Business

Costly construction isn’t the culprit behind unaffordable housing

From the Frontier Centre for Public Policy

By Wendell Cox

Land restriction creates what amount to land cartels. A now smaller number of landowners gain windfall profits, which, of course, encourages speculation

The latest Demographia report on housing affordability in Canada, which I produce for the Frontier Centre for Public Policy, reveals that over half of the 46 Canadian housing markets we assess are severely unaffordable. In fact, Vancouver and Toronto rank as third and 10th least affordable, respectively, among the 94 major global markets included in our latest international housing affordability study.

To evaluate housing costs, we utilize the “median multiple,” which divides the median house price within a given market (census metropolitan area) by its median household income. A multiple equal to or less than 3.0 is categorized as “affordable,” while anything exceeding 5.0 is labelled “severely unaffordable.”

Among the major Canadian housing markets, Vancouver (with a median multiple of 12), Toronto (9.5), Montreal (5.4), and Ottawa-Gatineau (5.2) fall into the severely unaffordable category. Vancouver has maintained a high median multiple for several decades, while Toronto has been in this range for approximately two decades. The increased prevalence of telecommuting has recently contributed to Montreal and Ottawa-Gatineau’s affordability challenges, leading to a surge in demand for larger homes and properties in more distant suburbs. In contrast, housing in Edmonton (4.0) and Calgary (4.3) remains comparatively affordable.

In Toronto and Vancouver, the implementation of international urban planning principles, particularly those promoting anti-sprawl measures like greenbelts and agricultural preserves, has led to unprecedented price hikes. This “urban containment” approach has consistently driven up land values where it has been adopted. And high land values rather than increased construction costs are what explain the substantial disparity between severely unaffordable and more budget-friendly markets.

Land restriction creates what amount to land cartels. A now smaller number of landowners gain windfall profits, which, of course, encourages speculation. Maintaining or restoring affordability requires eliminating windfall profits by ensuring a competitive market for land.

Another issue arises from urban planners’ preference for higher-density housing, such as high-rise condos. Some households may prefer high-rise living, but families with children typically seek housing with more land, whether detached or semi-detached. When they’re priced out of good housing markets, their quality of life suffers and they may even fall into poverty.

The troubling paradox is that unaffordable housing is far more common in markets like Vancouver and Toronto, which have embraced the planning orthodoxy — which is supposed to produce affordable housing. The same applies to international markets like Sydney, Auckland, London and San Francisco, where urban containment and unaffordable housing have gone hand in hand.

What’s the solution? Give up on urban containment and make more land available for housing. But wouldn’t that threaten the natural environment, as critics of Ontario’s recent attempt to allow development of a sliver of its greenbelt argued?

Not at all. It’s true that land under cultivation in Canada has been declining steadily over the years. But the culprit is improved agricultural productivity, not urban expansion. According to Statistics Canada, between 2001 and 2021, agricultural land shrank 53,000 square kilometres. That’s about equal to the land area of Nova Scotia. And it’s about triple all the area urbanized since European settlement began. Even in Ontario and B.C. where most of the severely unaffordable markets are concentrated, urban expansion from 2016 to 2021 took up less than one-quarter of the agricultural loss over that period. Urban expansion is not squeezing out agricultural land.

Given all this, what should we do about affordability? In my view, three things:

First, it’s essential to acknowledge that Canadians are already addressing the issue by relocating from pricier to more affordable regions. Housing is more affordable in the Atlantic and Prairie provinces and areas in Quebec east of Montreal. So it’s not surprising there is now a net influx of people to smaller, typically more affordable, locations. In the past five years, markets with populations exceeding 100,000 have collectively witnessed over 250,000 people moving to smaller markets.

Second, make more land available for development in increasingly unaffordable markets like B.C., southern Ontario, and the Montreal-Ottawa corridor. One way is with “housing opportunity enclaves” (HOEs), in which traditional, i.e., not high-density, housing regulations would apply, but essential environmental and safety regulations would. The aim would be to provide middle-income housing at the price-to-income ratios that were typical before urban containment came along and housing across the country was largely affordable.

Market-driven development would be ensured by relying on the private sector to provide housing, land, and infrastructure, a model that has been successful in Colorado and Texas. Current residents would maintain their property rights but could sell to private parties and First Nations for development.

HOEs would be situated far enough outside major centres to take advantage of low-priced land, prioritizing areas with the largest recent agricultural land reductions. Communities likely would resemble Waverly West in Winnipeg or The Woodlands in Houston, with ample housing space and yards for families with children.

These new communities would attract people working at least partly from home. Jobs would naturally follow, creating self-contained communities where most commutes occurred within the HOE. To ensure a competitive market and prevent land cost escalation, HOEs must have ample land available.

Third, public authorities should allocate an ample amount of suburban land to safeguard reasonable land values in the Prairie and Atlantic provinces, as well as in Quebec east of Montreal. This would allow currently more affordable markets such as Quebec City, Calgary, Edmonton, Winnipeg, Moncton and Halifax to accommodate interprovincial migrants without jeopardizing their affordability.

Provincial and local governments would need to monitor housing affordability multiples on at least a five-year cycle, and legislatures, land use authorities and city councils would have to allow enough low-cost land development to maintain price-to-income stability.

It’s not enough just to provide enough building lots to meet projected demand. The goal should be to enable builders to provide housing at prices middle-income households can afford. The key to that is affordable land.

Wendell Cox is a Senior Fellow at the Frontier Centre for Public Policy. He is the author of 2023 Edition Of Demographia Housing Affordability In Canada and has been featured on Leaders on the Frontier – Cost of Living Under Crisis With Charles Blain.

Business

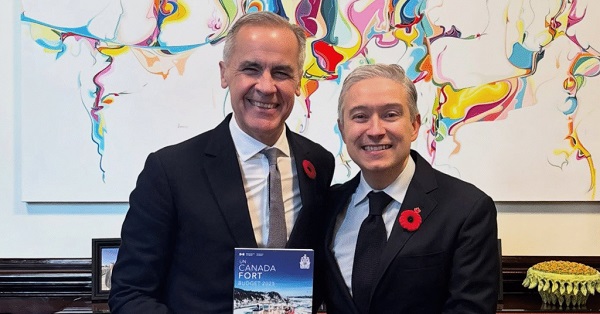

Here’s what pundits and analysts get wrong about the Carney government’s first budget

From the Fraser Institute

By Jason Clemens and Jake Fuss

Under the new budget plan, this wedge between what the government collects in revenues versus what is actually spent on programs will rise to 13.0 per cent by 2029/30. Put differently, slightly more than one in every eight dollars sent to Ottawa will be used to pay interest on debt for past spending.

The Carney government’s much-anticipated first budget landed on Nov. 4. There’s been much discussion by pundits and analysts on the increase in the deficit and borrowing, the emphasis on infrastructure spending (broadly defined), and the continued activist approach of Ottawa. There are, however, several critically important aspects of the budget that are consistently being misstated or misinterpreted, which makes it harder for average Canadians to fully appreciate the consequences and costs of the budget.

One issue in need of greater clarity is the cost of Canada’s indebtedness. Like regular Canadians and businesses, the government must pay interest on federal debt. According to the budget plan, total federal debt will reach an expected $2.9 trillion in 2029/30. For reference, total federal debt stood at $1.0 trillion when the Trudeau government took office in 2015. The interest costs on that debt will rise from $53.4 billion last year to an expected $76.1 billion by 2029/30. Several analyses have noted this means federal interest costs will rise from 1.7 per cent of GDP to 2.1 per cent.

These are all worrying statistics about the indebtedness of the federal government. However, they ignore a key statistic—interest costs as a share of revenues. When the Trudeau government took office, interest costs consumed 7.5 per cent of revenues. This means taxpayers were foregoing 7.5 per cent of the resources they sent to Ottawa (in terms of spending on actual programs) because these monies were used to pay interest on debt accumulated from previous spending.

Under the new budget plan, this wedge between what the government collects in revenues versus what is actually spent on programs will rise to 13.0 per cent by 2029/30. Put differently, slightly more than one in every eight dollars sent to Ottawa will be used to pay interest on debt for past spending. This is one way governments get into financial problems, even crises, by continually increasing the share of revenues consumed by interest payments.

A second and fairly consistently misrepresented aspect of the budget pertains to large spending initiatives such as Build Canada Homes and Build Communities Strong Fund. The former is meant to increase the number of new homes, particularly affordable homes, being built annually and the latter is intended to provide funding to provincial governments (and through them, municipalities) for infrastructure spending. But few analysts question whether or not these programs will produce actual new spending for homebuilding or simply replace or “crowd-out” existing spending by the private sector.

Let’s first explore the homebuilding initiative. At any point in time, there are a limited number of skilled workers, raw materials, land, etc. available for homebuilding. When the federal government, or any government, initiates its own homebuilding program, it directly competes with private companies for that skilled labour (carpenters, electricians, etc.), raw materials (timber, concrete, etc.) and the land needed for development. Put simply, government homebuilding crowds out private-sector activity.

Moreover, there’s a strong argument that the crowding out by government results in less homebuilding than would otherwise be the case, because the incentives for private-sector homebuilding are dramatically different than government incentives. For example, private firms risk their own wealth and wellbeing (and the wellbeing of their employees) so they have very strong incentives to deliver homes demanded by people on time and at a reasonable price. Government bureaucrats and politicians, on the other hand, face no such incentives. They pay no price, in terms of personal wealth or wellbeing if homes, are late, not what consumers demand, or even produce less than expected. Put simply, homebuilding by Ottawa could easily result in less homes being built than if government had stayed out of the way of entrepreneurs, businessowners and developers.

Similarly, it’s debatable that infrastructure spending by Ottawa—specifically, providing funds to the provinces and municipalities—results in an actual increase in total infrastructure spending. There are numerous historical examples, including reports by the auditor general, detailing how similar infrastructure spending initiatives by the federal government were plagued by mismanagement. And in many circumstances, the provinces simply reduced their own infrastructure spending to save money, such that the actual incremental increase in overall infrastructure spending was negligible.

In reality, some of the major and large spending initiatives announced or expanded in the Carney government’s first budget, which will accelerate the deterioration of federal finances, may not deliver anything close to what the government suggests. Canadians should understand the real risks and challenges in these federal spending initiatives, along with the debt being accumulated, and the limited potential benefits.

Business

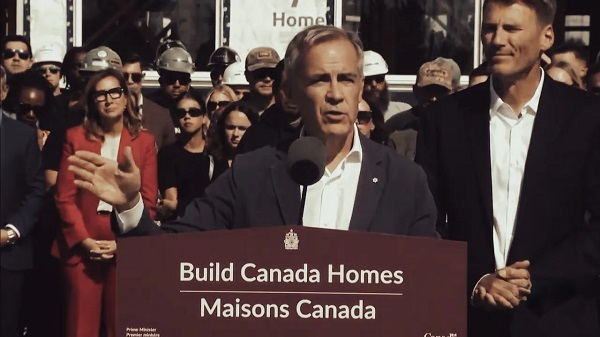

Carney budget continues misguided ‘Build Canada Homes’ approach

From the Fraser Institute

By Jake Fuss and Austin Thompson

The Carney government’s first budget tabled on Tuesday promises to “supercharge” homebuilding across the country. But Ottawa’s flagship housing initiative—a new federal agency, Build Canada Homes (BCH)—risks “supercharging” federal debt instead while doing little to boost construction.

The budget accurately diagnoses the root cause of Canada’s housing shortage—costly red tape on housing projects, sky-high taxes on homebuilders, and weak productivity growth in the construction sector. But the proposed cure, BCH, does nothing to fix these problems despite receiving a five-year budget of $13 billion.

BCH’s core mandate is to build and finance affordable housing projects. But this mission is muddled by competing political priorities to preference Canadian building materials and prioritize “sustainable” construction materials. Any product that needs a government preference to be used is clearly not the most cost-effective option. The result—BCH’s “affordable” homes will cost more than they needed to, meaning more tax dollars wasted.

Ottawa claims BCH will improve construction productivity by “generating demand” (read: splashing out tax dollars) for factory-built housing. This logic is faulty—where factory-built housing is a cost-effective and desirable option, private developers are already building it. “Prioritizing” factory-built homes amounts to Ottawa trying to pick winners and losers—a strategy that reliably wastes taxpayer dollars. The civil servants running BCH lack the market knowledge and cost-cutting incentives of private homebuilders, who are far better positioned to identify which technologies will deliver the affordable homes Canadians need.

The government also insists BCH projects will attract more private investment for housing. The opposite is more likely—BCH projects will compete with private developers for limited investment dollars and construction labour. Ottawa’s intrusion into housing development could ultimately mean fewer private-sector housing projects—those driven by the real needs of homebuyers and renters, not the Carney government’s political priorities.

Despite its huge budget and broad mandate, BCH still lacks clear goals. Its only commitment so far is to “build affordable housing at scale,” with no concrete targets for how many new homes or how affordable they’ll be. Without measurable outcomes, neither Ottawa nor taxpayers will know whether BCH delivers value for money.

You can’t solve Canada’s housing crisis with yet another federal program. Ottawa should resist the temptation to act as a housing developer and instead create fiscal and economic conditions that allow the private sector to build more homes.

-

Censorship Industrial Complex2 days ago

Censorship Industrial Complex2 days agoHow the UK and Canada Are Leading the West’s Descent into Digital Authoritarianism

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoCapital Flight Signals No Confidence In Carney’s Agenda

-

International2 days ago

International2 days agoThe capital of capitalism elects a socialist mayor

-

Energy1 day ago

Energy1 day agoEby should put up, shut up, or pay up

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoPulling back the curtain on the Carney government’s first budget

-

Daily Caller1 day ago

Daily Caller1 day agoUS Eating Canada’s Lunch While Liberals Stall – Trump Admin Announces Record-Shattering Energy Report

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoThe Liberal budget is a massive FAILURE: Former Liberal Cabinet Member Dan McTeague

-

Business22 hours ago

Business22 hours agoCarney’s budget spares tax status of Canadian churches, pro-life groups after backlash