Break The Needle

Why psychedelic therapy is stuck in the waiting room

There is mounting evidence of psychedelics’ effectiveness at treating mental disorders. But researchers face obstacles conducting rigorous studies

In a move that made international headlines, America’s top drug regulator denied approval last year for psychedelic-assisted therapy to treat post-traumatic stress disorder.

In its decision, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration cited concerns about study design and inadequate evidence to assess the benefits and harms of using the drug MDMA.

The decision was a significant setback for psychedelics researchers and veterans’ groups who had been advocating for the therapy to be approved. It is also reflective of a broader challenge faced by researchers keen to validate the therapeutic potential of psychedelics.

“Sometimes I feel like it’s death by 1,000 paper cuts,” said Leah Mayo, a researcher at the University of Calgary.

“If the regulatory burden were a little bit less, that would be helpful,” added Mayo, who holds the Parker Psychedelics Research Chair at the Psychedelic and Cannabinoid Therapeutics Lab. The lab develops new treatments for mental health disorders using psychedelics and cannabinoids.

Sources say the weak research body behind psychedelics is due to a complex interplay of factors. But they would like to see more research conducted to make psychedelics more accessible to people who could benefit from them.

“If you want [psychedelics] to work within existing health-care infrastructure, you have to play by [Canadian research] rules,” said Mayo.

“Therapy has to be reproducible, it has to be evidence-based, it has to be grounded in reality.”

Psychedelics in Canada

Psychedelics are hallucinogenic substances such as psilocybin, MDMA and ketamine that alter people’s perceptions, mood and thought processes. Psychedelic therapy involves the use of psychedelics in guided sessions with therapists to treat mental health conditions.

Psychedelics are generally banned for possession, production and distribution in Canada. However, two per cent of Canadians consumed hallucinogens in 2019, according to the latest Canadian Alcohol and Drugs Survey. Psychedelics are also used in Canada and abroad in unregulated clinics and settings to treat conditions such as substance use disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and various mental disorders.

“The cat’s out of the bag, and people are using this,” said Zachary Walsh, a professor in the Department of Psychology at the University of British Columbia.

Within Canada, there are three ways for psychedelics to be accessed legally.

The federal health minister can approve their use for medical, scientific or public interest purposes. Health Canada runs a Special Access Program that allows doctors to request the use of unapproved drugs for patients with serious conditions that have not responded to other treatments. And Health Canada can approve psychedelics for use in clinical trials.

Researchers interested in conducting clinical trials involving psychedelics face significant hurdles.

“There’s been a concerted effort — and it’s just fading now — to mischaracterize the risks of these substances,” said Walsh, who has conducted several studies on the therapeutic uses of psychedelics. These include studies on MDMA-assisted therapy for PTSD, and the effects of microdosing psilocybin on stress, anxiety and depression.

This Substack is reader-supported.

To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

The U.S. government demonized psychedelic substances during its War on Drugs in the 1970s, exaggerating their risks and blocking research into their medical potential. Influenced by this war, Canada adopted similar tough-on-drugs policies and restricted research.

Today, younger researchers are pushing forward.

“New ideas really come into the forefront when the people in charge of the old ideas retire and die,” said Norman Farb, an associate professor in the Department of Psychology at the University of Toronto.

But it remains a challenge to secure funding for psychedelic research. Government funding is limited, and pharmaceutical companies are often hesitant to invest because psychedelic-assisted therapy does not generally fit the traditional pharmaceutical model.

“It’s not something that a pharmaceutical company wants to pay for, because it’s not going to be a classic pharmaceutical,” said Walsh.

As a result, many researchers rely on private donations or venture capital. This makes it difficult to fund large-scale studies, says Farb, who has faced institutional obstacles researching microdosing for treatment-resistant depression.

“No one wants to be that first cautionary tale,” he said. “No one wants to invest a lot of money to do the kind of study that would be transparent if it didn’t work.”

Difficulties in clinical trials

But funding is not the only challenge. Sources also pointed to the difficulty of designing clinical trials for psychedelics.

In particular, it can be difficult to implement a blind trial process, given the potent effects of psychedelics. Double blind trials are the gold standard of clinical trials, where neither the person administering the drug or patient knows if the patient is receiving the active drug or placebo.

Health Canada also requires researchers to meet strict trial criteria, such as demonstrating that the benefits outweigh the risks, that the drug treats an ongoing condition with no other approved treatments, and that the drug’s effects exceed any placebo effect.

It is especially difficult to isolate the effects of psychedelics. Psychotherapy, for example, can play a crucial role in treatment, making it difficult to disentangle the role of therapy from the drugs.

Mayo, of the University of Calgary, worries the demands of clinical trial models are not practical given the limitations of Canada’s health-care system.

“The way we’re writing these clinical trials, it’s not possible within our existing health-care infrastructure,” she said. She cited as one example the expectation that psychiatrists in clinical trials spend eight or more hours with each patient.

Ethical issues

Psychedelics research can also raise ethical concerns, particularly where it involves individuals with pre-existing mental health conditions.

A 2024 study found that people who visited an emergency room after using hallucinogens were at a significantly increased risk of developing schizophrenia — raising concerns that trials could harm vulnerable participants.

Another problem is a lack of standardization in psychedelic therapy. “We haven’t standardized it,” said Mayo. “We don’t even know what people are being taught psychedelic therapy is.”

This concern was underscored in a 2015 clinical trial on MDMA in Canada, where one of the trial participants was subjected to inappropriate physical contact and questioning by two unlicensed therapists.

Mayo advocates for the creation of a regulatory body to standardize therapist training and prevent misconduct.

Others have raised concerns about whether the research exploits Indigenous knowledge or cultural practices.

“There’s no psychedelic science without Indigenous communities,” said Joseph Mays, a doctorate candidate at the University of Saskatchewan.

“Whether it’s medicalized or ceremonial, there’s a direct continuity with Indigenous practices.”

Mays is an advisor to the Indigenous Reciprocity Initiative, which funnels psychedelic investments back to Indigenous communities. He believes those working with psychedelics must incorporate reciprocity into their work.

“If you’re using psychedelics in any way, it only makes sense that you would also have a commitment to fighting for the rights of [Indigenous] communities, which are still lacking basic necessities,” said Mays, suggesting that companies profiting from psychedelic medicine should contribute to Indigenous causes.

Despite these various challenges, sources remained optimistic that psychedelics would eventually be legalized — although not due to their work.

“It’s inevitable,” said Mays. “They’re already widespread, being used underground.”

Farb agrees. “A couple more research studies is not going to change the law,” he said. “Power is going to change the law.”

This article was produced through the Breaking Needles Fellowship Program, which provided a grant to Canadian Affairs, a digital media outlet, to fund journalism exploring addiction and crime in Canada. Articles produced through the Fellowship are co-published by Break The Needle and Canadian Affairs.

Subscribe to Break The Needle.

Our content is always free – but if you want to help us commission more high-quality journalism, consider getting a voluntary paid subscription.

Addictions

No, Addicts Shouldn’t Make Drug Policy

By Adam Zivo

Canada’s policy of deferring to the “leadership” of drug users has proved predictably disastrous. The United States should take heed.

[This article was originally published in City Journal, a public policy magazine and website published by the Manhattan Institute for Policy Research]

Progressive “harm reduction” advocates have insisted for decades that active users should take a central role in crafting drug policy. While this belief is profoundly reckless—akin to letting drunk drivers set traffic laws—it is now entrenched in many left-leaning jurisdictions. The harms and absurdities of the position cannot be understated.

While the harm-reduction movement is best known for championing public-health interventions that supposedly minimize the negative effects of drug use, it also has a “social justice” component. In this context, harm reduction tries to redefine addicts as a persecuted minority and illicit drug use as a human right.

This campaign traces its roots to the 1980s and early 1990s, when “queer” activists, desperate to reduce the spread of HIV, began operating underground needle exchanges to curb infections among drug users. These exchanges and similar efforts allowed some more extreme LGBTQ groups to form close bonds with addicts and drug-reform advocates. Together, they normalized the concept of harm reduction, such that, within a few years, needle exchanges would become officially sanctioned public-health interventions.

The alliance between these more radical gay rights advocates and harm-reduction proponents proved enduring. Drug addiction remained linked to HIV, and both groups shared a deep hostility to the police, capitalism, and society’s “moralizing” forces.

In the 1990s, harm-reduction proponents imitated the LGBTQ community’s advocacy tactics. They realized that addicts would have greater political capital if they were considered a persecuted minority group, which could legitimize their demands for extensive accommodations and legal protections under human rights laws. Harm reductionists thus argued that addiction was a kind of disability, and that, like the disabled, active users were victims of social exclusion who should be given a leading role in crafting drug policy.

These arguments were not entirely specious. Addiction can reasonably be considered a mental and physical disability because illicit drugs hijack users’ brains and bodies. But being disabled doesn’t necessarily mean that one is part of a persecuted group, much less that one should be given control over public policy.

More fundamentally, advocates were wrong to argue that the stigma associated with drug addiction was senseless persecution. In fact, it was a reasonable response to anti-social behavior. Drug addiction severely impairs a person’s judgement, often making him a threat to himself and others. Someone who is constantly high and must rob others to fuel his habit is a self-evident danger to society.

Despite these obvious pitfalls, portraying drug addicts as a persecuted minority group became increasingly popular in the 2000s, thanks to several North American AIDS organizations that pivoted to addiction work after the HIV epidemic subsided.

In 2005, the Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network published a report titled “Nothing about us without us.” (The nonprofit joined other groups in publishing an international version in 2008.) The 2005 report included a “manifesto” written by Canadian drug users, who complained that they were “among the most vilified and demonized groups in society” and demanded that policymakers respect their “expertise and professionalism in addressing drug use.”

The international report argued that addiction qualified as a disability under international human rights treaties, and called on governments to “enact anti-discrimination or protective laws to reduce human rights violations based on dependence to drugs.” It further advised that drug users be heavily involved in addiction-related policy and decision-making bodies; that addict-led organizations be established and amply funded; and that “community-based organizations . . . increase involvement of people who use drugs at all levels of the organization.”

While the international report suggested that addicts could serve as effective policymakers, it also presented them as incapable of basic professionalism. In a list of “do’s and don’ts,” the authors counseled potential employers to pay addicts in cash and not to pass judgment if the money were spent on drugs. They also encouraged policymakers to hold meetings “in a low-key setting or in a setting where users already hang out,” and to avoid scheduling meetings at “9 a.m., or on welfare cheque issue day.” In cases where addicts must travel for policy-related work, the report recommended policymakers provide “access to sterile injecting equipment” and “advice from a local person who uses drugs.”

The international report further asserted that if an organization’s employees—even those who are former drug users—were bothered by the presence of addicts, then management should refer those employees to counselling at the organization’s expense. “Under no circumstances should [drug addicts] be reprimanded, singled out or made to feel responsible in any way for the triggering responses of others,” stressed the authors.

Reflecting the document’s general hostility to recovery, the international report emphasized that former drug addicts “can never replace involvement of active users” in public policy work, because people in recovery “may be somewhat disconnected from the community they seek to represent, may have other priorities than active users, may sometimes even have different and conflicting agenda, and may find it difficult to be around people who currently use drugs.”

Subscribe for free to get BTN’s latest news and analysis – or donate to our investigative journalism fund.

The messaging in these reports proved highly influential throughout the 2000s and 2010s. In Canada, federal and provincial human rights legislation expanded to protect active addicts on the basis of disability. Reformers in the United States mirrored Canadian activists’ appeals to addicts’ “lived experience,” albeit with less success. For now, American anti-discrimination protections only extend to people who have a history of addiction but who are not actively using drugs.

The harm reduction movement reached its zenith in the early 2020s, after the Covid-19 pandemic swept the world and instigated a global spike in addiction. During this period, North American drug-reform activists again promoted the importance of treating addicts like public-health experts.

Canada was at the forefront of this push. For example, the Canadian Association of People Who Use Drugs released its “Hear Us, See Us, Respect Us” report in 2021, which recommended that organizations “deliberately choose to normalize the culture of drug use” and pay addicts $25-50 per hour. The authors stressed that employers should pay addicts “under the table” in cash to avoid jeopardizing access to government benefits.

These ideas had a profound impact on Canadian drug policy. Throughout the country, public health officials pushed for radical pro-drug experiments, including giving away free heroin-strength opioids without supervision, simply because addicts told researchers that doing so would be helpful. In 2024, British Columbia’s top doctor even called for the legalization of all illicit drugs (“non-medical safer supply”) primarily on the basis of addict testimonials, with almost no other supporting evidence.

For Canadian policymakers, deferring to the “lived experiences” and “leadership” of drug users meant giving addicts almost everything they asked for. The results were predictably disastrous: crime, public disorder, overdoses, and program fraud skyrocketed. Things have been less dire in the United States, where the harm reduction movement is much weaker. But Americans should be vigilant and ensure that this ideology does not flower in their own backyard.

Subscribe to Break The Needle.

Our content is always free – but if you want to help us commission more high-quality journalism,

consider getting a voluntary paid subscription.

Addictions

‘Greening out’: Experts call for THC limits in cannabis products

Experts warn surging THC levels are fuelling growing health risks — and say stronger regulation is urgently needed

More and more cannabis users are ending up in emergency rooms suffering from severe, repeated bouts of vomiting — a condition known as cannabis hyperemesis syndrome.

A new study found that emergency visits for cannabis hyperemesis syndrome increased 13-fold over eight years, accounting for more than 8,000 of the nearly 13,000 cannabis-related ER visits in that period.

Experts say the mounting health risks associated with cannabis use are due to rising THC levels in cannabis products. They urge stronger regulation, better labeling and more research — using Quebec’s approach as a potential model.

“I don’t think we have the perfect model in Quebec — there’s pros and cons,” said Dr. Didier Jutras-Aswad, a clinical scientist at the Centre hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal (CHUM) and a professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Addiction at Université de Montréal.

“But overall, the process of … progressively implementing changes, not wanting to be the first one in line to put all this new product on the market, I think is probably, in terms of public health, more prudent.”

THC levels

Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) is the primary psychoactive compound in cannabis and what causes the “high.” It is one of more than 100 cannabinoids, or chemical compounds, naturally found in the cannabis plant.

Delta‑9‑THC is the most common and well-studied form, though other forms of THC exist and are less understood.

Federal drug laws place strict limits on delta-9-THC levels. They cap delta-9-THC at 10 milligrams per piece for edibles, and 1,000 milligrams per container for extracts and topicals. Dried cannabis flower and pre-rolled joints have no THC cap, but must disclose the THC level on their labels.

Other intoxicating cannabinoids — like delta-8-THC — are not regulated the same way. Some producers use these other cannabinoids to get around delta-9 limits to make their products more potent.

In 2023, Health Canada issued guidance warning against this practice, noting it could lead to inspections and regulatory action. Its guidance is not legally binding.

“Good weed”

Dr. Oyedeji Ayonrinde, a professor of psychiatry and psychology at Queen’s University, says “good weed” used to mean a product did not contain pesticides or contaminants. Now, it often means a product is high-THC — reinforcing the risky idea that stronger is better.

“We would say, Oh, man, that guy’s got good weed,’ because it’s 30 per cent [THC],” he said.

Today, THC levels average about 25 per cent — up from about four per cent in the 1960s. But some products go as high as 80 or 90 per cent THC.

“That’s ‘the good stuff,’” said Ayonrinde, referring to how consumers view products with these elevated levels of THC.

“One of the major [health] risk factors is the use of cannabis with higher than 10 per cent THC,” said Dr. Daniel Myran, a physician and Canada Research Chair at the University of Ottawa.

Myran led three Canadian studies this year linking heavy cannabis use to health risks such as schizophrenia, dementia and early death.

Chris Blair, a Canadian originally from Jamaica, says the cannabis he once smoked — natural, Jamaican, homegrown weed known as “sess” — was much milder than what is available through Ontario dispensaries today.

“We grew it, it was natural … the regular Mary Jane sess,” he said. “And then times changed … the sess was pushed to almost become the hydro[ponic] type of thing.”

Hydroponic growing methods produce more potent cannabis with higher THC levels. Blair says he could no longer go back to Jamaican sess, because he had built up a tolerance to it.

“Unfortunately, going back to sess was not the same, because it wasn’t the same high or same strength,” he said.

“Back when [I was] smoking [Jamaican sess] … I’d finished that spliff and we were ready to go hang out, we’re ready to party.

“Nowadays, after you smoke you’re mashed and you’re not doing anything.”

Greening out

Ayonrinde says higher THC levels can alter how the brain’s dopamine receptors work, which may induce paranoia.

“Being out of touch with reality, auditory hallucinogens, delusional thoughts, disorganized thinking — that’s part of the mechanism pathway for the development of a severe and enduring mental illness [like] schizophrenia,” he said.

High THC can also worsen anxiety, disrupt sleep, affect mood and trigger psychosis, he says. Other experts cited risks including cannabis use disorder, mental health issues, and dizziness or nausea — sometimes referred to as “greening out.”

Young people, whose brains are still developing until age 25, are most vulnerable to these harmful effects, Ayonrinde says.

During adolescence, the brain undergoes intense growth. “Think of the brain like a construction site,” he said. Frequent, high-dose THC use during this critical period can disrupt dopamine systems and increase the risk of building scaffolding for serious mental health conditions.

While some literature suggests that cannabidiol (CBD) — another major cannabinoid in most cannabis products — may act as a calming, non-psychoactive counterbalance to THC, Ayonrinde says this is only true at extremely high doses, around 6,000 mg.

Standard measurement

Experts say the diversity of cannabis products on the market is part of the challenge.

“When people say, ‘Weed helps me with my trauma,’ an example I often give is: cannabis is just like saying ‘dog’,” said Ayonrinde.

“What breed? Is it a chihuahua or a rottweiler or a great dane? Because without knowing exactly the THC, CBD … what are you talking about?

“There’s no single cannabis.”

Cannabis products lack clear dosage guidelines, and Ayonrinde says marketing messages push consumers to opt for high potency options.

Ruth Ross, a professor of pharmacology and toxicology at the University of Toronto, would like Canada to adopt a standard unit of measurement for THC levels, so consumers could easily understand what one unit means.

“Say a unit was one milligram; they could multiply that up — it’s easy math,” she said.

Myran agrees. “The way we sell alcohol in this country is not set up so that you pay the same amount for a litre of wine as you do for a litre of vodka,” said Myran.

“You have a minimum price per unit of ethanol … and there’s a really compelling reason to price cannabis according to its THC content … [to] financially discourage people from always moving to the highest potency THC products.”

Ross says there is also a need for more current cannabis research. Most cannabis research evaluates the effects of cannabis products with much lower THC levels than those seen on the market today. Long-term health effects can take decades to appear — similar to tobacco.

“Some of [the health harms] might emerge over many, many years, and we don’t know what those will be until data comes in,” she said.

Quebec’s approach

Ross points to Quebec as a unique model in cannabis regulation. It is the only province that caps THC potency and tightly controls how cannabis can be marketed. For example, edibles resembling candy or desserts are prohibited.

Jutras-Aswad, of the Université de Montréal, says overly strict rules can drive some consumers — especially those younger than the province’s legal age of 21 — to the black market.

Still, he says Quebec’s model offers benefits, including greater control over sales and a public health approach focused on harm reduction rather than profit.

Under Quebec’s Cannabis Regulation Act, the Société québécoise du cannabis (SQDC) is the only authorized cannabis retailer in the province.

SQDC employees are trained to offer science-based information, connect consumers with support services and promote safer use.

Researchers in Ontario are now studying how Quebec’s stricter THC limits may be affecting cannabis-related harms compared to other provinces.

“That’s going to be a really interesting within-Canada experiment,” said Ross.

Myran recommends adopting Quebec’s 30 per cent THC caps nationwide.

He also recommends better product labelling requirements and a pricing model that sets a minimum price per unit of THC — to discourage the purchase of high-potency products.

In a 2023 op-ed, Ross argued provinces should fund cannabis research to guide policy and public health.

In it, she notes that Quebec reinvested all $95 million of its 2022 revenue from cannabis sales into prevention and research. By contrast, Ontario set aside just 0.1% of its $170 million in cannabis revenue for a Social Impact Fund that has no clear public health focus.

“Canada can do so much better. We have world experts in cannabis research from coast-to-coast, and we are uniquely positioned to have high-quality, well-funded research on its medical use and potential harms,” she wrote.

“Five years from now, will we be dealing with major public health challenges that could have been avoided?”

This article was produced through the Breaking Needles Fellowship Program, which provided a grant to Canadian Affairs, a digital media outlet, to fund journalism exploring addiction and crime in Canada. Articles produced through the Fellowship are co-published by Break The Needle and Canadian Affairs.

The Bureau is a reader-supported publication.

To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Invite your friends and earn rewards

-

Business16 hours ago

Business16 hours agoOver $2B California Solar Plant Built To Last, Now Closing Over Inefficiency

-

espionage2 days ago

espionage2 days agoCanada Under Siege: Sparking a National Dialogue on Security and Corruption

-

Business15 hours ago

Business15 hours agoWEF has a plan to overhaul the global financial system by monetizing nature

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoGoogle Admits Biden White House Pressured Content Removal, Promises to Restore Banned YouTube Accounts

-

Business17 hours ago

Business17 hours agoThe Leaked Conversation at the heart of the federal Gun Buyback Boondoggle

-

Opinion15 hours ago

Opinion15 hours agoThe City of Red Deer’s financial mess – KPMG report outlines failure of council to control spending

-

International2 days ago

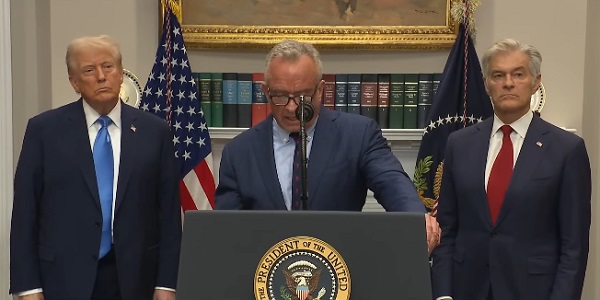

International2 days agoTrump says he won’t back down on Antifa terrorism designation

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoDepartment of Energy returning $13B climate agenda funding to taxpayers