Health

Time for an intervention – an urgent call to end “gender-affirming” treatments for children

From the Macdonald Laurier Institute

By J. Edward Les

Despite the Cass Review’s alarming findings, trans activists and their enablers in the medical professions continue to push kids into having dangerous, life-altering surgeries and hormone-blocking treatments. It needs to stop.

If nothing else, the scathing final report of the Cass Review released this week (but commissioned four years ago to investigate the disturbing practices of the UK’s Gender Identity Service), is a reminder that doctors historically are guilty of many sins.

Take the Tuskegee syphilis study, one of the greatest stains on the medical profession, in which impoverished syphilis-infected black men were knowingly deprived of therapy so that researchers could study the natural history of untreated disease.

Or consider the repugnant New Zealand cervical cancer study in the 1960s and 1970s, which left women untreated for years so that researchers could learn how cervical cancer progressed. Or the Swedish efforts to solidify the link between sugar and dental decay by feeding copious amounts of sweets to the mentally handicapped.

The doctors behind such scandals undoubtedly felt they were advancing scientific inquiry in pursuit of the greater good; but they clearly stampeded far beyond the boundaries of ethical medical practice.

More common by far, though, are medical “sins” committed unknowingly, such as when doctors prescribe toxic treatments to patients in the mistaken belief that they are beneficial. When physicians in Europe and Canada latched onto thalidomide in the late 1950s and early 1960s, for instance, they thought it was a wonder drug for morning sickness. Only the fine work of Dr. Francis Kelsey, an astute pharmacist at the FDA, prevented the ensuing birth-defects tragedy from being visited upon American women and children.

And when Oxycontin hit the medical marketplace in the 1990s, physicians embraced it as a marvellous — and supposedly non-addictive — solution to their patients’ pain. But the drug was simply another synthetic derivative of opium, and every bit as addictive; its use triggered a massive opioid overdose crisis — still ongoing today — that has killed hundreds of thousands and ruined the lives of countless individuals and their families.

Physicians in the latter instances weren’t driven by malevolence; but rather by a deep-seated desire to help patients. That wish, compounded by extreme busy-ness, repeatedly seduces doctors into unwarranted faith in untested therapies.

And no discipline in medicine, arguably, is more frequently led astray by the siren song of shiny new things than the field of psychiatry. Which is understandable, perhaps, given the nature of psychiatric practice. Categorizations of mental disorders — and the methods used to treat them — are based almost entirely on consensus opinion, rather than on direct measurement. Contrast that with other domains of medical practice: appendicitis is diagnosed by imaging the infected organ, and then cured by surgically removing the inflamed tissue; diabetes is detected by measuring elevated blood sugar, and then corrected by the administration of insulin; elevated blood pressure is calibrated in millimetres of mercury, and then effectively reduced with antihypertensives; and so on.

But mental disturbances remain largely the stuff of conjecture — learned conjecture, mind you, but conjecture, nonetheless. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, the “bible” of mental health professionals, is the collective effort of groups of tall foreheads gathered around conference tables opining on the various perturbations of the human mind. Imprecise definitions abound, with heaps of overlap between conditions.

The current version (DSM-5) describes schizophrenia, for example, as occurring on a spectrum of “abnormalities in one or more of the following five domains: delusions, hallucinations, disorganized thinking (speech), grossly disorganized or abnormal motor behavior (including catatonia), and negative symptoms.” Each of these five domains is open to professional interpretation; and what’s more, the schizophrenia spectrum is further subdivided into ten sub-categories.

That theme runs through the entire manual – and imprecise definitions lead on to imprecise solutions. Given the blurred indications for starting, balancing, and stopping medications, it’s no accident that many mentally unwell patients languish on ever-changing cocktails of mind-altering drugs.

None of which is to downplay the enormous importance of psychiatry, which does much to address human suffering amidst unimaginable complexity; its practitioners are among the brightest and most capable members of the medical profession. But by its very nature the discipline is submerged in — and handicapped by — uncertainty. It’s unsurprising, then, that mental health professionals desperate for effective treatments are susceptible to being misled.

The dark history of frontal lobotomies, seized upon by psychiatrists as a miracle cure but long relegated to the trash heap of medical barbarism, is well known. The procedure (which garnered its inventor the Nobel Prize in Medicine) basically consisted of driving an ice pick through patients’ eye sockets to destroy their frontal lobes; thousands of patients were permanently maimed before saner heads prevailed and the practice was halted. Many of its victims were gay men: “conversion therapy” with a literal, brain-altering “punch.”

Similarly, the fabricated “recovered memories of sexual abuse” saga of the 1980s and early 1990s suckered mental health practitioners into believing it was legitimate. Hundreds of professional careers were built on the “therapy” before it was all exposed as a fraud, leaving many lives ruined, families torn asunder, and scores of innocent men imprisoned or dead from suicide. In a 2005 review, Harvard psychology professor Richard McNally pegged the recovered memory movement as “the worst catastrophe to befall the mental health field since the lobotomy era.”

Until now, that is. That scandal pales in comparison to the “gender transition/gender affirming care” craze that has befogged the medical profession in recent years.

Without a shred of supporting scientific evidence, many doctors — led by psychiatrists, but aided and abetted by endocrinologists, surgeons, pediatricians, and family doctors — have bought into the mystical notion of gender fluidity. What was previously recognized as “gender identity disorder” was rebranded as gender “dysphoria” and recast as part of the normal spectrum of human experience, the basic truth of binary mammalian biology simply discarded in favour of the fiction that it’s possible to convert from one sex to another.

Much suffering has ensued. The enabling of biological males’ invasion of women’s spaces, rape shelters, prisons, and sports is bad enough. But what is being done to children is the stuff of horror movies: doctors are using medications to block physiological puberty as prologue to cross-gender hormones, genital-revising surgery, and a lifetime of infertility and medical misery — and labelling the entire sordid mess as gender-affirming care.

The malignant fad began innocently enough, with a Dutch effort in the late 1980s and early 1990s to improve the lot of transgendered adults troubled by the disconnect between their physical bodies and their gender identity. Those clinicians’ motivations were defensible, perhaps; but their research was riddled with ethical lapses and methodological errors and has since been thoroughly discredited. Yet their methods “escaped the lab”, with the international medical community adopting them as a template for managing gender-confused children, and the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) enshrining them as “standard of care.” Then, as American social psychologist Jonathan Haidt is the latest to observe, the rise of social media torqued the trend into a craze by convincing hordes of adolescents they were “trans.” Which is how we ended up where we are today, with science replaced by rabid ideology — and with condemnation heaped upon anyone who dares to challenge it.

An explanation sometimes offered for the massive spike in gender-confused kids seeking “affirmation” in the past fifteen years is that today it’s “safe” for kids to express themselves, as if this phenomenon always existed but that — as with homosexuality — it was “closeted” due to stigma. Yet are we really expected to believe that the giants of empirical research into childhood development —brilliant minds like Jean Piaget, Eric Erikson, Lev Vygotsky, and Lawrence Kohlberg — somehow missed entirely the trait of mutable “gender identity” amongst all the other childhood traits they were studying? That’s nonsense, of course. They didn’t miss it — because it isn’t real.

The fog is beginning to dissipate, thankfully. Multiple jurisdictions around the world, including the UK, Sweden, Norway, Finland, and France have begun to realize the grave harm that has been done, and are pulling back from — or halting altogether — the practice of blocking puberty. And the final Cass Report goes even further, taking square aim at the dangerous practice of social transitioning and concluding that it’s “not a neutral act” but instead presents risk of grave psychological harm.

All of which places Canada in a rather awkward position. Because in December of 2021 parliamentarians gave unanimous consent to Bill C-4, which bans conversion therapy, including “any practice, service or treatment designed to change a person’s gender identity.” It’s since been a crime in Canada, punishable by up to five years in prison, to try to help your child feel comfortable with his or her sex.

As far as I know, no one has been charged, let alone imprisoned, since the bill was passed into law. But it certainly has cast a chill on the willingness of providers to deliver appropriate counselling to gender-confused children: few dare to risk it.

A conversion therapy ban had been in the works for years, triggered by concerns about disturbing and harmful practices targeting gay children. But by the time the bill was presented in its final form to Parliament for a vote it had been hijacked by trans activists, with its content perverted to the degree that there is more language in the legislation speaking to gender identity than to homosexuality.

To be clear, likening homosexuality to pediatric “gender fluidity” is a category error, akin to comparing apples to elephants. The one is an innate sexual orientation, the acceptance of which requires simply leaving people be to live their lives and love whomever they wish; the other is wholly imaginary, the acceptance of which mandates irreversible medical (and often surgical) intervention and the transformation of children into lifelong (and usually infertile) medical patients.

And the real “elephant” in the room is that in a troubling number of cases pediatric trans care is conversion therapy for gay children because for some people, it’s more acceptable to be trans than it is to be gay.

Bill C-4 received unanimous endorsement from all parliamentarians, including from Pierre Poilievre, now the leader of the Conservative Party. No debate. No analysis. Just high-fives all around for the television cameras.

It’s possible that many of the opposition MPs hastening to support the ban did so for fear of being painted as bigots. Yet the primary responsibility of an opposition party in any healthy democracy is to oppose, even when it’s unpopular. In 2015, when NDP Opposition leader Tom Mulcair faced withering criticism for resisting anti-terror legislation tabled by Stephen Harper’s Conservative government, he cited John Diefenbaker’s comments on the role of political opposition:

“The reading of history proves that freedom always dies when criticism ends… The Opposition finds fault; it suggests amendments; it asks questions and elicits information; it arouses, educates, and moulds public opinion by voice and vote… It must scrutinize every action of the government and, in doing so, prevents the shortcuts through democratic procedure that governments like to make.”

In the case of Bill C-4 the Conservatives did none of that. And by abdicating their responsibility they helped drive a metaphorical ice pick into the futures of scores of innocent children, destroying forever their prospects for normal, healthy lives.

We’re long overdue for a “conversion”: a conversion back to the light of reason, a conversion back to evidence-based care of children.

In 1962, when the harms of thalidomide became known, it was withdrawn from the Canadian market. In 2024, now that the serious harms of “gender-affirming care” have been exposed, it remains an open question as to when Canada’s doctors and politicians will finally take the difficult step of admitting that they got it wrong and put a stop to the practice.

Dr. Edward Les is a pediatrician in Calgary who writes on politics, social issues, and other matters.

Health

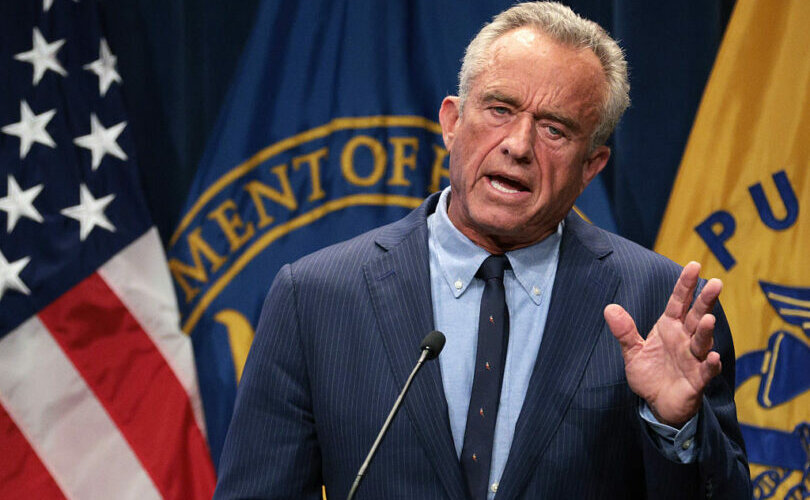

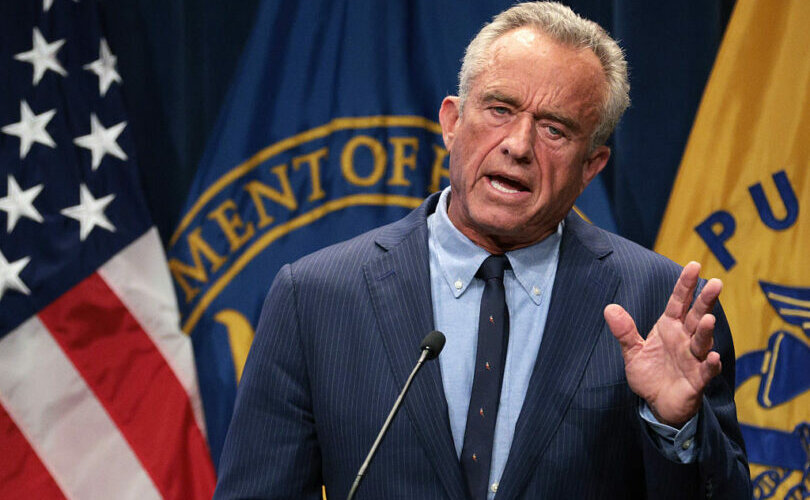

RFK Jr. purges CDC vaccine panel, citing decades of ‘skewed science’

From LifeSiteNews

By Robert Jones

RFK Jr.’s HHS has removed all Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices members in an effort to reset public confidence in vaccine oversight.

Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. has dismissed every member of the CDC’s top vaccine advisory panel, citing what he described as a “decades” of “conflicts of interest” and “skewed science” in the vaccine regulatory system.

RFK Jr.’s abrupt decision to “retire” all 17 members of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) was announced in a Wall Street Journal op-ed Monday and confirmed by HHS shortly thereafter.

The move marks the most sweeping reform to federal vaccine policy in years and follows months of internal reviews and mounting public skepticism.

Kennedy accused the ACIP of being “little more than a rubber stamp for any vaccine,” claiming “it has never recommended against a vaccine.”

“The public must know that unbiased science guides the recommendations from our health agencies,” Kennedy wrote. “This will ensure the American people receive the safest vaccines possible.”

ACIP holds the power to influence which vaccines are recommended by the CDC and covered by insurers. But according to Kennedy, it has failed in its duty to protect the public.

He cited multiple government investigations—dating back to 2000 and 2009—finding that ACIP members were routinely advising on products from pharmaceutical firms with which they had financial ties. Committee members were also issued conflict-of-interest waivers from the CDC.

Kennedy pointed to the 1997 vote approving the Rotashield vaccine – later withdrawn for causing severe bowel obstructions in infants – as a case study in regulatory failure. Four of the eight members who voted for it had financial stakes in rotavirus vaccines under development.

He explained “retiring” the 17 members, “some of whom were last-minute appointees of the Biden administration,” by saying that without such a move, “the Trump administration would not have been able to appoint a majority” until 2028.

CNBC warned the firings could “undermine vaccinations” and erode trust among scientists. But Kennedy, a longtime vaccine industry sceptic, maintains that trust has already “collapsed” – and that restoring it requires nothing less than a full reset.

Under Kennedy’s leadership, HHS has already halted recommendations for routine COVID-19 shots for healthy children and pregnant women and cancelled COVID-era programs to fast-track new vaccines.

It remains unclear who will replace the outgoing ACIP members, though HHS confirmed the committee will still meet later this month, now under new leadership.

“The new members won’t directly work for the vaccine industry,” he promised. “They will exercise independent judgment, refuse to serve as a rubber stamp, and foster a culture of critical inquiry—unafraid to ask hard questions.”

Health

Police are charging parents with felonies for not placing infants who died in sleep on their backs

From LifeSiteNews

By Dr. Brenda Baletti, The Defender

Pennsylvania authorities brought felony charges against the parents of two different babies after police said the infants died because the parents placed them in unsafe sleeping positions.

Parents of two different babies are being charged with felonies in Pennsylvania after police say their babies died because the parents placed them in unsafe sleeping positions, SpotlightPA reported.

In both cases, police allege that the parents failed to follow guidance, including handouts given to them at doctor’s visits, stating that babies should be put to sleep on their backs.

Gina and David Strause of Lebanon County are accused of putting their 3-month-old infant son, Gavin, to sleep on his stomach and allowing him to sleep with stuffed animals in the crib.

They are charged with involuntary manslaughter, recklessly endangering another person, and endangering the welfare of children.

Natalee Rasmus of Luzerne County is accused of putting her 1-month-old daughter, Avaya Jade Rasmus-Alberto, to sleep on her stomach on a boppy pillow, often used for nursing. She is charged with third-degree murder, involuntary manslaughter, and endangering the welfare of children.

Rasmus was a 17-year-old mother when her daughter died in 2022. Court records show that she continues to be held at the Luzerne County Correctional Facility with bail set at $25,000 pending resolution of her case.

In both cases, autopsies concluded the babies died of accidental death from asphyxiation. Law enforcement argued in both cases that parents should have known that putting the babies to sleep on their stomachs was unsafe, because they had received paperwork at wellness visits informing them of safe sleeping practices.

They pointed to signed acknowledgements in the babies’ medical records that were created as part of a 2010 state law to educate parents about Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS).

The law requires hospitals, birthing centers, and medical providers to give parents educational materials from the national Safe to Sleep campaign, and ask them to certify that they received them.

Signing the statement is voluntary. The statement doesn’t indicate that parents can be charged with a criminal offense if they don’t follow the campaign advice.

Advocates from national organizations that educate parents about safe sleep practices found the charges shocking. Nancy Maruyama, the executive director of Sudden Infant Death Services of Illinois, told Spotlight PA, “To charge them criminally is a crime, because they have already suffered the worst loss.”

Alison Jacobson, executive director of First Candle, a non-profit that also educates parents about safe sleep practices, told Pennlive, “There is no law against placing a baby on his or her stomach to sleep. How they can charge this family with involuntary manslaughter is completely baffling to me.”

Researcher Neil Z. Miller, an expert on SIDS and the Safe to Sleep campaign, told The Defender, “Parents of a sleeping baby who dies in the middle of the night should never be charged with murder. That’s just cruel.”

Miller, author of “Vaccines: Are They Really Safe and Effective?” added:

Should parents be obligated to follow every “recommendation” made by their doctor or the Safe to Sleep campaign? Would we as a society prefer that doctors raise our babies instead of the parents? Have other possible causes of death been considered, such as vaccinations? As a society, we can, and must, do much better.

Does placing infants on their backs make a difference?

The handouts shared with new Pennsylvania parents are based on the National Institutes of Health “Safe to Sleep” campaign, which institutionalized a program initiated by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) in 1992 to inform parents to put children to sleep on their backs rather than on their stomachs.

The campaign is based on the premise that babies who sleep on their backs or sides are less likely to die in their sleep. Until that time, it was common for babies to sleep on their stomachs.

The program was launched in the wake of a rising number of SIDS deaths – and growing concern among some parents that the deaths were linked to vaccination.

In a 2021 article in the peer-reviewed journal Toxicology Reports, vaccine researcher Neil Z. Miller provides a history of the SIDS diagnosis, noting that the rise of SIDS coincided with the first mass immunization campaigns.

Between 1992, when the Safe to Sleep program launched, and 2001, SIDS deaths reportedly declined a whopping 55 percent – a number touted in articles celebrating the program, making it appear that babies sleeping on their stomachs was the cause of SIDS, not vaccines.

However, at the same time deaths from SIDS decreased, the rate of mortality from “suffocation in bed,” “suffocation other,” “unknown and unspecified causes,” and “intent unknown” all increased significantly.

Why? The classification system had changed. SIDS deaths were being reclassified by medical certifiers, usually coroners, as one of the other similar categories, not SIDS.

Research published in the journal Pediatrics, the AAP’s flagship journal, concluded that deaths previously certified as SIDS were simply being certified as other non-SIDS causes, such as suffocation – but the deaths were still essentially SIDS deaths.

That change in classification accounted for more than 90 percent of the drop in SIDS rates.

The Pediatrics paper showed no decline in overall postneonatal mortality after the Safe to Sleep campaign was launched, despite the program’s – and the AAP’s – claims to the contrary.

Others verified the Pediatrics paper’s findings, and the trend continued, as reported by multiple studies in top journals. Miller reported that, for example, “From 1999 through 2015, the U.S. SIDS rate declined 35.8% while infant deaths due to accidental suffocation increased 183.8%.”

Research shows that almost 80 percent of SIDS deaths reported to the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) happen within seven days of vaccination.

Theories linking vaccines to SIDS suggest that, in some cases, underdeveloped liver enzyme pathways may make it harder for some infants to process toxic ingredients in vaccines. Others argue that other, multiple, complex factors can make some infants vulnerable to toxic ingredients in vaccines.

Baby Gavin was ‘a dream come true’

On April 30, Gina and David Strause were charged with involuntary manslaughter, which carries a sentence of up to 10 years, and other lesser charges in the death of their son, Gavin.

According to the police report, Gina found her son unresponsive, cold, and blue in his crib when she woke up to feed him on the morning of May 8, 2024. She immediately called 911 and performed CPR until the police arrived.

The baby was pronounced dead at the hospital. The autopsy report found the cause of death to be “complications of asphyxia.”

Police said they observed loose items in the crib, “such as blankets and stuffed animals.”

Gina said that after feeding her baby at about 11:30 p.m. the night before he died, she placed him in his crib on his belly, because he was a “belly sleeper,” and covered him with a blanket. She said that she had received the recommendation that he should sleep on his back, but that he preferred to sleep on his stomach.

In an interview with Pennlive, Gina said that she typically put Gavin to sleep on his back, but he had gotten into the daily habit of rolling onto his belly.

Davis Stause told police that when he left for work at 5:30 a.m., he checked on Gavin, who was sleeping on his stomach and moving around a little bit. David said he “patted his butt” to put him back to sleep.

The police reported that they also obtained medical records from birth through death that showed that on the discharge paperwork that the parents received information about safe sleep practices, which included putting the baby on its back, having it sleep in the same room as the parents, and keeping the crib clear of bumper pads and stuffed animals.

They said this paperwork explained how parents could create a safe sleeping environment for their babies to reduce the risk of SIDS.

Baby Gavin also went to the pediatrician for well-child visits on February 7 and 14, March 5, and April 9, a month before he died.

Gina told Pennlive that Gavin, who was born when she was almost 40, was “a dream come true.” She had taken 10 weeks of maternity leave and largely worked at home to spend as much time with him as possible. She said that after she gave birth, she was “overwhelmed” and didn’t remember receiving any paperwork or instructions about sleep.

Gina also said that at the hospital, police treated her and her husband with immediate suspicion, separating and questioning them. They were not allowed to see their baby again before he was taken by the coroner’s office.

The parents created a GoFundMe page, where they shared a copy of the police report, to help cover their legal costs, because they said they do not qualify for a public defender.

The Defender attempted to contact the parents to inquire about the baby’s overall health, if he had any medical conditions, was born prematurely, or had recently received any vaccines, but the parents did not respond by deadline.

The district attorney’s office also did not respond to requests for comment.

‘Tragic accident with no criminal intent to harm or kill the baby’

The forensic pathologist who performed the autopsy for Natalee Rasmus’ baby listed the cause of death as accidental. According to the report, the baby died from asphyxiation, the Times Leader reported.

Rasmus discovered her baby had died on the morning of October 23, 2022, when she picked her up to get her ready for a doctor’s appointment.

Pennsylvania State Police in December charged Rasmus, alleging that she placed her baby face down to sleep against the recommendations of medical personnel and prenatal classes at Geisinger Wyoming Valley Medical Center.

At a preliminary hearing on the case in February, a state trooper testified that Rasmus ignored safe sleeping practices because she had placed her baby face down in her bassinet with a Boppy pillow, which has a tag warning, “Do not use for sleeping.”

The trooper, Caroline Rayeski, also testified that a search of Rasmus’ cell phone found that she had searched the internet to see whether it was ok to allow newborns to sleep on their stomachs. The trooper also seized literature from the prenatal classes stating it is “recommended” to put newborns to sleep on their backs.

“Yeah, she wouldn’t sleep, she’ll just scream, so she has to be like propped up,” Rasmus told the investigating officer, according to Spotlight PA, which reported the story.

Assistant attorneys argued in a preliminary hearing that she disregarded safe sleeping practices, and a judge forwarded the criminal case to county court.

Rasmus is being represented by public defenders Joseph Yeager and Melissa Ann Sulima, who told the Times Leader the baby’s death was “a tragic accident with no criminal intent to harm or kill the baby.”

Yeager said the prenatal literature referring to newborn sleep positions are “recommendations,” not mandates.

“As the death certificate says, it was an accident. Clearly, there was no malice in this accidental death,” said Yeager, who also said the case should be dismissed.

Rasmus’ most serious charge, third-degree murder, is a homicide that involves killing someone without intent to kill, but with reckless disregard for human life. In Pennsylvania, it can carry a prison sentence of up to 40 years.

Court documents indicate that Rasmus remains in jail with a $25,000 bail, pending the outcome of her case. Neither the district attorney nor Rasmus’ attorneys responded to The Defender’s request for comment.

How common is it to bring criminal charges against parents in infant deaths?

Attorney Daniel Nevins told SpotlightPA it is extremely rare for parents to be criminally charged when infants die after sleeping on their stomachs, and that the burden of proof on the prosecutors will be high.

In 2014, Virginia resident Candice Christa Semidey, age 25, was charged with murder after she swaddled her baby and put it to sleep on its stomach, the Washington Post reported. In that case, police similarly did not think that she intended for the baby to die.

She pleaded guilty to involuntary manslaughter and child neglect. She was ordered to serve three years of probation to avoid the five-year prison term she was sentenced to.

Some charges have also been brought against parents in deaths of infants sleeping with Boppy pillows. There have also been several cases of parents charged for sleeping in the same bed as their child.

The Defender recently reported on three SIDS deaths that occurred shortly after vaccination. Police are still investigating the parents of 18-month-old twins who died together a week after receiving three vaccines. Authorities have not yet charged the parents, but initially said they were investigating the deaths as homicides.

Blessings Myrical Jean Simmons, age 6 months, received six routine vaccines at a well-baby visit on January 13. The next morning, her parents found the baby dead in her bassinet. The autopsy lists SIDS as the infant’s cause of death, and no charges were filed against the parents.

This article was originally published by The Defender — Children’s Health Defense’s News & Views Website under Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Please consider subscribing to The Defender or donating to Children’s Health Defense.

-

Crime1 day ago

Crime1 day agoHow Chinese State-Linked Networks Replaced the Medellín Model with Global Logistics and Political Protection

-

Addictions1 day ago

Addictions1 day agoNew RCMP program steering opioid addicted towards treatment and recovery

-

Aristotle Foundation2 days ago

Aristotle Foundation2 days agoWe need an immigration policy that will serve all Canadians

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoNatural gas pipeline ownership spreads across 36 First Nations in B.C.

-

Courageous Discourse1 day ago

Courageous Discourse1 day agoHealthcare Blockbuster – RFK Jr removes all 17 members of CDC Vaccine Advisory Panel!

-

Health1 day ago

Health1 day agoRFK Jr. purges CDC vaccine panel, citing decades of ‘skewed science’

-

Business14 hours ago

Business14 hours agoEU investigates major pornographic site over failure to protect children

-

Censorship Industrial Complex1 day ago

Censorship Industrial Complex1 day agoConservatives slam Liberal bill to allow police to search through Canadians’ mail