Energy

Canada badly misjudged the future of LNG

Canada’s failure to push more strongly for LNG has put us in a weaker position, but there is time to recover

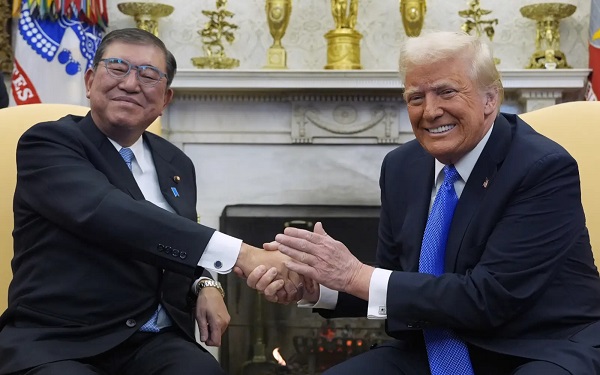

Earlier this month, President Donald Trump and Japanese Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba announced a joint American-Japanese venture for the Alaska LNG Project. Once built, the $44 billion project will ship gas from northern Alaska through an 800-mile pipeline to a liquefaction facility in Nikiski for export.

It is another sign that Canada needs to step up its LNG industry.

For years, Canada has been indecisive about liquefied natural gas (LNG), while others seized the moment. Now, with global demand for LNG surging and allies like Germany, Poland, and Japan needing stable energy sources, Canada finds itself left behind, and forced to regret regulatory missteps, political foot-dragging, and underestimating LNG’s long-term value.

The warning signs have been there for years. In 2022, as Europe scrambled to replace Russian gas after the invasion of Ukraine, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz personally came to Canada to request LNG exports. Instead of seizing the moment, only to be told there was no “strong business case” for Canadian LNG exports to Europe.

The same story followed with Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida in 2023 and Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis and Polish President Andrzej Duda in 2024. Each time, Canada’s response was the same, with no commitment, no plan, and no urgency.

Meanwhile, others acted. The U.S. and Qatar ramped up their LNG exports, locking in long-term contracts with European and Asian buyers. Germany, despite its push for renewables, invested in floating LNG terminals, recognizing that natural gas would be essential for energy security. Canada, despite having some of the world’s largest natural gas reserves, failed to position itself as a global supplier.

Canada’s failure isn’t just about hesitation, it’s about active obstruction. The federal government’s Bill C-69, the so-called “no more pipelines” law, created an onerous and unpredictable regulatory process for major energy projects. The CleanBC plan made it clear that investment in the sector would face endless hurdles.

The results have been severe. Since 2015, Canada has seen $670 billion in cancelled resource projects, including multiple LNG terminals on the Atlantic and Pacific coasts. The Energy East pipeline, which could have supplied LNG facilities in New Brunswick and enabled exports to Europe, was cancelled due to regulatory delays. The proposed expansion of Repsol’s LNG terminal in Saint John faced the same fate. Investors, spooked by uncertainty and government hostility, took their money elsewhere.

While Canada dithered, the world moved. As Stewart Muir, CEO of Resource Works, has written, LNG is not just a “bridge fuel”, it’s a destination fuel for much of the world. Despite heavy investment in renewables, countries like China are building coal-fired power plants because they lack secure, low-emissions alternatives.

If Canada had been exporting LNG between 2020 and 2022, it could have displaced an entire year’s worth of Canada’s domestic emissions in coal-dependent countries. Instead, Canada chose climate protectionism, prioritizing domestic emissions cuts over global impact.

The irony is that Canada’s hesitation to embrace LNG has hurt the climate more than it has helped. As coal consumption rises in Asia and Europe, emissions continue to soar, emissions that Canadian LNG could have displaced. A National Bank of Canada report found that transitioning India from coal to natural gas could cut four times more emissions than Canada’s total annual output, a massive missed opportunity.

Beyond environmental costs, the economic consequences are enormous. LNG projects in B.C. have been job engines, revitalizing communities once dependent on fishing, mining, and forestry. The Atlantic provinces, struggling economically, could have experienced the same boom had LNG infrastructure been developed there. Instead, they’ve been left behind.

There’s still time for Canada to change course, but it will require a complete reversal of policy. The federal government must:

- Reform permitting and regulatory processes to make LNG projects viable and competitive.

- Acknowledge LNG’s role in global emissions reduction and align climate policies with global realities.

- Develop Atlantic LNG infrastructure to serve European markets, capitalizing on growing demand.

As Enbridge CEO Greg Ebel said at LNG2023, Canada’s allies have been “knocking on our door…to which we’ve said…no.” It’s time to stop saying no, to LNG, to economic growth, and to a cleaner energy future. If we don’t act now, we’ll be left behind forever.

Alberta

Enbridge CEO says ‘there’s a good reason’ for Alberta to champion new oil pipeline

Enbridge CEO Greg Ebel. The company’s extensive pipeline network transports about 30 per cent of the oil produced in North America and nearly 20 per cent of the natural gas consumed in the United States. Photo courtesy Enbridge

From the Canadian Energy Centre

B.C. tanker ban an example of federal rules that have to change

The CEO of North America’s largest pipeline operator says Alberta’s move to champion a new oil pipeline to B.C.’s north coast makes sense.

“There’s a good reason the Alberta government has become proponent of a pipeline to the north coast of B.C.,” Enbridge CEO Greg Ebel told the Empire Club of Canada in Toronto the day after Alberta’s announcement.

“The previous [federal] government’s tanker ban effectively makes that export pipeline illegal. No company would build a pipeline to nowhere.”

It’s a big lost opportunity. With short shipping times to Asia, where oil demand is growing, ports on B.C.’s north coast offer a strong business case for Canadian exports. But only if tankers are allowed.

A new pipeline could generate economic benefits across Canada and, under Alberta’s plan, drive economic reconciliation with Indigenous communities.

Ebel said the tanker ban is an example of how policies have to change to allow Canada to maximize its economic potential.

Repealing the legislation is at the top of the list of needed changes Ebel and 94 other energy CEOs sent in a letter to Prime Minister Mark Carney in mid-September.

The federal government’s commitment to the tanker ban under former Prime Minister Justin Trudeau was a key factor in the cancellation of Enbridge’s Northern Gateway pipeline.

That project was originally targeted to go into service around 2016, with capacity to ship 525,000 barrels per day of Canadian oil to Asia.

“We have tried to build nation-building pipelines, and we have the scars to prove it. Five hundred million scars, to be quite honest,” Ebel said, referencing investment the company and its shareholders made advancing the project.

“Those are pensioners and retail investors and employees that took on that risk, and it was difficult,” he said.

For an industry proponent to step up to lead a new Canadian oil export pipeline, it would likely require “overwhelming government support and regulatory overhaul,” BMO Capital Markets said earlier this year.

Energy companies want to build in Canada, Ebel said.

“The energy sector is ready to invest, ready to partner, partner with Indigenous nations and deliver for the country,” he said.

“None of us is calling for weaker environmental oversight. Instead, we are urging government to adopt smarter, clearer, faster processes so that we can attract investment, take risks and build for tomorrow.”

This is the time for Canadians “to remind ourselves we should be the best at this,” Ebel said.

“We should lead the way and show the world how it’s done: wisely, responsibly, efficiently and effectively.”

With input from a technical advisory group that includes pipeline leaders and Indigenous relations experts, Alberta will undertake pre-feasibility work to identify the pipeline’s potential route and size, estimate costs, and begin early Indigenous engagement and partnership efforts.

The province aims to submit an application to the Federal Major Projects Office by spring 2026.

Alberta

The Technical Pitfalls and Political Perils of “Decarbonized” Oil

By Ron Wallace

The term “decarbonized oil” is popping up more and more in discussions of Canada’s energy politics. The concept refers to capturing and storing carbon dioxide (CO₂) generated during oil production and processing, thereby reducing greenhouse gas emissions, in order to support the continued strength of Canada’s oil and natural sector, the nation’s number-one export earner and crucial to the economies of Alberta and Saskatchewan. Projects like the Weyburn Carbon Capture, Utilization and Sequestration Project in Saskatchewan have demonstrated the idea’s technical feasibility by sequestering 1.7 million tonnes of CO₂ annually while producing incremental oil.

The key question now is whether this type of process can be dramatically scaled up – by anywhere from six to over 20 times – to facilitate what Alberta Premier Danielle Smith has termed a “grand bargain”: using carbon capture and storage (CCS) to gain a greenlight from the federal government for a new oil export line to the West Coast, enabling Alberta to continue growing oil production and generating jobs while advancing Ottawa’s climate goals. Prime Minister Mark Carney may be prone to hedging and ambiguity, but he has now made it clear that any such pipeline will indeed be contingent on Alberta proving it can “decarbonize” its oil

production.

The Pathways Alliance, a group of six producers representing 95% of Canada’s oil sands production, has designed a $16.5 billion CCS network to capture and store CO₂ from up to 20 facilities, aiming for 11 million tonnes per year in Phase 1 and a breathtaking 40 million tonnes in Phase 2. Pathways is intended to help build consensus in favour of a new oil export pipeline that could enable up to 25% growth in Alberta’s oil production – generating possibly $20 billion per year in export revenues.

While credible critics, including the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA) and energy economist Jennifer Considine, highlight the high costs, uncertain revenues and poor returns from several other attempts at large-scale CCS, Alberta’s UCP government appears to view it as the way out of its current impasse with Ottawa. It believes the profits generated from exports of Alberta’s decarbonized oil could themselves help finance the CCS facilities required for the “grand bargain” to be sealed.

Smith has been keeping up the political pressure, recently announcing that Alberta will fund and lead the effort to submit a formal pipeline application to the Carney government’s new Major Projects Office. Major obstacles remain, but none is more serious than Carney maintaining predecessor Justin Trudeau’s suite of anti-energy policies, particularly the draft oil and natural gas emissions cap, as part of his government’s intention to meet net-zero targets by 2050 (although Carney has recently indicated some flexibility in this view). Smith argues that this is effectively an “unconstitutional” production cap that threatens Alberta’s economic future, vowing to challenge it legally if Carney doesn’t shelve it.

Smith’s government at the same time is pursuing a more conciliatory tactic, offering to help advance federal climate objectives through CCS in order to speed up pipeline approvals under Carney’s Bill C-5. In this track, there is a question as to whether Alberta may be walking into an economic and technological trap that it will regret.

That is because the “grand bargain” would create two different classes of oil in Canada, operating under different sets of regulations and resulting in different cost structures. Western Canada’s crude oil producers would shoulder costly and technically challenging decarbonization requirements – plus the threat of federal veto over any new oil projects that weren’t similarly “decarbonized”. Canadian-produced oil would enter international export markets at a significant if not ruinous competitive disadvantage, risking not only profitability but market share. Eastern Canada’s oil refiners, meanwhile, would remain free to import fully “carbonized”

oil at the lowest prices they could get from countries with significantly looser environmental standards.

The Alberta oil sands currently generate 58% of Canada’s total oil output. Data from December 2023 shows Alberta producing a record 4.53 million barrels per day as major oil export pipelines including Trans Mountain, Keystone and the Enbridge Mainline operated at near capacity. The same year, Eastern Canada imported on average about 490,000 barrels per day by pipeline and sea from the United States (72.4%), Nigeria (12.9%) and Saudi Arabia (10.7%). Since 1988, imports by marine terminals along the St. Lawrence River have exceeded $228 billion, while imports by New Brunswick’s Irving Oil Ltd. refinery totalled $136 billion from 1988 to 2020.

The economic viability of large-scale CCS projects remains completely unproven; indeed, attempts to date in other jurisdictions have performed poorly. Attempting to “decarbonize” Alberta’s oil, then, makes little economic sense; it appears to be based more on the Carney government’s ideological objectives set to achieve global climate objectives.

The question thus becomes why Alberta is agreeing to a policy that could trap its taxpayers in a hugely expensive and unfair system that could imperil consideration of any new pipelines for Canadian oil exports, especially when private capital already largely remains on the sidelines.

Not only Albertans but Canadians generally need to carefully reconsider any “grand bargain” that hinges on “decarbonization” of western Canadian oil, because doing so threatens the economic viability of Alberta oil production and associated export pipelines – without meaningfully reducing global CO 2 emissions. And if industry proves unable to raise the vast capital required to construct the CCS projects, while lacking the cash flow to cover the steep ongoing costs needed to operate them, then where is the money to come from? At a time when Canada’s fiscal trajectory is so worrisome, the shortfall had better not be made up through public subsidies.

Even worse than the yawning fiscal risks, such an approach risks splitting the country into two economic zones: a West burdened by costly decarbonization requirements making Alberta’s oil some of the world’s least profitable to produce, and an East benefiting as before from cheaper imported oil. This is hardly conducive to national unity. It is time for Alberta to reconsider the “grand bargain”.

The original, full-length version of this article was recently published in C2C Journal.

Ron Wallace is a former Member of the National Energy Board.

-

Alberta2 days ago

Alberta2 days agoFact, fiction, and the pipeline that’s paying Canada’s rent

-

Energy1 day ago

Energy1 day agoIndigenous Communities Support Pipelines, Why No One Talks About That

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoFinance Titans May Have Found Trojan Horse For ‘Climate Mandates’

-

International2 days ago

International2 days agoSigned and sealed: Peace in the Middle East

-

Alberta1 day ago

Alberta1 day agoOil Sands are the Costco of world energy – dependable and you know exactly where to find it

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoFinance Committee Recommendation To Revoke Charitable Status For Religion Short Sighted And Destructive

-

International1 day ago

International1 day agoNumber of young people identifying as ‘transgender’ declines sharply: report

-

Alberta1 day ago

Alberta1 day agoThe Technical Pitfalls and Political Perils of “Decarbonized” Oil