Economy

The Net-Zero Dream Is Unravelling And The Consequences Are Global

From the Frontier Centre for Public Policy

The grand net-zero vision is fading as financial giants withdraw from global climate alliances

In recent years, governments and Financial institutions worldwide have committed to the goal of “net zero”—cutting greenhouse gas emissions to as close to zero as possible by 2050. One of the most prominent initiatives, the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ), sought to mobilize trillions of dollars by shifting investment away from fossil fuels and toward green energy projects.

The idea was simple in principle: make climate action a core part of financial decision-making worldwide.

The vision of a net-zero future, once championed as an inevitable path to global prosperity and environmental sustainability, is faltering. What began as an ambitious effort to embed climate goals into the flow of international capital is now encountering hard economic and political realities.

By redefining financial risk to include climate considerations, GFANZ aimed to steer financial institutions toward supporting a large-scale energy transition.

Banks and investors were encouraged to treat climate-related risks—such as the future decline of fossil fuels—as central to their financial strategies.

But the practical challenges of this approach have become increasingly clear.

Many of the green energy projects promoted under the net-zero banner have proven financially precarious without substantial government subsidies. Wind and solar technologies often rely on public funding and incentives to stay competitive. Energy storage and infrastructure upgrades, critical to supporting renewable energy, have also required massive financial support from taxpayers.

At the same time, institutions that initially embraced net-zero commitments are now facing soaring compliance costs, legal uncertainties and growing political resistance, particularly in major economies.

Major banks such as JPMorgan Chase, Citigroup and Goldman Sachs have withdrawn from GFANZ, citing concerns over operational risks and conflicting fuduciary duties. Their departure marks a signifcant blow to the alliance and signals a broader reassessment of climate finance strategies.

For many institutions, the initial hope that governments and markets would align smoothly around net-zero targets has given way to concerns over financial instability and competitive disadvantage. But that optimism has faded.

What once appeared to be a globally co-ordinated movement is fracturing. The early momentum behind net-zero policies was fuelled by optimism that government incentives and public support would ease the transition. But as energy prices climb and affordability concerns grow, public opinion has become noticeably more cautious.

Consumers facing higher heating bills and fuel costs are beginning to question the personal price of aggressive climate action.

Voters are increasingly asking whether these policies are delivering tangible benefits to their daily lives. They see rising costs in transportation, food production and home energy use and are wondering whether the promised green transition is worth the economic strain.

This moment of reckoning offers a crucial lesson: while environmental goals remain important, they must be pursued in balance with economic realities and the need for reliable energy supplies. A durable transition requires market-based solutions, technological innovation and policies that respect the complex needs of modern economies.

Climate progress will not succeed if it comes at the expense of basic affordability and economic stability.

Rather than abandoning climate objectives altogether, many countries and industries are recalibrating, moving away from rigid frameworks in favour of more pragmatic, adaptable strategies. Flexibility is becoming essential as governments seek to maintain public support while still advancing long term environmental goals.

The unwinding of GFANZ underscores the risks of over-centralized approaches to climate policy. Ambitious global visions must be grounded in reality, or they risk becoming liabilities rather than solutions. Co-ordinated international action remains important, but it must leave room for local realities and diverse economic circumstances.

As the world adjusts course, Canada and other energy-producing nations face a clear choice: continue down an economically restrictive path or embrace a balanced strategy that safeguards both prosperity and environmental stewardship. For countries like Canada, where natural resources remain a cornerstone of the economy, the stakes could not be higher.

The collapse of the net-zero consensus is not an end to climate action, but it is a wake-up call. The future will belong to those who learn from this moment and pursue practical, sustainable paths forward. A balanced approach that integrates environmental responsibility with economic pragmatism offers the best hope for lasting progress.

Marco Navarro-Genie is the vice president of research at the Frontier Centre for Public Policy. With Barry Cooper, he is coauthor of Canada’s COVID: The Story of a Pandemic Moral Panic (2023).

Business

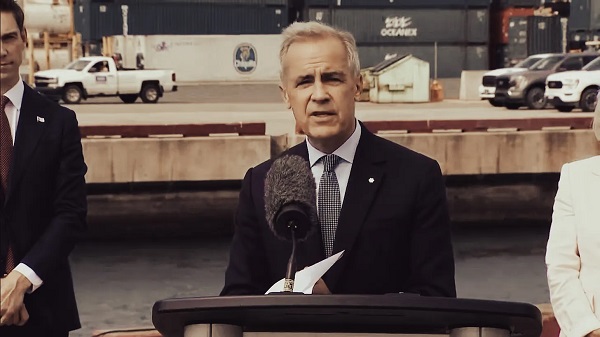

Carney’s ‘major projects’ list no cause for celebration

From the Fraser Institute

By Alex Whalen

Early in his term, Prime Minister Mark Carney placed great emphasis on the need to think big and move quickly, to make Canada the “world’s leading energy superpower.” Recently, the government announced the first group of projects to be championed by its new Major Projects Office (MPO), which was also recently created to circumvent existing rules and regulations to speed up approvals. Unfortunately, the list of projects is decidedly underwhelming, which highlights the need for a true course correction when it comes to fixing Canada’s investment crisis.

According to the government, the purpose of the Major Projects Office is to fast-track “nation building” projects, with a focus on regulatory approvals and financing. Yet, of the first five projects referred to the MPO, regulatory approvals have largely already been secured and the projects were likely to proceed without any intervention or assistance from Ottawa.

For example, many of the regulatory approvals required for the Darlington Small Nuclear Reactor are already in place, and construction has already begun. The McIlvenna Bay copper mine in Saskatchewan is already half-built.

Other projects, such as LNG Phase 2 and the Red Chris Copper Mine, both in British Columbia, are expansions of existing facilities and are backed by industry-leading firms such as Shell and Rio Tinto, respectively. In general, these projects do not need government assistance or financing since they’re already largely approved.

A further six projects being referred to the MPO are at an earlier stage of development, and for the most part do not yet require regulatory approvals. Carney has referred this list—which includes projects ranging from carbon capture to high speed rail to offshore wind—to the MPO to be matched with government “business development teams” to “advance these concepts.”

These initiatives parallel the approach by the Trudeau government to rely on government-directed projects to foster economic growth, which failed miserably. The Trudeau government’s economic policies featured a much larger role for government in the economy, including a general increase in the size and scope of the federal government, as measured by increased spending and regulation. The result? Under Trudeau, annual growth of per-person GDP (an indicator of living standards) was just 0.3 per cent, the worst track record of any recent prime minister. Net business investment (foreign direct investment in Canada minus Canadian direct investment abroad) declined by $388 billion between 2015 and 2023 (the latest year of available data).

To set Canada on a course to reverse the investment crisis, Carney must abandon the notion of government-directed economic growth. Approving projects already largely approved, while sending other less-certain projects to government business development bureaucrats, will not fix Canada’s problem. Simply put, the government should craft policy to create the right conditions for investment and entrepreneurship for all firms in all sectors of the economy, not simply its chosen winners.

To attract the kinds of major projects that will meaningfully improve Canada’s investment crisis, the Carney government should eliminate a host of regulations and reform those that survive. As other analysts have noted, the list of regulatory hurdles in Canada is long. Canada’s total regulatory load has increased substantially over time and across a wide range of industries including energy, autos, child care, supermarkets and more.

Nowhere is this more evident than the energy industry, which is one of the largest drivers of investment in Canada. Federal Bills C-69 and C-48 (which govern the project approval process and ban oil tankers on the west cost, respectively), alongside the federal greenhouse gas emissions cap, net-zero policies, and a host of other regulation such as new fuel standard have significantly constrained this industry, which is vital to Canada’s economic success.

Canada’s regulatory explosion has effectively decimated the country’s investment climate. While Bill C-5 allows cabinet to circumvent these regulations, it places the cabinet, and more specifically the prime minister, in the position of picking winners and losers. Broad-based tax and regulatory reduction and reform would be a much more effective approach.

Canada continues to struggle amid an investment crisis that’s holding back economic growth and living standards. Our country needs bold changes to the policy environment conducive to attracting more investment. The government’s response to date, through Bill C-5 and the MPO, involves making the government more, not less, involved in the economy. The government should reverse course.

Business

Global elites insisting on digital currency to phase out cash

From LifeSiteNews

By David James

The aim is to have the digital euro fully in place by 2030 in order to move Europe fully into the United Nations’ post-capitalist system described in Agenda 2030.

It always pays to scrutinize closely the comments of financial elites because they are rarely honest about their intentions. An instance is the comments of Christine Lagarde, president of the European Central Bank (ECB) who said there will be a vote next month in the European Union parliament on the next step toward creating a digital euro, which would be a central bank digital currency (CBDC).

A central bank digital currency is money issued by the central bank in digital form as opposed to digital credit issued by banks, which is the dominant form of money in Western societies. She claims that it will mean more freedom for Europeans and that there is nothing to fear.

Lagarde anticipates launching the digital euro in about 18 months. The aim is to have it fully in place by 2030 in order to move Europe fully into the United Nations’ post-capitalist system that is described in Agenda 2030.

Lagarde’s blandishments about what the digital euro represents do not survive close examination. She acknowledged that the main concern of the population is the privacy implications, claiming the ECB is looking at a technology that will offer protections. The private banks, she said, will apply the “rules of scrutiny” that already have access to the transactions. “We are not interested in the data. The private banks are interested in the data.”

Lagarde also said that the “people have dictated” the transition to a digital euro. This looks dubious. Neither the EU Commission nor the ECB is democratically elected. And if the main concern people have with a CBDC is privacy, then why would people prefer it over cash, which is immune to scrutiny? It is not as if a digital euro would satisfy an unmet need. Digital money – credit and online transactions – is already freely available in the banking system.

The ECB is also speaking out of both sides of its mouth, saying on one hand that the digital euro will only complement cash and on the other that cash will be eliminated.

Lagarde made it clear that the aim is to phase out cash completely. Agenda 2030, she claims, “can only be enforced in a cashless economy.” Why? What is it about cash that makes environmental policies impossible to implement? The answer is surely that a digital euro is needed to control people’s behavior, forcing them to comply with environmental rules.

Previous comments by central bankers suggest there is good reason for Europeans to be extremely suspicious. In 2021, the general manager of the Bank for International Settlements, Agustín Carstens, said: “We don’t know who’s using a $100 bill today and we don’t know who’s using a 1,000-peso bill today. The key difference with the CBDC is the central bank will have absolute control on the rules and regulations that will determine the use of that expression of central bank liability, and also we will have the technology to enforce that.”

The pretext for the financial power play is climate change and the push toward net zero. A European CBDC is not, as implied by Lagarde, the creation of a new digital monetary mechanism. As economist Richard Werner points out, that already exists – credit and debit cards, for example. The significance of a digital euro is that it threatens the banking system.

A CBDC, like cash, has no interest rate on it. So why would people continue to use credit produced by private entities such as banks or credit card companies – currently over 95 percent of the money supply – on which they have to pay interest? As the Reserve Bank of New Zealand noted, CBDCs have the potential to destroy private banks.

That problem does not seem to concern the ECB, however. Indeed, fundamentally altering the banking system may be what they are aiming for. Lagarde said “climate compliance” will become a core element of bank supervision, not a separate initiative, “because climate change presents significant, material financial risks to banks and the entire financial system.”

The ECB’s supervision will mandate that banks integrate the management of climate-related and environmental risks into their existing risk management processes, particularly through new prudential transition planning requirements under what is called CRD VI. European banking, it seems, will no longer be defined by profitability and fiscal soundness but also by the politics of climate change.

The slipperiness of the ECB‘s arguments point to a much darker ambition. Werner says when CBDCs are connected to digital IDs “we are talking about the most totalitarian control system in human history … it gives you as a controller complete visibility on what everyone is doing, every transaction.

“The monitoring is only one aspect. These CBDCs are programmable and you can use big data algorithms, which they sell to us as artificial intelligence, in order to have rules about who can buy what and for what purpose, at what time and at what place – and therefore control all your movement. In the history of dictatorships, there never has been such a powerful control tool.”

There is a flaw, though, in the ECB’s push to change Europe’s financial architecture that may prove fatal to its ambitions. The EU and ECB do not have genuine central control. When the euro was established in 1998, the only way Germany was able to join was on the condition there was no consolidation of the government debt. So, although the ECB notionally sets interest rates for the zone, government debt is held at the national level and each country’s interest rate differs.

The ECB is thus a central bank in name only, unlike the U.S. Federal Reserve, or for that matter most country’s central banks, that oversee their national government debt. A European nation can choose to exit the EU, and each has to have its own monetary policy in spite of the ECB setting a uniform rate.

The push to create a digital euro is most likely an attempt to deal with these contradictions, but at best it will be a makeshift solution and it will take very little for it to fall apart. Disintegration of the European Union, and the common currency, is not out of the question.

Meanwhile, the U.S. is going in the opposite direction. In July, the U.S. House of Representatives passed the Anti-CBDC Surveillance State Act, which prevents the Federal Reserve from issuing a retail CBDC directly to individuals.

European debt is becoming increasingly parlous, especially in France where there have even been suggestions that there might need to be assistance from the International Monetary Fund. Italy’s debt, which is 138 percent of GDP, is also problematic. Lagarde is hoping for a rollout of the digital euro in 2027 and completion in 2030. But the Euro zone, and the ECB that oversees it, may not last that long.

-

National2 days ago

National2 days agoChrystia Freeland resigns from Mark Carney’s cabinet, asked to become Ukraine envoy

-

International2 days ago

International2 days agoFrance records more deaths than births for the first time in 80 years

-

Energy1 day ago

Energy1 day agoA Breathtaking About-Face From The IEA On Oil Investments

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoOttawa’s so-called ‘Clean Fuel Standards’ cause more harm than good

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoThe Truth Is Buried Under Sechelt’s Unproven Graves

-

Alberta2 days ago

Alberta2 days agoParents group blasts Alberta government for weakening sexually explicit school book ban

-

Health1 day ago

Health1 day agoCanadians diagnosed with cancer in ER struggle to receive treatment as Liberals keep pushing MAiD

-

Frontier Centre for Public Policy2 days ago

Frontier Centre for Public Policy2 days agoBloodvein Blockade Puts Public Land Rights At Risk