Business

The government surrenders to reality with rewritten Online News Act—and pleases no one: Peter Menzies

From the MacDonald Laurier Institute

By Peter Menzies

The shakedown of Meta and Google didn’t go as planned—but now they’re eyeing other lucrative targets.

There were some long faces in the news industry last week when Heritage Minister Pascale St-Onge rolled out the final terms of her surrender to reality.

Media executives who once campaigned for the Online News Act with sugar-plum visions of Big Tech cash dancing in their heads were left to deal with some pretty serious lumps of coal. After years of effort to procure what they once fancied would be hundreds of millions of dollars annually from web giants, all St-Onge could bring down the chimney was a bump up in Google’s spend to $100 million.

How much the mother of all search engines was already paying to publishers is unknown, but in-the-know estimates tend to range from $30-$50 million. Splitting the difference at $40 million would mean the industry—newspapers, broadcasters, and online platforms—wound up with $60 million in fresh cash, give or take.

That’s less than the Lotto Max jackpot Rhonda Malesku of Kamloops and Ruth Bowes of Edmonton shared last summer. A lot of money for Rhonda and Ruth for sure, but for an entire industry it’s a drop in a leaky bucket.

Then there’s the fact the Act resulted in Meta blocking all news links in Canada on Facebook and Instagram. Again, the exact cost is unknown but the social media company had been spending $18 million on journalism supports plus—and here is the killer—Meta estimated it had been sending $230 million a year worth of referrals to news websites.

Even if Meta is only half right, that still leaves the news industry many tens of millions of dollars worse off. If Meta’s estimate is accurate—and no one has really debunked it—the scenario is a lot uglier.

This is what happens when you make things up.

The Act was rooted in the make-believe premise that “web giants” were profiting from “stealing” news. Legislation was designed on that basis to force Big Tech to “negotiate” commercial deals and share those profits with all news organizations.

In the end, as Michael Geist has detailed, that charade of “compensation” was dropped as the government, desperately afraid Google would follow Meta’s lead, posted regulations that essentially rewrote the Act to suit the search engine and, as an aside, puzzle lawyers. All that the media were able to salvage from the hustle was a fund they wound up fighting over like street urchins in a soup kitchen.

Here, St-Onge actually did something sensible. Her original plan was to have the fund distributed solely on a per journo basis. In other words, if there are 10,000 journalists, $100 million would turn into $10,000 per journo, never mind whether they are paid $35,000 or $150,000. The problem with that is that one in three Canadian reporters works for CBC, which is not in mortal peril. The next highest is Bell Media, whose parent company made $10 billion last year. Meanwhile, the Toronto Star is hemorrhaging at a rate of $1 million a week, small centres are becoming news deserts, and Postmedia’s stable of zombie newspapers continues to, well, zombie on.

Broadcasters would have consumed 75 percent of the loot and the vast majority of the cash would wind up with companies for whom news is not a primary aspect of their operations.

St-Onge changed that to cap private broadcasters’ windfall at 30 percent, with CBC limited to 7 percent.

That means 63 percent of the money will go to operators in the greatest peril which, for a fund resulting from a need to address industrial poverty, is at least rational.

Still, there was grumbling.

“Well, this is disappointing—sure wasn’t expecting a cap on broadcasters’ access to compensation,” Tandy Yull, vice president of policy and regulatory affairs for the Canadian Association of Broadcasters, posted on LinkedIn.

“Hey, Universe! More needs to be done to support Canadians’ most important providers of news, local radio, and television stations, who are facing significant—even existential—declines in advertising revenue,” she added.

Yull went on to stake broadcasters’ claim to government assistance currently reserved for newspapers and online-only media: the Journalism Labour Tax Credit and the Local Journalism Initiative.

And of course “our democracy demands that we explore these and other options—soon.”

She may not have long to wait.

Broadcasters opened up a fresh lobbying for loot campaign just last month when the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) held a hearing to launch the implementation of the Online Streaming Act.

Supposedly about funding Canadian entertainment programming, the concept of a news fund was introduced early and repeated often.

Commissioners appeared happy to embrace well-worn lines about a news “crisis” that needs “urgent” attention to prevent—cue the tympany—the death of democracy. And they did so without needing to be persuaded there was any rational reason for creating a fund which, logically, makes no more sense than taxing cinemas to pay for newspapers. Nor were any concerns raised about impacts on entrepreneurship and online innovators.

“Local news is in crisis and requires immediate intervention,” Susan Wheeler of Rogers, which made $7.12 billion last year, told the panel.

“A fundamental outcome of the modernized contribution regime must include new mechanisms to provide long‑term financial support for high‑quality Canadian‑produced broadcast news from credible outlets,” she said, calling for 30 percent of money raised from foreign online streaming companies to be directed to a news fund “accessible by all private TV and radio stations producing news.”

The humiliating squabbling over the remnant scraps of the Online News Act clearly wasn’t the end of the Great Canadian Quest for other people’s money.

So maybe the shakedown of Meta and Google didn’t quite work out. But Spotify, Disney+, and Netflix? They have money. Let’s mug them instead.

It’s not like anything bad could happen. Right?

Peter Menzies is a Senior Fellow with the Macdonald-Laurier Institute, a former newspaper executive, and past vice chair of the CRTC.

Business

Red tape is killing Canadian housing affordability

This article supplied by Troy Media.

By Conrad Eder

By Conrad Eder

Bureaucracy and bad policy, not demand, are driving up housing prices

Imagine putting down a hefty deposit on an $800,000 pre-construction condo only to find out at closing that your unit is now worth $1 million.

That’s a $200,000 shortfall. Since banks lend based on appraised value, you’re left with two choices: cough up the extra cash or walk away and kiss your deposit goodbye.

Canada’s housing affordability crisis isn’t just about rising prices—it’s about a broken system that can’t keep up with what people actually need.

This isn’t an isolated nightmare. In major cities across Canada, appraisals are landing 10 to 30 per cent below contract prices. And it’s exposing a deeper dysfunction in our housing market.

Toronto alone has more than 24,000 unsold new condos. Units that once attracted investors and young professionals now sit empty while developers keep building more of the same—small, overpriced boxes nobody’s clamouring for. Meanwhile, buyers are hunting for larger, livable spaces they either can’t afford or can’t find.

Yet despite the demand for larger, livable spaces, the system keeps producing what no one really wants.

How did we get here? It’s not just about supply and demand. It’s about municipal red tape and sluggish approval systems that choke off the market’s ability to respond to changing needs.

If we’re serious about affordability, we have to fix this bottleneck. That starts with slashing approval timelines so homes can actually be built where and how people want them.

These delays don’t just frustrate builders: they limit housing supply, inflate prices and leave Canadians competing for homes that don’t fit their lives or budgets.

Across the country, getting from concept to construction can take years. The planning grind—permits, consultations, rezoning, environmental assessments—drags on and racks up indirect costs of as much as $5,576 per unit per month.

In Toronto, approvals average 25 months. That delay alone can tack on more than $100,000 to the final price of a condo. In Hamilton, it’s 31 months.

And those delays don’t just raise costs—they throw off timing. By the time a project finally breaks ground, the market has often moved on, leaving developers stuck delivering yesterday’s housing to today’s buyers.

Even those who can afford larger units hesitate to commit. Who wants to wait years just to move in, especially when the price is climbing the entire time?

Unsurprisingly, larger units are often the last to sell—too costly for most, too delayed for the rest.

The result? A steady stream of undersized condos that few actually want, offered at prices most can barely justify.

Yes, regulation has a place. But among the 35 member countries of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Canada ranks 34th in approval speed, with an average of 249 days. That’s not oversight—that’s paralysis. Countries with similarly strong environmental and safety standards manage to approve projects in half the time. So what’s our excuse?

It doesn’t have to be this way. Some cities are proving that faster approvals don’t mean cutting corners—they just mean cutting red tape. Between 2022 and 2024, Halifax slashed its approval timelines from 20.8 months to 9.8. Edmonton went from 10.5 months to just 3.4, without compromising

safety or public input.

Other cities could follow suit by adopting tools like automated same-day permits, consolidating overlapping policies, creating fast-track review lanes for compliant developers and publishing timelines to inject predictability and accountability into the process.

Let’s be clear: this isn’t about giving developers a free ride. It’s about giving Canadians more choice, better options and a fighting chance at ownership.

Unlike interest rates or material costs, these delays are entirely within government control. If policymakers actually want a responsive housing market, they need to stop jamming the gears.

They aren’t stuck with these timelines. They’re choosing them. And those choices are making housing more expensive while preventing the market from delivering what Canadians need, when they need it.

Conrad Eder is a policy analyst at the Frontier Centre for Public Policy.

Explore more on Housing, Canadian economy, Cost of Living, Municipal politics

Troy Media empowers Canadian community news outlets by providing independent, insightful analysis and commentary. Our mission is to support local media in helping Canadians stay informed and engaged by delivering reliable content that strengthens community connections and deepens understanding across the country.

Business

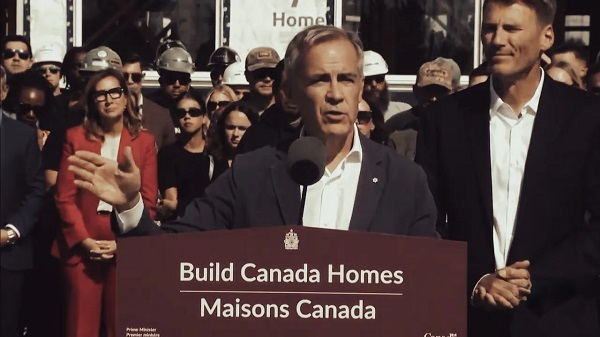

Carney’s ‘major projects’ list no cause for celebration

From the Fraser Institute

By Alex Whalen

Early in his term, Prime Minister Mark Carney placed great emphasis on the need to think big and move quickly, to make Canada the “world’s leading energy superpower.” Recently, the government announced the first group of projects to be championed by its new Major Projects Office (MPO), which was also recently created to circumvent existing rules and regulations to speed up approvals. Unfortunately, the list of projects is decidedly underwhelming, which highlights the need for a true course correction when it comes to fixing Canada’s investment crisis.

According to the government, the purpose of the Major Projects Office is to fast-track “nation building” projects, with a focus on regulatory approvals and financing. Yet, of the first five projects referred to the MPO, regulatory approvals have largely already been secured and the projects were likely to proceed without any intervention or assistance from Ottawa.

For example, many of the regulatory approvals required for the Darlington Small Nuclear Reactor are already in place, and construction has already begun. The McIlvenna Bay copper mine in Saskatchewan is already half-built.

Other projects, such as LNG Phase 2 and the Red Chris Copper Mine, both in British Columbia, are expansions of existing facilities and are backed by industry-leading firms such as Shell and Rio Tinto, respectively. In general, these projects do not need government assistance or financing since they’re already largely approved.

A further six projects being referred to the MPO are at an earlier stage of development, and for the most part do not yet require regulatory approvals. Carney has referred this list—which includes projects ranging from carbon capture to high speed rail to offshore wind—to the MPO to be matched with government “business development teams” to “advance these concepts.”

These initiatives parallel the approach by the Trudeau government to rely on government-directed projects to foster economic growth, which failed miserably. The Trudeau government’s economic policies featured a much larger role for government in the economy, including a general increase in the size and scope of the federal government, as measured by increased spending and regulation. The result? Under Trudeau, annual growth of per-person GDP (an indicator of living standards) was just 0.3 per cent, the worst track record of any recent prime minister. Net business investment (foreign direct investment in Canada minus Canadian direct investment abroad) declined by $388 billion between 2015 and 2023 (the latest year of available data).

To set Canada on a course to reverse the investment crisis, Carney must abandon the notion of government-directed economic growth. Approving projects already largely approved, while sending other less-certain projects to government business development bureaucrats, will not fix Canada’s problem. Simply put, the government should craft policy to create the right conditions for investment and entrepreneurship for all firms in all sectors of the economy, not simply its chosen winners.

To attract the kinds of major projects that will meaningfully improve Canada’s investment crisis, the Carney government should eliminate a host of regulations and reform those that survive. As other analysts have noted, the list of regulatory hurdles in Canada is long. Canada’s total regulatory load has increased substantially over time and across a wide range of industries including energy, autos, child care, supermarkets and more.

Nowhere is this more evident than the energy industry, which is one of the largest drivers of investment in Canada. Federal Bills C-69 and C-48 (which govern the project approval process and ban oil tankers on the west cost, respectively), alongside the federal greenhouse gas emissions cap, net-zero policies, and a host of other regulation such as new fuel standard have significantly constrained this industry, which is vital to Canada’s economic success.

Canada’s regulatory explosion has effectively decimated the country’s investment climate. While Bill C-5 allows cabinet to circumvent these regulations, it places the cabinet, and more specifically the prime minister, in the position of picking winners and losers. Broad-based tax and regulatory reduction and reform would be a much more effective approach.

Canada continues to struggle amid an investment crisis that’s holding back economic growth and living standards. Our country needs bold changes to the policy environment conducive to attracting more investment. The government’s response to date, through Bill C-5 and the MPO, involves making the government more, not less, involved in the economy. The government should reverse course.

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoCarney Admits Deficit Will Top $61.9 Billion, Unveils New Housing Bureaucracy

-

Alberta1 day ago

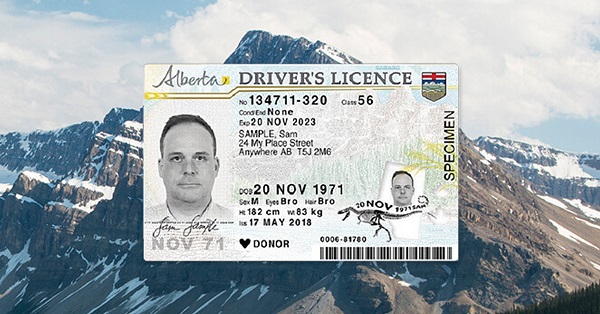

Alberta1 day agoAlberta first to add citizenship to licenses

-

Alberta1 day ago

Alberta1 day agoBreak the Fences, Keep the Frontier

-

Business7 hours ago

Business7 hours agoCarney’s ‘major projects’ list no cause for celebration

-

Business6 hours ago

Business6 hours agoRed tape is killing Canadian housing affordability

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoCarney’s Ethics Test: Opposition MP’s To Challenge Prime Minister’s Financial Ties to China

-

Business8 hours ago

Business8 hours agoGlobal elites insisting on digital currency to phase out cash

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoAttrition doesn’t go far enough, taxpayers need real cuts