Opinion

The cost of the Canada Winter Games?

The following Opinion piece comes from local writer/editorialist Garfield Marks.

The Gary W. Harris Canada Games Centre is a beautiful building but a very costly one. In more than money.

Construction costs of $22 million is an expensive undertaking. Operating and maintenance and interest on debt compounds the expense. The city is paying $11 million over a 10 year period or $1.15 million per year. (2017-2026) The college and the province are covering the rest, right?

Employees at Red Deer College are paying, too, and some are paying dearly. With their jobs. Red Deer College has to maintain a balanced budget, and with the huge cost of building, operating and maintaining this facility, they had to make cuts.

Early retirement, lay offs, and hours cut are an unintended consequence of the Canada Games. The Gary W. Harris Wellness Centre was only about 25% of the cost of the winter games and will cost some residents their paycheques, their livelihoods with no one available to top-up their incomes. Every resident will be paying for this centre for another 7 years, how much are we paying for the other 75%? Will we ever know?

The CFR cost the city last year $151,000 and $50,000 so far this year. Last fall when council voted themselves huge pay increases, one councillor stated they were worth the increases because they brought these events to the city.

Thank you for lightening our wallets and for some their jobs. Will we ever know the real costs of the Canada games, would we do it again if we knew the real costs? I don’t think so but I doubt we will ever know the real costs, will we?

Garfield Marks

Background Information:

Budget Requirements, Council Decision Points and Funding Sources: click reddeer.ca

“…Through a tri-party agreement with The City of Red Deer, the Canada Winter Games Host Society and Red Deer College, a contribution will be made to the College over a 10 year period totalling $11,501,000. This contribution represents about 50 per cent of the expected costs of the Olympic sized ice surface and squash courts to be housed within this facility. Payments of $1.15 million will be paid annually from 2017 to 2026 inclusive. The grants being given to RDC for this project are funded from debt and the Canada Winter Games grant...”

Crime

Inside the Fortified Sinaloa-Linked Compound Canada Still Can’t Seize After 12 Years of Legal War

Exclusive analysis shows how a fortified Surrey mansion tied in court filings to the Sinaloa Cartel’s leader has become the core of a stalled civil forfeiture fight, exposing Canada’s weak laws.

A British Columbia government lawsuit seeks to merge almost a decade of litigation into a single, high-stakes test of whether the province can finally seize a fortified mansion near the U.S. border that was first swept up in a 2014 fentanyl investigation, raided in 2016, and is now at the center of a new synthetic-opioid case alleging its occupants contracted with the leader of Mexico’s Sinaloa Cartel to flood narcotics into Canada.

In a notice of application filed in November 2025, the Director of Civil Forfeiture argues that all of the files revolve around one owner — James Sydney Sclater — and his flagship property on 77th Avenue, a multi-million-dollar house about twenty minutes’ drive from the Peace Arch crossing.

The property became newly notorious this spring when the latest effort to seize it pulled back the curtain on a 2024 RCMP raid. Officers say they entered a mansion ringed by compound fencing, steel gates and razor wire, wired with Chinese-made Hikvision surveillance cameras and hardened doors.

Inside, they reported finding hidden compartments in bedrooms and a basement bathroom packed with counterfeit pills and kilograms of raw synthetic opioids — including fentanyl — while assault-style rifles with screw-on suppressors, thousands of bullets and other firearms and body armour were stored in ways that suggested the residents were prepared for urban warfare. Investigators later alleged the targets had “connections to virtually every criminal gang in British Columbia.”

They also seized travel documents, including Mexican visas, before tracing the operation to alleged negotiations with Ismael “El Mayo” Zambada García, the reputed head of the Sinaloa Cartel, which Ottawa has now listed as a terrorist entity.

But for Canadian anti-mafia units, the address tracks the history of fentanyl’s deadly sweep across British Columbia, among the hardest-hit opioid death zones in North America. Their interest in the Surrey mansion stretches back to the first wave of lethal fentanyl trafficking that surged from Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside to Victoria and Vancouver Island around 2013 — making this single property a through-line in the North American opioid crisis, one that now runs through senior offices in Washington, Mexico City, Beijing and Ottawa.

Behind the hundreds of pages of civil filings reviewed by The Bureau lies a failure of governance as urgent as the unchecked advance of Latin cartels into Canadian cities — and as lethal as the synthetic opioids tied to the Surrey home.

British Columbia has been chasing the same house, and the same alleged transnational traffickers, through raids, affidavits and Charter of Rights battles since before fentanyl became a household word — and still has not managed to take the keys away.

The case documents explicitly point to a criminal-defence-friendly Supreme Court of Canada ruling — Stinchcombe, notoriously cited by police leaders — and to its role in undermining numerous major prosecutions involving networks tied to alleged narcoterror suspect Ryan Wedding and modern Canadian fentanyl-lab operators. One of those networks is the Wolfpack, a hybrid of Mexican cartels, Middle Eastern threat networks and biker gangs said to be supplied by Chinese Communist Party–linked criminal organizations and other Latin American cartel interests.

For the Director, the newest chapter begins in earnest with an RCMP raid on September 23, 2024. By then, investigators say, the Surrey mansion was no longer a domestic drug base, but the Canadian end of a supply line reaching into Sinaloa itself. Notably, 38 days later, on October 31, the RCMP announced a separate raid on what U.S. sources describe as the largest fentanyl lab ever discovered in the world, in rugged Falkland, B.C., roughly halfway between Vancouver and Calgary.

“The combined fentanyl and precursors seized at this facility could have amounted to over 95,500,000 potentially lethal doses of fentanyl, which have been prevented from entering our communities, or exported abroad,” the Mounties said.

But Sinaloa does not appear out of nowhere in the Surrey compound. The older case that the Director now wants consolidated onto the same track reaches back to a different phase of the crisis — and sketches an earlier incarnation of the Surrey house as a node in a Lower Mainland fentanyl network.

According to a 2019 notice of civil claim filed in the Victoria registry, the RCMP’s Project E-Probang began in November 2014, targeting a chemical narcotics distribution network that operated across the Lower Mainland and Vancouver Island. At the centre of that probe, police say, was Nicholas Lucier and his associates. The Director alleges that Sclater supplied Lucier’s network with controlled substances, while his father-in-law Gary Van Buuren lived with him at the 77th Avenue property and “assisted him in trafficking of controlled substances.”

The narrative that follows reads like a blueprint for mid-2010s fentanyl tradecraft. In October 2016, Lucier associate Yevgeniy Nagornyy-Kryvonos allegedly drove to the Surrey mansion to receive fentanyl from Sclater. Two days later, Nagornyy-Kryvonos met Daemon Gariepy; Gariepy was arrested shortly after that meeting, with one kilogram of fentanyl in his possession. On November 6, 2016, Sclater and Van Buuren visited the Surrey home of another associate, Azam Abdul. Van Buuren was picked up soon afterwards, allegedly carrying a kilogram of methamphetamine, a kilogram of fentanyl and two cellphones.

That same day, RCMP officers moved in on 16767 77th Avenue with a warrant. Inside, according to the pleadings, they found the kind of infrastructure that exists to supply major drug lines: long guns and improvised weapons scattered through the house, from conventional shotguns and rifles to a deactivated grenade, brass knuckles and a small armoury of knives, batons and throwing stars. There was a money counter parked near vacuum-sealing equipment; shelves of drug-packaging and currency-bundling materials; a body armour vest; and a banknote stash of roughly $20,000 in twenties, bundled with elastic bands and tucked into vacuum-sealed bags.

Fentanyl-containing pills and scoresheets documenting transactions sat alongside a multi-monitor surveillance system and a wiretap-detection kit. In a separate corner, tax records in Sclater’s name showed his declared income stepping down from more than $77,000 in 2010 to just over $11,000 by 2014 — data points that undermined his ability to carry mortgages on two Surrey properties.

The days that followed widened the picture.

A search at Abdul’s residence turned up scales, fentanyl and the tools of drug production and processing. Raids at Lucier’s home and two rentals he allegedly used produced what the Director describes as a haul worth a serious cartel’s attention: weapons and ammunition, more than $2-million in cash, and “thousands of grams” of fentanyl, cocaine, methamphetamine, a heroin-fentanyl mixture, fentanyl “oxy” tablets and MDMA, along with the scoresheets and processing gear that underpin a wholesale operation.

On Vancouver Island, an arrest search of Lucier allegedly produced tens of thousands of dollars in cash and multiple phones.

Lucier had been on Canadian police radar since at least the mid-2000s, and his story intertwines with the murder of B.C. cocaine broker Tom Gisby in Mexico — a killing that, according to a Canadian police source interviewed by The Bureau, formed part of a bloody consolidation of Mexican cartel power over Vancouver’s drug markets.

Lucier’s notoriety stretches back to October 2009, when Victoria police announced what they described as the city’s largest-ever cocaine bust. After a three-month undercover probe triggered by a shooting near Beacon Hill Park, nearly 100 officers carried out pre-dawn raids on five locations around the capital region, seizing roughly 22.5 kilograms of cocaine, four high-powered handguns, two vehicles and about $420,000 in cash. Lucier, then 41 and already on parole from a 2007 trafficking sentence involving multi-kilogram quantities of cocaine and heroin, was the lone suspect to slip away; a Canada-wide warrant was issued for his arrest.

In 2012, police in Mexico’s Nayarit state announced they had arrested Lucier in the Pacific resort city of Nuevo Vallarta on the outstanding Canadian warrant — the same town where Gisby, a longtime player in British Columbia’s cocaine trade, had been shot dead days earlier while ordering coffee at a Starbucks. Mexican authorities said Lucier had been living under an assumed name and socializing with other Canadian expatriates in the Puerto Vallarta area, including people who knew Gisby, although his arrest was not believed to be directly tied to the murder.

For investigators, the episode underscored how Canadian traffickers were deeply embedded in Mexican resort corridors from Mazatlán to Cancún that doubled as hubs for cartel-linked players from the north. In the years that followed, it would be former Canadian snowboarder Ryan Wedding — tightly associated with the Wolfpack networks tied to Western Canada’s fentanyl superlabs — who, according to U.S. government sources, rose above other Canadian narcos in those resort towns to become perhaps the single conduit for Latin American–supplied narcotics imported into Canada for both domestic consumption and onward transshipment.

The Bureau is a reader-supported publication.

To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

No Charges on Fentanyl Network

E-Probang era investigations underpin the 2019 civil claim that seeks forfeiture of both the 77th Avenue mansion and a second property at 15797 92nd Avenue. The Director’s position is that the homes were purchased and maintained with money that cannot be reconciled with Sclater’s reported earnings and should be treated as the proceeds of crime.

According to an amended notice of civil claim filed in May 2025, Sclater shared the 77th Avenue house with Hector Armando Chavez-Anchondo and John Brian Whalen, while Whalen’s father, John Edwin Whalen, and Brittany Anne Horvey are drawn into the case through their alleged roles in what the Director calls a drug trafficking organization, or DTO. The court filings describe not a loose circle of dealers, but a structured group that trafficked ketamine, methamphetamine, counterfeit Xanax, oxycodone, MDMA and fentanyl, and that “since June 2021 at the latest” had been working to import bulk cocaine from Mexico.

As the Director tells it, those efforts led straight to Sinaloa itself. The Surrey group is alleged to have agreed to purchase cocaine from senior cartel suppliers — operating at such scale, sophistication and power within Canada that they ultimately negotiated directly with alleged cartel boss Ismael “El Mayo” Zambada García.

When U.S. authorities arrested El Mayo on July 25, 2024, the Surrey operation is said to have lurched sideways, searching for “other parties” to keep the cocaine pipeline alive. In early September, Sclater, Chavez-Anchondo and Whalen Jr. allegedly pooled money to secure a shipment, then drove out to a rendezvous where they expected to collect their imported cocaine. According to the filings, their transport contact never materialized, and they returned to Surrey empty-handed.

Eleven days later, the RCMP arrived with a search warrant. Inside the mansion, officers reported walking into what looked more like a mid-level cartel outpost than a suburban home: firearms racked and stashed in multiple rooms, including assault-style rifles with screw-on suppressors and piles of ammunition, suggesting residents lived with the expectation of raids or perhaps clashes with some of the six other Mexican cartel networks aside from Sinaloa that have been identified in Canada by federal police.

Hidden compartments had been carved into bedrooms and a basement bathroom, where police say they found kilogram-scale quantities of ketamine and methamphetamine, counterfeit alprazolam tablets pressed to resemble Xanax, hundreds of oxycodone pills, a smaller but potent stash of fentanyl, and bundles of Canadian cash tucked away in a manner seasoned investigators instantly recognized — elastic-bound bricks, some vacuum-sealed, packed tightly enough to hint at far more money moving through the house than Sclater’s tax returns would ever show.

Downstairs, a kitchen freezer allegedly doubled as a storage vault for nearly a kilogram of MDMA; elsewhere, RCMP catalogued an Azure pleasure boat, a stable of trucks and custom motorcycles, gold jewellery and two Hikvision digital-video recorders that formed the core of a security system surveying the compound. The Director’s case is that neither Sclater nor his co-defendants had legitimate income capable of supporting that lifestyle, and that the house was both the proceeds and instrument of unlawful activity.

The timing was not incidental. Ottawa formally listed the Sinaloa Cartel as a terrorist entity on February 20, 2025, as one of seven Latin American criminal organizations added to Canada’s Criminal Code list in response to the fentanyl crisis and mounting U.S. pressure.

The Director’s pleadings lean into that backdrop, explicitly calling Sinaloa a terrorist entity and portraying 16767 77th Avenue as part of the infrastructure of a cartel now placed at the centre of a transnational security crisis.

While the alleged facts of police raids against the Surrey mansion seem to move steadily, the apparent lack of criminal charges against any of the targets — let alone a racketeering-style case against the network itself, which is effectively impossible to mount in Canada, where there is no U.S.-style RICO statute — reveals a litigation record that can fairly be described as broken and ineffectual, except from the perspective of criminal-defence lawyers and their clients.

The Director’s Victoria-based action was filed on May 22, 2019.

Sclater responded months later, disputing the forfeiture. In December 2019, the province produced its list of documents. Sclater replied in January 2020 with a list that named no documents at all. Over the next two years, Crown counsel sent a steady stream of letters — in March 2020, August 2021, and repeatedly between October 2021 and March 2022 — demanding a proper list and the financial and property records that would show how Sclater funded his holdings.

In a 2022 application, the Director’s frustration spilled onto the record. The submission notes that under the Civil Forfeiture Act, the core question is whether the Surrey properties are proceeds or instruments of unlawful activity — and that without basic financial disclosure, there is no way to test Sclater’s claim that they were acquired lawfully. The Director points out that documents showing income sources, mortgage servicing, and the acquisition and storage of weapons “are critical to a determination of the action on its merits,” and accuses Sclater of refusing or neglecting, for almost three years, to meet even the baseline disclosure duties imposed by the civil-procedure rules.

To head off what it casts as an attempt to turn the case into a criminal-style disclosure standoff, the Director leans on British Columbia v. PacNet Services Ltd., where the court rejected defence arguments that tried to graft the Supreme Court’s Stinchcombe-era criminal disclosure standards onto civil forfeiture proceedings. R. v. Stinchcombe — the 1991 Supreme Court of Canada decision that imposed a broad duty on the Crown to disclose all potentially relevant information so an accused can make full answer and defence under section 7 of the Charter — is firmly rooted in criminal procedure. Echoing that line of authority, the Director argues that there is “no justification” for Sclater to shelter behind Stinchcombe to avoid producing his own financial and property records, and tells the court it is “time to move [the case] forward,” with full document production or a lawful explanation for the default.

The Bureau is a reader-supported publication.

To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Constitutional Test

The newer Sinaloa-linked file adds another layer of complexity. Four of the five named defendants — Chavez-Anchondo, the two Whalens and Horvey — have not filed responses. In a separate notice of application, the Director now asks the court to treat the core allegations against them as admitted by default: that they were members of a drug trafficking organization; that they used or threatened violence; that they trafficked a catalogue of synthetic drugs and opioids; that they negotiated with Sinaloa; and that the weapons, cash and assets found in the 2024 raid are instruments and proceeds of crime.

For his part, Sclater is trying to turn the Surrey files into a constitutional test case. In his latest defence, he claims a lawful ownership interest in the 77th Avenue property, certain vehicles, cash, jewellery and electronic devices, and denies every allegation that he joined a criminal organization, conspired to import cocaine from Mexico, or negotiated with El Mayo. He acknowledges having a criminal record but disputes the particulars, and insists he had sufficient legitimate income to fund his properties and toys.

More ambitiously, he argues that the Civil Forfeiture Act itself is unconstitutional. By using allegations that he failed to declare taxable income as part of the proceeds-of-crime theory, he says, the province is encroaching on the federal government’s exclusive power over taxation under the Constitution Act, 1867. Assessing taxes owed, he points out, is the business of the Minister of National Revenue and the Tax Court of Canada. Civil forfeiture, in his view, cannot be used as a kind of shadow tax audit. He also asserts that the case “has arisen solely” from breaches of his Charter rights by RCMP officers and other state actors, arguing that the Director — “also an agent of the state” — is improperly relying on those breaches in seeking forfeiture.

It is, in effect, a bid to turn a forfeiture trial about a Surrey mansion into a referendum on how far provincial authorities can go in dismantling alleged drug networks without turning civil litigation into a criminal prosecution by another name.

All of this is unfolding against a national and continental backdrop that makes the Surrey house look less like an isolated problem than a symbol of a wider national failure.

Under National Fentanyl Sprint 2.0, Canadian police and partner agencies seized 386 kilograms of fentanyl and analogues between May 20 and October 31, 2025, with Ontario and British Columbia accounting for more than 90 per cent of that total. British Columbia reported 88 kilograms of seized fentanyl during the sprint. Yet those numbers miss some of the most alarming data points. Just days before the sprint window opened, Canada Border Services Agency officers at the Tsawwassen container facility in Delta intercepted more than 4,300 litres of chemicals from China, including 500 litres of propionyl chloride — a direct fentanyl precursor — and other substances capable of feeding clandestine labs in the Canadian wilderness for years. That shipment was destined for Calgary, and conservative estimates suggest it could have yielded enough fentanyl for billions of potentially lethal doses.

The Carney government continues to insist that Canada is primarily an end market, not a major exporter, and CBSA officials emphasize that only “small, personal doses” of finished fentanyl are being found heading south.

Seen from that angle, the fight over one Surrey mansion and the man who owns it becomes more than a story of Mexican cartels embedding in British Columbia’s wealthy suburbs.

It is a test of whether Canada’s patchwork of civil forfeiture laws, criminal prosecutions and Charter-driven disclosure rules can keep pace with transnational networks that blend Chinese chemical suppliers, Mexican cartels and domestic labs into a single system. For now, many Canadian police experts acknowledge in private — and some senior leaders flag in cautious public statements — that this test is being failed, and failed egregiously.

The Bureau is a reader-supported publication.

To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Health

The Data That Doesn’t Exist

ACIP voted to un-recommend the Hep B birth dose, but here’s the problem: they still can’t weigh the other side of the ledger

Sunday, something happened that has never happened in the history of American public health: ACIP voted 8-3 to un-recommend the universal birth dose of hepatitis B for babies born to mothers who test negative for the virus. After 34 years of jabbing every American newborn within hours of taking their first breath—regardless of whether their mother had hepatitis B—the committee finally acknowledged what 25 European countries figured out decades ago: it doesn’t make sense.

But watching this vote unfold, I couldn’t help but notice the absurdity of the debate itself. Committee members who opposed the change kept saying variations of the same thing: “We’ve heard ‘do no harm’ as a moral imperative. We are doing harm by changing this wording.” Another said “no rational science has been presented” to support the change.

How to End the Autism Epidemic is a reader-supported publication.

To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

And therein lies the fundamental problem with ACIP—and with the entire vaccine regulatory apparatus in America. They literally cannot weigh risk versus benefit because they only have data on one side of the scale.

The Missing Side of the Ledger

When ACIP debates adding or removing a vaccine from the schedule, they can produce endless data on disease incidence. They can show you charts demonstrating how hepatitis B cases in infants dropped from thousands to single digits after 1991. They can model projected infections if vaccination rates decline. They have this data at their fingertips because tracking infectious disease is something our public health apparatus actually does.

But ask them to produce equivalent data on vaccine injury, and you’ll get silence. Not “the data shows injuries are rare.” Not “here’s our comprehensive tracking of adverse events.” Just… nothing. A void where information should be.

This is not an accident. This is by design.

The safety trials for Engerix-B and Recombivax HB—the two hepatitis B vaccines given to American newborns—monitored adverse events for four to five days after injection. That’s it. If your baby developed seizures on day six, or regressed into autism over the following months, or developed autoimmune disease in the following year—none of that would appear in the pre-licensure safety data.

And the post-market surveillance? VAERS is a voluntary reporting system that the CDC itself acknowledges captures only a tiny fraction of adverse events. A Harvard-funded study found it captures perhaps 1% of actual vaccine injuries. Vaccine court has paid out over $5 billion in claims while simultaneously being structured to make filing nearly impossible for average families.

So when Dr. Cody Meissner voted against removing the Hep B birth dose and said he saw “clear evidence of the benefits” but “not the harms,” he was accidentally revealing the entire rotten structure. Of course he doesn’t see the harms. Nobody is systematically looking for them.

The Invisibility of Vaccine Injury

Here’s what most people don’t understand about vaccine injury: it’s nothing like a gunshot wound.

If you shoot someone, the cause is obvious. There’s a bullet, a wound, blood, a clear mechanism of action visible to any observer. Even a medical examiner who’s never seen the victim before can determine cause of death.

Vaccine injury doesn’t work that way. When aluminum nanoparticles from a vaccine cross the blood-brain barrier via macrophages, when they lodge in brain tissue and trigger chronic neuroinflammation, when a child slowly regresses over weeks or months—there’s no bullet. There’s no smoking gun. There’s just a before and an after, and a desperate parent trying to explain to doctors that something changed.

This invisibility is the vaccine program’s greatest protection. Because the injury mechanism is complex and delayed, because it doesn’t leave an obvious wound, because it requires actually looking to find—and because no one in authority is looking—the injuries simply don’t exist in the official record.

I watched my own son Jamie regress after his vaccines. A healthy, developing toddler who lost his words, stopped making eye contact, and retreated into a world we couldn’t reach. My wife and I know what happened. Thousands of other parents know the same thing happened to their children. But because this type of injury doesn’t show up on a simple blood test, because there’s no autopsy finding that says “vaccine-induced encephalopathy,” ACIP members can sit in a room and say with straight faces that they don’t see evidence of harm.

They’re not lying. They literally can’t see it. Because no one is measuring it.

The Chicken Pox Conundrum

Here’s an example that illustrates the insanity of our current approach.

The varicella (chicken pox) vaccine was added to the schedule in 1995. It definitely reduces chicken pox cases. The data is clear on that front. Mission accomplished, right?

But what about the other side of the ledger?

Emerging research suggests that wild chicken pox infection provides some protective effect against brain cancers—particularly glioma, the most common type of primary brain tumor. Multiple studies have found that people who had chicken pox as children have significantly lower rates of brain cancer later in life. The hypothesis is that the immune response to wild varicella provides lasting immunological benefits that extend far beyond preventing itchy spots.

Meanwhile, the vaccine itself has been associated with increased rates of autoimmune conditions. Studies have linked varicella vaccination to higher rates of herpes zoster (shingles) outbreaks in younger age groups, to autoimmune disorders, to various adverse events that weren’t captured in the original short-term safety trials.

So what’s the true risk-benefit of the chicken pox vaccine? Does preventing a week of itchy discomfort in childhood justify potentially increased rates of brain cancer and autoimmune disease later in life?

ACIP can’t answer this question. They literally don’t have the data. They can show you chicken pox cases going down. They cannot show you a comprehensive analysis of long-term neurological and immunological outcomes in vaccinated versus unvaccinated populations, because that study has never been done.

And so they keep recommending the vaccine based on the only data they have—the disease prevention data—while remaining willfully blind to consequences they’ve never bothered to measure.

The ACIP Paradox

Sunday’s vote was historic, but it also revealed the fundamental paradox of vaccine regulation in America.

The committee members who voted to remove the universal Hep B birth dose recommendation did so largely based on comparative evidence from Europe, parental concerns, and the basic logic that vaccinating a 12-hour-old baby for a sexually transmitted disease their mother doesn’t have makes no medical sense. They were right to do so.

But the committee members who voted against the change weren’t wrong either, from their perspective. They looked at the only data they have—disease prevention data—and concluded that removing the recommendation could lead to more hepatitis B cases. And within their limited framework, they’re correct.

The problem is the framework itself.

True risk-benefit analysis requires data on both risks AND benefits. ACIP has comprehensive data on benefits (disease prevention) and virtually no data on risks (vaccine injury). So every decision they make is fundamentally flawed from the start.

When Dr. Joseph Hibbeln complained that “no rational science has been presented” to support changing the recommendations, he was inadvertently indicting the entire system. Of course no comprehensive vaccine injury data was presented—such data doesn’t exist because no one has been willing to collect it.

This is like asking someone to make an informed financial decision while only showing them potential profits and hiding all possible losses. Of course the decision will be skewed. Of course you’ll end up with a bloated portfolio of high-risk investments that look great on paper.

The Real Reform

If RFK Jr. and the new HHS leadership want to actually fix the vaccine program, they need to understand that removing individual vaccines or making them “optional” is just rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic.

The real reform is creating the data infrastructure that should have existed from the beginning.

We need a comprehensive, long-term, vaccinated-versus-unvaccinated health outcomes study. Not a five-day safety trial. A multi-decade tracking of neurological, immunological, and developmental outcomes across populations with varying vaccination status. Florida just eliminated all vaccine mandates—that state alone could provide the data we need within ten years if someone had the courage to actually collect it.

We need a vaccine injury surveillance system that actually captures adverse events. Not a voluntary reporting system that misses 99% of injuries. An active surveillance system with trained clinicians looking for the kinds of delayed, complex injuries that vaccines actually cause.

We need accountability for manufacturers. The 1986 National Childhood Vaccine Injury Act removed all liability from vaccine makers—and predictably, the vaccine schedule exploded afterward while safety research stagnated. Why would any company invest in safety when they can’t be sued for injuries?

Without this data, every ACIP meeting will be the same performance we watched this week: members confidently citing disease prevention data while admitting they can’t see evidence of harm—not because harm doesn’t exist, but because no one is looking for it.

What Comes Next

Sunday’s vote was a crack in the wall. For the first time, an American regulatory body acknowledged that perhaps vaccinating every newborn within hours of birth for a disease primarily transmitted through sex and IV drug use doesn’t make sense when the mother has already tested negative.

But the forces of institutional inertia are already mobilizing. The American Academy of Pediatrics is “disappointed.” The American Medical Association is calling for the CDC to reject the recommendation. The pharmaceutical industry—which collects over $225 million annually from Hep B birth doses alone—will fight to restore the universal recommendation.

They will cite the same data they always cite: disease prevention data. Cases prevented. Infections avoided. Lives saved—theoretically.

They will not cite vaccine injury data, because that data doesn’t exist in any comprehensive form. They will not present long-term health outcomes in vaccinated versus unvaccinated children, because those studies have been actively avoided for decades. They will not acknowledge the thousands of families who have watched their children regress after vaccination, because those injuries aren’t captured in any official database.

And this is why ACIP will always be hamstrung. Until we build the data infrastructure to actually measure vaccine injury—to put real numbers on the other side of the ledger—every vaccine decision will be based on incomplete information. Every “risk-benefit analysis” will be a fraud, because we’re only measuring half the equation.

The hepatitis B birth dose vote was a small victory. But the larger battle—for actual science, for complete data, for true informed consent—that battle is just beginning.

And until we win it, ACIP will continue making decisions in the dark, confidently citing evidence of benefits while remaining deliberately blind to the harms they’ve never bothered to measure.

About the author

J.B. Handley is the proud father of a child with Autism. He spent his career in the private equity industry and received his undergraduate degree with honors from Stanford University. His first book, How to End the Autism Epidemic, was published in September 2018. The book has sold more than 75,000 copies, was an NPD Bookscan and Publisher’s Weekly Bestseller, broke the Top 40 on Amazon, and has more than 1,000 Five-star reviews. Mr. Handley and his nonspeaking son are also the authors of Underestimated: An Autism Miracle and co-produced the film SPELLERS, available now on YouTube.

How to End the Autism Epidemic is a reader-supported publication.

To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoCarney government should privatize airports—then open airline industry to competition

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoWhat’s Going On With Global Affairs Canada and Their $392 Million Spending Trip to Brazil?

-

Energy2 days ago

Energy2 days agoCanada following Europe’s stumble by ignoring energy reality

-

Bruce Dowbiggin15 hours ago

Bruce Dowbiggin15 hours agoIntegration Or Indignation: Whose Strategy Worked Best Against Trump?

-

COVID-1916 hours ago

COVID-1916 hours agoUniversity of Colorado will pay $10 million to staff, students for trying to force them to take COVID shots

-

Banks2 days ago

Banks2 days agoTo increase competition in Canadian banking, mandate and mindset of bank regulators must change

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoLoblaws Owes Canadians Up to $500 Million in “Secret” Bread Cash

-

Focal Points1 day ago

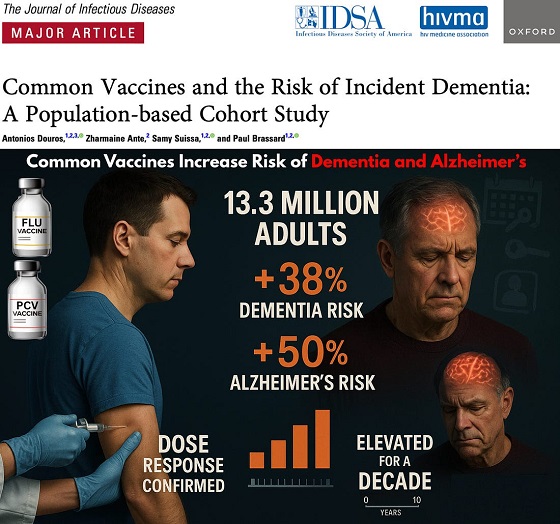

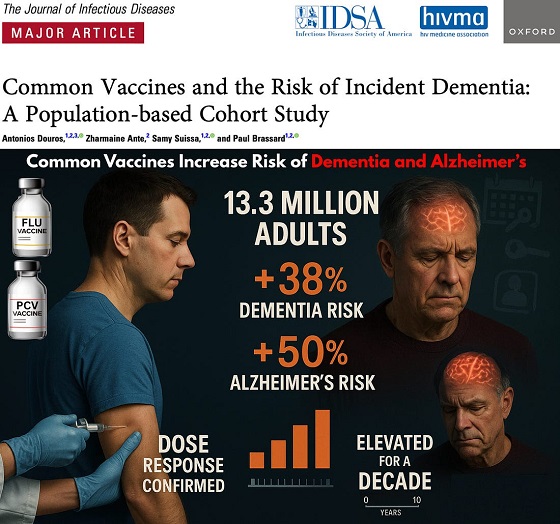

Focal Points1 day agoCommon Vaccines Linked to 38-50% Increased Risk of Dementia and Alzheimer’s