Brownstone Institute

How the Dutch Failed their Children – A Cautionary Tale

BY

One of the best places to raise children is The Netherlands. In several consecutive UNICEF reports the Netherlands ranked first for raising the happiest children among wealthy countries (2008, 2013, 2020). However, in the spring of 2020, The Netherlands became a harsh place for children and young people. The Dutch government adopted a one-size-fits-all policy handling the covid-19 pandemic, which did not spare the youngest and took a great toll on Dutch children. The Nobel Laureate Michael Levitt remarked that the Dutch policies would ‘set the record for worst covid-response ever.’

‘Intelligent Lockdown’

Unable to withstand the rising global panic, the Dutch government on March 16th 2020 announced an “intelligent” lockdown, a phrase coined by Prime Minister Mark Rutte.

Dutch society came to a halt. Offices, shops, restaurants and bars, libraries, sport facilities, as well as daycare centers, schools and universities were closed. The closure of schools was unexpected since the government’s official advisory group, the medics-dominated Outbreak Management Team (OMT), advised against it, for a school closure would have a minimal effect on the spread of the coronavirus.

A reconstruction of events showed that the main reason the Dutch government closed schools was that the educational field started to panic about keeping schools open. Closing schools was a political decision to follow the panic, not a medical decision. Schools supposedly closed for three weeks. Three weeks became three months. Research by The University of Oxford (Engzell, et al. 2021) shows that during the first wave the average Dutch student learned next to nothing during homeschooling. Moreover, students whose parents were not well-educated suffered up to 60% more learning losses.

School Closure ‘No Effect’

According to the Dutch equivalent of Fauci – Jaap van Dissel, chief scientist of the Dutch Health Agency (RIVM) and chairman of the Dutch OMT – the closure of schools in the spring of 2020 had “no effect.” Media, experts and politicians paid no attention to evidence though. Children were portrayed as ‘virus factories’ and schools were depicted as ’unsafe’ environments. Fear had a strong grip on the field of education and teaching unions exaggerated the risks of teachers in schools resulting in a drastic increase in safety demands.

The data was clear that not only did children not run any significant risk, but also that there was ‘no evidence that children play an important role in SARS-CoV-2 transmission.’ Still, a second lockdown would hit children. That second lockdown – now called a ‘hard lockdown’ – was announced on December 15th 2020. Schools closed again, this time advised by the OMT who had increased the number of areas it deemed itself expert on, on the basis of models, of course, proving Martin Kulldorff’s point that lab scientists are no public health scientists.

Dutch minister of Health Hugo de Jonge caused a stir by explaining this intervention was meant to coerce parents to stay at home. The international children’s rights organization KidsRights harshly criticized this policy: “The Netherlands has set a bad example internationally by closing schools during the corona pandemic to keep parents at home.” This children’s rights organization concluded that children were not a priority in Dutch corona policy and warned for the possible consequences.

As new insights on the negative impact of closing schools on children’s lives emerged, governments from countries all over the world decided not to close them again in the future. Undeterred, the Dutch government closed schools again on December 18 2021, just long enough to deny children their traditional Christmas dinner at school with their classmates, a big event in the childhood of Dutch children.

The deteriorating mental health of Dutch children was striking. The Dutch Health Authorities (RIVM) published a disturbing report which stated that more than one in five (22%) teenagers and young adults between the ages of 12 and 25 seriously considered taking their own life between December 2021 and February 2022 during the third lockdown. From happiest in the world to suicidal in a matter of three lockdowns.

Record Low in Sports Participation

Not only were schools closed by diktat. For two years, sports facilities were also repeatedly forced to close. The restrictions were constantly changing, with as a low point banning parents from watching their child play sports outdoors. Once again, there was no scientific evidence that this would help minimize the spread of the virus. The result is a record low in sports participation nationwide. The Dutch Olympic Committee and the Dutch Sports Federation (NOC*NSF) were ‘particularly’ worried by the negative effect on young people’s sports participation.

The Corona Pass

So no school and no sports. Another low point with regard to children was the corona pass (Coronatoegangsbewijs) that was mandatory from September 25th, 2021 for every Dutch citizen above 12. The corona pass was required for most social activities, such as going to the movies, attending a sports game with parents, or entering the canteen at sports club with teammates to drink tea or lemonade after the match.

Unsurprisingly, there was no scientific evidence that this intervention would reduce the spread of covid-19, but the Dutch government enforced it anyway. Crucially, the corona pass required vaccination, recovery from covid-19 or a negative result from a coronavirus test taken less than 24 hours before entry. So essentially, access to social life was used by the government to blackmail Dutch children into invasive medical procedures.

The madness continued, unsupported by evidence. At one point in time, outside playgrounds for children were closed. Parents were not allowed to enter swimming pools to dress their preschoolers before and after swimming lessons. In the winter of 2020-2021 the Dutch government even went as far as trying to regulate snowball fights, by dictating that only those from the same household were allowed to participate, and that their group could not exceed a certain number.

Neither sex nor the sea were exempt from the regulators. Young adults were advised which forms of sex were recommended, bearing the 1.5 m distance rule in mind. Drones were used to prevent people from gathering on the beach. To restrict the movements of young people even further, an evening curfew was introduced. It was not supported by any scientific explanation, just “boerenverstand” (common sense) as the advisory group OMT called it.

Restricting the lives of children and young people during the pandemic should require a great deal of evidence, as well as a risk-benefit evaluation. The Swedish government decided early in January 2020 that the measures in Sweden should be evidence-based. So it kept schools open, a decision supported by the evaluation of the Swedish Corona Commission in 2022. In Norway – where schools only closed briefly – the corona commission concluded in April 2022 that the Norwegian government had not done enough to protect children and that the measures regarding children had been excessive. The Norwegians essentially took the unethical initial decision to harm children without evidence and its authorities recognized that afterwards.

Sweden’s approach to the pandemic contains inconvenient truths for the Dutch, which is why Dutch authorities ignored the evidence from Sweden (and from Norway). As the Swedish journalist and author Johan Anderberg states in the epilogue of his book The Herd:

“From a human perspective, it was easy to understand why so many were reluctant to face the numbers from Sweden. For the inevitable conclusion must be that millions of people had been denied their freedom, and millions of children had had their education disrupted, all for nothing. Who would want to be complicit in that?”

This year, my wife and I decided to spend our summer holidays in Sweden and after two years of often doubtful restrictions in our home country, the Swedish summer and the beaches of Skåne were a breath of fresh air. As a parent and a Special Needs Education Generalist (and former teacher of Physical Education) I am greatly impressed by the path chosen by The Swedish Public Health Agency and the Swedish Government as they remained focused on the health, well-being, and education of children in the process of policy-making. Anders Tegnell and his predecessor Johan Giesecke have tirelessly advocated for not disturbing the lives of children, and they have been proven right.

A very outspoken Giesecke gave his frank opinion on Swedish television: “I am a father and grandfather myself, and I feel if children are given the opportunity to receive a good education and that the risk for me to become infected with covid-19 would increase slightly, it is worth it. Their future is worth more than my future, and it’s not just about my grandchildren, it’s about all the children.”

The successful Swedish approach shows that in many countries government policies met the criteria of child abuse. A key lesson for the future is that schools should not close again in similar circumstances. The Dutch government and the OMT failed the children of their country, a dark and shameful chapter in our history that future historians will surely not look favorably upon.

All expert knowledge and wisdom that has contributed to the health and well-being of Dutch children was thrown out of the window overnight in the spring of 2020. Children and young people were made to carry the burden in order to ‘supposedly’ protect adults.

As Sunetra Gupta and many others have stated, that is the precautionary principle turned upside down. The Danish-American epidemiologist Tracy Beth Høeg rightly condemned such policies, which were also pursued in the US, by calling them: Sacrificing children’s health in the name of Health.

After two years of closing down children’s lives, I firmly believe we owe it to children and their parents to make amends for the wrongs that were done to Dutch children. Above all, Article 3 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child should never be forgotten: “In all measures concerning children, the best interests of the child must come first.” It is mind-boggling how quickly children’s rights have gone out of the window worldwide. With disastrous consequences.

For children and young people a recovery plan should focus on repairing the damage done in education, recovering sports participation, and restoring the trust in the government and institutions that they can traditionally rely on for their health and their well-being. The Netherlands should be a safe haven for children, as it used to be. Pandemic preparedness also includes watching over children’s health and well-being and in this regard the Dutch failed their children and young people. We should do better in the future. Much better.

Brownstone Institute

Bizarre Decisions about Nicotine Pouches Lead to the Wrong Products on Shelves

From the Brownstone Institute

A walk through a dozen convenience stores in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, says a lot about how US nicotine policy actually works. Only about one in eight nicotine-pouch products for sale is legal. The rest are unauthorized—but they’re not all the same. Some are brightly branded, with uncertain ingredients, not approved by any Western regulator, and clearly aimed at impulse buyers. Others—like Sweden’s NOAT—are the opposite: muted, well-made, adult-oriented, and already approved for sale in Europe.

Yet in the United States, NOAT has been told to stop selling. In September 2025, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued the company a warning letter for offering nicotine pouches without marketing authorization. That might make sense if the products were dangerous, but they appear to be among the safest on the market: mild flavors, low nicotine levels, and recyclable paper packaging. In Europe, regulators consider them acceptable. In America, they’re banned. The decision looks, at best, strange—and possibly arbitrary.

What the Market Shows

My October 2025 audit was straightforward. I visited twelve stores and recorded every distinct pouch product visible for sale at the counter. If the item matched one of the twenty ZYN products that the FDA authorized in January, it was counted as legal. Everything else was counted as illegal.

Two of the stores told me they had recently received FDA letters and had already removed most illegal stock. The other ten stores were still dominated by unauthorized products—more than 93 percent of what was on display. Across all twelve locations, about 12 percent of products were legal ZYN, and about 88 percent were not.

The illegal share wasn’t uniform. Many of the unauthorized products were clearly high-nicotine imports with flashy names like Loop, Velo, and Zimo. These products may be fine, but some are probably high in contaminants, and a few often with very high nicotine levels. Others were subdued, plainly meant for adult users. NOAT was a good example of that second group: simple packaging, oat-based filler, restrained flavoring, and branding that makes no effort to look “cool.” It’s the kind of product any regulator serious about harm reduction would welcome.

Enforcement Works

To the FDA’s credit, enforcement does make a difference. The two stores that received official letters quickly pulled their illegal stock. That mirrors the agency’s broader efforts this year: new import alerts to detain unauthorized tobacco products at the border (see also Import Alert 98-06), and hundreds of warning letters to retailers, importers, and distributors.

But effective enforcement can’t solve a supply problem. The list of legal nicotine-pouch products is still extremely short—only a narrow range of ZYN items. Adults who want more variety, or stores that want to meet that demand, inevitably turn to gray-market suppliers. The more limited the legal catalog, the more the illegal market thrives.

Why the NOAT Decision Appears Bizarre

The FDA’s own actions make the situation hard to explain. In January 2025, it authorized twenty ZYN products after finding that they contained far fewer harmful chemicals than cigarettes and could help adult smokers switch. That was progress. But nine months later, the FDA has approved nothing else—while sending a warning letter to NOAT, arguably the least youth-oriented pouch line in the world.

The outcome is bad for legal sellers and public health. ZYN is legal; a handful of clearly risky, high-nicotine imports continue to circulate; and a mild, adult-market brand that meets European safety and labeling rules is banned. Officially, NOAT’s problem is procedural—it lacks a marketing order. But in practical terms, the FDA is punishing the very design choices it claims to value: simplicity, low appeal to minors, and clean ingredients.

This approach also ignores the differences in actual risk. Studies consistently show that nicotine pouches have far fewer toxins than cigarettes and far less variability than many vapes. The biggest pouch concerns are uneven nicotine levels and occasional traces of tobacco-specific nitrosamines, depending on manufacturing quality. The serious contamination issues—heavy metals and inconsistent dosage—belong mostly to disposable vapes, particularly the flood of unregulated imports from China. Treating all “unauthorized” products as equally bad blurs those distinctions and undermines proportional enforcement.

A Better Balance: Enforce Upstream, Widen the Legal Path

My small Montgomery County survey suggests a simple formula for improvement.

First, keep enforcement targeted and focused on suppliers, not just clerks. Warning letters clearly change behavior at the store level, but the biggest impact will come from auditing distributors and importers, and stopping bad shipments before they reach retail shelves.

Second, make compliance easy. A single-page list of authorized nicotine-pouch products—currently the twenty approved ZYN items—should be posted in every store and attached to distributor invoices. Point-of-sale systems can block barcodes for anything not on the list, and retailers could affirm, once a year, that they stock only approved items.

Third, widen the legal lane. The FDA launched a pilot program in September 2025 to speed review of new pouch applications. That program should spell out exactly what evidence is needed—chemical data, toxicology, nicotine release rates, and behavioral studies—and make timely decisions. If products like NOAT meet those standards, they should be authorized quickly. Legal competition among adult-oriented brands will crowd out the sketchy imports far faster than enforcement alone.

The Bottom Line

Enforcement matters, and the data show it works—where it happens. But the legal market is too narrow to protect consumers or encourage innovation. The current regime leaves a few ZYN products as lonely legal islands in a sea of gray-market pouches that range from sensible to reckless.

The FDA’s treatment of NOAT stands out as a case study in inconsistency: a quiet, adult-focused brand approved in Europe yet effectively banned in the US, while flashier and riskier options continue to slip through. That’s not a public-health victory; it’s a missed opportunity.

If the goal is to help adult smokers move to lower-risk products while keeping youth use low, the path forward is clear: enforce smartly, make compliance easy, and give good products a fair shot. Right now, we’re doing the first part well—but failing at the second and third. It’s time to fix that.

Addictions

The War on Commonsense Nicotine Regulation

From the Brownstone Institute

Cigarettes kill nearly half a million Americans each year. Everyone knows it, including the Food and Drug Administration. Yet while the most lethal nicotine product remains on sale in every gas station, the FDA continues to block or delay far safer alternatives.

Nicotine pouches—small, smokeless packets tucked under the lip—deliver nicotine without burning tobacco. They eliminate the tar, carbon monoxide, and carcinogens that make cigarettes so deadly. The logic of harm reduction couldn’t be clearer: if smokers can get nicotine without smoke, millions of lives could be saved.

Sweden has already proven the point. Through widespread use of snus and nicotine pouches, the country has cut daily smoking to about 5 percent, the lowest rate in Europe. Lung-cancer deaths are less than half the continental average. This “Swedish Experience” shows that when adults are given safer options, they switch voluntarily—no prohibition required.

In the United States, however, the FDA’s tobacco division has turned this logic on its head. Since Congress gave it sweeping authority in 2009, the agency has demanded that every new product undergo a Premarket Tobacco Product Application, or PMTA, proving it is “appropriate for the protection of public health.” That sounds reasonable until you see how the process works.

Manufacturers must spend millions on speculative modeling about how their products might affect every segment of society—smokers, nonsmokers, youth, and future generations—before they can even reach the market. Unsurprisingly, almost all PMTAs have been denied or shelved. Reduced-risk products sit in limbo while Marlboros and Newports remain untouched.

Only this January did the agency relent slightly, authorizing 20 ZYN nicotine-pouch products made by Swedish Match, now owned by Philip Morris. The FDA admitted the obvious: “The data show that these specific products are appropriate for the protection of public health.” The toxic-chemical levels were far lower than in cigarettes, and adult smokers were more likely to switch than teens were to start.

The decision should have been a turning point. Instead, it exposed the double standard. Other pouch makers—especially smaller firms from Sweden and the US, such as NOAT—remain locked out of the legal market even when their products meet the same technical standards.

The FDA’s inaction has created a black market dominated by unregulated imports, many from China. According to my own research, roughly 85 percent of pouches now sold in convenience stores are technically illegal.

The agency claims that this heavy-handed approach protects kids. But youth pouch use in the US remains very low—about 1.5 percent of high-school students according to the latest National Youth Tobacco Survey—while nearly 30 million American adults still smoke. Denying safer products to millions of addicted adults because a tiny fraction of teens might experiment is the opposite of public-health logic.

There’s a better path. The FDA should base its decisions on science, not fear. If a product dramatically reduces exposure to harmful chemicals, meets strict packaging and marketing standards, and enforces Tobacco 21 age verification, it should be allowed on the market. Population-level effects can be monitored afterward through real-world data on switching and youth use. That’s how drug and vaccine regulation already works.

Sweden’s evidence shows the results of a pragmatic approach: a near-smoke-free society achieved through consumer choice, not coercion. The FDA’s own approval of ZYN proves that such products can meet its legal standard for protecting public health. The next step is consistency—apply the same rules to everyone.

Combustion, not nicotine, is the killer. Until the FDA acts on that simple truth, it will keep protecting the cigarette industry it was supposed to regulate.

-

Business2 days ago

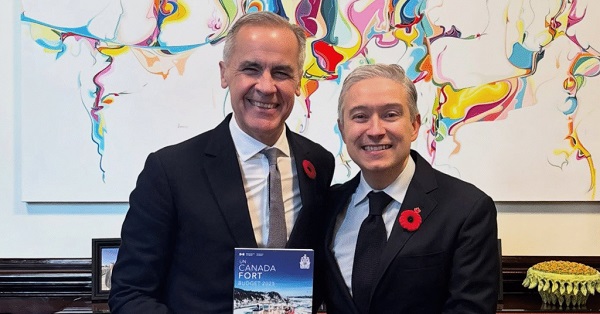

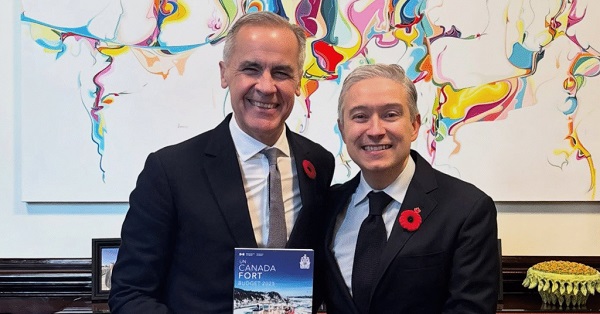

Business2 days agoCarney shrugs off debt problem with more borrowing

-

Alberta2 days ago

Alberta2 days agoWhen Teachers Say Your Child Has Nowhere Else to Go

-

Automotive2 days ago

Automotive2 days agoThe high price of green virtue

-

Addictions2 days ago

Addictions2 days agoCanada is divided on the drug crisis—so are its doctors

-

Bruce Dowbiggin2 days ago

Bruce Dowbiggin2 days agoMaintenance Mania: Since When Did Pro Athletes Get So Fragile?

-

Daily Caller2 days ago

Daily Caller2 days agoProtesters Storm Elite Climate Summit In Chaotic Scene

-

MAiD2 days ago

MAiD2 days agoQuebec has the highest euthanasia rate in the world at 7.4% of total deaths

-

National1 day ago

National1 day agoConservative bill would increase penalties for attacks on places of worship in Canada