Frontier Centre for Public Policy

The Smallwood solution

From the Frontier Centre for Public Policy

All Canadians deserve decent housing, and indigenous people have exactly the same legal right to house ownership, or home rental, as any other Canadian. That legal right is zero.

$875,000 for every indigenous man, woman and child living in a rural First Nations community. That is approximately what Canadian taxpayers will have to pay if a report commissioned by the Assembly of First Nations (AFN) is accepted. According to the report 349 billion dollars is needed to provide the housing and infrastructure required for the approximately 400,000 status Indians still living in Canada’s 635 or so First Nations communities. ($349,000,000,000 divided by 400,000 = ~$875,000).

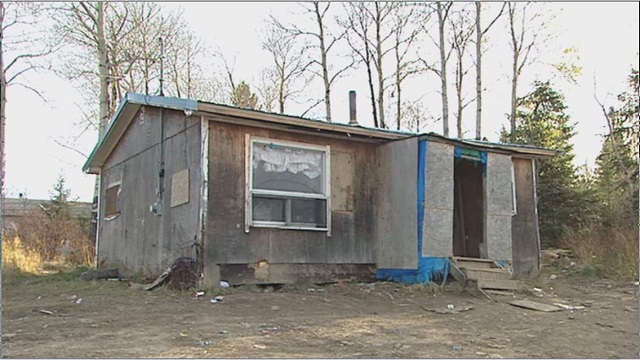

St Theresa Point First Nation is typical of many of such communities. It is a remote First Nation community in northern Manitoba. CBC recently did a story about it. One person interviewed was Christina Wood, who lives in a deteriorating house with 23 family members. Most other people in the community live in similar squalor. Nobody in the community has purchased their own house, and all rely on the federal government to provide housing for them. Few people in the community have paid employment. Those that do have salaries that come in one way or another from the taxpayer.

But St. Theresa Point is a growing community in the sense that birth rates are high, and few people have the skills or motivation needed to be successfully employed in Winnipeg, or other job centres. Social pathologies, such as alcohol and other drug addictions are rampant in the community. Suicide rates are high.

St. Theresa Point is one of hundreds of such indigenous communities in Canada. This is not to say that all such First Nations communities are poor. In fact, some are wealthy. Those lucky enough to be located in or near Vancouver, for example, located next to oil and gas, or on a diamond mine do very well. Some, like Chief Clarence Louis’ Osoyoos community have successfully taken advantage of geography and opportunity and created successful places where employed residents live rich lives.

Unfortunately, most are not like that. They look a lot more like St. Theresa Point. And the AFN now says that 350 billion dollars are needed to keep those communities going.

Meanwhile, all of Canada is in the grip of a serious housing crisis. There are many causes for this, including the massive increase in new immigrants, foreign students and asylum seekers, all of whom have to live somewhere. There are various proposals being considered to respond to this problem. None of those plans come anywhere near to suggesting that $875,000 of public funds should be spent on every Canadian man, woman or child who needs housing. The public treasury would not sustain such an assault.

All Canadians deserve decent housing, and indigenous people have exactly the same legal right to house ownership, or home rental, as any other Canadian. That legal right is zero. Our constitution does not give Canadians – indigenous or non-indigenous- any legal right to publicly funded home ownership, or any right to publicly funded rental property. And no treaty even mentions housing. In all cases it is assumed that Canadians – indigenous and non-indigenous – will provide for themselves. This is the brutal reality. We are on our own when it comes to housing. There are government programs that assist low income people to buy or rent homes, but they are quite limited, and depend on a person qualifying in various ways.

But indigenous people do not have any preferred right to housing. The chiefs and treaty commissioners who signed the treaties expected indigenous people to provide for their own housing in exactly the same way that all other Canadians were expected to provide for their own housing. In fact, the treaty makers, chiefs and treaty commissioners – assumed that indigenous people would support themselves just like every other Canadian. There was no such thing as welfare then.

Our leaders today face difficult decisions about how to spend limited public funds to try and help struggling Canadians find adequate housing in which to raise their families, and get to and from their places of employment. Indigenous Canadians deserve exactly as much help in this regard as everyone else. Finding sensible, affordable ways to do this is vitally important if Canada is to thrive.

And one of hundreds of these difficult and expensive housing decisions our leaders must deal with now is how to respond to this new demand for 350 billion dollars – a demand that would result in indigenous Canadians receiving hundreds of times more housing help than other Canadians.

Our leaders know that authorising massive spending like that in uneconomic communities is completely unfair to other Canadians – for one thing doing so means that there would be no money left for urban housing assistance. They also know that pouring massive amounts of money into uneconomic, dysfunctional communities like St. Theresa’s Point – the “unguarded concentration camps” Farley Mowat described long ago- only keeps generations of young indigenous people locked in hopeless dependency.

In short, they know that the 350 billion dollar demand makes no sense.

Our leaders know that, but they won’t say that. In fact it is not hard to predict how politicians will respond to the 350 billion dollar demand. None of their responses will look even remotely like what I have written above. Instead, they will say soothing things, while pushing the enormous problem down the road. Eventually, when forced by circumstances to actually make spending decisions they will provide stopgap “bandage” funding. And perhaps come up with pretend “loan guarantee” schemes – loans they know will never be repaid. Massive loan defaults in the future will be an enormous problem for our children and grandchildren. But today’s leaders will be gone by then.

So, in a decade or so communities, like St. Theresa Point, will still be there. Any new housing that has been built will already be deteriorating and inadequate. The communities will remain dependent. The young people will be trapped in hopeless dependency.

And the chiefs will be making new money demands.

At some point this country will have to confront the reality that most of Canada’s First Nations reserves, particularly the remote ones, are not sustainable. Better plans to educate and provide job skills to the younger generations in those communities, and assist them to move to job centres, will have to be found. Continuing to pretend that this massive problem will sort itself out by passing UNDRIP legislation, or pretending that those depressed communities are “nations” is only delaying the inevitable.

When Joey Smallwood told the Newfoundland fishermen, who had lived in their outports for generations, that they must move for their own good, there was much pain. But the communities could no longer support themselves, and it had to be done. Entire communities moved. It worked out.

The northern First Nations communities are no different. The ancestors of the residents of those communities supported themselves by fishing and hunting. It was an honourable life. But it is gone. The young people there now will have to move, build new lives, and become self-supporting like their ancestors.

Brian Giesbrecht, retired judge, is a Senior Fellow at the Frontier Centre for Public Policy

Business

Ottawa Is Still Dodging The China Interference Threat

From the Frontier Centre for Public Policy

By Lee Harding

Alarming claims out of P.E.I. point to deep foreign interference, and the federal government keeps stalling. Why?

Explosive new allegations of Chinese interference in Prince Edward Island show Canada’s institutions may already be compromised and Ottawa has been slow to respond.

The revelations came out in August in a book entitled “Canada Under Siege: How PEI Became a Forward Operating Base for the Chinese Communist Party.” It was co-authored by former national director of the RCMP’s proceeds of crime program Garry Clement, who conducted an investigation with CSIS intelligence officer Michel Juneau-Katsuya.

In a press conference in Ottawa on Oct. 8, Clement referred to millions of dollars in cash transactions, suspicious land transfers and a network of corporations that resembled organized crime structures. Taken together, these details point to a vulnerability in Canada’s immigration and financial systems that appears far deeper than most Canadians have been told.

P.E.I.’s Provincial Nominee Program allows provinces to recommend immigrants for permanent residence based on local economic needs. It seems the program was exploited by wealthy applicants linked to Beijing to gain permanent residence in exchange for investments that often never materialized. It was all part of “money laundering, corruption, and elite capture at the highest levels.”

Hundreds of thousands of dollars came in crisp hundred-dollar bills on given weekends, amounting to millions over time. A monastery called Blessed Wisdom had set up a network of “corporations, land transfers, land flips, and citizens being paid under the table, cash for residences and property,” as was often done by organized crime.

Clement even called the Chinese government “the largest transnational organized crime group in the history of the world.” If true, the allegation raises an obvious question: how much of this activity has gone unnoticed or unchallenged by Canadian authorities, and why?

Dean Baxendale, CEO of the China Democracy Fund and Optimum Publishing International, published the book after five years of investigations.

“We followed the money, we followed the networks, and we followed the silence,” Baxendale said. “What we found were clear signs of elite capture, failed oversight and infiltration of Canadian institutions and political parties at the municipal, provincial and federal levels by actors aligned with the Chinese Communist Party’s United Front Work Department, the Ministry of State Security. In some cases, political donations have come from members of organized crime groups in our country and have certainly influenced political decision making over the years.”

For readers unfamiliar with them, the United Front Work Department is a Chinese Communist Party organization responsible for influence operations abroad, while the Ministry of State Security is China’s main civilian intelligence agency. Their involvement underscores the gravity of the allegations.

It is a troubling picture. Perhaps the reason Canada seems less and less like a democracy is that it has been compromised by foreign actors. And that same compromise appears to be hindering concrete actions in response.

One example Baxendale highlighted involved a PEI hotel. “We explore how a PEI hotel housed over 500 Chinese nationals, all allegedly trying to reclaim their $25,000 residency deposits, but who used a single hotel as their home address. The owner was charged by the CBSA, only to have the trial shut down by the federal government itself,” he said. The case became a key test of whether Canadian authorities were willing to pursue foreign interference through the courts.

The press conference came 476 days after Bill C-70 was passed to address foreign interference. The bill included the creation of Canada’s first foreign agent registry. Former MP Kevin Vuong rightly asked why the registry had not been authorized by cabinet. The delay raises doubts about Ottawa’s willingness to confront the problem directly.

“Why? What’s the reason for the delay?” Vuong asked.

Macdonald-Laurier Institute foreign policy director Christopher Coates called the revelations “beyond concerning” and warned, “The failures to adequately address our national security challenges threaten Canada’s relations with allies, impacting economic security and national prosperity.”

Former solicitor general of Canada and Prince Edward Island MP Wayne Easter called for a national inquiry into Beijing’s interference operations.

“There’s only one real way to get to the bottom of what is happening, and that would be a federal public inquiry,” Easter said. “We need a federal public inquiry that can subpoena witnesses, can trace bank accounts, can bring in people internationally, to get to the bottom of this issue.”

Baxendale called for “transparency, national scrutiny, and most of all for Canadians to wake up to the subtle siege under way.” This includes implementing a foreign influence transparency commissioner and a federal registry of beneficial owners.

If corruption runs as deeply as alleged, who will have the political will to properly respond? It will take more whistleblowers, changes in government and an insistent public to bring accountability. Without sustained pressure, the system that allowed these failures may also prevent their correction.

Lee Harding is a research fellow for the Frontier Centre for Public Policy.

Frontier Centre for Public Policy

Tent Cities Were Rare Five Years Ago. Now They’re Everywhere

From the Frontier Centre for Public Policy

Canada’s homelessness crisis has intensified dramatically, with about 60,000 people homeless this Christmas and chronic homelessness becoming entrenched as shelters overflow and encampments spread. Policy failures in immigration, housing, monetary policy, shelters, harm reduction, and Indigenous governance have driven the crisis. Only reversing these policies can meaningfully address it.

Encampments that were meant to be temporary have become a permanent feature in our communities

As Canadians settle in for the holiday season, 60,000 people across this country will spend Christmas night in a tent, a doorway, or a shelter bed intended to be temporary. Some will have been there for months, perhaps years. The number has quadrupled in six years.

In October 2024, enumerators in 74 Canadian communities conducted the most comprehensive count of homelessness this country has attempted. They found 17,088 people sleeping without shelter on a single autumn night, and 4,982 of them living in encampments. The count excluded Quebec entirely. The real number is certainly higher.

In Ontario alone, homelessness increased 51 per cent between 2016 and 2024. Chronic homelessness has tripled. For the first time, more than half of all homelessness in that province is chronic. People are no longer moving through the system. They are becoming permanent fixtures within it.

Toronto’s homeless population more than doubled between April 2021 and October 2024, from 7,300 to 15,418. Tents now appear in places that were never seen a decade ago. The city has 9,594 people using its shelter system on any given night, yet 158 are turned away each evening because no beds are available.

Calgary recorded 436 homeless deaths in 2023, nearly double the previous year. The Ontario report projects that without significant policy changes, between 165,000 and 294,000 people could experience homelessness annually in that province alone by 2035.

The federal government announced in September 2024 that it would allocate $250 million over two years to address encampments. Ontario received $88 million for ten municipalities. The Association of Municipalities of Ontario calculated that ending chronic homelessness in their province would require $11 billion over ten years. The federal contribution represents less than one per cent of what is needed.

Yet the same federal government found $50 billion for automotive subsidies and battery plants. They borrow tonnes of money to help foreign car manufacturers with EVs, while tens of thousands are homeless. But money alone does not solve problems. Pouring billions into a bureaucratic system that has failed spectacularly without addressing the policies that created the crisis would be useless.

Five years ago, tent cities were virtually unknown in most Canadian communities. Recent policy choices fuelled it, and different choices can help unmake it.

Start with immigration policy. The federal government increased annual targets to over 500,000 without ensuring housing capacity existed. Between 2021 and 2024, refugees and asylum seekers experiencing chronic homelessness increased by 475 per cent. These are people invited to Canada under federal policy, then abandoned to municipal shelter systems already at capacity.

Then there is monetary policy. Pandemic spending drove inflation, which made housing unaffordable. Housing supply remains constrained by policy. Development charges, zoning restrictions, and approval processes spanning years prevent construction at the required scale. Municipal governments layer fees onto new developments, making projects uneconomical.

Shelter policy itself has become counterproductive. The average shelter stay increased from 39 days in 2015 to 56 days in 2022. There are no time limits, no requirements, no expectations. Meanwhile, restrictive rules around curfews, visitors, and pets drive 85 per cent of homeless people to avoid shelters entirely, preferring tents to institutional control.

The expansion of harm reduction programs has substituted enabling for treatment. Safe supply initiatives provide drugs to addicts without requiring participation in recovery programs. Sixty-one per cent cite substance use issues, yet the policy response is to make drug use safer rather than to make sobriety achievable. Treatment programs with accountability would serve dignity far better than an endless supply of free drugs.

Indigenous people account for 44.6 per cent of those experiencing chronic homelessness in Northern Ontario despite comprising less than three per cent of the general population. This overrepresentation is exacerbated by policies that fail to recognize Indigenous governance and self-determination as essential. Billions allocated to Indigenous communities are never scrutinized.

The question Canadians might ask this winter is whether charity can substitute for competent policy. The answer is empirically clear: it cannot. What is required before any meaningful solutions is a reversal of the policies that broke it.

Marco Navarro-Genie is vice-president of research at the Frontier Centre for Public Policy and co-author with Barry Cooper of Canada’s COVID: The Story of a Pandemic Moral Panic (2023).

-

International2 days ago

International2 days agoTrump Says U.S. Strike Captured Nicolás Maduro and Wife Cilia Flores; Bondi Says Couple Possessed Machine Guns

-

Energy2 days ago

Energy2 days agoThe U.S. Just Removed a Dictator and Canada is Collateral Damage

-

Haultain Research2 days ago

Haultain Research2 days agoTrying to Defend Maduro’s Legitimacy

-

International2 days ago

International2 days agoUS Justice Department Accusing Maduro’s Inner Circle of a Narco-State Conspiracy

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoVacant Somali Daycares In Viral Videos Are Also Linked To $300 Million ‘Feeding Our Future’ Fraud

-

International2 days ago

International2 days agoU.S. Claims Western Hemispheric Domination, Denies Russia Security Interests On Its Own Border

-

Daily Caller1 day ago

Daily Caller1 day agoTrump Says US Going To Run Venezuela After Nabbing Maduro

-

Opinion1 day ago

Opinion1 day agoHell freezes over, CTV’s fabrication of fake news and our 2026 forecast is still searching for sunshine