Opinion

Is it time to impose term limits at city hall? A historical perspective.

If you were to look at the list of councillors (aldermen) for Red Deer from 1901 to 2017 you will find a list of 162 names.

162 people served for a total of 748 years. This averages out to 4.6 years per person. Larry Pimm and Dennis Moffat each served 27 years and you remove their years from the mix you would have 160 people serving a total of 694 years for an average of 4.3 years.

14 out 162 served for more than ten years for a total of 174 years. Take them out of the equation and you will see that 148 people served 574 years or about 3.9 – 4 years.

44 people served one year leaving a total of 104 people to serve 530 years or about 5 years each.

Many of these went on to serve as mayor and are not included in the totals.

So for 117 years we have been able to maintain a steady turnover of councillors about every 5 years. Now the term length is 4 years instead of 3 years I think it will increase. Many may find that a 4 year second term is too long and retire after 1 term.

In either case, being 3 years or 4 years, the average is less than 2 terms.

Red Deer has various council committees or boards and for example the Subdivision and Development Appeal Board you can only sit as a volunteer for 3 terms or 6 years in a row maximum. There are good reasons for limiting time served and encouraging turnover and the councillors imposed time limits.

Would these same reasons apply somewhat to city council and should they not have term limits? Should we not maintain a steady turnover in council?

Red Deer’s last municipal census showed there 99,832 residents so I am quite sure there are enough solid citizens to continue a turnover every 5 years. We have 8 councillors and if we were to turnover 5 councillors every election with a 2 term limit we would average a turnover every 5.5 years.

Currently the average amongst the incumbents is about 8 years between 4-13 years and looks like almost all of them are seeking re-election and they have the odds greatly in their favor and perhaps only 1 challenger winning a seat. So by the next election the average will be around 11 years. The trend appears to be going up for years served and down for turnover.

If we were to have 3 terms as a limit and acquire 2 or 3 newcomers every election the average will still be 9 years or nearly twice the historical average. If we had 2 term limits and we replaced 4 councillors every election the average would still be 6 years per person, still above historical average.

I think that a 2 term limit or 8 years would work and I am willing to accept a trial of 3 term limit or 12 years.

The support network is there so if all 8 councillors decided to retire on the same day, the city could easily find 8 replacements and survive. Might be some short term problems but the city will survive.

Should we talk about it?

armed forces

The Liberal Government Just Betrayed Veterans. Again. Right Before Remembrance Day.

$3.97 BILLION Cut From Veterans Affairs. Cannabis Benefits Slashed. Hypocrisy in Full Bloom.

They’re quietly dismantling the only lifeline veterans have left. The federal government just carved $3.97 billion out of Veterans Affairs Canada’s budget.

That’s not trimming fat, that’s cutting into the bone and burning the body.

And as if that weren’t disgusting enough, they’re also slashing medical cannabis reimbursements for veterans from $8.50 down to $6.00 per gram.

Kelsi Sheren is a reader-supported publication.

To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

The same medicine that’s keeping thousands of veterans alive through PTSD, chronic pain, and TBI recovery gutted by bureaucrats who’ve never had to bury a friend who lost the battle at home.

I testified in Canada’s first veteran suicide study and I warned them. I sat in front of Parliament and told them this would happen. I told them this LAST WEEK. I told them veterans were being failed by their own government ignored, delayed, and dismissed until they broke.

The study exposed it the chronic failure of the liberal veteran system. Suicide rates among veterans were higher than the national average. VAC systems were drowning in paperwork and apathy. Those who found stability through medical cannabis were finally regaining their lives.

So what did this government do with that data?

They buried it then cut the funding anyway.

This isn’t mismanagement. It’s betrayal with a signature and a smile while they wear a poppy and pretend to smile for photo ops. Jill McKnight and Mark Carney need to be held accountable for this. Canadians will DIE. Make no mistake.

This week, cannabis providers like MyMedi.ca confirmed what Ottawa buried in bureaucratic language:

“The Federal Government released its potential new budget, which includes a proposed policy change reducing the Veterans Affairs Canada reimbursement rate for medical cannabis from $8.50 per gram to $6.00 per gram.”

That’s a 30% cut to a life-saving medicine. It forces veterans to downgrade their treatment or pay out of pocket, the empty pockets that is. Standing in food bank lines and now having to find medicine on the black market to be able to function.

To justify it, the Liberals cited “declining market prices.” Let’s get one thing straight, recreational weed is not medical cannabis.

Medical cannabis is pharmaceutical-grade regulated for purity, potency, and consistency. It’s prescribed by doctors, not dealers. It’s the difference between numbing your pain and healing from it. Cutting that is like telling a diabetic to use cheaper insulin or less of it because the government found a “better price.”

It’s criminal, make no mistake.

Every November, the liberal government stands at podiums wrapped in poppies, preaching about “honouring our heroes.”

Then, when the cameras turn off, they quietly gut the budget that keeps those heroes alive.

They say they’re increasing “overall government spending” by $141 billion over the next five years. Yet they’re carving out $4 billion from the very department that’s supposed to prevent veteran suicide.

They can find billions for consultants, media subsidies, and overseas virtue projects but not to keep veterans from killing themselves. That’s not just hypocrisy. That’s moral rot and our government needs to be dismantled, held accountable and re built.

This is what corruption looks like, it’s just in polite Canadian form. There doesn’t need to be a bribe to call it corruption. Corruption is when a government pretends to care while quietly dismantling the systems that hold lives together.

Corruption is cutting medical support for veterans, then gaslighting the public with talk of “efficiency.” Corruption is using Remembrance Day for photo ops while veterans wait years for their disability claims.

Every one of these decisions sends a message – You were useful once. Now you’re expensive.

Every dollar cut equals blood on their hands and it will be your fault.

I will tell anyone who wants to join: don’t.

They will leave you to die, and step over your body to hand an immigrant your benefits the ones you fought your whole career for. This isn’t abstract. This isn’t about numbers on a spreadsheet. Every cut means, longer delays for mental health treatment. More vets turning to opioids or alcohol.

More suicides that could have been prevented. More suicides, MORE SUICIDES, MORE SUICIDES!!!

And when those suicides happen, the same politicians will stand at the next memorial and talk about “honour” while wearing crocodile tears.

Fucking liars.

Veterans aren’t asking for charity. We’re demanding the promises that were made.

If this government truly cared, they’d fund what works, not gut it. What they just did says everything. They’d protect cannabis access, streamline claims, fund the psychedelic assisted life saving therapy and actually listen to the data from the studies they commissioned.

Instead, they’re too busy protecting their image.

This isn’t about politics anymore. It’s about integrity. A country that forgets its warriors doesn’t deserve to be called free.

We fought for this land, bled for it, and came home to a system that’s now turning its back on us. No more quiet compliance. No more polite outrage.

Somewhere in this country a country that used to look and act like Canada a veteran won’t make it to morning.

A family will lose their loved one. Children will grow up without a parent. And the void they leave will never, ever be filled.

It won’t be because they were weak. Not because they didn’t try every minute of every day just to keep breathing.

It’ll be because a country that sent them to war and keeps sending kids to wars built on lies refused to bring them all the way home.

Canadians veterans are officially being left to die.

And the liberals are holding the knife.

KELSI SHEREN

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

Support the show here! – Paypal – https://paypal.me/

Buy me a coffee! – https://buymeacoffee.com/

Subscribe, like and comment! Let’s connect!

Youtube – https://www.youtube.com/@

Substack: https://substack.com/@

TikTok – https://x.com/KelsiBurns

Listen on Spotify –

|

|

The Kelsi Sheren Perspective

Kelsi Sheren Podcast |

Listen on Apple:

|

|

The Kelsi Sheren Perspective

Kelsi Sheren 310 episodes |

Censorship Industrial Complex

School Cannot Force Students To Use Preferred Pronouns, US Federal Court Rules

From the Daily Caller News Foundation

“Our system forbids public schools from becoming ‘enclaves of totalitarianism.’”

A federal appeals court in Ohio ruled Thursday that students cannot be forced to use preferred pronouns in school.

Defending Education (DE) filed the suit against Olentangy Local School District (OLSD) in 2023, arguing the district’s anti-harassment policy that requires students to use the “preferred pronouns” of others violates students’ First Amendment rights by “compelling students to affirm beliefs about sex and gender that are contrary to their own deeply held beliefs.” Although a lower court attempted to shoot down the challenge, the appeals court ruled in a 10-7 decision that the school cannot “wield their authority to compel speech or demand silence from citizens who disagree with the regulators’ politically controversial preferred new form of grammar.”

Because the school considers transgender students to be a protected class, students who violated the anti-harassment policy by referring to such students by their biological sex risked punishments such as suspension and expulsion, according to DE.

Dear Readers:

As a nonprofit, we are dependent on the generosity of our readers.

Please consider making a small donation of any amount here.

Thank you!

“American history and tradition uphold the majority’s decision to strike down the school’s pronoun policy,” the court wrote in its opinion. “Over hundreds of years, grammar has developed in America without governmental interference. Consistent with our historical tradition and our cherished First Amendment, the pronoun debate must be won through individual persuasion, not government coercion. Our system forbids public schools from becoming ‘enclaves of totalitarianism.’”

OLSD did not respond to the Daily Caller News Foundation’s request for comment.

“We are deeply gratified by the Sixth Circuit’s intensive analysis not only of our case but the state of student First Amendment rights in the modern era,” Nicole Neily, founder and president of DE, said in a statement. “The court’s decision – and its many concurrences – articulate the importance of free speech, the limits and perils of public schools claiming to act in loco parentis, and the critical role of persuasion – rather than coercion – in America’s public square.”

“Despite its ham-fisted attempt to moot the case, Olentangy School District was sternly reminded by the 6th circuit en banc court that it cannot force students to express a viewpoint on gender identity with which they disagree, nor extend its reach beyond the schoolhouse threshold into matters better suited to an exercise of parental authority,” Sarah Parshall Perry, vice president and legal fellow at DE, said in a statement. “A resounding victory for student speech and parental rights was long overdue for families in the school district and we are thrilled the court’s ruling will benefit others seeking to vindicate their rights in the classroom and beyond.”

-

espionage2 days ago

espionage2 days agoU.S. Charges Three More Chinese Scholars in Wuhan Bio-Smuggling Case, Citing Pattern of Foreign Exploitation in American Research Labs

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoCarney budget doubles down on Trudeau-era policies

-

Daily Caller2 days ago

Daily Caller2 days agoUN Chief Rages Against Dying Of Climate Alarm Light

-

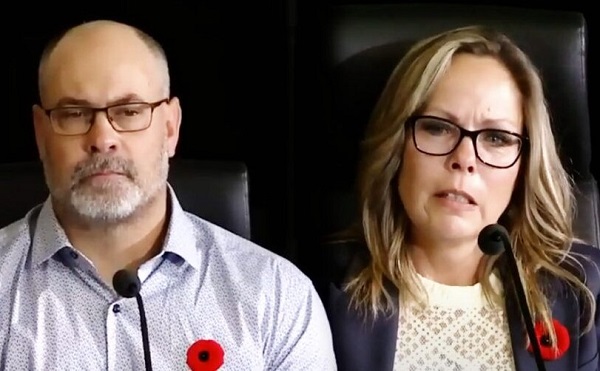

COVID-191 day ago

COVID-191 day agoCrown still working to put Lich and Barber in jail

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoCarney’s Deficit Numbers Deserve Scrutiny After Trudeau’s Forecasting Failures

-

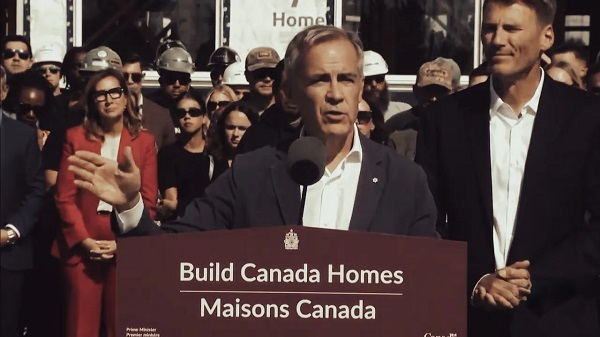

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoCarney budget continues misguided ‘Build Canada Homes’ approach

-

International1 day ago

International1 day agoKazakhstan joins Abraham Accords, Trump says more nations lining up for peace

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoU.S. Supreme Court frosty on Trump’s tariff power as world watches