Economy

Trudeau punishing Canadians for surviving cold winter

From the Canadian Taxpayers Federation

Author: Franco Terrazzano

Millions of Canadians are keeping an anxious eye on their thermostats, praying the power stays on and bracing for carbon-taxed heat bills to arrive.

A frigid winter cold snap delivered daytime temperatures in the minus thirties with overnight windchills of more than minus 50 in parts of Canada. Natural gas furnaces are running around the clock, keeping families from freezing and water pipes from bursting.

The situation got scary Saturday when an Alberta-wide alarm blared across smartphones, TVs and radios. The province warned the power grid was maxing out and rolling blackouts were about to hit.

Alberta Premier Danielle Smith took to social media imploring Albertans to turn off their lights, stop using appliances and hunker down to save the power grid from blacking out. Saskatchewan Premier Scott Moe tagged in, announcing his province was sending 153 megawatts to Alberta.

When it’s minus 40, running the furnace isn’t a luxury, it’s a necessity. And yet, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau is punishing Canadians with a carbon tax for the sin of staying warm and staying alive in winter.

The federal carbon tax is currently set at $65 per tonne, costing 12 cents per cubic meter of natural gas and 10 cents per litre of propane. An average Canadian home uses about 2,385 cubic metres of natural gas per year, so the carbon tax will cost them about $300 extra to heat their home.

Even after the rebates, average families will be out hundreds of dollars this year because of the higher heating bills, gas prices, inflation and the economic damage that comes with the carbon tax, according to the Parliamentary Budget Officer.

But the Trudeau government isn’t done. On April 1, the carbon tax is going up to $80 per tonne. That will cost 15 cents per cubic metre of natural gas.

In fact, Trudeau plans to crank up his carbon tax every year. Over the next three years, Trudeau’s carbon tax will cost the average family $1,100 on natural gas alone.

Canada is a cold place. Keeping the heat on isn’t a luxury, it’s a necessity. And Trudeau’s carbon tax punishes families who need to stay warm during the winter months. Even worse, Trudeau knows the carbon tax makes it more expensive for families to stay warm.

“We are putting more money back in your pocket and making it easier for you to find affordable, long-term solutions to heat your home,” Trudeau said, when he removed the carbon tax from home heating oil for three years.

This was an admission of an obvious reality: the carbon tax makes life more expensive. Otherwise, why would Trudeau take the carbon tax off a form of heating energy?

Trudeau’s carbon tax-carve out was a political ploy to keep his Atlantic MPs from revolting while support for the Liberals plummeted in their typical stronghold.

While many Atlantic Canadians use heating oil, 97 per cent of Canadian families use other forms of energy, like natural gas or propane, and won’t get any relief from the feds this winter.

Even in Atlantic Canada, 77 per cent of people in the region want carbon tax relief for all Canadians this winter, according to a Leger poll commission by the Canadian Taxpayers Federation. Provincial politicians of all stripes have demanded the feds take the carbon tax off everyone’s heating bill.

That’s because staying warm isn’t a partisan issue. All Canadians need to heat their home. And we shouldn’t be punished with a tax just to survive the winter.

Trudeau should completely scrap his carbon tax. But at the very least he should extend the same relief he provided to Atlantic Canadians and take the carbon tax off everyone’s home heating bill.

Business

Fuelled by federalism—America’s economically freest states come out on top

From the Fraser Institute

Do economic rivalries between Texas and California or New York and Florida feel like yet another sign that America has become hopelessly divided? There’s a bright side to their disagreements, and a new ranking of economic freedom across the states helps explain why.

As a popular bumper sticker among economists proclaims: “I heart federalism (for the natural experiments).” In a federal system, states have wide latitude to set priorities and to choose their own strategies to achieve them. It’s messy, but informative.

New York and California, along with other states like New Mexico, have long pursued a government-centric approach to economic policy. They tax a lot. They spend a lot. Their governments employ a large fraction of the workforce and set a high minimum wage.

They aren’t socialist by any means; most property is still in private hands. Consumers, workers and businesses still make most of their own decisions. But these states control more resources than other states do through taxes and regulation, so their governments play a larger role in economic life.

At the other end of the spectrum, New Hampshire, Tennessee, Florida and South Dakota allow citizens to make more of their own economic choices, keep more of their own money, and set more of their own terms of trade and work.

They aren’t free-market utopias; they impose plenty of regulatory burdens. But they are economically freer than other states.

These two groups have, in other words, been experimenting with different approaches to economic policy. Does one approach lead to higher incomes or faster growth? Greater economic equality or more upward mobility? What about other aspects of a good society like tolerance, generosity, or life satisfaction?

For two decades now, we’ve had a handy tool to assess these questions: The Fraser Institute’s annual “Economic Freedom of North America” index uses 10 variables in three broad areas—government spending, taxation, and labor regulation—to assess the degree of economic freedom in each of the 50 states and the territory of Puerto Rico, as well as in Canadian provinces and Mexican states.

It’s an objective measurement that allows economists to take stock of federalism’s natural experiments. Independent scholars have done just that, having now conducted over 250 studies using the index. With careful statistical analyses that control for the important differences among states—possibly confounding factors such as geography, climate, and historical development—the vast majority of these studies associate greater economic freedom with greater prosperity.

In fact, freedom’s payoffs are astounding.

States with high and increasing levels of economic freedom tend to see higher incomes, more entrepreneurial activity and more net in-migration. Their people tend to experience greater income mobility, and more income growth at both the top and bottom of the income distribution. They have less poverty, less homelessness and lower levels of food insecurity. People there even seem to be more philanthropic, more tolerant and more satisfied with their lives.

New Hampshire, Tennessee, and South Dakota topped the latest edition of the report while Puerto Rico, New Mexico, and New York rounded out the bottom. New Mexico displaced New York as the least economically free state in the union for the first time in 20 years, but it had always been near the bottom.

The bigger stories are the major movers. The last 10 years’ worth of available data show South Carolina, Ohio, Wisconsin, Idaho, Iowa and Utah moving up at least 10 places. Arizona, Virginia, Nebraska, and Maryland have all slid down 10 spots.

Over that same decade, those states that were among the freest 25 per cent on average saw their populations grow nearly 18 times faster than those in the bottom 25 per cent. Statewide personal income grew nine times as fast.

Economic freedom isn’t a panacea. Nor is it the only thing that matters. Geography, culture, and even luck can influence a state’s prosperity. But while policymakers can’t move mountains or rewrite cultures, they can look at the data, heed the lessons of our federalist experiment, and permit their citizens more economic freedom.

Automotive

The $50 Billion Question: EVs Never Delivered What Ottawa Promised

Beware of government promises that arrive gift-wrapped in moral certainty.

The pattern repeats across the sector: subsidies extracted, production scaled back, workers laid off, taxpayers absorbing losses while executives collect bonuses and move on, and politicians pretend that it never happened. CBC isn’t asking Justin Trudeau, Katherine McKenna or Steven Guilbeault any questions about it. They are not asking Mark Carney.

Buy an electric vehicle, they said, and you will save the planet, no questions asked. Justin Trudeau and several of his ministers proclaimed it from podiums. Environmental activists, often cabinet members, chanted it at rallies. Automotive executives leveraged it to extract giant subsidies. For over a decade, the message never wavered: until $50 billion in public money disappeared into corporate failures, and the economic wreckage became impossible to ignore.

Prime Minister Mark Carney, himself a spokesperson for the doomsday culture, inherited the policy disaster from Trudeau and still clings to the wreckage. The 2026 EV sales target sits suspended, a grudging acknowledgment that reality refused to cooperate with radical predictions and Ottawa’s mandates. Yet the 2030 and 2035 targets remain federal law, monuments to a central-planning exercise that delivered the opposite of what it promised.

Their claims were never quite true. Electric vehicles were pure good. They were marketed as unconditionally cleaner than conventional cars, a transformation so obviously beneficial that questioning it invited accusations of climate denial. Government messaging suggested switching to an EV meant immediate environmental virtue. The nuance, the conditions, and the caveats were conveniently omitted from the government sales pitch that justified tens of billions of your money into subsidies for foreign EV manufacturing and corporate advancement.

The Reality Ottawa Is Hiding

Research documented the conditional nature of EV benefits for over a decade, yet Ottawa proceeded as if the complexity didn’t exist. Studies from China, where coal dominates electricity generation, showed as early as 2010 that EVs in coal-dependent regions had “very limited benefits” in reducing emissions compared to gasoline vehicles. In Northern China, where electricity generation is over 80% coal-based, EVs could produce lifecycle emissions comparable to or even higher than those of conventional cars. A 2015 Chinese study found that EVs generated lifecycle emissions that were only 18% lower than those of gasoline vehicles, compared to 40-70% reductions in regions with cleaner grids.

Volvo began publishing transparent lifecycle assessments for its first EV in 2019, making it the first major automaker to document the significant upfront emissions from battery production publicly. Their 2021 C40 Recharge report, released during the COP26 climate summit in Glasgow, revealed that manufacturing an EV produces 70% more emissions than building a comparable conventional vehicle. But there are no CBC reports about that. The Volvo report showed that an EV charged on a coal-heavy global grid required 68,000 to 110,000 miles of driving to break even with a conventional car, potentially more than half the vehicle’s usable lifetime. For drivers with low annual mileage in regions with dirty electricity grids, that breakeven point could take six to nine years to reach, if ever.

Battery manufacturing location proved enormously consequential. Production in China, powered by coal, generates 60-85% higher emissions than manufacturing in Europe or the United States. Yet Canadian subsidies flowed to companies regardless of where batteries were made or where vehicles would be charged. The federal government committed over $50 billion without requiring the environmental due diligence that should precede such massive public investment.

The Canadian government never acknowledged Volvo’s findings. Not once. A search of federal policy documents, ministerial statements, and environmental assessments from 2019 forward reveals no mention of the lifecycle complexities Volvo documented. Ottawa’s silence on inconvenient research speaks loudly about how ideology trumped evidence in shaping EV policy.

You want to build a pipeline in Canada. There will be 8 to 10 years of red tape and environmental impact assessments. But if you say you want to make EVs, Laurentian provincial premiers and the feds will bend over backwards. They handed over billions while the economy and social conditions in their cities decayed.

The environmental promise was conditional: clean electricity grids, high annual mileage, manufacturing in regions with low-carbon energy, and vehicles driven long enough to offset the massive carbon debt from battery production. Remove those conditions, and the environmental case collapses. The subsidies, however, remained unconditional.

The Subsidies Flow, The Companies Fail

Corporate casualties now litter the landscape. Northvolt received $240 million in federal subsidies to build a Quebec battery plant before filing for bankruptcy protection in November. Lion Electric, Quebec’s homegrown EV manufacturer, burned through $100 million in government support before announcing massive layoffs and production cuts. Arrival, which secured subsidies for its electric van facility, collapsed entirely, leaving taxpayers with nothing but broken promises.

Stellantis and LG Energy Solution extracted $15 billion, the most extensive corporate handout in Canadian history, for their Windsor battery plant. Volkswagen secured $13 billion for St. Thomas. Provincial governments layered on additional incentives. The public investment dwarfed any plausible return, yet the money kept flowing based on environmental claims the government either never bothered to verify or suppressed from its own documents and reports.

Despite this flood of subsidies and regulatory coercion, Canadian consumers rejected the offering. Even with massive incentives, EVs accounted for only 15% of new vehicle sales in 2024, far short of the mandated 20% target for 2026, let alone the 60% demanded by 2030. When federal subsidies ended in early 2025, sales collapsed to 9%, revealing the limited consumer demand. Dealer lots overflow with unsold inventory. Manufacturers scaled back production plans. The market spoke; Ottawa is only half listening.

The GM plant in Oshawa serves as a cautionary tale. Thousands of jobs lost. Promises of green manufacturing jobs evaporated. Workers who believed government assurances that EV mandates would secure their livelihoods found themselves unemployed as companies redirected production or collapsed entirely. The pattern repeats across the sector: subsidies extracted, production scaled back, workers laid off, taxpayers absorbing losses while executives collect bonuses and move on, and politicians pretend that it never happened. CBC isn’t asking Justin Trudeau, Katherine McKenna or Steven Guilbeault any questions about it. They are not asking Mark Carney.

The Central Planning Failure

The EV disaster illustrates why economies run by political offices never succeed. Friedrich Hayek observed that “The curious task of economics is to demonstrate to men how little they really know about what they imagine they can design.” Politicians and bureaucrats in Ottawa do not possibly possess the dispersed knowledge embedded in millions of individual economic decisions. But they think that they do.

Markets aggregate information that no central planner can access. Consumer preferences for vehicle range, charging convenience, and total cost of ownership. Regional variations in electricity generation and the pace of grid decarbonization. Battery technology improvements and supply chain vulnerabilities. Resource constraints and mining capacity. These factors interact in ways too complex for any cabinet planning committee to comprehend, yet Ottawa presumed to mandate outcomes a generation in advance.

Federal ministers with no experience in automotive manufacturing or battery chemistry presumed to direct the transformation of a trillion-dollar industry. Career bureaucrats drafted regulations determining which vehicles Canadians could purchase years hence, as if they possessed prophetic knowledge of technological development, grid decarbonization rates, consumer preferences, and global supply chains.

The EV mandate attempted to force a technological transition. It was an economic coup. Environmental claims proved conditional at best. Billions in subsidies flowed to failing companies. Taxpayers absorbed losses while corporations extracted rents and walked away. It worked well for the corporations, but the coup failed Canadians and Canadian workers. They are not building back better.

Green ideology provided perfect cover for this overreach. Invoke climate emergency, and fiscal responsibility vanishes. Question subsidies and you’re labelled a denier. Point out that environmental benefits depend on specific conditions, and you’re accused of spreading misinformation. The rhetorical shield, aided and abetted by a complicit media unable to see past its own financial interests, allowed government to bypass scrutiny that should attend any massive industrial policy intervention.

The Trust Deficit

As Canadians learn that EV environmental benefits depend heavily on electricity sources and driving patterns, as they watch subsidized companies collapse, as they discover how thoroughly the promise was oversold and how completely Ottawa ignored contrary evidence, trust in government erodes. This badly needed skepticism will spread beyond EVs and undermine legitimate government functions.

It would be good if future government claims about environmental policy face rising skepticism. Corporations wrapping themselves in green rhetoric may be viewed as con artists. Environmental activists who championed these policies may see their credibility destroyed. When citizens conclude their government systematically misled them about costs, benefits, and basic facts while suppressing inconvenient research, liberal democracy itself suffers. But that may not happen at all in Laurentian LaLa-land or in the Pacific Lotusland.

Over fifty billion dollars are distributed among local and foreign industrialists, while tens of thousands live in tents in Laurentian cities.

The EV debacle demonstrates that overselling policy benefits, suppressing complexity, and using ideology to short-circuit debate produce a backlash far worse than honest acknowledgment of nuance would have. The damage compounds when governments commit billions based on conditional environmental claims they never verified, then remain silent when industry-leading manufacturers publish data revealing those conditions.

The Path Forward

Canada needs a full repeal of the EV mandate and a complete retreat from Ottawa directing market decisions. The EV law must be struck, not merely paused. The 2030 and 2035 targets must be abandoned entirely. No new subsidies for EV production (or any other production). No bailouts for failed battery plants. No additional funds for charging infrastructure. And absolutely no subsidies for conventional or hybrid vehicle production justified by the same environmental complexity that should have prevented EV mandates in the first place.

Let markets determine which technologies Canadians choose. If EVs deliver genuine value for specific consumers in specific circumstances—those with clean electricity grids, high annual mileage, and long vehicle ownership timelines—those consumers will buy them without mandates or subsidies. If hybrids or improved conventional vehicles better serve other consumers’ needs, manufacturers will produce them without government direction.

The aggregated wisdom of millions of economic actors making decisions based on their actual circumstances will produce better outcomes than any planning committee in Ottawa. Some Canadians will find EVs deliver environmental and financial benefits. Others will not. Both conclusions can be correct simultaneously, a nuance Ottawa spent $50 billion refusing to acknowledge.

Markets work because no one has to know everything. Central planning fails because someone must. I wish I could say that Ottawa has learned this lesson the expensive way. Or whether Laurentians will remember it at the next election. Or whether the same politicians and bureaucrats who delivered this disaster will identify the next technology to mandate and subsidize, armed with new promises that reality will eventually expose as conditional at best.

But let’s keep our dreams in check. It seems more likely, given their ideological make-up and propensities for certainty, that low-information Laurentian and Pacific Coast voters will go right for the next green-washed fantasy that the feds and provincial governments will put in front of them, provided it is coiled into a catchy slogan.

Subscribe to Haultain Research.

For the full experience, and to help us bring you more quality research and commentary,

please upgrade your subscription.

-

Automotive2 days ago

Automotive2 days agoThe $50 Billion Question: EVs Never Delivered What Ottawa Promised

-

Alberta1 day ago

Alberta1 day agoAlberta introducing three “all-season resort areas” to provide more summer activities in Alberta’s mountain parks

-

COVID-191 day ago

COVID-191 day agoTrump DOJ seeks to quash Pfizer whistleblower’s lawsuit over COVID shots

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoStorm clouds of uncertainty as BC courts deal another blow to industry and investment

-

Agriculture1 day ago

Agriculture1 day agoGrowing Alberta’s fresh food future

-

International1 day ago

International1 day agoTrump admin wants to help Canadian woman rethink euthanasia, Glenn Beck says

-

Alberta1 day ago

Alberta1 day agoThe case for expanding Canada’s energy exports

-

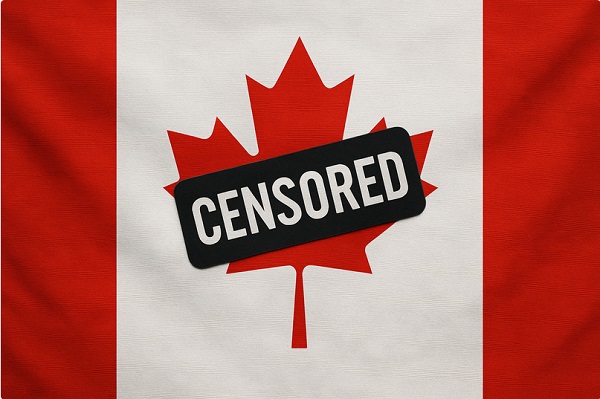

Censorship Industrial Complex24 hours ago

Censorship Industrial Complex24 hours agoOttawa’s New Hate Law Goes Too Far