Fraser Institute

Australia’s universal health-care system outperforms Canada on key measures including wait times, costs less and includes large role for private hospitals

The Role of Private Hospitals in Australia’s Universal Health Care System

From the Fraser Institute

by Mackenzie Moir and Bacchus Barua

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, provincial governments across Canada relied on private

clinics in order to deliver a limited number of publicly funded surgeries in a bid to clear unprecedented

surgical backlogs. Subsequently, surveys indicated that 78% of Canadians support allowing more

surgeries and tests performed in private clinics while 40% only support this policy to clear the

surgical backlog. While a majority of Canadians are either supportive (or at the very least curious)

about these arrangements, the use of private clinics continues to be controversial and raise questions

around their compatibility with the provision of universal care.

The reality is that private hospitals play a key role in delivering care to patients in other countries with universal health care. Canada is only one of 30 high-income countries with universal care and many of these countries involve the private-sector in their health-care systems to a wide extent while performing better than Canada.

Australia is one of these countries and routinely outperforms Canada on key indicators of health-care performance while spending at a similar or lower level. Like Canada, Australia ranked

in the top ten for health-care spending (as a percentage of GDP and per capita) in 2020. However, after adjusting for the age of the population, it outperforms Canada on 33 (of 36) measures of performance.

Importantly, Australia outperformed Canada on a number of key measures such as the availability of physicians, nurses, hospital beds, CT scanners, and MRI machines. Australia also outperformed

Canada on every indicator of timely access to care, including ease of access to after-hours care, same-day primary care appointments, and, crucially, timely access to elective surgical care and specialist appointments.

Australia’s universal system is also characterized by a deep integration between the public and private sectors in the financing and delivery of care. Universal health-insurance coverage is provided through its public system known as Medicare. However, Australia also has a large private health-care sector that also finances and delivers medical services. Around half of the Australian population (55.2% in 2021/22) benefit from private health-insurance coverage provided by 33 registered not-for-profit and for-profit private insurance companies.

Private hospitals (for profit and not for profit) made up nearly half (48.5%) of all Australian hospitals in 2016 and contain a third of all care beds. These hospitals are a major partner in the delivery of care in Australia. For example, in 2021/22 41% of all recorded episodes of hospital care occurred in private hospitals. While delivering a small minority of emergency care (8.2%), private hospitals delivered the majority of recorded elective care (58.6%) and 70.3% of elective admissions involving surgery.

Private hospitals primarily deliver care to fully funded public patients in two ways. The first is contracted

care, either through ad hoc inter-hospital contracts or formal programs. Fully publicly funded episodes of care occurring in private hospitals made up 6.4% of all care in private hospitals, while representing 2.6% of all recorded care. The second way is privately delivered care paid for through the Department of Veterans’ Affairs. A full 73.5% of care paid for by the Department of Veterans’ Affairs occurred in private hospitals.

It would be easy, however, to underestimate the significance of this public-private partnership by examining only the delivery of care that is fully publicly funded. Privately insured care is also partially subsidized by the government, at a rate of 75% of the public fee. Therefore, in order to understand the full extent of publicly funded or subsidized care in private hospitals, it is helpful to examine private hospital expenditures by the source of funds. In 2019/20, 32.8% of private hospital expenditures came from government sources, 18.2% of which came from private health-insurance rebates. This means that a full

third of private hospital expenditure comes from a range of public sources, including the federal government.

Overall, private hospitals are important partners in the delivery of care within the Australian universal healthcare system. The Australian system outranks Canada’s on a range of performance indicators, while spending less as a percentage of GDP. Further, the integration of private hospitals into the delivery of care, including public care, occurs while maintaining universal access for residents.

Authors:

More from this study

Alberta

Albertans need clarity on prime minister’s incoherent energy policy

From the Fraser Institute

By Tegan Hill

The new government under Prime Minister Mark Carney recently delivered its throne speech, which set out the government’s priorities for the coming term. Unfortunately, on energy policy, Albertans are still waiting for clarity.

Prime Minister Carney’s position on energy policy has been confusing, to say the least. On the campaign trail, he promised to keep Trudeau’s arbitrary emissions cap for the oil and gas sector, and Bill C-69 (which opponents call the “no more pipelines act”). Then, two weeks ago, he said his government will “change things at the federal level that need to be changed in order for projects to move forward,” adding he may eventually scrap both the emissions cap and Bill C-69.

His recent cabinet appointments further muddied his government’s position. On one hand, he appointed Tim Hodgson as the new minister of Energy and Natural Resources. Hodgson has called energy “Canada’s superpower” and promised to support oil and pipelines, and fix the mistrust that’s been built up over the past decade between Alberta and Ottawa. His appointment gave hope to some that Carney may have a new approach to revitalize Canada’s oil and gas sector.

On the other hand, he appointed Julie Dabrusin as the new minister of Environment and Climate Change. Dabrusin was the parliamentary secretary to the two previous environment ministers (Jonathan Wilkinson and Steven Guilbeault) who opposed several pipeline developments and were instrumental in introducing the oil and gas emissions cap, among other measures designed to restrict traditional energy development.

To confuse matters further, Guilbeault, who remains in Carney’s cabinet albeit in a diminished role, dismissed the need for additional pipeline infrastructure less than 48 hours after Carney expressed conditional support for new pipelines.

The throne speech was an opportunity to finally provide clarity to Canadians—and specifically Albertans—about the future of Canada’s energy industry. During her first meeting with Prime Minister Carney, Premier Danielle Smith outlined Alberta’s demands, which include scrapping the emissions cap, Bill C-69 and Bill C-48, which bans most oil tankers loading or unloading anywhere on British Columbia’s north coast (Smith also wants Ottawa to support an oil pipeline to B.C.’s coast). But again, the throne speech provided no clarity on any of these items. Instead, it contained vague platitudes including promises to “identify and catalyse projects of national significance” and “enable Canada to become the world’s leading energy superpower in both clean and conventional energy.”

Until the Carney government provides a clear plan to address the roadblocks facing Canada’s energy industry, private investment will remain on the sidelines, or worse, flow to other countries. Put simply, time is up. Albertans—and Canadians—need clarity. No more flip flopping and no more platitudes.

Fraser Institute

Long waits for health care hit Canadians in their pocketbooks

From the Fraser Institute

Canadians continue to endure long wait times for health care. And while waiting for care can obviously be detrimental to your health and wellbeing, it can also hurt your pocketbook.

In 2024, the latest year of available data, the median wait—from referral by a family doctor to treatment by a specialist—was 30 weeks (including 15 weeks waiting for treatment after seeing a specialist). And last year, an estimated 1.5 million Canadians were waiting for care.

It’s no wonder Canadians are frustrated with the current state of health care.

Again, long waits for care adversely impact patients in many different ways including physical pain, psychological distress and worsened treatment outcomes as lengthy waits can make the treatment of some problems more difficult. There’s also a less-talked about consequence—the impact of health-care waits on the ability of patients to participate in day-to-day life, work and earn a living.

According to a recent study published by the Fraser Institute, wait times for non-emergency surgery cost Canadian patients $5.2 billion in lost wages in 2024. That’s about $3,300 for each of the 1.5 million patients waiting for care. Crucially, this estimate only considers time at work. After also accounting for free time outside of work, the cost increases to $15.9 billion or more than $10,200 per person.

Of course, some advocates of the health-care status quo argue that long waits for care remain a necessary trade-off to ensure all Canadians receive universal health-care coverage. But the experience of many high-income countries with universal health care shows the opposite.

Despite Canada ranking among the highest spenders (4th of 31 countries) on health care (as a percentage of its economy) among other developed countries with universal health care, we consistently rank among the bottom for the number of doctors, hospital beds, MRIs and CT scanners. Canada also has one of the worst records on access to timely health care.

So what do these other countries do differently than Canada? In short, they embrace the private sector as a partner in providing universal care.

Australia, for instance, spends less on health care (again, as a percentage of its economy) than Canada, yet the percentage of patients in Australia (33.1 per cent) who report waiting more than two months for non-emergency surgery was much higher in Canada (58.3 per cent). Unlike in Canada, Australian patients can choose to receive non-emergency surgery in either a private or public hospital. In 2021/22, 58.6 per cent of non-emergency surgeries in Australia were performed in private hospitals.

But we don’t need to look abroad for evidence that the private sector can help reduce wait times by delivering publicly-funded care. From 2010 to 2014, the Saskatchewan government, among other policies, contracted out publicly-funded surgeries to private clinics and lowered the province’s median wait time from one of the longest in the country (26.5 weeks in 2010) to one of the shortest (14.2 weeks in 2014). The initiative also reduced the average cost of procedures by 26 per cent.

Canadians are waiting longer than ever for health care, and the economic costs of these waits have never been higher. Until policymakers have the courage to enact genuine reform, based in part on more successful universal health-care systems, this status quo will continue to cost Canadian patients.

-

Crime1 day ago

Crime1 day agoHow Chinese State-Linked Networks Replaced the Medellín Model with Global Logistics and Political Protection

-

Addictions1 day ago

Addictions1 day agoNew RCMP program steering opioid addicted towards treatment and recovery

-

Aristotle Foundation1 day ago

Aristotle Foundation1 day agoWe need an immigration policy that will serve all Canadians

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoNatural gas pipeline ownership spreads across 36 First Nations in B.C.

-

Courageous Discourse1 day ago

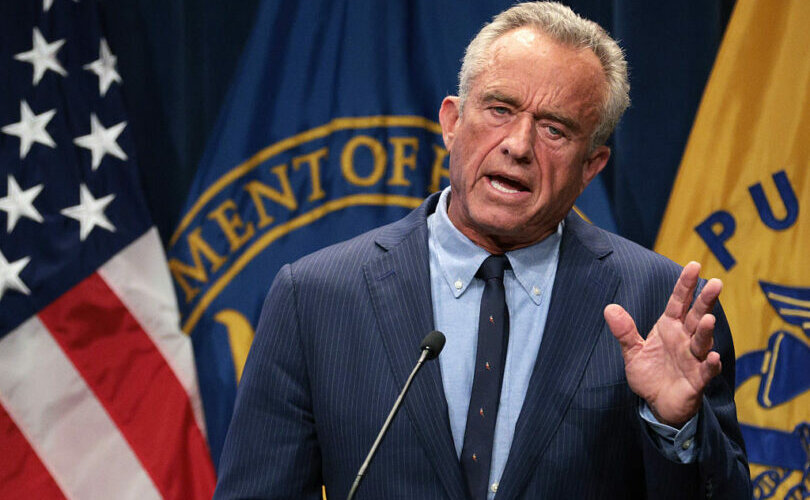

Courageous Discourse1 day agoHealthcare Blockbuster – RFK Jr removes all 17 members of CDC Vaccine Advisory Panel!

-

Business11 hours ago

Business11 hours agoEU investigates major pornographic site over failure to protect children

-

Health1 day ago

Health1 day agoRFK Jr. purges CDC vaccine panel, citing decades of ‘skewed science’

-

Censorship Industrial Complex1 day ago

Censorship Industrial Complex1 day agoConservatives slam Liberal bill to allow police to search through Canadians’ mail