Health

Cancer drug pioneer praises RFK Jr., suggests link between childhood cancer and COVID shots

From LifeSiteNews

Trump nominee for Secretary of Health and Human Services Robert F. Kennedy received a ringing endorsement from a medical pioneer, Dr. Patrick Soon-Shiong, who said the country needs to take seriously a possible link between the COVID-19 shots and childhood cancer.

Trump nominee for Secretary of Health and Human Services Robert F. Kennedy Jr. received a ringing endorsement from an acclaimed medical expert on Tuesday who said the country needs to take seriously a possible link between the COVID-19 shots and childhood cancer.

Dr. Patrick Soon-Shiong is a billionaire who pioneered the cancer drug Abraxane and has owned and led multiple medical companies. In 2018, he purchased the Los Angeles Times (which he blocked from endorsing Democrat Kamala Harris for president in 2024), and his ImmunityBio was among the companies recruited by the Trump administration to contribute to Operation Warp Speed.

On Tuesday, Soon-Shiong appeared on the 2WAY podcast, where he shared his thoughts about some of the big medical policy questions of the next four years.

“I think people misunderstand Bobby Kennedy, Robert F. Kennedy. He’s really all about the science,” he said. “I’ve sat down with him, met with him for the first time. I’ve not known him until I sat down with him, because I wanted to understand what he was thinking. And after hours of sitting down with him, I was so impressed. He knows more about the science than most doctors.”

Soon-Shiong went on to say “we’re going to have to address the rising incidence of cancer. For the first time in my career, I’ve seen an 8-year-old, 9-year-old, 10-year-old with colon cancer. The first time in my career, I’ve had a 13-year-old child in our clinic die of metastatic pancreatic cancer. We have to face this effectiveness and reality.”

The doctor ended on an optimistic note, saying that “there are effective therapies because we understand the science in such an immense way,” and adding that he is “excited about this next four years of bringing this information across and not to scare the population to say, look, we could lead the world in our innovation and using healthcare as a foreign policy around the world.”

A large body of evidence identifies significant risks to the COVID shots, which were developed and reviewed in a fraction of the time vaccines usually take under Operation Warp Speed.

The federal Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) reports 38,264 deaths, 219,594 hospitalizations, 22,134 heart attacks, and 28,814 myocarditis and pericarditis cases as of December 27, among other ailments. CDC researchers have recognized a “high verification rate of reports of myocarditis to VAERS after mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccination,” leading to the conclusion that “under-reporting is more likely” than over-reporting.

An analysis of 99 million people across eight countries published in February in the journal Vaccine “observed significantly higher risks of myocarditis following the first, second and third doses” of mRNA-based COVID shots, as well as signs of increased risk of “pericarditis, Guillain-Barré syndrome, and cerebral venous sinus thrombosis,” and other “potential safety signals that require further investigation.” In April, the CDC was forced to release by court order 780,000 previously undisclosed reports of serious adverse reactions, and a study out of Japan found “statistically significant increases” in cancer deaths after third doses of mRNA-based COVID-19 injections and offered several theories for a causal link.

Earlier this month, a long-awaited Florida grand jury report on the COVID shot manufacturers found that there were “profound and serious issues” in pharmaceutical companies’ review process, including reluctance to share what evidence of adverse events they found.

All eyes are currently on Trump and his health team, which will be helmed by Kennedy at HHS. As one of the country’s most vocal critics of the COVID establishment and vaccines more generally, his nomination brought hope that the second Trump administration will take a critical reassessment of the shots that the returning president has previously embraced, although most of Kennedy’s comments since joining Trump have focused on other issues, such as conventional vaccines and harmful food additives.

Trump has given mixed signals as to the prospects of reconsidering the shots and has nominated both critics and defenders of establishment COVID measures for a number of administration roles.

Addictions

‘Over and over until they die’: Drug crisis pushes first responders to the brink

First responders say it is not overdoses that leave them feeling burned out—it is the endless cycle of calls they cannot meaningfully resolve

The soap bottle just missed his head.

Standing in the doorway of a cluttered Halifax apartment, Derek, a primary care paramedic, watched it smash against the wall.

Derek was there because the woman who threw it had called 911 again — she did so nearly every day. She said she had chest pain. But when she saw the green patch on his uniform, she erupted. Green meant he could not give her what she wanted: fentanyl.

She screamed at him to call “the red tags” — advanced care paramedics authorized to administer opioids. With none available, Derek declared the scene unsafe and left. Later that night, she called again. This time, a red-patched unit was available. She got her dose.

Derek says he was not angry at the woman, but at the system that left her trapped in addiction — and him powerless to help.

First responders across Canada say it is not overdoses that leave them feeling burned out — it is the endless cycle of calls they cannot meaningfully resolve. Understaffed, overburdened and dispatched into crises they are not equipped to fix, many feel morally and emotionally drained.

“We’re sending our first responders to try and manage what should otherwise be dealt with at structural and systemic levels,” said Nicholas Carleton, a University of Regina researcher who studies the mental health of public safety personnel.

Canadian Affairs agreed to use pseudonyms for the two frontline workers referenced in this story. Canadian Affairs also spoke with nine other first responders who agreed to speak only on background. All of these sources cited concerns about workplace retaliation for speaking out.

Moral injury

Canada’s opioid crisis is pushing frontline workers such as paramedics to the brink.

A 2024 study of 350 Quebec paramedics shows one in three have seriously considered suicide. Globally, ambulance workers have among the highest suicide rates of public service personnel.

Between 2017 and 2024, Canadian paramedics responded to nearly 240,000 suspected opioid overdoses. More than 50,000 of those were fatal.

Yet many paramedics say overdose calls are not the hardest part of the job.

“When they do come up, they’re pretty easy calls,” said Derek. Naloxone, a drug that reverses overdoses, is readily available. “I can actually fix the problem,” he said. “[It’s a] bit of instant gratification, honestly.”

What drains him are the calls they cannot fix: mental health crises, child neglect and abuse, homelessness.

“The ER has a [cardiac catheterization] lab that can do surgery in minutes to fix a heart attack. But there’s nowhere I can bring the mental health patients.

“So they call. And they call. And they call.”

Thomas, a primary care paramedic in Eastern Ontario, echoes that frustration.

“The ER isn’t a good place to treat addiction,” he said. “They need intensive, long-term psychological inpatient treatment and a healthy environment and support system — first responders cannot offer that.”

That powerlessness erodes trust. Paramedics say patients with addictions often become aggressive, or stop seeking help altogether.

“We have a terrible relationship with the people in our community struggling with addiction,” Thomas said. “They know they will sit in an ER bed for a few hours while being in withdrawals and then be discharged with a waitlist or no follow-up.”

Carleton, of the University of Regina, says that reviving people repeatedly without improvement decreases morale.

“You’re resuscitating someone time and time again,” said Carleton, who is also director of the Psychological Trauma and Stress Systems Lab, a federal unit dedicated to mental health research for public safety personnel. “That can lead to compassion fatigue … and moral injury.”

Katy Kamkar, a clinical psychologist focused on first responder mental health, says moral injury arises when workers are trapped in ethically impossible situations — saving a life while knowing that person will be back in the same state tomorrow.

“Burnout is … emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal accomplishment,” she said in an emailed statement. “High call volumes, lack of support or follow-up care for patients, and/or bureaucratic constraints … can increase the risk of reduced empathy, absenteeism and increased turnover.”

Kamkar says moral injury affects all branches of public safety, not just paramedics. Firefighters, who are often the first to arrive on the scene, face trauma from overdose deaths. Police report distress enforcing laws that criminalize suffering.

Understaffed and overburdened

Staffing shortages are another major stressor.

“First responders were amazing during the pandemic, but it also caused a lot of fatigue, and a lot of people left our business because of stress and violence,” said Marc-André Périard, vice president of the Paramedic Chiefs of Canada.

Nearly half of emergency medical services workers experience daily “Code Blacks,” where there are no ambulances available. Vacancy rates are climbing across emergency services. The federal government predicts paramedic shortages will persist over the coming decade, alongside moderate shortages of police and firefighters.

Unsafe work conditions are another concern. Responders enter chaotic scenes where bystanders — often fellow drug users — mistake them for police. Paramedics can face hostility from patients they just saved, says Périard.

“People are upset that they’ve been taken out of their high [when Naloxone is administered] and not realizing how close to dying they were,” he said.

Thomas says safety is undermined by vague, inconsistently enforced policies. And efforts to collect meaningful data can be hampered by a work culture that punishes reporting workplace dangers.

“If you report violence, it can come back to haunt you in performance reviews” he said.

Some hesitate to wait for police before entering volatile scenes, fearing delayed response times.

“[What] would help mitigate violence is to have management support their staff directly in … waiting for police before arriving at the scene, support paramedics in leaving an unsafe scene … and for police and the Crown to pursue cases of violence against health-care workers,” Thomas said.

“Right now, the onus is on us … [but once you enter], leaving a scene is considered patient abandonment,” he said.

Upstream solutions

Carleton says paramedics’ ability to refer patients to addiction and mental health referral networks varies widely based on their location. These networks rely on inconsistent local staffing, creating a patchwork system where people easily fall through the cracks.

“[Any] referral system butts up really quickly against the challenges our health-care system is facing,” he said. “Those infrastructures simply don’t exist at the size and scale that we need.”

Périard agrees. “There’s a lot of investment in safe injection sites, but not as much [resources] put into help[ing] these people deal with their addictions,” he said.

Until that changes, the cycle will continue.

On May 8, Alberta renewed a $1.5 million grant to support first responders’ mental health. Carleton welcomes the funding, but says it risks being futile without also addressing understaffing, excessive workloads and unsafe conditions.

“I applaud Alberta’s investment. But there need to be guardrails and protections in place, because some programs should be quickly dismissed as ineffective — but they aren’t always,” he said.

Carleton’s research found that fewer than 10 mental health programs marketed to Canadian governments — out of 300 in total — are backed up by evidence showing their effectiveness.

In his view, the answer is not complicated — but enormous.

“We’ve got to get way further upstream,” he said.

“We’re rapidly approaching more and more crisis-level challenges… with fewer and fewer [first responders], and we’re asking them to do more and more.”

This article was produced through the Breaking Needles Fellowship Program, which provided a grant to Canadian Affairs, a digital media outlet, to fund journalism exploring addiction and crime in Canada. Articles produced through the Fellowship are co-published by Break The Needle and Canadian Affairs.

Business

Prime minister can make good on campaign promise by reforming Canada Health Act

From the Fraser Institute

While running for the job of leading the country, Prime Minister Carney promised to defend the Canada Health Act (CHA) and build a health-care system Canadians can be proud of. Unfortunately, to have any hope of accomplishing the latter promise, he must break the former and reform the CHA.

As long as Ottawa upholds and maintains the CHA in its current form, Canadians will not have a timely, accessible and high-quality universal health-care system they can be proud of.

Consider for a moment the remarkably poor state of health care in Canada today. According to international comparisons of universal health-care systems, Canadians endure some of the lowest access to physicians, medical technologies and hospital beds in the developed world, and wait in queues for health care that routinely rank among the longest in the developed world. This is all happening despite Canadians paying for one of the developed world’s most expensive universal-access health-care systems.

None of this is new. Canada’s poor ranking in the availability of services—despite high spending—reaches back at least two decades. And wait times for health care have nearly tripled since the early 1990s. Back then, in 1993, Canadians could expect to wait 9.3 weeks for medical treatment after GP referral compared to 30 weeks in 2024.

But fortunately, we can find the solutions to our health-care woes in other countries such as Germany, Switzerland, the Netherlands and Australia, which all provide more timely access to quality universal care. Every one of these countries requires patient cost-sharing for physician and hospital services, and allows private competition in the delivery of universally accessible services with money following patients to hospitals and surgical clinics. And all these countries allow private purchases of health care, as this reduces the burden on the publicly-funded system and creates a valuable pressure valve for it.

And this brings us back to the CHA, which contains the federal government’s requirements for provincial policymaking. To receive their full federal cash transfers for health care from Ottawa (totalling nearly $55 billion in 2025/26) provinces must abide by CHA rules and regulations.

And therein lies the rub—the CHA expressly disallows requiring patients to share the cost of treatment while the CHA’s often vaguely defined terms and conditions have been used by federal governments to discourage a larger role for the private sector in the delivery of health-care services.

Clearly, it’s time for Ottawa’s approach to reflect a more contemporary understanding of how to structure a truly world-class universal health-care system.

Prime Minister Carney can begin by learning from the federal government’s own welfare reforms in the 1990s, which reduced federal transfers and allowed provinces more flexibility with policymaking. The resulting period of provincial policy innovation reduced welfare dependency and government spending on social assistance (i.e. savings for taxpayers). When Ottawa stepped back and allowed the provinces to vary policy to their unique circumstances, Canadians got improved outcomes for fewer dollars.

We need that same approach for health care today, and it begins with the federal government reforming the CHA to expressly allow provinces the ability to explore alternate policy approaches, while maintaining the foundational principles of universality.

Next, the Carney government should either hold cash transfers for health care constant (in nominal terms), reduce them or eliminate them entirely with a concordant reduction in federal taxes. By reducing (or eliminating) the pool of cash tied to the strings of the CHA, provinces would have greater freedom to pursue reform policies they consider to be in the best interests of their residents without federal intervention.

After more than four decades of effectively mandating failing health policy, it’s high time to remove ambiguity and minimize uncertainty—and the potential for politically motivated interpretations—in the CHA. If Prime Minister Carney wants Canadians to finally have a world-class health-care system then can be proud of, he should allow the provinces to choose their own set of universal health-care policies. The first step is to fix, rather than defend, the 40-year-old legislation holding the provinces back.

-

COVID-192 days ago

COVID-192 days agoFDA requires new warning on mRNA COVID shots due to heart damage in young men

-

Indigenous2 days ago

Indigenous2 days agoInternal emails show Canadian gov’t doubted ‘mass graves’ narrative but went along with it

-

Bruce Dowbiggin2 days ago

Bruce Dowbiggin2 days agoEau Canada! Join Us In An Inclusive New National Anthem

-

Crime2 days ago

Crime2 days agoEyebrows Raise as Karoline Leavitt Answers Tough Questions About Epstein

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoCarney’s new agenda faces old Canadian problems

-

Alberta2 days ago

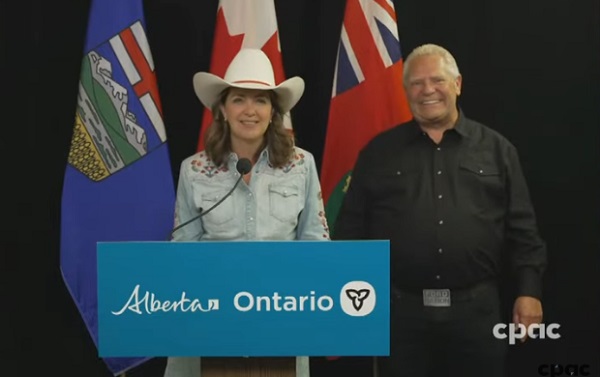

Alberta2 days agoAlberta and Ontario sign agreements to drive oil and gas pipelines, energy corridors, and repeal investment blocking federal policies

-

Alberta2 days ago

Alberta2 days agoCOWBOY UP! Pierre Poilievre Promises to Fight for Oil and Gas, a Stronger Military and the Interests of Western Canada

-

Crime1 day ago

Crime1 day ago“This is a total fucking disaster”