Addictions

There’s No Such Thing as a “Safer Supply” of Drugs

By Adam Zivo

Sweden, the U.K., and Canada all experimented with providing opioids to addicts. The results were disastrous.

[This article was originally published in City Journal, a public policy magazine and website published by the Manhattan Institute for Policy Research. We encourage our readers to subscribe to them for high-quality analysis on urban issues]

Last August, Denver’s city council passed a proclamation endorsing radical “harm reduction” strategies to address the drug crisis. Among these was “safer supply,” the idea that the government should give drug users their drug of choice, for free. Safer supply is a popular idea among drug-reform activists. But other countries have already tested this experiment and seen disastrous results, including more addiction, crime, and overdose deaths. It would be foolish to follow their example.

The safer-supply movement maintains that drug-related overdoses, infections, and deaths are driven by the unpredictability of the black market, where drugs are inconsistently dosed and often adulterated with other toxic substances. With ultra-potent opioids like fentanyl, even minor dosing errors can prove fatal. Drug contaminants, which dealers use to provide a stronger high at a lower cost, can be just as deadly and potentially disfiguring.

Because of this, harm-reduction activists sometimes argue that governments should provide a free supply of unadulterated, “safe” drugs to get users to abandon the dangerous street supply. Or they say that such drugs should be sold in a controlled manner, like alcohol or cannabis—an endorsement of partial or total drug legalization.

But “safe” is a relative term: the drugs championed by these activists include pharmaceutical-grade fentanyl, hydromorphone (an opioid as potent as heroin), and prescription meth. Though less risky than their illicit alternatives, these drugs are still profoundly dangerous.

The theory behind safer supply is not entirely unreasonable, but in every country that has tried it, implementation has led to increased suffering and addiction. In Europe, only Sweden and the U.K. have tested safer supply, both in the 1960s. The Swedish model gave more than 100 addicts nearly unlimited access through their doctors to prescriptions for morphine and amphetamines, with no expectations of supervised consumption. Recipients mostly sold their free drugs on the black market, often through a network of “satellite patients” (addicts who purchased prescribed drugs). This led to an explosion of addiction and public disorder.

Most doctors quickly abandoned the experiment, and it was shut down after just two years and several high-profile overdose deaths, including that of a 17-year-old girl. Media coverage portrayed safer supply as a generational medical scandal and noted that the British, after experiencing similar problems, also abandoned their experiment.

While the U.S. has never formally adopted a safer-supply policy, it experienced something functionally similar during the OxyContin crisis of the 2000s. At the time, access to the powerful opioid was virtually unrestricted in many parts of North America. Addicts turned to pharmacies for an easy fix and often sold or traded their extra pills for a quick buck. Unscrupulous “pill mills” handed out prescriptions like candy, flooding communities with OxyContin and similar narcotics. The result was a devastating opioid epidemic—one that rages to this day, at a cumulative cost of hundreds of thousands of American lives. Canada was similarly affected.

The OxyContin crisis explains why many experienced addiction experts were aghast when Canada greatly expanded access to safer supply in 2020, following a four-year pilot project. They worried that the mistakes of the recent past were being made all over again, and that the recently vanquished pill mills had returned under the cloak of “harm reduction.”

Subscribe for free to get BTN’s latest news and analysis – or donate to our investigative journalism fund.

Most Canadian safer-supply prescribers dispense large quantities of hydromorphone with little to no supervised consumption. Patients can receive up to 40 eight-milligram pills per day—despite the fact that just two or three are enough to cause an overdose in someone without opioid tolerance. Some prescribers also provide supplementary fentanyl, oxycodone, or stimulants.

Unfortunately, many safer-supply patients sell or trade a significant portion of these drugs—primarily hydromorphone—in order to purchase more potent illicit substances, such as street fentanyl.

The problems with safer supply entered Canada’s consciousness in mid-2023, through an investigative report I wrote for the National Post. I interviewed 14 addiction physicians from across the country, who testified that safer-supply diversion is ubiquitous; that the street price of hydromorphone collapsed by up to 95 percent in communities where safer supply is available; that youth are consuming and becoming addicted to diverted safer-supply drugs; and that organized crime traffics these drugs.

Facing pushback, I interviewed former drug users, who estimated that roughly 80 percent of the safer-supply drugs flowing through their social circles was getting diverted. I documented dozens of examples of safer-supply trafficking online, representing tens of thousands of pills. I spoke with youth who had developed addictions from diverted safer supply and adults who had purchased thousands of such pills.

After months of public queries, the police department of London, Ontario—where safer supply was first piloted—revealed last summer that annual hydromorphone seizures rose over 3,000 percent between 2019 and 2023. The department later held a press conference warning that gangs clearly traffic safer supply. The police departments of two nearby midsize cities also saw their post-2019 hydromorphone seizures increase more than 1,000 percent.

The Canadian government quietly dropped its support for safer supply last year, cutting funding for many of its pilot programs. The province of British Columbia (the nexus of the harm-reduction movement) finally pulled back support last month, after a leaked presentation confirmed that safer-supply drugs are getting sold internationally and that the government is investigating 60 pharmacies for paying kickbacks to safer-supply patients. For now, all safer-supply drugs dispensed within the province must be consumed under supervision.

Harm-reduction activists have insisted that no hard evidence exists of widespread diversion of safer-supply drugs, but this is only because they refuse to study the issue. Most “studies” supporting safer supply are produced by ideologically driven activist-scholars, who tend to interview a small number of program enrollees. These activists also reject attempts to track diversion as “stigmatizing.”

The experiences of Sweden, the United Kingdom, and Canada offer a clear warning: safer supply is a reliably harmful policy. The outcomes speak for themselves—rising addiction, diversion, and little evidence of long-term benefit.

As the debate unfolds in the United States, policymakers would do well to learn from these failures. Americans should not be made to endure the consequences of a policy already discredited abroad simply because progressive leaders choose to ignore the record. The question now is whether we will repeat others’ mistakes—or chart a more responsible course.

Our content is always free –

but if you want to help us commission more high-quality journalism,

consider getting a voluntary paid subscription.

Addictions

Canada is divided on the drug crisis—so are its doctors

When it comes to addressing the national overdose crisis, the Canadian public seems ideologically split: some groups prioritize recovery and abstinence, while others lean heavily into “harm reduction” and destigmatization. In most cases, we would defer to the experts—but they are similarly divided here.

This factionalism was evident at the Canadian Society of Addiction Medicine’s (CSAM) annual scientific conference this year, which is the country’s largest gathering of addiction medicine practitioners (e.g., physicians, nurses, psychiatrists). Throughout the event, speakers alluded to the field’s disunity and the need to bridge political gaps through collaborative, not adversarial, dialogue.

This was a major shift from previous conferences, which largely ignored the long-brewing battles among addiction experts, and reflected a wider societal rethink of the harm reduction movement, which was politically hegemonic until very recently.

Recovery-oriented care versus harm reductionism

For decades, most Canadian addiction experts focused on shepherding patients towards recovery and encouraging drug abstinence. However, in the 2000s, this began to shift with the rise of harm reductionism, which took a more tolerant view of drug use.

On the surface, harm reductionists advocated for pragmatically minimizing the negative consequences of risky use—for example, through needle exchanges and supervised consumption sites. Additionally, though, many of them also claimed that drug consumption is not inherently wrong or shameful, and that associated harms are primarily caused not by drugs themselves but by the stigmatization and criminalization of their use. In their view, if all hard drugs were legalized and destigmatized, then they would eventually become as banal as alcohol and tobacco.

The harm reductionists gained significant traction in the 2010s thanks to the popularization of street fentanyl. The drug’s incredible potency caused an explosion of deaths and left users with formidable opioid tolerances that rendered traditional addiction medications, such as methadone, less effective. Amid this crisis, policymakers embraced harm reduction out of an immediate need to make drug use slightly less lethal. This typically meant supervising consumption, providing sterile drug paraphernalia, and offering “cleaner” substances for addicts to use.

Many abstinence-oriented addiction experts supported some aspects of harm reduction. They valued interventions that could demonstrably save lives without significant tradeoffs, and saw them as both transitional and as part of a larger public health toolkit. Distributing clean needles and Naloxone, an overdose-reversal medication, proved particularly popular. “People can’t recover if they’re dead,” went a popular mantra from the time.

Saving lives or enabling addiction?

However, many of these addiction experts were also uncomfortable with the broader political ideologies animating the movement and did not believe that drug use should be normalized. Many felt that some experimental harm reduction interventions in Canada were either conceptually flawed or that their implementation had deviated from what had originally been promised.

Some argued, not unreasonably, that the country’s supervised consumption sites are being mismanaged and failing to connect vulnerable addicts to recovery-oriented care. Most of their ire, however, was directed at “safer supply”—a novel strategy wherein addicts are given free drugs, predominantly hydromorphone (a heroin-strength opioid), without any real supervision.

While safer supply was meant to dissuade recipients from using riskier street drugs, addiction physicians widely reported that patients were selling their free hydromorphone to buy stronger illicit fentanyl, thereby flooding communities with diverted opioids and exacerbating the addiction crisis. They also noted that the “evidence base” behind safer supply was exceptionally poor and would not meet normal health-care standards.

Yet, critics of safer supply, and harm reduction radicalism more broadly, were often afraid to voice their opinions. The harm reductionists were institutionally and culturally dominant in the late 2010s and early 2020s, and opponents often faced activist harassment, aggressive gaslighting, and professional marginalization. A culture of self-censorship formed, giving both the public and influential policymakers a false impression of scientific consensus where none actually existed.

The resurgence in recovery-oriented strategies

Things changed in the mid-2020s. British Columbia’s failed drug decriminalization experiment eroded public trust in harm reductionism, and the scandalous failures of safer supply—and supervised consumption sites, too—were widely publicized in the national media.1

Whereas harm reductionism was once so powerful that opponents were dismissed as anti-scientific, there is now a resurgent interest in alternative, recovery-oriented strategies.

These cultural shifts have fuelled a more fractious, but intellectually honest, national debate about how to tackle the overdose crisis. This has ruptured the institutional dominance enjoyed by harm reductionists in the addiction medicine world and allowed their previously silenced opponents to speak up.

When I first attended CSAM’s annual scientific conference two years ago, recovery-oriented critics of radical harm reductionism were not given any platforms, with the exception of one minor presentation on safer supply diversion. Their beliefs seemed clandestine and iconoclastic, despite seemingly having wide buy-in from the addiction medicine community.

While vigorous criticism of harm reductionism was not a major feature of this year’s conference, there was open recognition that legitimate opposition to the movement existed. One major presentation, given by Dr. Didier Jutras-Aswad, explicitly cited safer supply and involuntary treatment as two foci of contention, and encouraged harm reductionists and recovery-oriented experts to grab coffee with one another so that they might foster some sense of mutual understanding.2

Is this change enough?

While CSAM should be commended for encouraging cross-ideological dialogue, its efforts, in this respect, were also superficial and vague. They chose to play it safe, and much was left unsaid and unexplored.

Two addiction medicine doctors I spoke with at the conference—both of whom were critics of safer supply and asked for anonymity—were nonplussed. “You can feel the tension in the air,” said one, who likened the conference to an awkward family dinner where everyone has tacitly agreed to ignore a recent feud. “Reconciliation requires truth,” said the other.

One could also argue that the organization has taken an inconsistent approach to encouraging respectful dialogue. When recovery-oriented experts were being bullied for their views a few years ago, they were largely left on their own. Now that their side is ascendant, and harm reductionists are politically vulnerable, mutual respect is in fashion again.

When I asked to interview the organization about navigating dissension, they sent a short, unspecific statement that emphasized “evidence-based practices” and the “benefits of exploring a variety of viewpoints, and the need to constantly challenge or re-evaluate our own positions based on the available science.”

But one cannot simply appeal to “evidence-based practices” when research is contentious and vulnerable to ideological meddling or misrepresentation.

Compared to other medical disciplines, addiction medicine is highly political. Grappling with larger, non-empirical questions about the role of drug use in society has always necessitated taking a philosophical stance on social norms, and this has been especially true since harm reductionists began emphasizing the structural forces that shape and fuel drug use.

Until Canada’s addiction medicine community facilitates a more robust and open conversation about the politicization of research, and the divided—and inescapably political—nature of their work, the national debate on the overdose crisis will be shambolic. This will have negative downstream impacts on policymaking and, ultimately, people’s lives.

Our content is always free – but if you want to help us commission more high-quality journalism,

consider getting a voluntary paid subscription.

Addictions

The War on Commonsense Nicotine Regulation

From the Brownstone Institute

Cigarettes kill nearly half a million Americans each year. Everyone knows it, including the Food and Drug Administration. Yet while the most lethal nicotine product remains on sale in every gas station, the FDA continues to block or delay far safer alternatives.

Nicotine pouches—small, smokeless packets tucked under the lip—deliver nicotine without burning tobacco. They eliminate the tar, carbon monoxide, and carcinogens that make cigarettes so deadly. The logic of harm reduction couldn’t be clearer: if smokers can get nicotine without smoke, millions of lives could be saved.

Sweden has already proven the point. Through widespread use of snus and nicotine pouches, the country has cut daily smoking to about 5 percent, the lowest rate in Europe. Lung-cancer deaths are less than half the continental average. This “Swedish Experience” shows that when adults are given safer options, they switch voluntarily—no prohibition required.

In the United States, however, the FDA’s tobacco division has turned this logic on its head. Since Congress gave it sweeping authority in 2009, the agency has demanded that every new product undergo a Premarket Tobacco Product Application, or PMTA, proving it is “appropriate for the protection of public health.” That sounds reasonable until you see how the process works.

Manufacturers must spend millions on speculative modeling about how their products might affect every segment of society—smokers, nonsmokers, youth, and future generations—before they can even reach the market. Unsurprisingly, almost all PMTAs have been denied or shelved. Reduced-risk products sit in limbo while Marlboros and Newports remain untouched.

Only this January did the agency relent slightly, authorizing 20 ZYN nicotine-pouch products made by Swedish Match, now owned by Philip Morris. The FDA admitted the obvious: “The data show that these specific products are appropriate for the protection of public health.” The toxic-chemical levels were far lower than in cigarettes, and adult smokers were more likely to switch than teens were to start.

The decision should have been a turning point. Instead, it exposed the double standard. Other pouch makers—especially smaller firms from Sweden and the US, such as NOAT—remain locked out of the legal market even when their products meet the same technical standards.

The FDA’s inaction has created a black market dominated by unregulated imports, many from China. According to my own research, roughly 85 percent of pouches now sold in convenience stores are technically illegal.

The agency claims that this heavy-handed approach protects kids. But youth pouch use in the US remains very low—about 1.5 percent of high-school students according to the latest National Youth Tobacco Survey—while nearly 30 million American adults still smoke. Denying safer products to millions of addicted adults because a tiny fraction of teens might experiment is the opposite of public-health logic.

There’s a better path. The FDA should base its decisions on science, not fear. If a product dramatically reduces exposure to harmful chemicals, meets strict packaging and marketing standards, and enforces Tobacco 21 age verification, it should be allowed on the market. Population-level effects can be monitored afterward through real-world data on switching and youth use. That’s how drug and vaccine regulation already works.

Sweden’s evidence shows the results of a pragmatic approach: a near-smoke-free society achieved through consumer choice, not coercion. The FDA’s own approval of ZYN proves that such products can meet its legal standard for protecting public health. The next step is consistency—apply the same rules to everyone.

Combustion, not nicotine, is the killer. Until the FDA acts on that simple truth, it will keep protecting the cigarette industry it was supposed to regulate.

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoCarney shrugs off debt problem with more borrowing

-

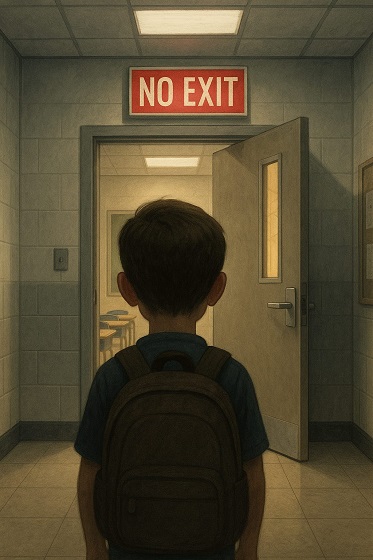

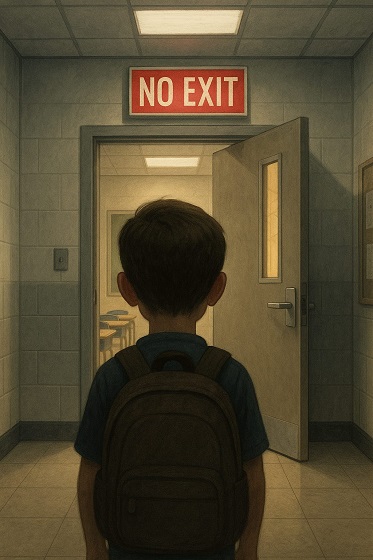

Alberta2 days ago

Alberta2 days agoWhen Teachers Say Your Child Has Nowhere Else to Go

-

Bruce Dowbiggin1 day ago

Bruce Dowbiggin1 day agoMaintenance Mania: Since When Did Pro Athletes Get So Fragile?

-

Automotive2 days ago

Automotive2 days agoThe high price of green virtue

-

Addictions1 day ago

Addictions1 day agoCanada is divided on the drug crisis—so are its doctors

-

MAiD2 days ago

MAiD2 days agoQuebec has the highest euthanasia rate in the world at 7.4% of total deaths

-

Daily Caller2 days ago

Daily Caller2 days agoProtesters Storm Elite Climate Summit In Chaotic Scene

-

National1 day ago

National1 day agoConservative bill would increase penalties for attacks on places of worship in Canada