Frontier Centre for Public Policy

We should follow New Zealand on housing and free up more land for growth

From the Frontier Centre for Public Policy

By Wendell Cox

Attempts to contain ‘urban sprawl’ have driven land prices sky-high. It’s time to abandon densification strategies.

Not so long ago, house prices tended to be around three times household incomes in most housing markets in Canada, the U.S., the U.K., Ireland, Australia and New Zealand. But over the past half-century, many local and provincial governments have tried to stop the expansion of urban areas (so-called “sprawl”) by means of urban growth boundaries, greenbelts and other containment strategies.

Though pleasing to planners, the results have been disastrous for middle- and lower-income households, sending housing prices through the roof, lowering living standards and even increasing poverty. International research has associated urban containment with escalating the underlying price of land, not only on the urban fringe where the city meets rural areas, but also throughout the contained area.

Canada’s current housing affordability crisis is centred in “census metropolitan areas” that have tried containment. Vancouver, which routinely places second or third least affordable of 94 major metropolitan areas in the annual Demographia International Housing Affordability report, has experienced a tripling of house prices compared to incomes. In the third quarter of last year, the median house price was 12.3 times median household income. In less than two decades, the Toronto CMA has experienced a doubling of its house price/income ratio, to 9.3.

Not surprisingly, both CMAs are seeing huge net departures, principally to less expensive markets nearby, such as Kitchener-Waterloo, Guelph, London, Nanaimo, Chilliwack and Kelowna. But these areas are also experiencing vanishing affordability as they too impose Vancouver- and Toronto-like policies.

In recent years, Canadian governments have adopted densification strategies — on the assumption that making cities more crowded will restore housing affordability. But evidence of that is limited. Yonah Freemark of the Urban Institute characterizes the literature as indicating “that upzonings offer mixed success in terms of housing production, reduced costs, and social integration in impacted neighborhoods; outcomes depend on market demand, local context, housing types, and timing.”

Like Canada, New Zealand has seen its house prices grow much faster than household incomes, also mainly because of urban containment policies. Auckland routinely ranks as one of the world’s least affordable markets. But in what may be a watershed moment for housing policy worldwide, New Zealand’s recently elected coalition government is giving up on densification and instead, with its Going for Housing Growth program, is aiming at the heart of the issue by addressing the cost of land.

Under new proposals, local governments will be required to zone enough land for 30 years of projected growth and make it available for immediate development. According to the government, local governments’ deliberate decision to restrain growth on their fringes has “driven up the price of land, which has flowed through to house prices,” and it cites research indicating that “urban growth boundaries add NZ$600,000 (C$500,000) to the cost of land for houses in Auckland’s fringes.”

The new policy will rely on a 2020 act allowing public agencies and private developers to establish “Special Purpose Vehicles” — corporations established for financing housing-related infrastructure, with the costs to be repaid by homeowners over up to 50 years. This removes the infrastructure burden from governments, as has also been done in “municipal utility districts” (MUDs) in Texas and Colorado. MUDs are independent entities empowered to issue bonds and collect fees to finance and manage local infrastructure for new developments.

New Zealand’s government believes guaranteeing plentiful access to land will result in an increased supply “inside and at the edge of our cities … so that land prices are not inflated by artificial planning restrictions.” The same strategy could help here. Unlike most urban planners, most Canadians do not want higher population density. A 2019 survey of younger Canadian households by the Mustel Group and Sotheby’s found that on average across four metropolitan areas (Toronto, Montreal, Vancouver and Calgary) 83 per cent of such families preferred detached houses, though only 56 per cent had actually bought one.

Households that move from the big city to Kitchener-Waterloo, say, or Chilliwack not only want to save money, they also want more house and probably a yard. Detached housing predominates in these affordability sanctuaries, compared to the Vancouver and Toronto CMAs.

Urban planners continue to complain about urban expansion, but that is how organic urban growth occurs. Toronto and Vancouver show that the cost of taming expansion is unacceptably high: inflated house prices, higher rents and, for increasing numbers of people, poverty. It is time to prioritize the well-being of Canadian households, not urban planners.

Wendell Cox, a senior fellow at the Frontier Centre for Public Policy, is author of the Centre’s annual Demographia International Housing Affordability report.

Crime

How Global Organized Crime Took Root In Canada

From the Frontier Centre for Public Policy

Weak oversight and fragmented enforcement are enabling criminal networks to undermine Canada’s economy and security, requiring a national-security-level response to dismantle these systems

A massive drug bust reveals how organized crime has turned Canada into a source of illicit narcotics production

Canada is no longer just a victim of the global drug trade—it’s becoming a source. The country’s growing role in narcotics production exposes deep systemic weaknesses in oversight and enforcement that are allowing organized crime to take root and threaten our economy and security.

Police in Edmonton recently seized more than 60,000 opium poppy plants from a northeast property, one of the largest domestic narcotics cultivation operations in Canadian history. It’s part of a growing pattern of domestic production once thought limited to other regions of the world.

This wasn’t a small experiment; it was proof that organized crime now feels confident operating inside Canada.

Transnational crime groups don’t gamble on crops of this scale unless they know their systems are solid. You don’t plant 60,000 poppies without confidence in your logistics, your financing and your buyers. The ability to cultivate, harvest and quietly move that volume of product points to a level of organization that should deeply concern policymakers. An operation like this needs more than a field; it reflects the convergence of agriculture, organized crime and money laundering within Canada’s borders.

The uncomfortable truth is that Canada has become a source country for illicit narcotics rather than merely a consumer or transit point. Fentanyl precursors (the chemical ingredients used to make the synthetic opioid) arrive from abroad, are synthesized domestically and are exported south into the United States. Now, with opium cultivation joining the picture, that same capability is extending to traditional narcotics production.

Criminal networks exploit weak regulatory oversight, land-use gaps and fragmented enforcement, often allowing them to operate in plain sight. These groups are not only producing narcotics but are also embedding themselves within legitimate economic systems.

This isn’t just crime; it’s the slow undermining of Canada’s legitimate economy. Illicit capital flows can distort real estate markets, agricultural valuations and financial transparency. The result is a slow erosion of lawful commerce, replaced by parallel economies that profit from addiction, money laundering and corruption. Those forces don’t just damage national stability—they drive up housing costs, strain health care and undermine trust in Canada’s institutions.

Canada’s enforcement response remains largely reactive, with prosecutions risk-averse and sentencing inadequate as a deterrent. At the same time, threat networks operate with impunity and move seamlessly across the supply chain.

The Edmonton seizure should therefore be read as more than a local success story. It is evidence that criminal enterprise now operates with strategic depth inside Canada. The same confidence that sustains fentanyl synthesis and cocaine importation is now manifesting in agricultural narcotics production. This evolution elevates Canada from passive victim to active threat within the global illicit economy.

Reversing this dynamic requires a fundamental shift in thinking. Organized crime is a matter of national security. That means going beyond raids and arrests toward strategic disruption: tracking illicit finance, dismantling logistical networks that enable these operations and forging robust intelligence partnerships across jurisdictions and agencies.

It’s not about symptoms; it’s about knocking down the systems that sustain this criminal enterprise operating inside Canada.

If we keep seeing narcotics enforcement as a public safety issue instead of a warning of systemic corruption, Canada’s transformation into a threat nation will be complete. Not because of what we import but because of what we now produce.

Scott A. McGregor is a senior fellow with the Frontier Centre for Public Policy and managing partner of Close Hold Intelligence Consulting Ltd.

Business

The Payout Path For Indigenous Claims Is Now National Policy

From the Frontier Centre for Public Policy

By Tom Flanagan

Ottawa’s refusal to test Indigenous claims in court is fuelling a billion-dollar wave of settlements and legal copycats

First Nations led the charge. Now the Métis are catching up. Ottawa’s legal surrender strategy could make payouts the new national policy.

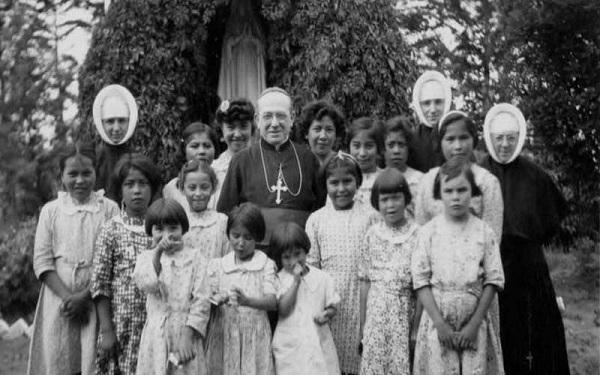

Indigenous class-action litigation seeking compensation for historical grievances began in earnest with claims related to Indian Residential Schools. The federal government eventually chose negotiation over litigation, settling for about $5-billion with “survivors.” Then–prime minister Stephen Harper hoped this would close the chapter, but it opened the floodgates instead. Class actions have followed ever since.

By 2023, the federal government had paid or committed $69.6-billion in 2023 dollars to settle these claims. What began with residential schools expanded into day schools, boarding homes, the “Sixties Scoop,” unsafe drinking water, and foster-care settlements.

Most involved status Indians. Métis claims had generally been unsuccessful—until now.

Download the Essay. (4 pages)

Tom Flanagan is professor emeritus of political science at the University of Calgary and a senior fellow of the Frontier Centre for Public Policy.

-

Health2 days ago

Health2 days agoCDC’s Autism Reversal: Inside the Collapse of a 25‑Year Public Health Narrative

-

Crime2 days ago

Crime2 days agoCocaine, Manhunts, and Murder: Canadian Cartel Kingpin Prosecuted In US

-

Health2 days ago

Health2 days agoBREAKING: CDC quietly rewrites its vaccine–autism guidance

-

National2 days ago

National2 days agoPsyop-Style Campaign That Delivered Mark Carney’s Win May Extend Into Floor-Crossing Gambits and Shape China–Canada–US–Mexico Relations

-

Energy2 days ago

Energy2 days agoHere’s what they don’t tell you about BC’s tanker ban

-

Daily Caller2 days ago

Daily Caller2 days agoBREAKING: Globalist Climate Conference Bursts Into Flames

-

Bruce Dowbiggin2 days ago

Bruce Dowbiggin2 days agoBurying Poilievre Is Job One In Carney’s Ottawa

-

Great Reset1 day ago

Great Reset1 day agoEXCLUSIVE: A Provincial RCMP Veterans’ Association IS TARGETING VETERANS with Euthanasia