Alberta

Investigation reveals terrifying life and death situation faced by police officer forced to shoot attacking suspect

Figure 1 – HAWCS video showing the AP (circled in white) driving on the wrong side of the highway and forcing a vehicle off the road.

News release from the Alberta Serious Incident Response Team (ASIRT)

ASIRT’s Investigation

ASIRT’s investigation was comprehensive and thorough, conducted using current investigative protocols, and in accordance with the principles of major case management. Investigators interviewed all relevant police and civilian witnesses, and secured and analyzed all relevant radio communications.

This incident was captured on video by a Calgary Police Service (CPS) helicopter air watch community safety (HAWCS) helicopter. Some of the incident was also captured on cameras in the RCMP vehicles. These videos provide objective evidence and are therefore extremely valuable to ASIRT investigations.

Circumstances Surrounding the Incident

At approximately 1:50 p.m. on February 12, 2023, CPS received a 9-1-1 call about the affected person (AP). The caller was concerned that she was suicidal. RCMP officers responded to an area east of Calgary, and a CPS helicopter went to assist.

At 3:35 p.m., the witness officer (WO) located the AP in her vehicle on the side of Highway 564. The AP sped off and the WO followed. The CPS helicopter located the AP and the WO shortly after and began to record the incident.

The AP was driving extremely fast, including at speeds of over 175 km/h, and often on the wrong side of the highway. There were other vehicles on the road at that time. The AP drove through a stop sign at the intersection of Highways 564 and 9 and was briefly launched into the air due to her speed and the elevated intersection. The AP continued to drive on the wrong side of the highway (Figure 1).

At Highway 21, the AP turned around and travelled back west. She then briefly went off the road and into the ditch. At 3:51 p.m., the SO used a tire deflation device that punctured some of the AP’s tires. The AP then came to a stop and, at 3:52 p.m., the SO stopped his marked police vehicle behind the AP.

As the SO stopped, the AP exited her vehicle. She had a knife in her left hand and a beer in her right (Figure 2).

Figure 2 – The SO’s vehicle video showing the AP with a knife in her left hand.

The SO can be heard to yell, “drop the knife!” on the police vehicle video. The AP took a few steps toward the SO and then began to run toward him (Figure 3).

As she was running, the AP said, “I’m going to fucking kill you!” The SO said “drop the knife” repeatedly. The SO moved backwards and drew a handgun and then a conductive energy weapon (CEW).

Figure 3 – HAWCS video showing the AP running at the SO.

The AP continued to run at the SO until she reached the rear of his police vehicle, when she turned and attempted to go into the police vehicle (Figure 4).

Figure 4 – HAWCS video showing the AP entering the SO’s police vehicle.

The SO ran back to his vehicle and used his CEW on the AP. The AP then turned and ran at the SO again (Figure 5).

Figure 5 – HAWCS video showing the AP running at the SO again.

The AP again said, “I’m going to fucking kill you!” The SO then fired seven shots at 3:53 p.m., hitting the AP and causing her to fall to the road and drop her knife (Figure 6).

The SO approached the AP and kicked away the knife. The SO began to assess the AP, and other officers arrived within one minute to provide first aid to the AP. At 4:06 p.m., emergency medical services arrived and assumed care of the AP. An air ambulance was then used to transport the AP to hospital.

The AP had seven gunshot wounds to her chest, midsection, arms, and legs. She required surgeries and stayed in the hospital for some time.

Figure 6 – HAWCS video showing the AP falling to the road after being shot by the SO.

A knife was found in the ditch near the AP (Figure 7).

Figure 7 – Knife found in ditch near the AP.

Civilian Witnesses

ASIRT investigators interviewed or reviewed interviews with eight individuals who saw the incident or the AP driving that day. Their evidence was generally consistent with the above.

Affected Person’s (AP) Statement

ASIRT investigators interviewed the AP on February 28, 2023. She told them that she was suicidal on February 12. Initially she planned to find a semi-truck to run her over.

After the WO had stopped chasing her, she turned around to reengage with the police. She drove over the tire deflation device and then pulled over. Before she left her vehicle, she grabbed a knife because she thought that the police would not shoot her unless she had something. She left her vehicle and walked fast toward the SO, saying something like “just hit me” or “shoot me.”

The SO used his CEW on her but she pushed through the pain and continued to move toward the SO. She said something like “fucking hit me you little bitch” and the SO shot her. She continued to approach the SO and he then jumped on her, taking her to the ground and injuring her leg.

The police officers provided her with medical attention immediately. She asked them to let her die.

The AP said it was her goal to die and she did not want to hurt any police officers.

Subject Officer’s (SO) Statement

On May 1, 2023, ASIRT investigators interviewed the SO. He provided a written statement and then answered questions after reading it. Subject officers, like anyone being investigated for a criminal offence, can rely on their right to silence, and do not have to speak to ASIRT.

The SO’s evidence was consistent with the video evidence and provided some insight into his view of the incident. The SO did not hear what the AP said when she was running at him. After he shot her, he heard her say things like “let me die” and “you never help me.”

When the AP was running at the SO for the second time, he recognized that he could only run backwards for so long before tripping or falling and being at risk. He feared that the AP would cause him grievous bodily harm or death and fired at the AP until she stopped advancing.

Analysis

Section 25 Generally

Under s. 25 of the Criminal Code, police officers are permitted to use as much force as is necessary for execution of their duties. Where this force is intended or is likely to cause death or grievous bodily harm, the officer must believe on reasonable grounds that the force is necessary for the self-preservation of the officer or preservation of anyone under that officer’s protection. The force used here, discharging a firearm repeatedly at a person, was clearly intended or likely to cause death or grievous bodily harm. The subject officer therefore must have believed on reasonable grounds that the force he used was necessary for his self-preservation or the preservation of another person under his protection. Another person can include other police officers. For the defence provided by s. 25 to apply to the actions of an officer, the officer must be required or authorized by law to perform the action in the administration or enforcement of the law, must have acted on reasonable grounds in performing the action, and must not have used unnecessary force.

All uses of force by police must also be proportionate, necessary, and reasonable.

Proportionality requires balancing a use of force with the action or threat to which it responds. This is codified in the requirement under s. 25(3), which states that where a force is intended or is likely to cause death or grievous bodily harm, the officer must believe on reasonable grounds that the force is necessary for the self-preservation of the officer or preservation of anyone under that officer’s protection. An action that represents a risk to preservation of life is a serious one, and only in such circumstances can uses of force that are likely to cause death or grievous bodily harm be employed.

Necessity requires that there are not reasonable alternatives to the use of force that also accomplish the same goal, which in this situation is the preservation of the life of the officer or of another person under his protection. These alternatives can include no action at all. An analysis of police actions must recognize the dynamic situations in which officers often find themselves, and such analysis should not expect police officers to weigh alternatives in real time in the same way they can later be scrutinized in a stress- free environment.

Reasonableness looks at the use of force and the situation as a whole from an objective viewpoint. Police actions are not to be judged on a standard of perfection, but on a standard of reasonableness.

Section 25 Applied

The SO was assisting on a call that evolved as time went on. It started as a welfare check, became a serious dangerous driving investigation, and ended with dealing with an assaultive person. The SO’s actions throughout were required or authorized by law and he acted on reasonable grounds.

The first stage in assessing whether the force he used was excessive is proportionality. The AP was running at the SO with a knife, which could affect the SO’s self-preservation. He responded with his firearm, which was intended or likely to cause death or grievous bodily harm. These two forces are proportionate.

The necessity element of the assessment recognizes the dynamic nature of incidents such as this. Here, the AP ran at the SO suddenly, which created a serious situation. The SO recognized at this point that he could attempt to deescalate the situation by moving away from the AP. However, the AP then attempted to get into his police vehicle, which would have created a profoundly serious danger to him and other users of the highway. He then used his CEW, which was not effective. The AP began running at him again. With the threat still present and having exhausted reasonable alternatives, it was necessary for the SO to fire at the AP at that time.

The final element, reasonableness, looks at the incident overall. The SO conducted himself carefully and showed restraint at the beginning of the incident. His actions were reasonable.

As a result, the defence under s. 25 is likely to apply to the SO.

Section 34 Generally

A police officer also has the same protections for the defence of person under s. 34 of the Criminal Code as any other person. This section provides that a person does not commit an offence if they believe on reasonable grounds that force is being used or threatened against them or another person, if they act to defend themselves or another person from this force or threat, and if the act is reasonable in the circumstances. In order for the act to be reasonable in the circumstances, the relevant circumstances of the individuals involved and the act must be considered. Section 34(2) provides a non-exhaustive list of factors to be considered to determine if the act was reasonable in the circumstances:

(a) the nature of the force or threat;

(b) the extent to which the use of force was imminent and whether there were other means available to respond to the potential use of force;

(c) the person’s role in the incident;

(d) whether any party to the incident used or threatened to use a weapon;

(e) the size, age, gender and physical capabilities of the parties to the incident;

(f) the nature, duration and history of any relationship between the parties to the incident, including any prior use or threat of force and the nature of that force or threat;

(f.1) any history of interaction or communication between the parties to the incident;

(g) the nature and proportionality of the person’s response to the use or threat of force; and

(h) whether the act committed was in response to a use or threat of force that the person knew was lawful.

The analysis under s. 34 for the actions of a police officer often overlaps considerably with the analysis of the same actions under s. 25.

Section 34 Applied

For the same reasons as under s. 25, this defence is likely to apply to the SO. The AP was running at him with a knife and, like anyone would be, he was entitled to use force to repel her.

Conclusion

The AP was suicidal on February 12, 2023. She initially intended to drive into a semi- truck, but then decided to force police to shoot her. She did this by running at the SO with a knife in her hand. The SO was justified in responding with his firearm.

The defences available to the SO under s. 25 and s. 34 are likely to apply. As a result, there are no reasonable grounds to believe that an offence was committed.

Alberta

Alberta project would be “the biggest carbon capture and storage project in the world”

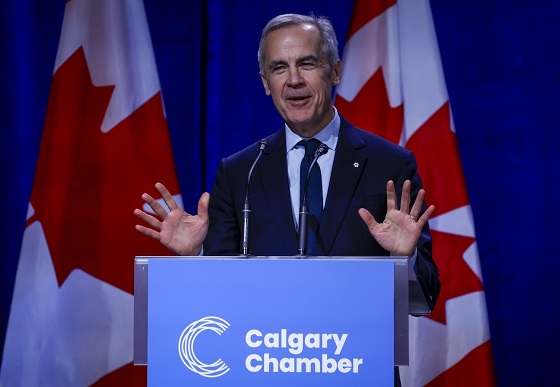

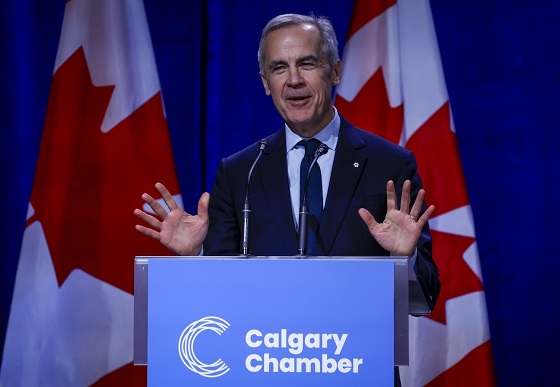

Pathways Alliance CEO Kendall Dilling is interviewed at the World Petroleum Congress in Calgary, Monday, Sept. 18, 2023.THE CANADIAN PRESS/Jeff McIntosh

From Resource Works

Carbon capture gives biggest bang for carbon tax buck CCS much cheaper than fuel switching: report

Canada’s climate change strategy is now joined at the hip to a pipeline. Two pipelines, actually — one for oil, one for carbon dioxide.

The MOU signed between Ottawa and Alberta two weeks ago ties a new oil pipeline to the Pathways Alliance, which includes what has been billed as the largest carbon capture proposal in the world.

One cannot proceed without the other. It’s quite possible neither will proceed.

The timing for multi-billion dollar carbon capture projects in general may be off, given the retreat we are now seeing from industry and government on decarbonization, especially in the U.S., our biggest energy customer and competitor.

But if the public, industry and our governments still think getting Canada’s GHG emissions down is a priority, decarbonizing Alberta oil, gas and heavy industry through CCS promises to be the most cost-effective technology approach.

New modelling by Clean Prosperity, a climate policy organization, finds large-scale carbon capture gets the biggest bang for the carbon tax buck.

Which makes sense. If oil and gas production in Alberta is Canada’s single largest emitter of CO2 and methane, it stands to reason that methane abatement and sequestering CO2 from oil and gas production is where the biggest gains are to be had.

A number of CCS projects are already in operation in Alberta, including Shell’s Quest project, which captures about 1 million tonnes of CO2 annually from the Scotford upgrader.

What is CO2 worth?

Clean Prosperity estimates industrial carbon pricing of $130 to $150 per tonne in Alberta and CCS could result in $90 billion in investment and 70 megatons (MT) annually of GHG abatement or sequestration. The lion’s share of that would come from CCS.

To put that in perspective, 70 MT is 10% of Canada’s total GHG emissions (694 MT).

The report cautions that these estimates are “hypothetical” and gives no timelines.

All of the main policy tools recommended by Clean Prosperity to achieve these GHG reductions are contained in the Ottawa-Alberta MOU.

One important policy in the MOU includes enhanced oil recovery (EOR), in which CO2 is injected into older conventional oil wells to increase output. While this increases oil production, it also sequesters large amounts of CO2.

Under Trudeau era policies, EOR was excluded from federal CCS tax credits. The MOU extends credits and other incentives to EOR, which improves the value proposition for carbon capture.

Under the MOU, Alberta agrees to raise its industrial carbon pricing from the current $95 per tonne to a minimum of $130 per tonne under its TIER system (Technology Innovation and Emission Reduction).

The biggest bang for the buck

Using a price of $130 to $150 per tonne, Clean Prosperity looked at two main pathways to GHG reductions: fuel switching in the power sector and CCS.

Fuel switching would involve replacing natural gas power generation with renewables, nuclear power, renewable natural gas or hydrogen.

“We calculated that fuel switching is more expensive,” Brendan Frank, director of policy and strategy for Clean Prosperity, told me.

Achieving the same GHG reductions through fuel switching would require industrial carbon prices of $300 to $1,000 per tonne, Frank said.

Clean Prosperity looked at five big sectoral emitters: oil and gas extraction, chemical manufacturing, pipeline transportation, petroleum refining, and cement manufacturing.

“We find that CCUS represents the largest opportunity for meaningful, cost-effective emissions reductions across five sectors,” the report states.

Fuel switching requires higher carbon prices than CCUS.

Measures like energy efficiency and methane abatement are included in Clean Prosperity’s calculations, but again CCS takes the biggest bite out of Alberta’s GHGs.

“Efficiency and (methane) abatement are a portion of it, but it’s a fairly small slice,” Frank said. “The overwhelming majority of it is in carbon capture.”

From left, Alberta Minister of Energy Marg McCuaig-Boyd, Shell Canada President Lorraine Mitchelmore, CEO of Royal Dutch Shell Ben van Beurden, Marathon Oil Executive Brian Maynard, Shell ER Manager, Stephen Velthuizen, and British High Commissioner to Canada Howard Drake open the valve to the Quest carbon capture and storage facility in Fort Saskatchewan Alta, on Friday November 6, 2015. Quest is designed to capture and safely store more than one million tonnes of CO2 each year an equivalent to the emissions from about 250,000 cars. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Jason Franson

Credit where credit is due

Setting an industrial carbon price is one thing. Putting it into effect through a workable carbon credit market is another.

“A high headline price is meaningless without higher credit prices,” the report states.

“TIER credit prices have declined steadily since 2023 and traded below $20 per tonne as of November 2025. With credit prices this low, the $95 per tonne headline price has a negligible effect on investment decisions and carbon markets will not drive CCUS deployment or fuel switching.”

Clean Prosperity recommends a kind of government-backstopped insurance mechanism guaranteeing carbon credit prices, which could otherwise be vulnerable to political and market vagaries.

Specifically, it recommends carbon contracts for difference (CCfD).

“A straight-forward way to think about it is insurance,” Frank explains.

Carbon credit prices are vulnerable to risks, including “stroke-of-pen risks,” in which governments change or cancel price schedules. There are also market risks.

CCfDs are contractual agreements between the private sector and government that guarantees a specific credit value over a specified time period.

“The private actor basically has insurance that the credits they’ll generate, as a result of making whatever low-carbon investment they’re after, will get a certain amount of revenue,” Frank said. “That certainty is enough to, in our view, unlock a lot of these projects.”

From the perspective of Canadian CCS equipment manufacturers like Vancouver’s Svante, there is one policy piece still missing from the MOU: eligibility for the Clean Technology Manufacturing (CTM) Investment tax credit.

“Carbon capture was left out of that,” said Svante co-founder Brett Henkel said.

Svante recently built a major manufacturing plant in Burnaby for its carbon capture filters and machines, with many of its prospective customers expected to be in the U.S.

The $20 billion Pathways project could be a huge boon for Canadian companies like Svante and Calgary’s Entropy. But there is fear Canadian CCS equipment manufacturers could be shut out of the project.

“If the oil sands companies put out for a bid all this equipment that’s needed, it is highly likely that a lot of that equipment is sourced outside of Canada, because the support for Canadian manufacturing is not there,” Henkel said.

Henkel hopes to see CCS manufacturing added to the eligibility for the CTM investment tax credit.

“To really build this eco-system in Canada and to support the Pathways Alliance project, we need that amendment to happen.”

Resource Works News

Alberta

The Canadian Energy Centre’s biggest stories of 2025

From the Canadian Energy Centre

Canada’s energy landscape changed significantly in 2025, with mounting U.S. economic pressures reinforcing the central role oil and gas can play in safeguarding the country’s independence.

Here are the Canadian Energy Centre’s top five most-viewed stories of the year.

5. Alberta’s massive oil and gas reserves keep growing – here’s why

The Northern Lights, aurora borealis, make an appearance over pumpjacks near Cremona, Alta., Thursday, Oct. 10, 2024. CP Images photo

Analysis commissioned this spring by the Alberta Energy Regulator increased the province’s natural gas reserves by more than 400 per cent, bumping Canada into the global top 10.

Even with record production, Alberta’s oil reserves – already fourth in the world – also increased by seven billion barrels.

According to McDaniel & Associates, which conducted the report, these reserves are likely to become increasingly important as global demand continues to rise and there is limited production growth from other sources, including the United States.

4. Canada’s pipeline builders ready to get to work

Canada could be on the cusp of a “golden age” for building major energy projects, said Kevin O’Donnell, executive director of the Mississauga, Ont.-based Pipe Line Contractors Association of Canada.

That eagerness is shared by the Edmonton-based Progressive Contractors Association of Canada (PCA), which launched a “Let’s Get Building” advocacy campaign urging all Canadian politicians to focus on getting major projects built.

“The sooner these nation-building projects get underway, the sooner Canadians reap the rewards through new trading partnerships, good jobs and a more stable economy,” said PCA chief executive Paul de Jong.

3. New Canadian oil and gas pipelines a $38 billion missed opportunity, says Montreal Economic Institute

Steel pipe in storage for the Trans Mountain Pipeline expansion in 2022. Photo courtesy Trans Mountain Corporation

In March, a report by the Montreal Economic Institute (MEI) underscored the economic opportunity of Canada building new pipeline export capacity.

MEI found that if the proposed Energy East and Gazoduq/GNL Quebec projects had been built, Canada would have been able to export $38 billion worth of oil and gas to non-U.S. destinations in 2024.

“We would be able to have more prosperity for Canada, more revenue for governments because they collect royalties that go to government programs,” said MEI senior policy analyst Gabriel Giguère.

“I believe everybody’s winning with these kinds of infrastructure projects.”

2. Keyera ‘Canadianizes’ natural gas liquids with $5.15 billion acquisition

Keyera Corp.’s natural gas liquids facilities in Fort Saskatchewan, Alta. Photo courtesy Keyera Corp.

In June, Keyera Corp. announced a $5.15 billion deal to acquire the majority of Plains American Pipelines LLP’s Canadian natural gas liquids (NGL) business, creating a cross-Canada NGL corridor that includes a storage hub in Sarnia, Ontario.

The acquisition will connect NGLs from the growing Montney and Duvernay plays in Alberta and B.C. to markets in central Canada and the eastern U.S. seaboard.

“Having a Canadian source for natural gas would be our preference,” said Sarnia mayor Mike Bradley.

“We see Keyera’s acquisition as strengthening our region as an energy hub.”

1. Explained: Why Canadian oil is so important to the United States

Enbridge’s Cheecham Terminal near Fort McMurray, Alberta is a key oil storage hub that moves light and heavy crude along the Enbridge network. Photo courtesy Enbridge

The United States has become the world’s largest oil producer, but its reliance on oil imports from Canada has never been higher.

Many refineries in the United States are specifically designed to process heavy oil, primarily in the U.S. Midwest and U.S. Gulf Coast.

According to the Alberta Petroleum Marketing Commission, the top five U.S. refineries running the most Alberta crude are:

- Marathon Petroleum, Robinson, Illinois (100% Alberta crude)

- Exxon Mobil, Joliet, Illinois (96% Alberta crude)

- CHS Inc., Laurel, Montana (95% Alberta crude)

- Phillips 66, Billings, Montana (92% Alberta crude)

- Citgo, Lemont, Illinois (78% Alberta crude)

-

International1 day ago

International1 day agoGeorgia county admits illegally certifying 315k ballots in 2020 presidential election

-

Alberta2 days ago

Alberta2 days agoAlberta project would be “the biggest carbon capture and storage project in the world”

-

Energy2 days ago

Energy2 days agoCanada’s debate on energy levelled up in 2025

-

Haultain Research1 day ago

Haultain Research1 day agoSweden Fixed What Canada Won’t Even Name

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoWhat Do Loyalty Rewards Programs Cost Us?

-

Energy2 days ago

Energy2 days agoNew Poll Shows Ontarians See Oil & Gas as Key to Jobs, Economy, and Trade

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoSocialism vs. Capitalism

-

Energy1 day ago

Energy1 day agoWhy Japan wants Western Canadian LNG