Business

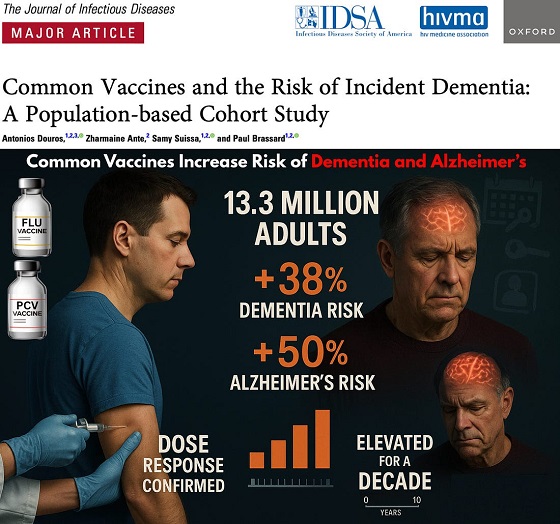

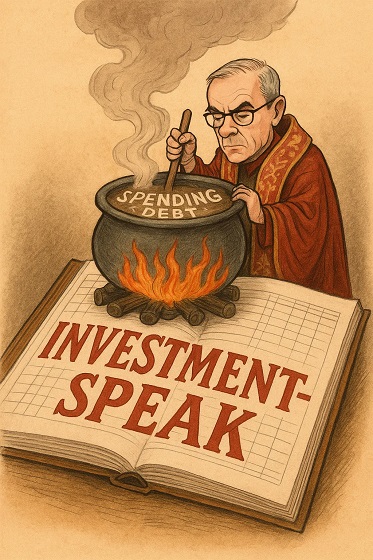

When Words Cook the Books: The Politics of ‘Investment-Speak’

The trick lies in the word “investment.” By separating “operational spending” from “capital investment,” Ottawa can now reclassify expenditures, moving them from one column to another without changing the underlying reality. A deficit remains a deficit.

Next week, Ottawa will table its first budget in nearly two years. The government has already told us what to expect. In October, the Department of Finance announced a new “Capital Budgeting Framework” that would allow Canada to “spend less so it can invest more.” The phrasing sounds prudent. It is not. It is a linguistic sleight of hand designed to obscure what the government is actually doing: spending more while pretending to exercise restraint.

The older meanings of the two words reveal the moral inversion. To spend, from the Latin dispendere, meant to weigh out and let go. It implied the careful release of what one possessed, whether money, time, or energy. In Old English and Middle English, to “spend” one’s life or strength was to pour it out, knowingly and finitely. There was gravity to the act; what was spent was gone. To invest, by contrast, came from the Latin investīre: to clothe or cover. Before it became a financial term, it referred to the ceremonial act of placing robes upon a monarch or knight, endowing them with office or honour. In its financial sense, to invest was to “clothe money” in a venture, expecting return. The first word carried finality; the second, expectancy. Spending ended a possession; investing disguised it in the promise of future gain.

From these roots, the moral difference is clear. Spending belongs to the household, measured, finite, and real. Investing belongs to the court, symbolic, ceremonial, and often self-flattering. When a government calls its spending “investment,” it does not change the transaction; it changes the costume.

The gradual adoption of this vocabulary by governments is an old habit dressed as innovation. For two decades, Ottawa has been learning to speak the language of investment as disguise. Budgets that once tabulated “program spending” now announce “investments in Canadians.” Under the Trudeau governments, tax credits and subsidies were cast as “investments in innovation.” The Canada Infrastructure Bank was sold as “leveraging private investment” rather than public debt. Even emergency COVID programs were justified as “investing in recovery.” The word became a universal solvent, dissolving distinctions between cost, borrowing, and speculation.

This year’s government has merely made the trend official. In October, the Department of Finance released Modernizing Canada’s Budgeting Approach, explaining that the new Capital Budgeting Framework would “distinguish day-to-day operational spending from capital investment.” The document asserts that this will “guide decisions and help prioritize. The trick lies in the word “investment.” By separating “operational spending” from “capital investment,” Ottawa can now reclassify expenditures, moving them from one column to another without changing the underlying reality. A deficit remains a deficit. Borrowed money is still borrowed. But call it investment, and suddenly it carries the glow of foresight and responsibility. The government plans to balance its operating budget while continuing to borrow for capital projects. The ledger will grow, but the language will comfort.

This is not merely bad accounting. It is a deliberate corruption of language in service of political evasion. And it reveals something deeper about how modern governments govern: not through honest argument but through the manipulation of words.

Ottawa has been perfecting this costume for two decades. Budgets that once listed “program spending” now announce “investments in Canadians.” Tax credits became “investments in innovation.” The Canada Infrastructure Bank was sold as “leveraging private investment,” not public debt. COVID emergency programs were justified as “investing in recovery.” The word became a universal solvent, dissolving the distinction between cost, borrowing, and speculation.

This year’s framework makes the habit official. The October document from Finance Canada promises that the new approach will “guide decisions and help prioritize investments that generate long-term benefits for Canadians, such as major projects, housing, clean energy, and infrastructure.” The tone is managerial and assured. The assumption goes unexamined: that one can divide the public purse into virtuous investment and wasteful spending, and that the government possesses the wisdom to know the difference.

Haultain Research is a reader-supported publication.

To receive new posts and support our work, consider becoming a donor or a paid subscriber.

The Prime Minister echoed the line in his own announcement: “Budget 2025 will set out our plan to spend less so we can invest more in Canada’s long-term growth.” Read carefully, the statement reveals its own dishonesty. To “spend less” no longer means reducing outlays. It means shifting expenditures into a different category where they escape the stigma of cost. The government intends to continue borrowing, but it will refer to that borrowing by a supposedly more respectable name.

The definition of capital investment is conveniently broad. It includes tax credits, corporate subsidies, and nearly any policy “that contributes to capital formation.” The Fraser Institute and others have warned that this expansiveness allows Ottawa to reclassify politically favored programs as investment, inflating the appearance of fiscal discipline while reducing transparency. A deficit becomes a “generational investment.” A subsidy becomes a “partnership.” Waste is rebranded as “capacity-building.” The language does the work that policy cannot.

Recent history exposes the fraud. Consider the electric vehicle battery subsidies, heralded as “historic investments” in the green economy. Tens of billions were promised. Projects have stalled, been postponed, or quietly abandoned. The so-called green slush fund, officially presented as an investment vehicle for sustainable innovation, turned out to be a network of cronyism and waste. These, too, were dressed as investments. When their failures emerged, the language remained untouched, as though incompetence and corruption could not breach the sanctity of the term.

The alchemy works because language shapes perception faster than arithmetic. “Investment” suggests prudence and reward. “Spending” suggests indulgence and loss. Citizens hear that the government is “investing in Canadians” and imagine return, not depletion. The moral weight of the word does the political work. Accountability fades behind aspiration.

There is a deeper danger here. Words like spend and cost belong to the vocabulary of limits. They remind us that government operates with other people’s money. Invest, as politicians now use it, belongs to the vocabulary of boundless promise. It implies benevolence without constraint, as though the state were a benefactor rather than a borrower. When the government claims to “invest in Canadians,” it implies ownership of the very people whose money it spends. The inversion of subject and object is telling. It reveals the paternalism at the heart of modern technocracy.

George Orwell wrote that political language “is designed to make lies sound truthful and murder respectable.” He understood that the corruption of speech precedes the corruption of thought. When a government renames its spending as investment, it is not simply misdescribing an accounting category. It is reshaping the citizen’s perception of what government may do. If all spending is investment, then any limit on it seems stingy, even immoral. The citizen becomes debtor to a future defined by the state.

The deceit is subtle. No one disputes that bridges or power grids can be sound investments. The deceit lies in the implication that all government activity now yields return, that every expense is productive, every grant visionary. By this logic, no spending is considered waste and no deficit is deemed reckless, as long as it is labelled as an investment. The language abolishes the distinction between consumption and creation, between present sacrifice and future gain. In doing so, it abolishes prudence itself.

Prudence, in the older sense, is not caution for its own sake. It is moral realism: the recognition that resources are finite and choices have costs. The new investment rhetoric invites the opposite illusion. Money, once moralized as investment, appears to carry no weight of trade-off. Ottawa can clothe profligacy in the robes of responsibility. The government that promises to “spend less and invest more” is like a man claiming to drink less whiskey by pouring it into crystal.

The cost of this linguistic vanity is not only fiscal. It corrodes public trust. Citizens sense the dissonance. Deficits widen, taxes climb, promises multiply. When language becomes a substitute for honesty, cynicism follows. A people that cannot trust its government’s words cannot trust its numbers.

The remedy is simple, though seldom easy: call things by their names. Spending is spending, whether on roads, welfare, or research. Some are wise, some are foolish. But none becomes virtuous by relabeling. The duty of government is not to invent euphemisms but to justify expenditures plainly and bear the consequences. That is what accountability means.

Roger Scruton observed that conservatism, properly understood, is “the politics of the tried and tested against the politics of experiment.” In fiscal speech, that means preferring accuracy to allure. A government confident in its stewardship would not fear plain-spoken spending. Only one uneasy with its own excess needs the comfort of investment.

Ottawa’s linguistic reform is therefore not a matter of diction. It is an attempt to alter reality through language, to convert liability into virtue by decree. The danger is that citizens, lulled by investment-speak, will cease to notice the arithmetic beneath. The numbers will grow; the language will glow. By the time the robe is lifted, the treasury will be bare.

That is not a forecast. It is a warning. When governments clothe waste in the garments of investment, they are not modernizing accounting. They are modernizing deceit.

We are grateful that you’re reading an article from Haultain Research.

For the full experience, and to help us bring you more quality research and commentary,

Business

Ottawa Pretends To Pivot But Keeps Spending Like Trudeau

From the Frontier Centre for Public Policy

New script, same budget playbook. Nothing in the Carney budget breaks from the Trudeau years

Prime Minister Mark Carney’s first budget talks reform but delivers the same failed spending habits that defined the Trudeau years.

While speaking in the language of productivity, infrastructure and capital formation, the diction of grown-up economics, it still follows the same spending path that has driven federal budgets for years. The message sounds new, but the behaviour is unchanged.

Time will tell, to be fair, but it feels like more rhetoric, and we have seen this rhetoric lead to nothing before.

The government insists it has found a new path, one where public investment leads private growth. That sounds bold. However, it is more a rebranding than a reform. It is a shift in vocabulary, not in discipline. The government’s assumptions demand trust, not proof, and the budget offers little of the latter.

Former prime ministers Jean Chrétien and Paul Martin did not flirt with restraint; they executed it. Their budget cuts were deep, restored credibility, and revived Canada’s fiscal health when it was most needed. Ottawa shrank so the country could grow. Budget 2025 tries to invoke their spirit but not their actions. The contrast shows how far this budget falls short of real reform.

Former prime minister Stephen Harper, by contrast, treated balanced budgets as policy and principle. Even during the global financial crisis, his government used stimulus as a bridge, not a way of life. It cut taxes widely and consistently, limited public service growth and placed the long-term burden on restraint rather than rhetoric. Carney’s budget nods toward Harper’s focus on productivity and capital assets, yet it rejects the tax relief and spending controls that made his budgets coherent.

Then there is Justin Trudeau, the high tide of redistribution, vacuous identity politics and deficit-as-virtue posturing. Ottawa expanded into an ideological planner for everything, including housing, climate, childcare, inclusion portfolios and every new identity category.

The federal government’s latest budget is the first hint of retreat from that style. The identity program fireworks are dimmer, though they have not disappeared. The social policy boosterism is quieter. Perhaps fiscal gravity has begun to whisper in the prime minister’s ear.

However, one cannot confuse tone for transformation.

Spending still rises at a pace the government cannot justify. Deficits have grown. The new fiscal anchor, which measures only day-to-day spending and omits capital projects and interest costs, allows Ottawa to present a balanced budget while still adding to the deficit. The budget relies on the hopeful assumption that Ottawa’s capital spending will attract private investment on a scale economists politely describe as ambitious.

The housing file illustrates the contradiction. New funding for the construction of purpose-built rentals and a larger federal role in modular and subsidized housing builds announced in the budget is presented as a productivity measure, yet continues the Trudeau-era instinct to centralize housing policy rather than fix the levers that matter. Permitting delays, zoning rigidity, municipal approvals and labour shortages continue to slow actual construction. These barriers fall under provincial and municipal control, meaning federal spending cannot accelerate construction unless those governments change their rules. The example shows how federal spending avoids the real obstacles to growth.

Defence spending tells the same story. Budget 2025 offers incremental funding and some procurement gestures, but it avoids the core problem: Canada’s procurement system is broken. Delays stretch across decades. Projects become obsolete before contracts are signed. The system cannot buy a ship, an aircraft or an armoured vehicle without cost overruns and missed timelines. The money flows, but the forces do not get the equipment they need.

Most importantly, the structural problems remain untouched: no regulatory reform for major projects, no tax-competitiveness agenda and no strategy for shrinking a federal bureaucracy that has grown faster than the economy it governs. Ottawa presides over a low-productivity country but insists that a new accounting framework will solve what decades of overregulation and policy clutter have created. The budget avoids the hard decisions that make countries more productive.

From an Alberta vantage, the pivot is welcome but inadequate. The economy that pays for Confederation receives more rhetorical respect, yet the same regulatory thicket that blocks pipelines and mines remains intact. The government praises capital formation but still undermines the key sectors that generate it.

Budget 2025 tries to walk like Chrétien and talk like Harper while spending like Trudeau. That is not a transformation. It is a costume change. The country needed a budget that prioritized growth rooted in tangible assets and real productivity. What it got instead is a rhetorical turn without the courage to cut, streamline or reform.

Canada does not require a new budgeting vocabulary. It requires a government willing to govern in the country’s best interests.

Marco Navarro-Genie is vice-president of research at the Frontier Centre for Public Policy and co-author with Barry Cooper of Canada’s COVID: The Story of a Pandemic Moral Panic (2023).

Business

COP30 finally admits what resource workers already knew: prosperity and lower emissions must go hand in hand

From Resource Works

What a difference a few weeks make

Finally, the Conference of the Parties to the UN climate convention (COP30) adopted a pragmatic tone that will appeal to the working class. Too bad it took thirty meetings. Pragmatism produces results, not missed targets.

We should not have been surprised. Influential figures like Bill Gates and Canadian-Venezuelan analyst Quico Toro, who have long argued that efforts to reduce CO₂ should focus more on technology and prosperity, and less on energy consumption and declining growth, have gained ground.

In the World Energy Outlook 2025, prepared by the International Energy Agency for COP30, you can see that many of the views held by the people above had already gone mainstream before the conference started.

The World Energy Outlook 2025 lays out three scenarios: Current Policies (CPS), Stated Policies (STEPS), and Net Zero Emissions by 2050 (NZE). In WEO 2025, all three scenarios reflect longer timelines for the decline of fossil fuels than in earlier editions, and the NZE pathway explicitly states that major technological breakthroughs will be required.

Unfortunately, many potential technologies are adamantly opposed by the loudest groups within the Climate Change Movement because they are not perfect. Even some continue to oppose nuclear power, one of the few proven sources of large-scale, zero-carbon, firm electricity.

Another noteworthy standout in WEO 2025 was the strong recognition that energy security, costs, and supply chains are now the primary considerations in determining each country’s energy mix.

What all this means is we are breaking away from emotionally charged, fear-based policies and rhetoric and moving toward a practical “let’s do things better” approach.

For 30 years, the radical leadership of the environmental movement has focused on what we should stop doing and on sacrificing prosperity. Essentially, what has been going on is an attack on working people in the industrialized and developing world.

Today, workers in the developed world are so anxious that many are losing faith in democratic institutions. Meanwhile, people in the emerging and developing world see light at the end of the tunnel and are determined to industrialize.

Clearly, it is time to merge the fight to lower CO₂ emissions with prosperity. “Let’s do things better” captures the history of human progress and resonates with working people today.

What does it take for longer, healthier, safer, and more sustainable lives? It takes the pragmatism of workers. They spend their lives striving to improve workplace safety, to develop tools that enable them to perform tasks more effectively with less physical effort, to earn higher pay, to produce more food with less land, and to preserve their opportunity to continue working.

Resource workers have felt under attack and are humiliated when celebrities fly in on a helicopter to denigrate their work and make references to the virtues of small-plot gardening, or politicians who tell them to go back to school for “jobs of the future”, only to find themselves in low-paying service jobs.

As the COP30 discussion indicates, we have reached a turning point. It is time to focus on doing what needs to be done, but doing it better. It is time to stop banning activities entirely as though circumstances and technology never change. Demanding perfection hides what is possible, slows progress and, in some cases, stops it altogether.

Bill Gates’ memo to COP30 points to the turn in the road:

“We should measure success by our impact on human welfare more than our impact on the global temperature, and our success relies on putting energy, health, and agriculture at the centre of our strategies.”

Gates also makes a point that will resonate with working people: “Using more energy is a good thing because it is closely correlated with economic growth.” Ironically, a statement made by a billionaire resonates with working people more than does the message of many climate activists.

The work at the Port of Prince Rupert comes to mind, given its growing role in supplying cleaner cooking and heating fuels, when we are reminded that 2 billion people worldwide cook and/or heat their homes with highly polluting open fires (wood, charcoal, dung, agricultural waste).

Persuasion published Quico Toro’s essay on November 13, 2025, which speaks another truth.

“COP imagines these emissions as something a country’s government can set, like the dial on a thermostat. But emissions are more like GDP: the outcome of a complex process that politicians would like to be able to control, but do not actually control.”

I am feeling more secure about the future here in Canada and BC, as governments, First Nations and the public are leaning into climate and economic pragmatism.

There will be hard discussions and uncomfortable trade-offs. Past decisions need to be re-examined in good faith. Do they meet today’s demands? Are we doing what needs to be done better? Is it the right move for today’s youth and future generations? Will we bring back the hope and opportunity of a growing middle class?

Nobody, not the Liberal government, the BC NDP government, First Nations, none of us would have predicted the world we are facing today, where our economy and sovereignty are challenged.

Today, oil, natural gas, and critical minerals, not one or two but all three, are the financial backstop Canada needs, as we rebuild the economy and secure our sovereignty.

Look West: Jobs and Prosperity for Stronger BC and Canada is as much of an admission that we are falling behind as it is a call to action. Success will take billions of dollars, the exact amount unknown.

But what we do know is that oil, gas, and critical minerals generate the most public revenue, the highest incomes, and are our most significant exports. They are Canada’s bank and comparative advantage. They will provide the cash flow needed to get it done.

Not maximizing oil production and exports is fighting with both hands tied behind our back. We all know it; now we need to focus on doing it better because circumstances have changed dramatically.

Jim Rushton is a 46-year veteran of BC’s resource and transportation sectors, with experience in union representation, economic development, and terminal management.

Resource Works News

-

Great Reset2 days ago

Great Reset2 days agoViral TikTok video shows 7-year-old cuddling great-grandfather before he’s euthanized

-

Daily Caller2 days ago

Daily Caller2 days agoChinese Billionaire Tried To Build US-Born Baby Empire As Overseas Elites Turn To American Surrogates

-

Alberta2 days ago

Alberta2 days agoSchools should go back to basics to mitigate effects of AI

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoMajor tax changes in 2026: Report

-

International2 days ago

International2 days agoTwo states designate Muslim group as terrorist

-

Digital ID1 day ago

Digital ID1 day agoCanada releases new digital ID app for personal documents despite privacy concerns

-

Censorship Industrial Complex2 days ago

Censorship Industrial Complex2 days agoDeath by a thousand clicks – government censorship of Canada’s internet

-

Bruce Dowbiggin1 day ago

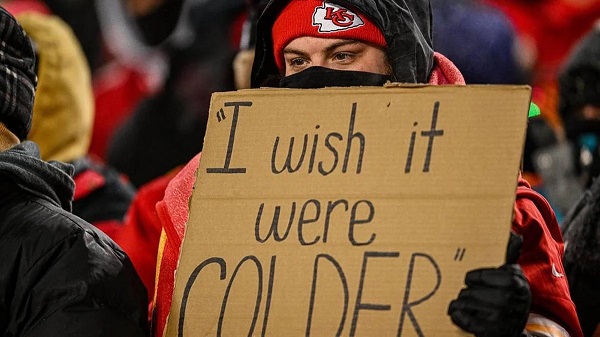

Bruce Dowbiggin1 day agoNFL Ice Bowls Turn Down The Thermostat on Climate Change Hysteria