act—meant that few large-scale prosecutions followed.

Enforcement experts pointed to this legal vacuum—combined with political risk aversion, weak financial crime enforcement, and suspected corruption within senior policing ranks across Canada, including the Cameron Ortis case—as the primary reason high-level operatives walk free or entirely evade investigation.

The Bureau is a reader-supported publication.

To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Maritime Capture: From Xi’s Belt and Road to British Columbia’s Ports

Meanwhile, the expansion of port, shipping, and container infrastructure—the very kind flagged in 1996 by former Alberta prosecutor Scott Newark in a warning letter to Prime Minister Jean Chrétien’s Liberal Transport Minister—has only accelerated.

One example: container and port logistics firms based in Dubai—previously flagged in early 2000s U.S. national security hearings as incompatible with U.S. port ownership—have steadily expanded their presence in Vancouver and northern British Columbia since 2014.

More significantly, Chinese port and shipping influence—specifically the networks flagged by Secretary of State Marco Rubio in Panama—has dramatically deepened in British Columbia since the 1990s. After Xi Jinping came to power, that influence intensified, culminating in a political firestorm over Premier David Eby’s government awarding contracts worth hundreds of millions—reportedly facilitated by a low-interest loan from Liberal Prime Minister Mark Carney’s government, approximately $1 billion—to a state-owned Chinese maritime giant linked to the Belt and Road Initiative and China’s civil‑military fusion strategy.

But outrage over the BC Ferries–China shipbuilding scandal, which raises concerns that the People’s Liberation Army could be effectively funded to develop dual‑use ferry technology useful in potential invasions of Taiwan, may be missing the underlying facts that make this deal appear predetermined.

The pattern escalated in 2013—the year Xi formally launched the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), and Beijing gained observer status at the Arctic Council, signaling growing interest in polar routes and resource corridors. What followed was a decade-long surge in Chinese-linked port access, shipping investment, and industrial cooperation focused on British Columbia.

By 2016, then–B.C. Premier Christy Clark and Trade Minister Teresa Wat had realigned the province’s Pacific Gateway strategy with China’s Belt and Road Initiative. In May of that year, they hosted a high-level “One Belt, One Road” summit in Vancouver and signed a memorandum of understanding with Guangdong Province. Clark’s government proudly declared British Columbia “the first North American jurisdiction to extend the BRI to the continent,” affirming targeted cooperation in maritime trade, shipbuilding, and logistics with Chinese state-owned enterprises.

“During the visit, Premier Clark and Party Secretary Hu discussed opportunities associated with China’s One Belt, One Road Initiative,” a government statement read. “British Columbia and Guangdong will work co-operatively to leverage new and existing transportation partnerships to strengthen the trade capacity of their respective gateway and corridor networks—maritime transportation, shipbuilding and repair, and fisheries and seafood.”

In 2018, Vancouver-based Seaspan acquired Greater China Intermodal (GCI) for approximately US $1.6 billion, adding 18 container vessels—many Chinese-built—to its fleet. A CEO with deep mainland ties took the helm. That same year, Seaspan received a US $1 billion strategic investment and raised additional financing from Asian sources—including Chinese institutions—to fund a major fleet expansion, reportedly involving dozens of Chinese-built ships over the following years.

Despite the 2018 arrest of Huawei CFO Meng Wanzhou in Vancouver, British Columbia remained tightly integrated with China’s maritime economy. Beijing imposed trade restrictions on Canadian seafood and agricultural exports—particularly in Western Canada—demonstrating the economic leverage it had gained.

By 2020–21, as pandemic-era supply chain breakdowns exposed global vulnerabilities, Chinese state media began promoting the “Polar Silk Road,” an Arctic extension of the BRI. Meanwhile, U.S. security analysts sounded increasingly grave warnings. In 2021, a U.S. Navy admiral testified that Chinese shipyards—due to their integration with the People’s Liberation Army—could quickly pivot from commercial vessel construction to military ships. By 2024, a bipartisan U.S. congressional investigation found that one Chinese shipbuilder had produced more commercial tonnage in a single year than the entire U.S. industry had since World War II—triggering calls to decouple Western infrastructure from China’s militarized industrial base.

Nevertheless, in June 2025, the B.C. government awarded its most controversial shipbuilding contract in decades to China Merchants Industry (Weihai)—a major state-owned enterprise embedded in China’s naval‑industrial system—to construct four large hybrid-electric ferries for BC Ferries. The deal, valued at over CA$1 billion with deliveries expected between 2029 and 2031, prompted immediate political backlash. BC Conservative leader John Rustad and MLA Harman Bhangu called for cancellation, warning it handed Beijing a strategic foothold via embedded malware, spyware, and data theft tied to China’s civil-military fusion doctrine.

In a leaked letter, Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland cited security concerns and demanded assurances from British Columbia’s transport minister Mike Farnworth that no federal funds would support the Chinese-built ferries. Yet as The Globe and Mail later revealed, the Canada Infrastructure Bank is in fact providing CA$1 billion in low-interest financing for the project. Internal documents confirm that CA$690 million of that funding is allocated directly to the construction of the vessels.

Posting his own letter yesterday, BC Conservative MLA Harman Bhangu wrote to Freeland expressing outrage that:

“In your recent letter to BC Transportation Minister Mike Farnworth and Premier David Eby, you expressed understandable concern about the selection of a Chinese state-owned shipyard, given China’s punitive tariffs on Canadian goods and ongoing cybersecurity threats. Yet, notably absent from your communication was clarity about the status of the Canada Infrastructure Bank’s substantial financial involvement—specifically whether the $1 billion in low‑interest loans, which includes $690 million directly allocated to the vessels, will continue now that BC Ferries has awarded the contract to a foreign competitor instead of investing in Canada’s robust shipbuilding sector.”

With his posting of the letter to X last night, Bhangu added that “taxpayer dollars should never help outsource Canadian jobs or support shipyards tied to China’s People’s Liberation Army!”

The Bureau is a reader-supported publication.

To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Invite your friends and earn rewards

-

Bruce Dowbiggin5 hours ago

Bruce Dowbiggin5 hours agoWhat Connor Should Say To Oilers: It’s Not You. It’s Me.

-

Business6 hours ago

Business6 hours agoFederal fiscal anchor gives appearance of prudence, fails to back it up

-

Business4 hours ago

Business4 hours agoThe Passage of Bill C-5 Leaves the Conventional Energy Sector With as Many Questions as Answers

-

Alberta2 hours ago

Alberta2 hours agoAlberta poll shows strong resistance to pornographic material in school libraries

-

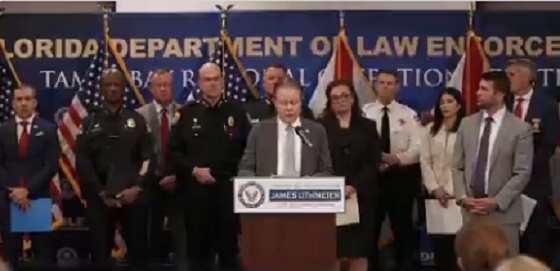

Crime37 mins ago

Crime37 mins agoFlorida rescues 60 missing kids in nation’s largest-ever operation

-

Banks3 hours ago

Banks3 hours agoScrapping net-zero commitments step in right direction for Canadian Pension Plan

-

Alberta2 days ago

Alberta2 days agoAlberta’s government is investing $5 million to help launch the world’s first direct air capture centre at Innisfail

-

armed forces2 days ago

armed forces2 days agoMark Carney Thinks He’s Cinderella At The Ball