Christopher Rufo

Luigi Mangione and Left-Wing Nihilism

The assassination of the UnitedHealthcare CEO represents a dark turn in our politics.

The following transcript of the episode has been lightly edited for clarity:

The most significant story in this week’s news cycle was, without a doubt, the spectacular assassination of the UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson and the subsequent capture of his alleged assassin: a young, handsome, well-educated person named Luigi Mangione, who authorities say was in possession of a weapon and a manifesto outlining a possible motive for the crime. The assassination itself, which unfolded last week, was engineered for maximum spectacle, and in fact, it was captured on a CCTV camera, and these images rocketed across the country and across the world. This was a spectacular assassination because the target was the CEO of a major corporation. The execution was brazen. The assassin, who wore a mask and a hood, patiently approached the CEO as he was exiting a hotel on the streets of Manhattan—and then, at close range, with cold calculation, pulled the trigger multiple times until he was dead. On the scene, police found shells of the bullets etched with phrases like “deny, defend, depose,” indicating a deliberate preparation—this was a cold-blooded killing—as well as an ideological motivation. There was resentment, anger, and hatred because of UnitedHealthcare and, supposedly, because of its policies.

This week, there was another layer added to this story that made it even more of a media-feeding frenzy. The suspect and alleged assassin was revealed as a young man named Luigi Mangione, who had all the outward trappings of success. This was an individual who comes from a very wealthy family in the Baltimore area. He’s handsome by appearance, physically fit, he appears to be highly intelligent from the trail of social media posts that he left, and he had two degrees, which he earned in quick succession from the University of Pennsylvania—part of the Ivy League. You had these two seemingly incongruous images or stories suddenly collapsing into one another, and it led to this great question: Why? Why would someone who in theory has everything in life—looking ahead in his life everything is looking up—and yet he succumbed to this very dark assassination? He orchestrated it carefully, he attempted to escape, and then he was caught in a very marginal position, huddled in a McDonald’s in the middle of nowhere, Pennsylvania.

It’s important to take this seriously at two levels. The first level, of course, is trying to trace the ideological progression of Luigi Mangione from the details that we’ve discovered in the media to try to understand both his stated rationale, but then also, perhaps, the underlying psychological motivation behind this crime. Secondarily, it’s important to see this crime, which has set off a media feeding frenzy—you have look-alike contests, you have people idealizing and even idolizing this individual, you have even popular politicians such as Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Bernie Sanders, and Elizabeth Warren trying to harvest some of this energy that has been unleashed by this revenge killing into their political program, their left-wing economic program—while, of course, carefully creating some deniability, some distance, between themselves and the actual crime of murder.

First, let’s look at the question of motive. Motive is a key element in any criminal investigation, but in a political crime, which this by all accounts appears to be, it’s even more important. Mangione was like many of us who have an elite education, who grew up at least part of our lives on the Internet—we leave a trail of posts, of engagement, of comments, of interactions as part of our digital life, and he was no exception. He left a trail of clues, a trail of statements, a trail of bits of information on the social media platform X, on the publication platform Substack, and on the reader-sharing application Goodreads. Is this a total revelation of all of his thoughts, feelings, motivations, and problems? No. But it does give us some information to start piecing together.

What strikes me is that his ideological development—you can look at it over the last years by tracing his readings, his statements, his interests—and a few years ago—and the left-wing press has really focused on this as the source of his ideological transgressions or resentments—it started with what I could think of as elite centrist ideologies. He was sharing content from Yuval Noah Harari, who is the World Economic Forum guru who thinks that human beings are rats that have to be guided through the maze of the modern world, and that we can someday overcome our own nature. He was sharing content from the social psychologist Jonathan Haidt, who has captured in a substantive way some of the professional class anxieties about technology, youth behavior, and with other colleagues around natalism and birth rates, which were also a focus of Mangione’s a couple of years ago. Then third, you have him sharing content and discussing content from the Stanford scientist and health guru Andrew Huberman. I think of him as the cold tank protocol—all of these small lifestyle adjustments and healthcare protocols and supplement routines that, in theory, take the human being to another level of performance. Again, reducing human nature to its biological nature—you can make incremental improvements, you could take these supplements, you could sit in an ice bath for an hour, and you’ll be 12% more effective. These are banal elite ideologies. That’s not to say that there’s no truth to all of them. There are certainly some insights that are worth garnering. But what all these have in common is a popularity and a safety in elite circles. You can follow Harari, you can follow Haidt, you can follow Huberman—you’re signaling, perhaps, some dissidence from the establishment, the left-liberal establishment—but you’re well within the confines of elite ideologies that are reducible, and this is important, to a scientific and quantifiable base. This is almost a McKinsey-style ideology, which ties in very much to the world of elite Ivy Leagues.

But beginning perhaps two years ago, certainly a year ago, and accelerating in recent months, you saw a change in his consumption, a change in his discussion. He moved from banal elite ideologies to what I think of as banal radical ideologies. He wrote a review of the Unabomber’s manifesto that was quite positive. I think he gave it four stars on Goodreads, and he felt sympathy with some of the more radical ideas—some of the rationalizations for violence that were in Ted Kaczynski’s manifesto. He also bought into a left-wing corporate greed narrative. This is a standard narrative over the past 100 years in American life that is mobilized on the left, especially in times of economic uncertainty, that has the populist component. It explains misery, misfortune, and ill health because of corporate greed, corporate corruption, and corporate malfeasance. It provides a great target upon which to project one’s own miseries.

He was also talking about new age, radical ideologies in the form of psychedelics. If you’ve been around tech centrists in Silicon Valley, New York, or Seattle, there’s a subculture that has adopted psychedelics, not a countercultural phenomenon like it might have been in the late 1960s, but as a way to unlock creativity, insight, productivity—the Steve Jobs typification of psychedelics that are not only deemed acceptable in these professional environments but deemed a substitute for a grounded religious life. You can go to a shaman in South America, slurp a cup of Ayahuasca, and unlock your brain, which can then be used to demystify the world. You can find your authentic self, and then you can exit the trappings or the drudgeries of the modern capitalist society.

You’re watching this arc of transformation, and simultaneously, some of the personal tidbits start to stack up. This is an individual who went through what appears to be a very painful back surgery. There were published reports saying that he may have lost his job at a tech firm where he was working as an engineer. And then he was living, at least for a time, in a commune environment in Hawaii—the kind of new age, professional class, affluent communities. These are features of some places around the world. You have them in some boroughs of New York, you have them in places like Berkeley, California, and places like some of the more secluded places in Hawaii. There is the potential, although it’s not totally confirmed, that this narrative of personal struggle, personal pain, personal unhappiness because of his medical condition—in the context of someone who was very healthy, very strong, very physically fit, he was an athlete, at least high school—could have led him to snap. We have the personal progression layered onto the ideological progression, but whatever combination of these happened, what’s certain is that he did snap—because someone who is well can see the folly in murdering someone on the streets in cold blood. Someone who is unwell can rationalize that action, which is exactly what he did.

But we have another, more important layer that we can peel back in two places. When the police caught him in Altoona, Pennsylvania, he had an alleged manifesto—a few hundred words—and a spiral-bound notebook with specific notes that are alleged to be part of the planning of this crime. This is where it becomes very interesting, because the more specific that we get about the actual crime, the more it dovetails and mimics the narrative structure of radical left-wing ideologies, and, as I’ll argue, radical left-wing nihilism.

At the beginning of the supposedly handwritten manifesto, he says some boilerplate leftist lines—that we have the most expensive healthcare in the world and yet the 42nd longest life expectancy. In other words, we’re not getting the value that we’re putting into it. And the critical question is then: Why? And he has an answer. He denounces “the corruption and greed in the industry. He denounces their quest for “profit” and in the other notebook, he said he wanted to murder the CEO of the largest health insurance company at the annual, parasitic, bean-counter convention. We can break down each of those words. “Parasitic” is a left-wing trope: capitalist parasites extracting the labor of the working class—or in this case, insurance company parasites extracting from the pain of struggling Americans. Then he calls it a bean-counter convention. The CEO was trained as an accountant. The insult here is that you can’t put a price on health, on human beings, on goodness—but that’s exactly what these capitalist parasites do, and therefore, they deserve to be eliminated because they don’t have an appreciation for life. They merely monetize it and convert it into death.

What’s interesting about this manifesto is two things. One is that for a very smart person, he’s reduced it to very simplistic, left-wing narratives, and it was only a few hundred words. He didn’t even actually think through why he was committing the crime in detail. In fact, he says at one point, “I do not pretend to be the most qualified person to lay out the full argument about the corruption of America’s healthcare system”—and yet he felt he was educated enough to plot and execute a plan to murder this company’s CEO.

Beneath this admittedly surface-level, left-wing rhetoric, what is really happening here? It’s something that I have witnessed over the last few years and documented in various capacities, but it really comes into sharp focus here. It’s a form of left-wing nihilism.

Typically, the left likes to present itself as left-wing progressivism. “We’re going to make the world better. We’re going to provide more healthcare. We’re going to get a public option. We’re going to have the Affordable Care Act. We’re going to have a single-payer system that will provide care and value each human being.” That’s the narrative in a traditional left-wing progressivism. But once that wears off—certainly the failure of Obamacare contributes to this, certainly the failures of the Sanders-Warren wing of the party have contributed to this—as those narratives have been sloughed off and abandoned as impractical (more accurately, as counterproductive), you see a new form of left-wing nihilism, which is the other side of the coin of left-wing progressivism. “If we can’t build a healthcare system, let’s destroy the existing healthcare system”—and perhaps out of this catastrophic destruction, something better will emerge.

The reason for this is quite simple if you look at it from the outside honestly. Building a society and building a national healthcare system for 340 million people is hard. Assassinating an unsuspecting individual on the streets of Manhattan is relatively easy. So the energy gets directed into that direction because the energy seeks opportunity, and then whatever psychopathology that is living inside these individuals—and certainly, Luigi Mangione had some psychopathology living inside of him—can then use those narratives as an intellectual rationalization. He’s a smart person. He was seeking some rationale for what is likely a complex mix of ideological and personal reasons why he wanted to commit this crime.

What’s the big problem with this is obviously the murder. You should not murder people for no reason on the streets of Manhattan. This is obvious, although not as obvious as it should be. Some people are really struggling with that. But the second problem, and the deeper problem, is that it reveals the extent to which madness and nihilism have been baked into our culture. Someone who is an Ivy League graduate, someone who has a strong family network, someone who has wealth and health and opportunity ahead of him decides to go down this dark path. That’s why there’s a fascination about this case. If it was an unknown, anonymous vagrant who stabbed someone in the street, it’s a blip. But we’ve raised the stakes, because what this shows—and for those of us in the media who share the same kind of educational background as this individual, as both of these individuals—it creates this window that America’s elite is simultaneously failing to restrain the psychopathologies of too many young people, and that the elite ideologies—both the elite ideologies that are more conventional and the elite ideologies that are even more radical—offer no path of constructive action. In fact, they are preying on people who, for their own reasons, are feeling a sense of rage, a sense of destructiveness, a sense of passion. It gives them the keys and the language to act on that in highly symbolic ways, but nonetheless extremely destructive ways.

There’s a cynical element to this as well because those political actors on the left, while saying, “Oh, I condemn violence. Violence is bad. Murder is not okay”—that perfunctory caveat—they’re saying, “Well, maybe he had a point. Maybe the insurance executive had it coming. Maybe our healthcare system is broken.” What they’re doing is they’re harvesting psychopathology. They’re harvesting seemingly random acts of violence, and they’re using them as ammunition for their own political campaigns. They’re using the spectacle, this bloodthirsty spectacle, committed by a handsome, well-educated, intelligent young man, in order to advance progressivism on the back of nihilism.

Secondly, beyond the individual dynamics, what does this case represent as a whole? It represents a unique historical transition in our time from historical idealistic leftism to a historical nihilistic leftism. What I mean by that is really important. We’ve seen, especially this past few months, what I think of as the exhaustion of the BLM mass movement. BLM as a particular mass movement is finished. We saw that with the Daniel Penny verdict in New York this week. But what happens after the splintering, the self-devouring, and the self-destruction of left-wing mass movements is that they splinter into a multiplicity of fringe movements, and fringe movements even at the level of one individual…

Watch with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Christopher F. Rufo to watch this video and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.

A subscription gets you:

| Weekly podcast | |

| Subscribers-only Q&A | |

| Behind-the-scenes access |

Christopher Rufo

Radical Normie Terrorism

Why are Middle American families producing monsters?

In the 1960s and 1970s, America witnessed a wave of political terrorism. Left-wing radicals hijacked airplanes, set bombs in government buildings, and assassinated police officers in service of political goals. The perpetrators were almost always organized, belonging to groups like the Weathermen or the Black Liberation Army. These groups demanded the release of prisoners, denounced capitalism, or called for violent revolution against the United States. Their members were radical but largely lucid, justifying their actions with appeals to a higher cause.

In recent years, a new form of terror has emerged: decentralized, digitally driven violence organized not around coherent ideologies but around memes, fantasies, and nihilistic impulses. The perpetrators of this low-grade terror campaign do not belong to hierarchical organizations or pursue concrete political aims. More often, they come from ordinary families and lash out in acts of violence without discernible purpose.

At the close of this summer, two such incidents underscored the trend: the attack on schoolchildren at Annunciation Catholic Church in Minneapolis, Minnesota, and the assassination of Charlie Kirk in Orem, Utah. Though the first resembled the school-shooter archetype and the second evoked a JFK-style political assassination, both share psychological and sociological roots that make them more alike than they initially appear.

The new terror campaign is defined by a particular kind of psychopathology. It is perhaps tautological that anyone willing to kill innocent schoolchildren as they are praying or to assassinate a popular podcast host in broad daylight is pathological. But in these cases, both alleged killers—Robin Westman (formerly Robert Westman), and Tyler Robinson—left behind several warning signs that were psychological in nature.

Westman, the alleged Annunciation shooter, left a diary detailing fantasies and inner turmoil related to his transgender identity. While he decorated his weapons with pithy slogans, including “Kill Donald Trump,” “Burn Israel,” and “Nuke India,” these were memes and ironies, designed to give the appearance of ideology, concealing a potentially more disturbing motive. He was in the throes of a transgender identity crisis and had fantasized about being a demon and wanting to watch children suffer. The ideology was a brittle shell around a deeper emptiness that could only be satisfied with horror.

Robinson, Charlie Kirk’s alleged assassin, reportedly spent thousands of hours playing video games, had an account on sexual fetish websites, and played a “dating simulator” game involving “furries,” muscular cartoon characters that are half-animal and half-man. Officials claim that Robinson had moved in with a boyfriend who identified as transgender and to whom he confessed the crime. Like Westman, Robinson inscribed slogans on the shell casings he used in the assassination, including a message about noticing the “bulge” of male genitalia through women’s clothing. The fact that Robinson waited until Kirk began to answer a question about transgender mass shootings seems to reinforce the point.

In addition to their shared fixation with transgenderism, both Westman and Robinson immersed themselves in peculiar digital subcultures. These online spaces were not hubs of Marxism—or even transgenderism, strictly speaking—but of memes, attitudes, copycatting, in-jokes, and irony that, in certain cases, spilled over into violence. Both men allegedly acted out their fantasies not to advance a coherent ideology shaped by study or political organizing but to gratify an obscure personal urge.

In a note to his transgender boyfriend, Robinson wrote that he wanted to stop Charlie Kirk’s “hate.” While this may hint at a nascent ideology, the remark was perfunctory and incidental to the crime. Robinson did not seek to change policy or dismantle a system of government. He seems instead to have wanted to kill a man who spoke openly about transgenderism and embodied a vague notion of “hate.”

Another striking pattern in these crimes is that, at least from initial reporting, the alleged perpetrators came from ordinary, middle-class, Middle American families. Westman’s mother, for example, was active in her Catholic parish in Minneapolis. These were not visibly broken homes but functional households that nonetheless produced monsters—what we might call “radical normie terrorism.”

Radical normie terrorism poses a new challenge for law enforcement. As a veteran FBI agent told me, domestic law enforcement has no systematic program to identify, assess, and respond to this kind of online radicalization. The Bureau still relies on old-fashioned methods—processing tips, knocking on doors, interviewing witnesses—and, in most cases, cannot intervene against disturbed individuals until after they strike.

These acts of terror reflect something dark in our nation’s soul. The perpetrators were so dissatisfied with their middle-class lives that they sought to destroy the highest symbols of their society: murdering children in church pews, an attack on God; and murdering a political speaker in cold blood, an attack on the republic.

Stopping similar killers in the future will be a major challenge. The Internet is hard to police and culture hard to reform. But we should keep the stakes in mind as we work to protect the things we love and grapple for a solution, however elusive it may seem.

Invite your friends and earn rewards

Christopher Rufo

Charlie Kirk Did It All the Right Way

He exposed the lies at the heart of radical left-wing ideologies—and paid the ultimate price for telling the truth.

Like almost everyone in my circle, I have spent the better part of the last week in a stupor. The news of conservative activist Charlie Kirk’s assassination has left all of us who counted him as a friend or colleague in a state of shock and sadness.

I did not know Charlie Kirk well. But I had met him in various green rooms, appeared on his radio program, and worked with him to find capable staffers for the Department of Education. He was always genuine, idealistic, and dedicated to the cause. I’m still astonished by all that he accomplished in such a short period of time. He built an enormous organization, turned himself into a media star, advised the president of the United States, and built a beautiful family—all by age 31.

When we are in the fray of day-to-day politics, it is easy to get consumed by each new headline and triviality. But Kirk’s death marks a pivotal moment, requiring deeper reflection. His life, and tragically his death, reveal some profound truths about the man and about America.

First and foremost, Charlie Kirk did it all the right way. He was a conservative willing to wade into controversial territory. But he was always guided by the idea that debate is the great clarifier and that, in a democratic society, persuasion is the primary means of political change. He set up tables on campus. He debated his opponents. And he believed he could win through the ballot box.

Kirk’s death, and the subsequent reaction to it by the radical Left, underscored the arguments he had made during his time on the stage. For nearly ten years, Kirk had argued that transgender ideology, especially when paired with experimental medical procedures, would result in disaster. From the reports now emerging, it appears likely that the alleged assassin, Tyler Robinson, was radicalized online into anti-fascist and transgender politics. In their most extreme forms, both lines of thinking advocate a nihilistic embrace of violence—the antithesis of Kirk’s approach.

In fact, when he was murdered, Kirk was answering a question about the relationship between transgenderism and mass shootings, a phenomenon that seems to have accelerated in recent years. Kirk sought to engage his opponents in debate; his killer, quite possibly inspired by the trans-radical movement, sought to end that debate with a bullet.

The reaction to Kirk’s death by the mainstream Left has been equally troubling. Thousands of Americans, including students, professors, and even active-duty military members, have publicly cheered his assassination. Some have called for further violence against conservatives. Though I have covered left-wing radical movements for years, I was surprised by the number of people in the “helping professions,” including teachers and doctors, who embraced violent rhetoric.

How should conservatives respond? First, by drawing a line that Kirk himself exemplified: debate is healthy; violence is unacceptable. I’m glad to see that some institutions have terminated the employment of those who cheered on Kirk’s murder.

Contrary to the criticism that this represents a form of right-wing “cancel culture,” these firings were warranted. During the “woke” era, left-wing social media mobs sought the social annihilation of teenagers who sang rap lyrics and a Latino utility worker who cracked his knuckles the wrong way—examples of extreme and unjustified social policing. By contrast, a public school dismissing a teacher for applauding political assassination is a fair consequence.

All societies require boundaries. If there is no social sanction for celebrating violence, America will become a more dangerous place. Social trust, already fragile, will collapse.

On the question of transgender ideology, more information will emerge about Kirk’s alleged killer. But more than enough evidence already exists for federal law enforcement to consider radical transgender ideologues a threat to the civil order of the United States—much like white nationalists, neo-Nazis, militant “anti-fascists,” and other hateful groups. Some figures in the Trump administration, such as policy adviser Stephen Miller and Vice President J. D. Vance, have already indicated that they are ready to take action to enforce the law against violent movements.

Charlie Kirk sacrificed his life for truth. We should honor his legacy by standing firmly on principle, engaging in political debate, and, when necessary, enforcing the law against those who would organize violence in the name of politics.

-

International4 hours ago

International4 hours agoBBC boss quits amid scandal over edited Trump footage

-

Daily Caller3 hours ago

Daily Caller3 hours agoMcKinsey outlook for 2025 sharply adjusts prior projections, predicting fossil fuels will dominate well after 2050

-

Agriculture6 hours ago

Agriculture6 hours agoFarmers Take The Hit While Biofuel Companies Cash In

-

Frontier Centre for Public Policy5 hours ago

Frontier Centre for Public Policy5 hours agoNotwithstanding Clause Is Democracy’s Last Line Of Defence

-

Business2 hours ago

Business2 hours agoCarney’s Floor-Crossing Campaign. A Media-Staged Bid for Majority Rule That Erodes Democracy While Beijing Hovers

-

COVID-192 days ago

COVID-192 days agoMajor new studies link COVID shots to kidney disease, respiratory problems

-

Business2 days ago

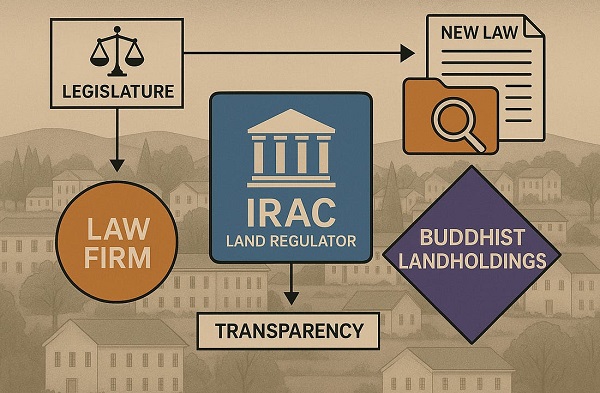

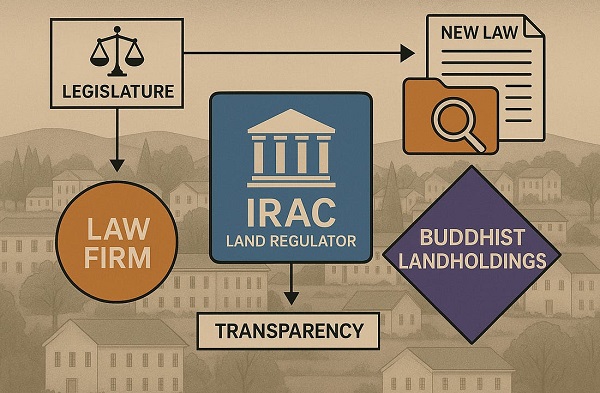

Business2 days agoP.E.I. Moves to Open IRAC Files, Forcing Land Regulator to Publish Reports After The Bureau’s Investigation

-

Energy2 days ago

Energy2 days agoCanada’s oilpatch shows strength amid global oil shakeup