Addictions

New organizations for mental health and addictions to provide focused care and take pressure off health system

Refocusing health care: mental health and addiction

Alberta’s government is creating two new organizations that will support the development of the mental health and addiction system of care.

In November 2023, Alberta’s government announced it would be refocusing health care with the creation of four new organizations that will be responsible for the oversight and delivery of health care services in the province. The four new organizations include acute care, continuing care, primary care and mental health and addiction. The mental health and addiction organization will be the first of these to be established when it becomes an entity later this year.

The new mental health and addiction organization, Recovery Alberta, will be responsible for the delivery of mental health and addiction services currently delivered by Alberta Health Services (AHS). In addition, Alberta’s government is establishing the Canadian Centre of Recovery Excellence (CoRE) to support Alberta’s government in building recovery-oriented systems of care by researching best practices for recovery from around the world, analyzing data and making evidence-based recommendations.

“Refocusing health care enables us to better prioritize the health care and services Albertans need. Giving Albertans living with mental health or addiction challenges an opportunity to pursue recovery and live a contributing life is the responsible and compassionate thing to do. I am so proud of the work we have done to be leaders on recovery, and I am looking forward to seeing both Recovery Alberta and the Canadian Centre of Recovery Excellence continue this work for years to come.”

“Alberta is leading the country with the development of the Alberta Recovery Model to address mental health and addiction challenges. The establishment of these two new organizations will support the delivery of recovery-oriented services to Albertans and will further cement Alberta as a leader in the field. We are proud to establish Recovery Alberta and CoRE as part of the Alberta Recovery Model.”

“We’re making good progress on refocusing health care in Alberta. Today marks a pivotal milestone towards creating a system that truly serves the needs of Albertans. Through this refocused approach, our aim is to prioritize the needs of individuals and families to find a primary care provider, get urgent care without long waits, access the best continuing care options, and have robust support systems for addiction recovery and mental health treatment.”

Recovery Alberta

In August 2023, Alberta’s Ministry of Mental Health and Addiction began the process of consolidating the delivery of mental health and addiction services within AHS, a process that was completed in November 2023 with no disruption to services.

Recovery Alberta will report to the Ministry of Mental Health and Addiction and further support the Ministry’s mandate to provide high-quality, recovery-oriented mental health and addiction services to Albertans. It is anticipated Recovery Alberta will be fully operational by summer 2024 and will operate with an annual budget of $1.13 billion from Alberta’s government. This funding currently supports the delivery of mental health and addiction services through AHS.

The current provincial leadership team for Addiction and Mental Health and Correctional Health Services within AHS will form the leadership team of Recovery Alberta. When Recovery Alberta is fully established, Kerry Bales, the current Chief Program Officer for Addiction and Mental Health and Correctional Health Services within AHS will be appointed as CEO. Dr. Nick Mitchell, Provincial Medical Director, Addiction and Mental Health and Correctional Health Services within AHS, will become the Provincial Medical Director for Recovery Alberta.

“Recovery Alberta will build on the strong foundation of existing mental health and addiction services that staff and clinicians deliver. By working closely with Alberta Mental Health and Addiction and the Canadian Centre of Recovery Excellence, Recovery Alberta will continue to set a high standard of care for mental health and addiction recovery across the province, and beyond.”

“Albertans deserve patient-centered care when and where they need it. By establishing Recovery Alberta, we have an opportunity to work together in a new way to make that a reality for our patients and our communities.”

While timelines are dependent on legislative amendments yet to be introduced, the Ministry of Mental Health and Addiction is aiming to establish the corporate structure of Recovery Alberta by June 3. Following the establishment of the corporate structure and executive team, staff and services would begin operation under the banner of Recovery Alberta on July 1.

Frontline workers and service providers will continue to be essential to care for Albertans. To ensure stability of services to Albertans, there will be no changes to terms and conditions of employment for AHS addiction and mental health staff transitioning to Recovery Alberta. Additionally, there will be no changes to grants or contracts for service providers currently under agreement with AHS upon establishment of Recovery Alberta.

Canadian Centre of Recovery Excellence (CoRE)

Alberta’s government has been leading the country in creating a system focused on recovery by building on evidence-based best practices from around the world. In five years, Alberta has removed user fees for treatment, increased publicly funded treatment capacity by 55 per cent and built two recovery communities with nine more on the way. Alberta’s government has also pioneered new best practices such as making evidence-based treatment medication available same day with no cost and no waitlist across the province through the Virtual Opioid Dependency Program.

To continue the innovative work required to improve the mental health and addiction system, Alberta’s government is creating the Canadian Centre of Recovery Excellence to inform best practices in mental health and addiction, conduct research and program evaluation and support the development of evidence-based policies for mental health and addiction. CoRE will be established as a crown corporation through legislation to be introduced this spring.

Alberta’s government has committed $5 million through Budget 2024 to support the establishment of CoRE. It is anticipated CoRE will be operational by this summer.

The CoRE leadership team will consist of Kym Kaufmann, former Deputy Minister of Mental Health and Community Wellness in Manitoba as the CEO. She will be supported by Dr. Nathaniel Day as Chief Scientific Officer of CoRE. Dr. Day currently serves as the Medical Director of Addiction and Mental Health within AHS.

“There is a need for more scientific evidence on how best to help those impacted by addiction within our society. The Canadian Centre of Recovery Excellence will generate new and expanded evidence on the most effective means to support individuals to start and sustain recovery.”

“The Canadian Centre of Recovery Excellence will provide the research and data we need to understand what works best when it comes to recovery. This new expertise and expanded evidence will provide us with further insight into how we can support communities, service providers and frontline staff to effectively help those living with addiction and mental health challenges.”

Quick facts

- Budget 2024 will invest more than $1.55 billion to continue building the Alberta Recovery Model.

- This includes a $1.13 billion transfer from Health to Mental Health and Addiction (MHA) for mental health and addiction services currently delivered by Alberta Health Services.

- Virtual engagement sessions for AHS staff and service providers will be held on April 11, 16, 17 and 22.

Related information

Addictions

From opioids to office: An interview with Alberta’s new addiction minister

By Alexandra Keeler

Rick Wilson shares what led him into — and out of — addiction, his goals for Alberta’s recovery model and the value of an ‘Indigenous lens’

In mid-May, Alberta appointed Rick Wilson as the province’s new minister of mental health and addiction.

Wilson, who represents the Maskwacîs-Wetaskiwin riding south of Edmonton, was Alberta’s longest serving minister of Indigenous relations, serving from 2019 to this year.

Now, Wilson is tasked with accelerating the implementation of the Alberta Model, a recovery-oriented system of care that prioritizes addiction prevention, early intervention and treatment over harm reduction.

Canadian Affairs spoke with Wilson about his priorities in the new role, how his prior work with Indigenous communities shapes his perspective and what lies ahead for mental health and addiction care in Alberta.

AK: I understand you’ve been tasked with advancing the Alberta Recovery Model. What aspects of the model require the most focus in the term ahead?

RW: My goal is going to be to keep the momentum going. [We need to] get all the recovery communities opened up, keep expanding our supports, like CASA Classrooms [classroom-based mental health programs], and just keep filling the gaps for better information.

AK: Why was your predecessor, Dan Williams, shuffled out of the post?

It was a cascading event. Our speaker took a job in Washington, so we voted for a new speaker, Rick McIver. That left a hole in Municipal Affairs, [where Dan was moved]. I’d been bugging Premier Smith for more help with addictions and mental health. She said, ‘Go fix it then, I’ll put you there.’

AK: Do you have personal experience with mental health or addiction struggles?

RW: Do you want the whole sad story here?

I used to raise a lot of cattle and had one really rank bull that was terrorizing the farm. One morning I tried to get him up, and it didn’t end well — he got me down, fractured several vertebrae in my neck and back, and collapsed my lungs. I don’t know how I survived, but somehow I did.

For a year, I couldn’t walk. I was in so much pain I didn’t even know who I was. I would literally pray for one second of relief. Whatever the doctor gives you, you’ll take it — Oxytocin to Percocet; you name it, I was on it. My wife said she’d give me a pill and an hour later, I’d be begging her for more. This went on for close to a year.

I finally had what’s called laser spinal surgery. I was one of the very lucky ones. I went into it in a wheelchair, but I came out walking, and the pain was gone.

About a week later, I told my wife, ‘I think I’m full of infection — I’m burning up with fever, I’m sweating, and I think they’ve nicked a nerve. I feel like I got a giant hole in me.’ She looked at me like I was crazy.

We went to the doctor. He said I was completely healed and asked, ‘What do they have you on?’ Then he said, ‘You just quit taking everything?’ I told him, ‘Yeah, there’s no more pain, so I just quit.’

He said, ‘Well, you’re in withdrawal.’

Once I knew what it was, I was able to tough it out, but it’s not a pleasant experience. I don’t think people are really trying to get high — you just don’t want to feel that alone. I literally felt like there was a hole right through me, like I was just empty inside. So I have a lot of empathy for people that are in addiction.

Rick Wilson was sworn in as the Minister of Mental Health and Addictions on May 16. | Rick Wilson via Facebook

RW: When I was in Indigenous Relations, half my time was spent around addiction issues. It’s horrible. Out on the First Nations, there’s hardly a chief who hasn’t lost a son or somebody close to them. That’s all I did — go to funerals, one after another.

What I learned was you really just have to listen — and that’s one thing the government isn’t good at.

AK: What learnings from that role are you bringing to your new portfolio, and how do you see them benefiting your work in mental health and addiction?

RW: I want to put an Indigenous lens on the whole thing. I think that’s the piece we’re missing. What I found most successful was to use their culture. Get the elders involved. They have the sweats, smudges and language. To take somebody’s language away is devastating.

You hear a lot about reconciliation, but I took it for real. My good friend Willie Littlechild said, ‘Minister, I want to see some reconcili-action.’ He said I could use that — so I do, a lot.

AK: Can Indigenous recovery models work more broadly for non-Indigenous Albertans?

RW: I’ve really seen it work with non-Indigenous folks as well. But everybody’s going to be different. For some people, maybe Christianity is the way to go. And for some people, it’s Alcoholics Anonymous.

I think [the common thread] is that hope. [When you’re addicted] you feel hopeless.

I felt empty, and you need something to replace that emptiness. The problem is, you turn to alcohol, you turn to drugs to fill that gap, and that’s not going to do it. It’s a very temporary fix that just pushes you deeper down the rabbit hole.

Minister Rick Wilson celebrates the Pigeon Lake Regional School Class of 2025 on May 25. | Rick Wilson via Facebook

AK: Can you explain what a recovery community is, and how it fits into the province’s continuum of care?

RW: The way they used to do it, you’d throw someone in recovery for a couple of weeks [and expect] that should cure it, then out you go. Well, that doesn’t work.

[Now] it’s more of a holistic approach: you go into detox, and then from there, you go into rehab. Some people fall out of rehab, [but they go] back into detox, and eventually you start working your way around the circle.

Transitional housing is key. You can’t just send someone back into the community without support — they’ll relapse. After housing, the focus is on community reintegration, finding work, and family support. It’s like an Indigenous healing circle — a full circle to prevent falling back into addiction.

We’re working on 11 sites — one in Red Deer, Gunn, Lethbridge and Calgary opening this summer. Seven more are planned, including Edmonton, Grande Prairie and five with Indigenous communities.

AK: Some critics argue that the Alberta Model leans toward coercive care, and that the benefits of involuntary treatment may not outweigh the risks and costs. How will the Compassionate Intervention Act, which mandates addiction treatment, address those concerns?

RW: Compassionate care isn’t just for the individuals [with substance use disorders]. We have to be compassionate for them, but we also have to be compassionate for the people in their community that are impacted.

In my own riding in the Maskwacîs-Wetaskiwin — some people come in [to the hospital] three times in a day that have overdosed. To overdose several times a day — you’re doing brain damage when you’re at that point.

These people are in dire straits, and we have to intervene with them, because they’re not even capable of thinking for themselves [or] to go for voluntary treatment. We want to give the people that are addicted that opportunity to rebuild their lives. Right now, there’s just a lot of enabling going on.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

This article was produced through the Breaking Needles Fellowship Program, which provided a grant to Canadian Affairs, a digital media outlet, to fund journalism exploring addiction and crime in Canada. Articles produced through the Fellowship are co-published by Break The Needle and Canadian Affairs.

Addictions

After eight years, Canada still lacks long-term data on safer supply

By Alexandra Keeler

Canada has spent more than $100 million on safer supply programs, but has failed to research their long-term effects

Canada lacks long-term data on safer supply programs, despite funding these programs for years.

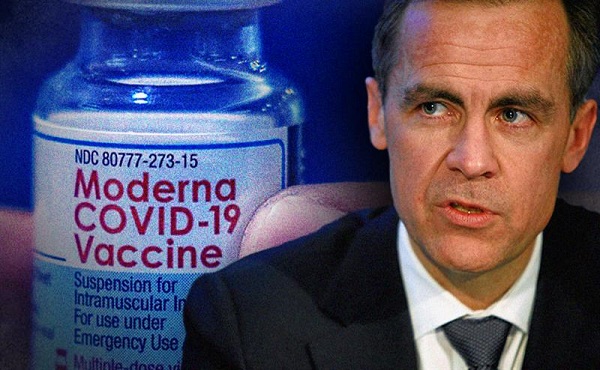

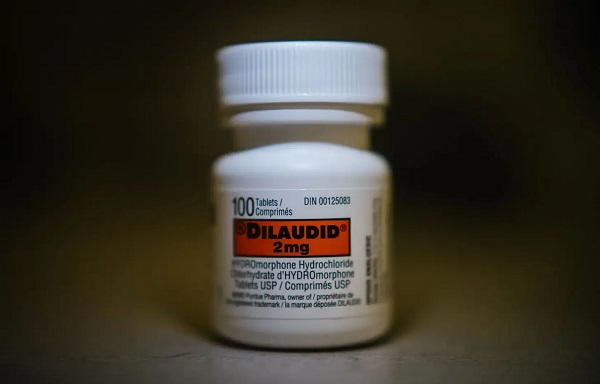

Safer supply programs dispense pharmaceutical opioids as a replacement for toxic street drugs.

There is a growing body of research on safer supply’s short-term health effects. But there are no Canadian studies that evaluate program participants’ health impacts beyond 18 months.

The absence of research into long-term data on safer supply means policymakers do not understand how safer supply affects participants’ health, substance use or social outcomes over time.

“Long-term data is important because it helps us understand not just short-term health outcomes like reduced overdoses, but also broader impacts on quality of life, stability and health care use,” said Farihah Ali, scientific lead at the Institute for Mental Health Policy Research at CAMH. The Centre for Addiction and Mental Health is one of Canada’s leading centres for addiction research and clinical care.

Pilot projects

Canada’s first safer supply programs were introduced in Ontario in 2016. Those programs were initially small in scope, intended for a small group of high-risk individuals.

In 2020, the federal government began funding safer supply pilot programs across the country. Provinces are responsible for the delivery and regulation of these programs.

B.C. introduced provincewide programs in 2021. Other provinces, such as Alberta, have restricted safer supply access to a very small number of clinics, and have generally shifted away from harm reduction models in favour of recovery-oriented approaches.

According to the Canadian Public Health Association, an advocacy organization, the original goal for safer supply was to reduce deaths and harms associated with the unregulated toxic drug supply. It was not meant to replace addiction treatment, but to rather act as a bridge to further care.

However, a 2023 report by researchers at McMaster University and Simon Fraser University noted safer supply “does not principally operate toward goals of treatment or recovery.” The report describes safer supply instead as an emergency intervention focused on stabilization and survival.

Evidence gaps

There is a small but growing body of short-term studies on the health effects of Canada’s safer supply programs. Most only track participants’ outcomes for up to 12 months.

Some of those studies suggest safer supply may reduce the immediate harms associated with drug use.

A 2024 study found a 91 per cent reduction in the risk of death among high-risk individuals receiving safer supply in B.C. Critics have raised concerns about the study’s methodology, sample size and confounding variables.

In contrast, a March study suggested B.C.’s safer supply and decriminalization policies may be associated with increased hospitalizations. These findings also sparked controversy, with experts debating how well the data isolate causal impacts.

And a comparative study released in April also showed some positive outcomes from safer supply. It too sparked significant expert debate.

‘Arms-length’

Of all the provinces, B.C. has implemented safer supply most broadly. The province’s health ministry did not directly respond when asked about the long-term goals of its safer supply program, or whether B.C. collects longitudinal data on program participants’ health outcomes.

“Evidence shows [safer supply] helps separate people from the unregulated drug supply, manage their substance use and withdrawal symptoms with regulated medications, and helps connect them to voluntary health and social supports,” a Ministry of Health spokesperson told Canadian Affairs in an email.

The ministry did not provide the evidence it referenced.

At the federal level, Health Canada confirmed that, to date, it has funded just two evaluations of safer supply programs, despite spending more than $100 million on safer supply since April 2023.

The first was a short-term study, funded by the federal government’s Substance Use and Addictions Program program. Conducted over four months, that study assessed 10 safer supply programs in Ontario, B.C., and New Brunswick. It documented initial impacts on participants’ lives and program delivery, primarily through qualitative methods such as interviews and surveys.

The second study is an ongoing, “arms-length evaluation” of 11 safer supply pilot programs funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), Canada’s federal health research agency.

When asked about long-term research on safer supply, Health Canada referred Canadian Affairs to a 2022 funding announcement about this multi-year evaluation. While the evaluation is being conducted over several years, it is unclear if it includes long-term tracking of patients’ outcomes.

Barriers and resistance

There are a number of factors that make it challenging to evaluate safer supply programs over long periods.

Ali, of CAMH, says unstable, short-term funding can disrupt long-term research.

“When programs are shut down or scaled back, we lose contact with participants and the ability to track outcomes over time,” she said.

Program participants can also be difficult to track over long periods, she says. Many struggle with housing insecurity, health instability and criminalization.

Frontline staff also face burnout and high turnover, she says, limiting support for such research activities.

Additionally, there are tradeoffs between the anonymity needed to encourage patients to access safer supply programs and the ability to collect detailed data.

“Ethical concerns — like not wanting to burden participants or risk their safety or confidentiality — require us to design studies that are trauma-informed and flexible, which adds complexity to long-term data collection,” Ali said.

Julian Somers, a clinical psychologist and professor at Simon Fraser University, says B.C.’s failure to conduct long-term evaluations of its safer supply programs is not just an oversight, but an act of negligence.

“B.C. has some of the best pharmaceutical data systems in the world,” Somers said, referring to PharmaCare and PharmaNet — databases that capture every prescription drug transaction in the province.

Somers says his team previously used PharmaNet data to examine prescribed opioids’ effects on health and social outcomes. In 2017, he proposed a long-term safer supply evaluation using these tools.

In 2017, he proposed a long-term evaluation of B.C.’s safer supply programs.

The province declined.

According to Ali, “Future research should explore how safer supply impacts people’s long-term health, stability and connection to care.”

“We also need to listen to people’s experiences, how safer supply affects their daily lives, their sense of dignity, and their relationships with care providers through qualitative mechanisms.”

This article was produced through the Breaking Needles Fellowship Program, which provided a grant to Canadian Affairs, a digital media outlet, to fund journalism exploring addiction and crime in Canada. Articles produced through the Fellowship are co-published by Break The Needle and Canadian Affairs.

-

Education1 day ago

Education1 day agoWhy more parents are turning to Christian schools

-

Alberta1 day ago

Alberta1 day agoUpgrades at Port of Churchill spark ambitions for nation-building Arctic exports

-

Alberta1 day ago

Alberta1 day agoOPEC+ is playing a dangerous game with oil

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoIs dirty Chinese money undermining Canada’s Arctic?

-

COVID-191 day ago

COVID-191 day agoJapan disposes $1.6 billion worth of COVID drugs nobody used

-

conflict1 day ago

conflict1 day agoOne of the world’s oldest Christian Communities is dying in Syria. Will the West stay silent?

-

COVID-191 day ago

COVID-191 day agoWATCH: Big Pharma scientist admits COVID shot not ‘safe and effective’ to O’Keefe journalist

-

Bruce Dowbiggin1 day ago

Bruce Dowbiggin1 day agoHow Did PEI Become A Forward Branch Plant For Xi’s China?