Break The Needle

B.C. crime survey reveals distrust in justice system, regional divides

By Alexandra Keeler

In late August, the RCMP seized nearly 40 kilograms of illegal drugs and half-a-million dollars in cash from a home in Prince George, B.C., while responding to a break-and-enter call.

The RCMP linked the drug operation to organized crime and said it was one of the largest busts in the history of the 80,000-person city, which is located in the B.C. heartland.

“It is obvious we can no longer ignore the effects of the B.C. gang conflict in Prince George, as this is a clear indication that more than our local drug traffickers are using Prince George as a base of operations,” Insp. Darin Rappel, interim detachment commander for the Prince George RCMP, told local media at the time.

It is operations such as these that may be contributing to a perception among British Columbians — particularly those in northern parts of the province — that crime rates are rising.

A survey released Sept. 24 shows a majority of respondents believe B.C. crime rates are up — and often unreported — even though official crime data suggest the opposite.

The survey was commissioned by Save Our Streets, a coalition of more than 100 B.C. community and business groups that is calling for non-partisan, province-wide efforts to establish safer communities in the face of widespread mental health and addiction issues and lack of confidence in the justice system.

“I’m glad that we have our data,” said Jess Ketchum, co-founder of Save Our Streets. “[N]ow we can show that, ‘Look, 88 per cent of the public in B.C. believe that crime is going unreported.’”

“[And] the reason that it’s going unreported is that they’ve lost faith in the justice system,” he said.

‘Revolving doors’

Fifty-five per cent of the 1,200 British Columbians who participated in the survey said they believed criminal activity had increased over the past four years. The survey did not specify types of crime, though it mentioned concerns about violence against employees, vandalism and theft.

But crime data tells a different story. B.C. crime rates fell eight per cent during the years 2020 to 2023, according to Statistics Canada.

Underreporting of crime may partly explain the trend. A 2019 nationwide Statistics Canada survey of individuals aged 15 years and older showed only 29 per cent of violent and non-violent incidents were reported to police. Victims often cited the crime being minor, not important, or no one being harmed as reasons for not reporting.

What is clear is many British Columbians perceive crime is being underreported: 88 per cent of all survey respondents said they believe many crimes go unreported.

|

Perceptions of Crime & Public Safety in British Columbia. Online survey commissioned by Save Our Streets, conducted by Research Co. with a representative sample of 1,200 British Columbians, Sept 9-12, 2024. (Graphic: Alexandra Keeler)

Mario Canseco, president of Research Co., the public research company that conducted the Save Our Streets survey, attributes the gap between actual and perceived crime rates to the heightened visibility of mental health and addiction issues in the media.

“You look at the reports, you watch television news, listen to the radio, or read the newspaper, and you see that something happened, or that there was a high-profile attack,” said Canseco. “That leads people to believe that things are going badly.”

Survey respondents, though, attributed the lack of crime reporting to a lack of confidence in the justice system, with 75 per cent saying they believe an inadequate court system is to blame. Eighty-seven per cent said they supported bail reform to keep repeat offenders in custody while awaiting trial.

“There was support [in the survey results] for judicial reform that would allow for steps to resolve the revolving doors of the justice system when it comes to repeat offenders,” said Ketchum.

Cowboys

The survey highlighted regional differences in perceptions of B.C. crime rates and views on whether addiction-related crime ought to be addressed as a public health or law enforcement issue.

Respondents from Northern B.C., Prince George and the surrounding Cariboo region were more likely to say they believed criminal activity had increased than respondents from southern and coastal regions of the province.

Canseco suggests that drug use and associated crime are now becoming more apparent in smaller communities, as the drug crisis has spread beyond the major cities of Vancouver and Victoria. Residents of these communities may thus see these problems as more novel and alarming, he says.

Eighty-four per cent of respondents in Northern B.C. said they viewed opioid addiction as a health issue, while only 68 per cent of respondents in Prince George/Cariboo shared this perspective.

Respondents from Prince George/Cariboo exhibited the strongest preference for punitive measures regarding addiction and mental health, with nearly unanimous support for harsher penalties, bail reform and increased police presence.

“It’s one of the tougher areas in the province … somewhat more cowboys,” Ketchum said about Prince George and the Cariboo region, where his hometown of Quesnel is located. “I think there’s less tolerance.”

Subscribe for free to get BTN’s latest news and analysis, or donate to our journalism fund.

Differences in each region’s demographic makeup may also help to explain differing sentiments.

Northern B.C. has the highest concentration of B.C.’s Indigenous population, with about 17 per cent of the population identifying as Indigenous, versus eight per cent in Prince George.

Indigenous communities tend to emphasize addiction as a health issue rooted in historical trauma and social inequities, and prefer community-based healing over punitive measures. Indigenous communities are also frequently distrustful of the RCMP, given its history of being used to extend colonial control.

A majority of all survey respondents favoured investing in mental health facilities, drug education campaigns and rehabilitation over harm-reduction strategies such as safer supply programs, supervised injection sites and drug decriminalization.

“People want to see a more holistic approach [to the drug crisis],” said Canseco. “[T]he voter who hasn’t been exposed to something like [harm reduction], and who may be reacting to what they see on social media, is having a harder time understanding whether this is actually going to help.”

“I was pleased to see the level of support for more investments in recovery, more investments in treatment, around the province,” said Ketchum.

But Ketchum says the preference of some respondents for punitive approaches to B.C. crime rates – particularly in the province’s more northern regions — worries him.

“I believe that if governments don’t respond adequately now, and this is allowed to escalate, that there’ll be more and more instances of people taking these things into their own hands.”

This article was produced through the Breaking Needles Fellowship Program, which provided a grant to Canadian Affairs, a digital media outlet, to fund journalism exploring addiction and crime in Canada. Articles produced through the Fellowship are co-published by Break The Needle and Canadian Affairs.

Subscribe to Break The Needle. Our content is always free – but if you want to help us commission more high-quality journalism, consider getting a voluntary paid subscription.

Addictions

‘Over and over until they die’: Drug crisis pushes first responders to the brink

First responders say it is not overdoses that leave them feeling burned out—it is the endless cycle of calls they cannot meaningfully resolve

The soap bottle just missed his head.

Standing in the doorway of a cluttered Halifax apartment, Derek, a primary care paramedic, watched it smash against the wall.

Derek was there because the woman who threw it had called 911 again — she did so nearly every day. She said she had chest pain. But when she saw the green patch on his uniform, she erupted. Green meant he could not give her what she wanted: fentanyl.

She screamed at him to call “the red tags” — advanced care paramedics authorized to administer opioids. With none available, Derek declared the scene unsafe and left. Later that night, she called again. This time, a red-patched unit was available. She got her dose.

Derek says he was not angry at the woman, but at the system that left her trapped in addiction — and him powerless to help.

First responders across Canada say it is not overdoses that leave them feeling burned out — it is the endless cycle of calls they cannot meaningfully resolve. Understaffed, overburdened and dispatched into crises they are not equipped to fix, many feel morally and emotionally drained.

“We’re sending our first responders to try and manage what should otherwise be dealt with at structural and systemic levels,” said Nicholas Carleton, a University of Regina researcher who studies the mental health of public safety personnel.

Canadian Affairs agreed to use pseudonyms for the two frontline workers referenced in this story. Canadian Affairs also spoke with nine other first responders who agreed to speak only on background. All of these sources cited concerns about workplace retaliation for speaking out.

Moral injury

Canada’s opioid crisis is pushing frontline workers such as paramedics to the brink.

A 2024 study of 350 Quebec paramedics shows one in three have seriously considered suicide. Globally, ambulance workers have among the highest suicide rates of public service personnel.

Between 2017 and 2024, Canadian paramedics responded to nearly 240,000 suspected opioid overdoses. More than 50,000 of those were fatal.

Yet many paramedics say overdose calls are not the hardest part of the job.

“When they do come up, they’re pretty easy calls,” said Derek. Naloxone, a drug that reverses overdoses, is readily available. “I can actually fix the problem,” he said. “[It’s a] bit of instant gratification, honestly.”

What drains him are the calls they cannot fix: mental health crises, child neglect and abuse, homelessness.

“The ER has a [cardiac catheterization] lab that can do surgery in minutes to fix a heart attack. But there’s nowhere I can bring the mental health patients.

“So they call. And they call. And they call.”

Thomas, a primary care paramedic in Eastern Ontario, echoes that frustration.

“The ER isn’t a good place to treat addiction,” he said. “They need intensive, long-term psychological inpatient treatment and a healthy environment and support system — first responders cannot offer that.”

That powerlessness erodes trust. Paramedics say patients with addictions often become aggressive, or stop seeking help altogether.

“We have a terrible relationship with the people in our community struggling with addiction,” Thomas said. “They know they will sit in an ER bed for a few hours while being in withdrawals and then be discharged with a waitlist or no follow-up.”

Carleton, of the University of Regina, says that reviving people repeatedly without improvement decreases morale.

“You’re resuscitating someone time and time again,” said Carleton, who is also director of the Psychological Trauma and Stress Systems Lab, a federal unit dedicated to mental health research for public safety personnel. “That can lead to compassion fatigue … and moral injury.”

Katy Kamkar, a clinical psychologist focused on first responder mental health, says moral injury arises when workers are trapped in ethically impossible situations — saving a life while knowing that person will be back in the same state tomorrow.

“Burnout is … emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal accomplishment,” she said in an emailed statement. “High call volumes, lack of support or follow-up care for patients, and/or bureaucratic constraints … can increase the risk of reduced empathy, absenteeism and increased turnover.”

Kamkar says moral injury affects all branches of public safety, not just paramedics. Firefighters, who are often the first to arrive on the scene, face trauma from overdose deaths. Police report distress enforcing laws that criminalize suffering.

Understaffed and overburdened

Staffing shortages are another major stressor.

“First responders were amazing during the pandemic, but it also caused a lot of fatigue, and a lot of people left our business because of stress and violence,” said Marc-André Périard, vice president of the Paramedic Chiefs of Canada.

Nearly half of emergency medical services workers experience daily “Code Blacks,” where there are no ambulances available. Vacancy rates are climbing across emergency services. The federal government predicts paramedic shortages will persist over the coming decade, alongside moderate shortages of police and firefighters.

Unsafe work conditions are another concern. Responders enter chaotic scenes where bystanders — often fellow drug users — mistake them for police. Paramedics can face hostility from patients they just saved, says Périard.

“People are upset that they’ve been taken out of their high [when Naloxone is administered] and not realizing how close to dying they were,” he said.

Thomas says safety is undermined by vague, inconsistently enforced policies. And efforts to collect meaningful data can be hampered by a work culture that punishes reporting workplace dangers.

“If you report violence, it can come back to haunt you in performance reviews” he said.

Some hesitate to wait for police before entering volatile scenes, fearing delayed response times.

“[What] would help mitigate violence is to have management support their staff directly in … waiting for police before arriving at the scene, support paramedics in leaving an unsafe scene … and for police and the Crown to pursue cases of violence against health-care workers,” Thomas said.

“Right now, the onus is on us … [but once you enter], leaving a scene is considered patient abandonment,” he said.

Upstream solutions

Carleton says paramedics’ ability to refer patients to addiction and mental health referral networks varies widely based on their location. These networks rely on inconsistent local staffing, creating a patchwork system where people easily fall through the cracks.

“[Any] referral system butts up really quickly against the challenges our health-care system is facing,” he said. “Those infrastructures simply don’t exist at the size and scale that we need.”

Périard agrees. “There’s a lot of investment in safe injection sites, but not as much [resources] put into help[ing] these people deal with their addictions,” he said.

Until that changes, the cycle will continue.

On May 8, Alberta renewed a $1.5 million grant to support first responders’ mental health. Carleton welcomes the funding, but says it risks being futile without also addressing understaffing, excessive workloads and unsafe conditions.

“I applaud Alberta’s investment. But there need to be guardrails and protections in place, because some programs should be quickly dismissed as ineffective — but they aren’t always,” he said.

Carleton’s research found that fewer than 10 mental health programs marketed to Canadian governments — out of 300 in total — are backed up by evidence showing their effectiveness.

In his view, the answer is not complicated — but enormous.

“We’ve got to get way further upstream,” he said.

“We’re rapidly approaching more and more crisis-level challenges… with fewer and fewer [first responders], and we’re asking them to do more and more.”

This article was produced through the Breaking Needles Fellowship Program, which provided a grant to Canadian Affairs, a digital media outlet, to fund journalism exploring addiction and crime in Canada. Articles produced through the Fellowship are co-published by Break The Needle and Canadian Affairs.

Break The Needle

B.C. doubles down on involuntary care despite underinvestment

By Alexandra Keeler

B.C.’s push to replace coercive care with community models never took hold — and experts say province isn’t fixing that problem

Two decades ago, B.C. closed one of the last large mental institutions in the province. The institution, known as Riverview Hospital in Coquitlam, had at its peak housed nearly 5,000 patients across a sprawling campus.

There, patients with mental illnesses were subjected to a range of inhumane treatments, city records show. These included coma therapy, induced seizures, lobotomies and electroshock therapy.

When the province transferred patients out of institutions like Riverview during the 1990s and early 2000s, it promised them access to community-based mental health care instead. But that system never materialized.

“There was not a sustained commitment to seeing [the deinstitutionalization process] through,” said Julian Somers, a professor at Simon Fraser University who specializes in mental health, addiction and homelessness.

“[B.C.] did not put forward a clear vision of what we were trying to achieve and how we were going to get there. So we languished.”

Today, amid a sharp rise in involuntary hospitalizations, experts say B.C. risks repeating the mistakes of the past. The province is using coercive forms of care to treat individuals with mental health and substance use disorders, while failing to build community supports.

“We’re essentially doing the same thing we did with institutions,” said Somers, who began his clinical career at Riverview Hospital in the 1980s.

“[We’re] creating a system that doesn’t actually help people and may make things worse.”

Riverview’s legacy

B.C.’s push for deinstitutionalization was driven by growing evidence that large psychiatric institutions were harmful, and that community-based care was more humane and cost effective.

Nationally, advances in antipsychotic medication, rising civil rights concerns and growing financial pressures were also spurring a shift away from institutional care.

A 2006 Senate report showed community care could match institutional care in both effectiveness and cost — provided it was properly funded.

“There was sufficient evidence demonstrating that people with severe mental illness had better outcomes in community settings,” said Somers.

Somers says people who stay long term in institutions can develop “institutionalization syndrome,” characterized by increased dependency, worse mental health outcomes and greater social decline.

At the time, B.C. was restructuring its health system, promising to replace institutions like Riverview with a regional network of mental health services.

The problem was, that network never fully materialized.

Marina Morrow, a professor at York University’s School of Health Policy and Management who tracked B.C.’s deinstitutionalization process, says the province placed patients in alternative care. But these providers were not always well-equipped to manage psychiatric patients.

“Nobody left Riverview directly to the street,” Morrow said. “But some … might have ended up being homeless over time.”

A 2012 study led by Morrow found that older psychiatric Riverview patients who were relocated to remote regional facilities strained overburdened and ill-equipped staff, leading to poor patient outcomes.

Somers says B.C. abandoned its vision of a robust, community-based system.

“We allowed BC Housing to have responsibility for mental health and addiction housing,” he said. “And no one explained to BC Housing how they ought to best fulfill that responsibility.”

Somers says the province’s reliance on group housing was part of the problem. Group housing isolates residents from broader society, instead of integrating them into a community. A 2013 study by Somers shows people tend to have better outcomes if they get to live in “scattered-site housing,” where tenants live in diverse neighbourhoods while still receiving personalized support.

“All of us … are influenced substantially by where we live, what we do, and who we do things with,” he said.

Somers says a greater investment in community care would have emphasized better housing, nutrition, education, work and social connection. “Those are all way more important than medical care in terms of the health of the population,” he said.

“We closed institutions having no [alternative] functioning model.”

Reinstitutionalization

Despite B.C.’s efforts to deinstitutionalize, the practice of institutionalizing certain patients never truly went away.

“We institutionalize way more people now than we ever did, even at peak Riverview population,” said Laura Johnston, legal director at Health Justice, a B.C. non-profit focused on coercive health laws.

Between 2008 and 2018, involuntary hospitalizations rose nearly 66 per cent, while voluntary admissions remained flat.

In the 2023-24 fiscal year, more than 25,000 individuals were involuntarily hospitalized at acute care facilities, down only slightly from 26,600 the previous year, according to B.C.’s health ministry. These admissions involved about 18,000 unique patients, indicating many individuals were detained more than once.

Subscribe for free to get Break The Needle’s latest news and analysis – or donate to our investigative journalism fund.

In September 2024, a string of high-profile attacks in Vancouver by individuals with histories of mental illness reignited public calls to reopen Riverview Hospital.

That month, B.C. Premier David Eby pledged to further expand involuntary care. Currently, B.C. has 75 designated facilities that can hold individuals admitted under the Mental Health Act. The act permits individuals to be involuntarily detained if they have a mental disorder requiring treatment and are significantly impaired. These existing facilities host about 2,000 beds for involuntary patients.

Eby’s pledge was to add another 400 hospital-based mental health beds, and two new secure care facilities within correctional facilities.

Johnston, of Health Justice, says Eby’s announcement merely continues the same flawed approach. It “[ties] access to services with detention and an involuntary care approach, rather than investing in the voluntary, community-based services that we’re so sorely lacking in B.C.”

Kathryn Embacher, provincial executive director of adult mental health and substance use with BC Mental Health & Substance Use Services, says additional resources are needed to support those with complex needs.

“We continue to work with the provincial government to increase the services we are providing,” Embacher said. “Having enough resources to serve the most seriously ill clients is important to provide access to all clients.”

|

θəqiʔ ɫəwʔənəq leləm’ (the Red Fish Healing Centre for Mental Health and Addiction) is for clients with complex and concurrent mental health and substance use disorders. | BC Mental Health and Substance Use Services website

Inertia

If B.C. wants to avoid repeating the mistakes of its past, it needs to change its approach, sources say.

One concern Johnston has is with Section 32 of the Mental Health Act. Largely unchanged since 1964, it grants broad powers to medical professionals to detain and control patients.

“It grants unchecked authority,” she said.

Data obtained by Health Justice show one in four involuntarily detained patients in B.C. is subjected to seclusion or restraint. And even this figure may understate the problem. B.C. only began reliably tracking its seclusion and restraint practices in 2020, and only collects data on the first three days of detention.

A B.C. health ministry spokesperson told Canadian Affairs that involuntary care is sometimes necessary when individuals in crisis pose a risk to themselves or others.

“It’s in these situations where a patient, who meets very specific criteria, may need to be held involuntarily under the Mental Health Act,” the spokesperson said.

But York University professor Morrow says those “specific criteria” are applied far too broadly. “We have this huge hammer [involuntary care] that sees everything as a nail,” she said. “Involuntary treatment was meant for rare, extreme cases. But that’s not how it’s being used today.”

Morrow advocates for reviving interdisciplinary care that brings psychiatry, psychology and primary care together in community-based settings. She pointed to several promising models, including Toronto’s Gerstein Crisis Centre, which provides community-based crisis services for those with mental health and substance use issues.

Somers sees Alberta’s recovery-oriented model as a potential blueprint. This model prioritizes live-in recovery communities that combine therapeutic support with job training and stable housing, and which permit residents to stay up to one year. Alberta has committed to building 11 such communities across the province.

“They provide people with respite,” Somers said.

“They provide them with the opportunity to practice and gain confidence, waking up each day, going through each day without drugs, seeing other people do it, gaining confidence that they themselves can do it.”

Johnston advocates for safeguards on involuntary treatment.

“There’s nothing in our laws that compels the health system to ensure that they’re offering community-based or voluntary based services wherever possible, and that they are not using involuntary care approaches without exhausting other options,” she said.

“There’s inertia in a system that’s operated this way for so long.”

This article was produced through the Breaking Needles Fellowship Program, which provided a grant to Canadian Affairs, a digital media outlet, to fund journalism exploring addiction and crime in Canada. Articles produced through the Fellowship are co-published by Break The Needle and Canadian Affairs.

Subscribe to Break The Needle.

Our content is always free – but if you want to help us commission more high-quality journalism,

consider getting a voluntary paid subscription.

-

Indigenous2 days ago

Indigenous2 days agoInternal emails show Canadian gov’t doubted ‘mass graves’ narrative but went along with it

-

Bruce Dowbiggin2 days ago

Bruce Dowbiggin2 days agoEau Canada! Join Us In An Inclusive New National Anthem

-

Crime2 days ago

Crime2 days agoEyebrows Raise as Karoline Leavitt Answers Tough Questions About Epstein

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoCarney’s new agenda faces old Canadian problems

-

Alberta2 days ago

Alberta2 days agoCOWBOY UP! Pierre Poilievre Promises to Fight for Oil and Gas, a Stronger Military and the Interests of Western Canada

-

Alberta2 days ago

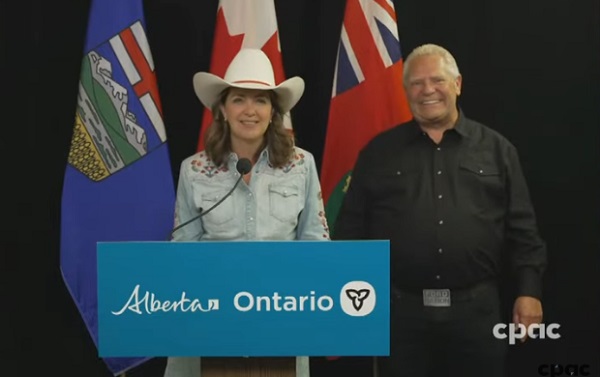

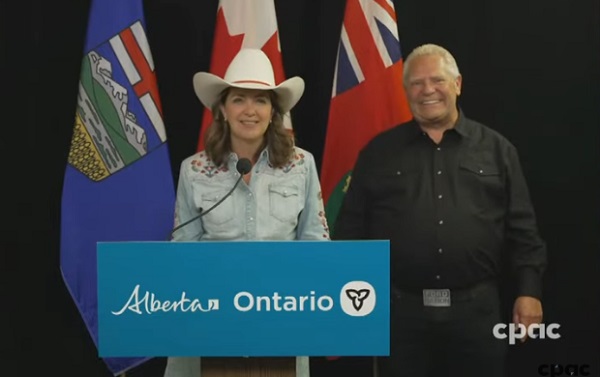

Alberta2 days agoAlberta and Ontario sign agreements to drive oil and gas pipelines, energy corridors, and repeal investment blocking federal policies

-

Crime1 day ago

Crime1 day ago“This is a total fucking disaster”

-

International2 days ago

International2 days agoChicago suburb purchases childhood home of Pope Leo XIV