Fraser Institute

U.S. election should focus or what works and what doesn’t work

From the Fraser Institute

As Republicans and Democrats make their final pitch to voters, they’ve converged on some common themes. Kamala Harris wants to regulate the price of food. Donald Trump wants to regulate the price of credit. Harris wants the tax code to favour the 2.5 per cent of workers who earn tips. So does Trump. Harris wants the government to steer more labour and capital into manufacturing. And so does Trump.

With each of these proposals, the candidates think the United States would be better off if the government made more economic decisions and—by implication—if individual citizens made fewer economic decisions. Both should pay closer attention to Zimbabwe. Yes, Zimbabwe.

Why does a country with abundant natural resources, rich culture and unparalleled beauty have one-sixth the average income of neighbouring Botswana? While we’re at it, why do twice as many children die in infancy in Azerbaijan as across the border in Georgia? Why do Hungarians work 20 per cent longer than their Austrian neighbours but earn 45 per cent less? Why is extreme poverty 200 times more common in Laos than across the Mekong River in Thailand?

Or how about this one: Why were more than one-quarter of Estonians formerly exposed to dangerous levels of air pollution when the country was socialist while today nearly every Estonian breathes clean air in what is ranked the cleanest country in the world.

These are anecdotes. However, the plural of anecdote is data, and through careful and systematic study of the data, we can learn what works and what doesn’t. Unfortunately, the populist economic policies in vogue among Democrats and Republicans do not work.

What does work is economic freedom.

Economic freedoms are a subset of human freedoms. When people have more economic freedom, they are allowed to make more of their own economic choices—choices about work, about buying and selling goods and services, about acquiring and using property, and about forming contracts with others.

For nearly 30 years, the Fraser Institute has been measuring economic freedom across countries. On one hand, governments can stop people from making their own economic choices through taxes, regulations, barriers to trade and manipulation of the value of money (see the proposals of Harris and Trump above). On the other hand, governments can enable individual economic choice by protecting people and their property.

The index published in Fraser’s annual Economic Freedom of the World report incorporates 45 indicators to measure how governments either prevent or enable individual economic choice. The result reveals the degree of economic freedom in 165 countries and territories worldwide, with data going back to 1970.

According to the latest report, comparatively wealthy Botswanans rank 84 places ahead of Zimbabweans in terms of the economic freedom their government permits them. Georgians rank 107 places ahead of Azerbaijanis, Thais rank 60 places ahead of Laotians, and Austrians are 32 places ahead of Hungarians.

The benefits of economic freedom go far beyond anecdotes and rankings. As Estonia—once one of the least economically free places in the world and now among the freest—dramatically shows, freer countries tend not only to be more prosperous but greener and healthier.

In fact, economists and other social scientists have conducted nearly 1,000 studies using the index to assess the effect of economic freedom on different aspects of human wellbeing. Their statistical comparisons include hundreds and sometimes thousands of data points and carefully control for other factors like geography, natural resources and disease environment.

Their results overwhelmingly support the idea that when people are permitted more economic freedom, they prosper. Those who live in freer places enjoy higher and faster-growing incomes, better health, longer life, cleaner environments, more tolerance, less violence, lower infant mortality and less poverty.

Economic freedom isn’t the only thing that matters for prosperity. Research suggests that culture and geography matter as well. While policymakers can’t always change people’s attitudes or move mountains, they can permit their citizens more economic freedom. If more did so, more people would enjoy the living standards of Botswana or Estonia and fewer people would be stuck in poverty.

As for the U.S., it remains relatively free and prosperous. Whatever its problems, decades of research cast doubt on the notion that America would be better off with policies that chip away at the ability of Americans to make their own economic choices.

Author:

Agriculture

Canada’s air quality among the best in the world

From the Fraser Institute

By Annika Segelhorst and Elmira Aliakbari

Canadians care about the environment and breathing clean air. In 2023, the share of Canadians concerned about the state of outdoor air quality was 7 in 10, according to survey results from Abacus Data. Yet Canada outperforms most comparable high-income countries on air quality, suggesting a gap between public perception and empirical reality. Overall, Canada ranks 8th for air quality among 31 high-income countries, according to our recent study published by the Fraser Institute.

A key determinant of air quality is the presence of tiny solid particles and liquid droplets floating in the air, known as particulates. The smallest of these particles, known as fine particulate matter, are especially hazardous, as they can penetrate deep into a person’s lungs, enter the blood stream and harm our health.

Exposure to fine particulate matter stems from both natural and human sources. Natural events such as wildfires, dust storms and volcanic eruptions can release particles into the air that can travel thousands of kilometres. Other sources of particulate pollution originate from human activities such as the combustion of fossil fuels in automobiles and during industrial processes.

The World Health Organization (WHO) and the Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment (CCME) publish air quality guidelines related to health, which we used to measure and rank 31 high-income countries on air quality.

Using data from 2022 (the latest year of consistently available data), our study assessed air quality based on three measures related to particulate pollution: (1) average exposure, (2) share of the population at risk, and (3) estimated health impacts.

The first measure, average exposure, reflects the average level of outdoor particle pollution people are exposed to over a year. Among 31 high-income countries, Canadians had the 5th-lowest average exposure to particulate pollution.

Next, the study considered the proportion of each country’s population that experienced an annual average level of fine particle pollution greater than the WHO’s air quality guideline. Only 2 per cent of Canadians were exposed to fine particle pollution levels exceeding the WHO guideline for annual exposure, ranking 9th of 31 countries. In other words, 98 per cent of Canadians were not exposed to fine particulate pollution levels exceeding health guidelines.

Finally, the study reviewed estimates of illness and mortality associated with fine particle pollution in each country. Canada had the fifth-lowest estimated death and illness burden due to fine particle pollution.

Taken together, the results show that Canada stands out as a global leader on clean air, ranking 8th overall for air quality among high-income countries.

Canada’s record underscores both the progress made in achieving cleaner air and the quality of life our clean air supports.

Economy

Affordable housing out of reach everywhere in Canada

From the Fraser Institute

By Steven Globerman, Joel Emes and Austin Thompson

According to our new study, in 2023 (the latest year of comparable data), typical homes on the market were unaffordable for families earning the local median income in every major Canadian city

The dream of homeownership is alive, but not well. Nearly nine in ten young Canadians (aged 18-29) aspire to own a home—but share a similar worry about the current state of housing in Canada.

Of course, those worries are justified. According to our new study, in 2023 (the latest year of comparable data), typical homes on the market were unaffordable for families earning the local median income in every major Canadian city. It’s not just Vancouver and Toronto—housing affordability has eroded nationwide.

Aspiring homeowners face two distinct challenges—saving enough for a downpayment and keeping up with mortgage payments. Both have become harder in recent years.

For example, in 2014, across 36 of Canada’s largest cities, a 20 per cent downpayment for a typical home—detached house, townhouse, condo—cost the equivalent of 14.1 months (on average) of after-tax income for families earning the median income. By 2023, that figure had grown to 22.0 months—a 56 per cent increase. During the same period for those same families, a mortgage payment for a typical home increased (as a share of after-tax incomes) from 29.9 per cent to 56.6 per cent.

No major city has been spared. Between 2014 and 2023, the price of a typical home rose faster than the growth of median after-tax family income in 32 out of 36 of Canada’s largest cities. And in all 36 cities, the monthly mortgage payment on a typical home grew (again, as a share of median after-tax family income), reflecting rising house prices and higher mortgage rates.

While the housing affordability crisis is national in scope, the challenge differs between cities.

In 2023, a median-income-earning family in Fredericton, the most affordable large city for homeownership in Canada, had save the equivalent of 10.6 months of after-tax income ($56,240) for a 20 per cent downpayment on a typical home—and the monthly mortgage payment ($1,445) required 27.2 per cent of that family’s after-tax income. Meanwhile, a median-income-earning family in Vancouver, Canada’s least affordable city, had to spend the equivalent of 43.7 months of after-tax income ($235,520) for a 20 per cent downpayment on a typical home with a monthly mortgage ($6,052) that required 112.3 per cent of its after-tax income—a financial impossibility unless the family could rely on support from family or friends.

The financial barriers to homeownership are clearly greater in Vancouver. But, crucially, neither city is truly “affordable.” In Fredericton and Vancouver, as in every other major Canadian city, buying a typical home with the median income produces a debt burden beyond what’s advisable. Recent house price declines in cities such as Vancouver and Toronto have provided some relief, but homeownership remains far beyond the reach of many families—and a sharp slowdown in homebuilding threatens to limit further gains in affordability.

For families priced out of homeownership, renting doesn’t offer much relief, as rent affordability has also declined in nearly every city. In 2014, rental rates for the median-priced rental unit required 19.8 per cent of median after-tax family income, on average across major cities. By 2023, that figure had risen to 23.5 per cent. And in the least affordable cities for renters, Toronto and Vancouver, a median-priced rental required more than 30 per cent of median after-tax family income. That’s a heavy burden for Canada’s renters who typically earn less than homeowners. It’s also an added financial barrier to homeownership— many Canadian families rent for years before buying their first home, and higher rents make it harder to save for a downpayment.

In light of these realities, Canadians should ask—why have house prices and rental rates outpaced income growth?

Poor public policy has played a key role. Local regulations, lengthy municipal approval processes, and costly taxes and fees all combine to hinder housing development. And the federal government allowed a historic surge in immigration that greatly outpaced new home construction. It’s simple supply and demand—when more people chase a limited (and restricted) supply of homes, prices rise. Meanwhile, after-tax incomes aren’t keeping pace, as government policies that discourage investment and economic growth also discourage wage growth.

Canadians still want to own homes, but a decade of deteriorating affordability has made that a distant prospect for many families. Reversing the trend will require accelerated homebuilding, better-paced immigration and policies that grow wages while limiting tax bills for Canadians—changes governments routinely promise but rarely deliver.

-

Bruce Dowbiggin3 hours ago

Bruce Dowbiggin3 hours agoWayne Gretzky’s Terrible, Awful Week.. And Soccer/ Football.

-

espionage6 hours ago

espionage6 hours agoWestern Campuses Help Build China’s Digital Dragnet With U.S. Tax Funds, Study Warns

-

Agriculture2 hours ago

Agriculture2 hours agoCanada’s air quality among the best in the world

-

Business4 hours ago

Business4 hours agoCanada invests $34 million in Chinese drones now considered to be ‘high security risks’

-

Economy5 hours ago

Economy5 hours agoAffordable housing out of reach everywhere in Canada

-

Business2 days ago

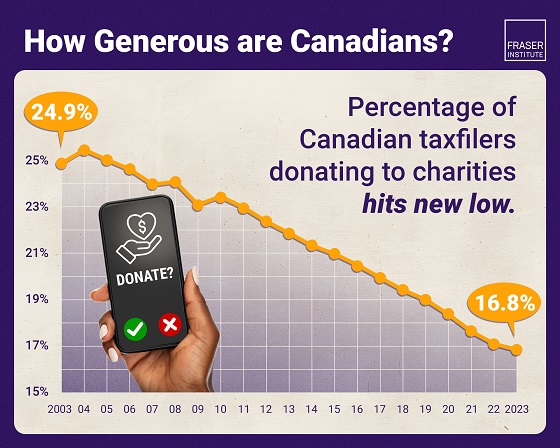

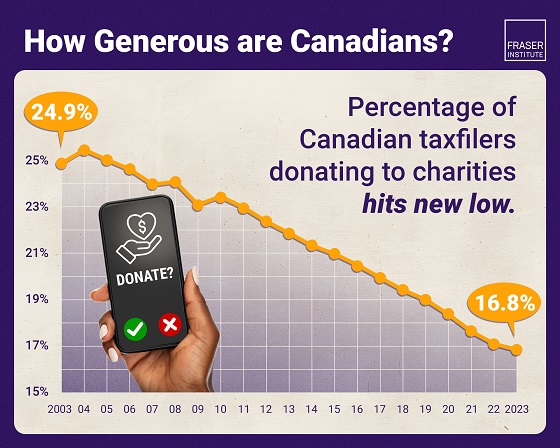

Business2 days agoAlbertans give most on average but Canadian generosity hits lowest point in 20 years

-

Fraser Institute1 day ago

Fraser Institute1 day agoClaims about ‘unmarked graves’ don’t withstand scrutiny

-

Bruce Dowbiggin2 days ago

Bruce Dowbiggin2 days agoCarney Hears A Who: Here Comes The Grinch