Christopher Rufo

In Charleroi, Pennsylvania, the local population grapples with a surge of Haitian migrants.

Charleroi, Pennsylvania, is a deeply troubled place. The former steel town, built along a stretch of the Monongahela River, south of Pittsburgh, has experienced the typical Rust Belt rise and fall. The industrial economy, which had turned it into something resembling a company town, hollowed out after the Second World War. Some residents fled; others succumbed to vices. The steel mills disappeared. Two drug-abuse treatment centers have since opened their doors.

The town’s population had steadily declined since the middle of the twentieth century, with the most recent Census reporting slightly more than 4,000 residents. Then, suddenly, things changed. Local officials estimate that approximately 2,000 predominantly Haitian migrants have moved in. The town’s Belgium Club and Slovak Club are mostly quiet nowadays, while the Haitians and other recent immigrants have quickly established their presence, even dominance, in a dilapidated corridor downtown.

This change—the replacement of the old ethnics with the new ethnics—is an archetypal American story. And, as in the past, it has caused anxieties and, at times, conflict.

The municipal government has felt the strain. The town, already struggling with high rates of poverty and unemployment, has been forced to assimilate thousands of new arrivals. The schools now crowd with new Haitian pupils, and have had to hire translators and English teachers. Some of the old pipes downtown have started releasing the smell of sewage. And, according to a town councilman, there is a growing sense of trepidation about the alarming number of car crashes, with some vehicles reportedly slamming into buildings.

Among the city’s old guard, frustrations are starting to boil over. Instead of being used to revitalize these communities, these residents argue, resources get redirected to the new arrivals, who undercut wages, drive rents up, and, so far, have failed to assimilate. Worst of all, these residents say, they had no choice—there was never a vote on the question of migration; it simply materialized.

Former president Donald Trump, echoing the sentiments of some of Charleroi’s native citizens, has cast the change in a sinister light. As he told the crowd at a recent rally in Indiana, Pennsylvania, “it takes centuries to build the unique character of each state. . . . But reckless migration policy can change it quickly and permanently.” Progressives, as expected, countered with the usual arguments, claiming that Trump was stoking fear, inciting nativist resentment, and even putting the Haitian migrants in danger.

Neither side, however, seems to have grappled with the mechanics of Charleroi’s abrupt transformation. How did thousands of Haitians end up in a tiny borough in Western Pennsylvania? What are they doing there? And cui bono—who benefits?

The answers to these questions have ramifications not only for Charleroi, but for the general trajectory of mass migration under the Biden administration, which has allowed more than 7 million migrants to enter the United States, either illegally, or, as with some 309,000 Haitians, under ad hoc asylum rules.

The basic pattern in Charleroi has been replicated in thousands of cities and towns across America: the federal government has opened the borders to all comers; a web of publicly funded NGOs has facilitated the flow of migrants within the country; local industries have welcomed the arrival of cheap, pliant labor. And, under these enormous pressures, places like Charleroi often revert to an older form: that of the company town, in which an open conspiracy of government, charity, and industry reshapes the society to its advantage—whether the citizens want it or not.

The best way to understand the migrant crisis is to follow the flow of people, money, and power—in other words, to trace the supply chain of human migration. In Charleroi, we have mapped the web of institutions that have facilitated the flow of migrants from Port-au-Prince. Some of these institutions are public and, as such, must make their records available; others, to avoid scrutiny, keep a low profile.

The initial, and most powerful, institution is the federal government. Over the past four years, Customs and Border Patrol has reported hundreds of thousands of encounters with Haitian nationals. In addition, the White House has admitted 210,000 Haitians through its controversial Humanitarian Parole Program for Cubans, Haitians, Nicaraguans, and Venezuelans (CHNV), which it paused in early August and has since relaunched. The program is presented as a “lawful pathway,” but critics, such as vice presidential candidate J. D. Vance, have called it an “abuse of asylum laws” and warned of its destabilizing effects on communities across the country.

The next link in the web is the network of publicly funded NGOs that provide migrants with resources to assist in travel, housing, income, and work. These groups are called “national resettlement agencies,” and serve as the key middleman in the flow of migration. The scale of this effort is astounding. These agencies are affiliated with more than 340 local offices nationwide and have received some $5.5 billion in new awards since 2021. And, because they are technically non-governmental institutions, they are not required to disclose detailed information about their operations.

In Charleroi, one of the most active resettlement agencies is Jewish Family and Community Services Pittsburgh. According to a September Pittsburgh Post-Gazette report, JFCS staff have been traveling to Charleroi weekly for the past year and a half to resettle many of the migrants. The organization has offered to help migrants sign up for welfare programs, including SNAP, Medicaid, and direct financial assistance. While JFCS Pittsburgh offers “employment services“ to migrants, it denies any involvement with the employer and staffing agencies that were the focus of our investigation.

And yet, business is brisk. In 2023, JFCS Pittsburgh reported $12.5 million in revenue, of which $6.15 million came directly from government grants. Much of the remaining funding came from other nonprofits that also get federal funds, such as a $2.8 million grant from its parent organization, HIAS. And JFCS’s executives enjoy generous salaries: the CEO earned $215,590, the CFO $148,601, and the COO $125,218—all subsidized by the taxpayer.

What is next in the chain? Business. In Charleroi, the Haitians are, above all, a new supply of inexpensive labor. A network of staffing agencies and private companies has recruited the migrants to the city’s factories and assembly lines. While some recruitment happens through word-of-mouth, many staffing agencies partner with local nonprofits that specialize in refugee resettlement to find immigrants who need work.

At the center of this system in Charleroi is Fourth Street Foods, a frozen-food supplier with approximately 1,000 employees, most of whom work on the assembly line. In an exclusive interview, Chris Scott, the CEO and COO of Fourth Street Barbeque (the legal name of the firm that does business as Fourth Street Foods) explained that his company, like many factory businesses, has long relied on immigrant labor, which, he estimates, makes up about 70 percent of its workforce. The firm employs many temporary workers, and, with the arrival of the Haitians, has found a new group of laborers willing to work long days in an industrial freezer, starting at about $12 an hour.

Many of these workers are not directly employed by Fourth Street Foods. Instead, according to Scott, they are hired through staffing agencies, which pay workers about $12 an hour for entry-level food-processing roles and bill Fourth Street Foods over $16 per hour to cover their costs, including transportation and overhead. (The average wage for an entry-level food processor in Washington County was $16.42 per hour in 2023.)

According to a Haitian migrant who worked at Fourth Street and a review of video footage, three staffing agencies—Wellington Staffing Agency, Celebes Staffing Services, and Advantage Staffing Agency—are key conduits for labor in the city. None have websites, advertise their services, or appear in job listings. According to Scott, Fourth Street Foods relies on agencies to staff its contract workforce, but he declined to specify which agencies, citing nondisclosure agreements.

The final link is housing. And here, too, Fourth Street Foods has an organized interest. During the Covid-19 pandemic, Scott said, Fourth Street Foods was “scrambling” to find additional workers. The owner of the company, David Barbe, stepped in, acquiring and renovating a “significant number of homes” to provide housing for his workforce. A property search for David Barbe and his other business, DB Rentals LLC, shows records of more than 50 properties, many of which are concentrated on the same streets.

After the initial purchases, Barbe required some of the existing residents to vacate to make room for newcomers. A single father, who spoke on condition of anonymity, was forced to leave his home after it was sold to DB Rentals LLC in 2021. “[W]e had to move out [on] very short notice after five years of living there and being great tenants,” he explained. Afterward, a neighbor informed him that a dozen people of Asian descent had been crammed into the two-bedroom home. They were “getting picked up and dropped off in vans.”

“My kids were super upset because that was the house they grew up in since they were little,” the man said. “It was just all a huge nightmare.”

In recent years, a debate has raged about “replacement migration,” which some left-wing critics have dubbed a racist conspiracy theory. But in Charleroi, “replacement” is a plain reality. While the demographic statistics have shifted dramatically in recent years, replacement happens in more prosaic ways, too: a resident moves away. Another arrives. The keys to a rental apartment change hands.

In one sense, this is unremarkable. Since the beginning, America has been the land of migration, replacement, and change. The original Belgian settlers of Charleroi were replaced by the later-arriving Slavic populations, who are now, in turn, being replaced by men and women from Port-au-Prince. The economy changed along the same lines. The steel plants shut down years ago. The glass factory, the last remaining symbol of the Belgian glass-makers, might suspend operations soon. The largest employer now produces frozen meals.

In another sense, however, legitimate criticisms can be made of what is happening in Charleroi. First, the benefits of mass migration seem to accrue to the organized interests, while citizens and taxpayers absorb the costs. No doubt, the situation is advantageous to David Barbe of Fourth Street Foods, who can pay $16 an hour to the agencies that employ his contract labor force, then recapture some of those wages in rent—just like the company towns from a century ago.

But for the old residents of Charleroi, who cherish their distinct heritage and fear that their quality of life is being compromised, it’s mostly downside. The evictions, the undercut wages, the car crashes, the cramped quarters, the unfamiliar culture: these are not trivialities, nor are they racist conspiracy theories. They are the signs of a disconcerting reality: Charleroi is a dying town that could not revitalize itself on its own, which made it the perfect target for “revitalization” by elite powers—the federal government, the NGOs, and their local satraps.

The key question in Charleroi is the fundamental question of politics: Who decides? The citizens of the United States, and of Charleroi, have been assured since birth that they are the ultimate sovereign. The government, they were told, must earn the consent of the governed. But the people of Charleroi were never asked if they wanted to submit their borough to an experiment in mass migration. Others chose for them—and slandered them when they objected.

The decisive factor, which many on the institutional Left would rather conceal, is one of power. Martha’s Vineyard, when faced with a single planeload of migrants, can evict them in a flash. But Charleroi—the broken man of the Rust Belt—cannot. This is the reality of replacement: the strong do what they can, and the weak endure what they must.

Christopher Rufo is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Business

Washington Got the Better of Elon Musk

The tech tycoon’s Department of Government Efficiency was prevented from achieving its full reform agenda.

It seems that the postmodern world is a conspiracy against great men. Bureaucracy now favors the firm over the founder, and the culture views those who accumulate too much power with suspicion. The twentieth century taught us to fear such men rather than admire them.

Elon Musk—who has revolutionized payments, automobiles, robotics, rockets, communications, and artificial intelligence—may be the closest thing we have to a “great man” today. He is the nearest analogue to the robber barons of the last century or the space barons of science fiction. Yet even our most accomplished entrepreneur appears no match for the managerial bureaucracy of the American state.

Musk will step down from his position leading the Department of Government Efficiency at the end of May. At the outset, the tech tycoon was ebullient, promising that DOGE would reduce the budget deficit by $2 trillion, modernize Washington, and curb waste, fraud, and abuse. His marketing plan consisted of memes and social media posts. Indeed, the DOGE brand itself was an ironic blend of memes, Bitcoin, and Internet humor.

Three months later, however, Musk is chastened. Though DOGE succeeded in dismantling USAID, modernizing the federal retirement system, and improving the Treasury Department’s payment security, the initiative as a whole has fallen short. Savings, even by DOGE’s fallible math, will be closer to $100 billion than $2 trillion. Washington is marginally more efficient today than it was before DOGE began, but the department failed to overcome the general tendency of governmental inertia.

Musk’s marketing strategy ran into difficulties, too. His Internet-inflected language was too strange for the average citizen. And the Left, as it always does, countered proposed cuts with sob stories and personal narratives, paired with a coordinated character-assassination attempt portraying Musk as a greedy billionaire eager to eliminate essential services and children’s cancer research.

However meretricious these attacks were, they worked. Musk’s popularity has declined rapidly, and the terror campaign against Tesla drew blood: the company’s stock has slumped in 2025—down around 20 percent—and the board has demanded that Musk return to the helm.

But the deeper problem is that DOGE has always been a confused effort. It promised to cut the federal budget by roughly a third; deliver technocratic improvements to make government efficient; and eliminate waste, fraud, and abuse. As I warned last year, no viable path existed for DOGE to implement these reforms. Further, these promises distracted from what should have been the department’s primary purpose: an ideological purge.

Ironically, this was the one area where DOGE made major progress. In just a few months, the department managed to dismantle one of the most progressive federal agencies, USAID; defund left-wing NGOs, including cutting over $1 billion in grants from the Department of Education; and advance a theory of executive power that enabled the president to slash Washington’s DEI bureaucracy.

Musk also correctly identified the two keys to the kingdom: human resources and payments. DOGE terminated the employment of President Trump’s ideological opponents within the federal workforce and halted payments to the most corrupted institutions, setting the precedent for Trump to withhold funds from the Ivy League universities. At its best, DOGE functioned as a method of targeted de-wokification that forced some activist elements of the Left into recession—a much-needed program, though not exactly what was originally promised.

Ultimately, DOGE succeeded where it could and failed where it could not. Musk’s project expanded presidential power but did not fundamentally change the budget, which still requires congressional approval. Washington’s fiscal crisis is not, at its core, an efficiency problem; it’s a political one. When DOGE was first announced, many Republican congressmen cheered Musk on, declaring, “It’s time for DOGE!” But this was little more than an abdication of responsibility, shifting the burden—and ultimately the blame—onto Musk for Congress’s ongoing failure to take on the politically unpopular task of controlling spending.

With Musk heading back to his companies, it remains to be seen who, if anyone, will take up the mantle of budget reform in Congress. Unfortunately, the most likely outcome is that Republicans will revert to old habits: promising to balance the budget during campaign season and blowing it up as soon as the legislature convenes.

The end of Musk’s tenure at DOGE reminds us that Washington can get the best even of great men. The fight for fiscal restraint is not over, but the illusion that it can be won through efficiency and memes has been dispelled. Our fate lies in the hands of Congress—and that should make Americans pessimistic.

Subscribe to Christopher F. Rufo.

For the full experience, upgrade your subscription.

Automotive

Trump Must Act to Halt the Tesla Terror Campaign

Christopher F. Rufo

Christopher F. Rufo

The Left’s splintering violence threatens a veto over democratic power.

Elon Musk finds himself at the fulcrum of American life. His companies are leading the field across the automotive, space, robotics, and AI industries. His ownership of the social platform X gives him significant influence over political discourse. And his DOGE initiative represents the single greatest threat to the permanent administrative state. Musk is arguably the most powerful man in the United States, including President Trump.

The Left has taken notice. Left-wing activists have long practiced a tactic called “power mapping,” which entails diagramming the opposing political movement and identifying “chokepoints.” They have designated Musk as one such chokepoint. This month, activists claimed to have organized 500 protests against Elon Musk’s Tesla—dubbed the “Tesla Takedown”—with demonstrations outside sales lots and a series of incidents of vandalism, property destruction, and fire bombings. A pattern has also emerged of individuals scratching or spray-painting parked Teslas, looking to intimidate owners and potential owners or just to express hatred of Musk.

Precedents exist for this kind of escalation. In the 1970s, following the frustrations of the civil rights era, left-wing splinter groups launched targeted terror campaigns and symbolic acts of violence. They bombed the U.S. Capitol, assassinated police officers, and even self-immolated in imitation of Buddhist monks. We may be entering a similar phase today, as the collapse of the Black Lives Matter movement gives rise to radicalized left-wing factions willing to embrace violence. If so, Musk’s Tesla may be the Number One target.

What, exactly, motivates this campaign? At its core, the Left appears to be shifting from an “antiracist” narrative to an anti-wealth one—from a racial frame to an economic one. The sentiment driving the Tesla Takedown is rooted in economic resentment and a desire for leveling. Musk has become a symbol of everything progressives oppose: oligarchy, capitalism, wealth, and innovation. These, in their view, are marks of the oppressor. They scorn the futuristic Cybertruck, SpaceX rockets, and Optimus robots, believing that such creations should be dismantled and repurposed into chassis for public buses or I-beams for public housing.

A certain element of left-wing Luddism is at work here, but the greater part of these activists’ motives is resentment. Musk represents the triumph of the great man of industry, something the Left believes should not exist.

Unfortunately, the Tesla Takedown may succeed. The Left has likely identified Tesla as a chokepoint because it’s easier to dissuade consumers from buying a car they associate with a malevolent political cause—or fear might be vandalized—than it is to persuade them to buy one in support of Musk and DOGE. When it comes to purchasing a Tesla, fear among the average American is a more powerful motivator than enthusiasm among the MAGA base.

Some evidence suggests that the campaign has made an economic impact. Tesla stock peaked around the time of President Trump’s inauguration and since then has lost approximately 40 percent of its value. Musk has accumulated more power than any other American, but that means that he has more points of vulnerability. His wealth and power are tied to his companies—most importantly, his consumer car company, which depends on individual purchases rather than institutional contracts (like SpaceX).

Trump has signaled that he understands this dilemma. He appeared at the White House in a Tesla and has voiced support for Musk’s firms. Justice Department prosecutors—and their allies in state government—must translate this support into policy by identifying and punishing those who destroy property as a means of political intimidation.

The administration needs to make clear that radical left-wing factions cannot use violence to wield a veto over democratic governance. If the partnership between Trump and Musk is to produce meaningful results, it must be backed by the full protection of the law.

-

Crime1 day ago

Crime1 day agoHow Chinese State-Linked Networks Replaced the Medellín Model with Global Logistics and Political Protection

-

Addictions1 day ago

Addictions1 day agoNew RCMP program steering opioid addicted towards treatment and recovery

-

Aristotle Foundation1 day ago

Aristotle Foundation1 day agoWe need an immigration policy that will serve all Canadians

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoNatural gas pipeline ownership spreads across 36 First Nations in B.C.

-

Courageous Discourse23 hours ago

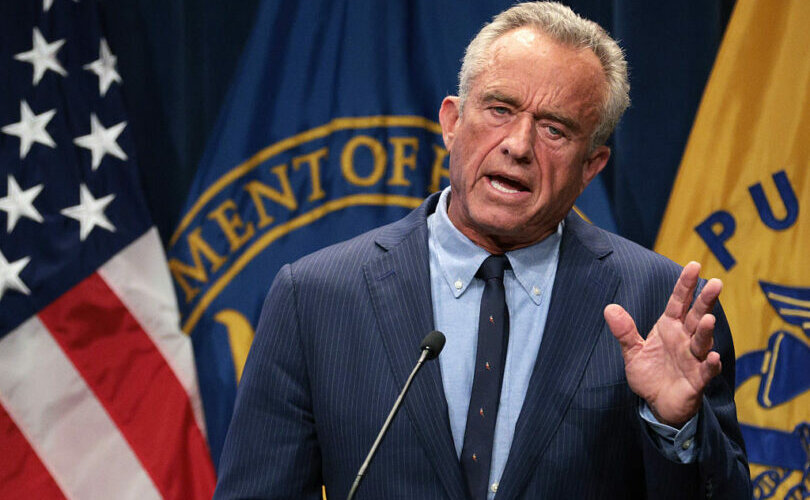

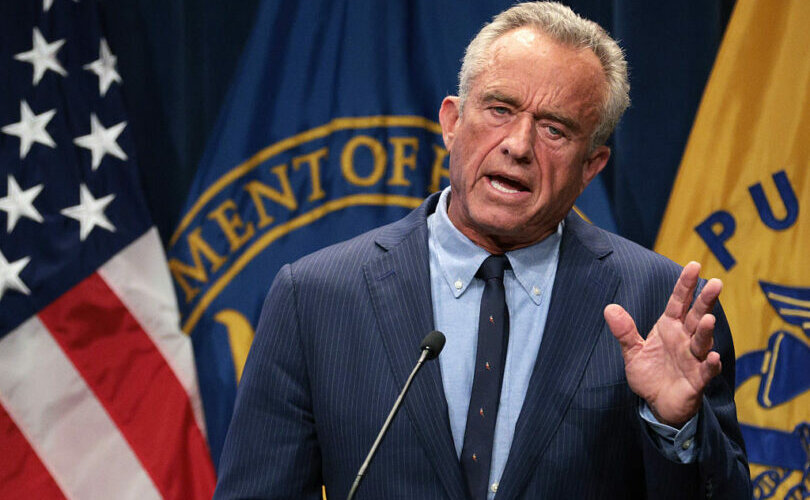

Courageous Discourse23 hours agoHealthcare Blockbuster – RFK Jr removes all 17 members of CDC Vaccine Advisory Panel!

-

Business5 hours ago

Business5 hours agoEU investigates major pornographic site over failure to protect children

-

Health19 hours ago

Health19 hours agoRFK Jr. purges CDC vaccine panel, citing decades of ‘skewed science’

-

Censorship Industrial Complex22 hours ago

Censorship Industrial Complex22 hours agoAlberta senator wants to revive lapsed Trudeau internet censorship bill