Opinion

SOMEBODY SHOULD DO SOMETHING

?

I listened to another conversation about the continued decline of the neighbourhoods north of the river. It was the sense of acceptance that these neighbourhoods were so inferior and undesirable that worried me.

These are educated people, accepting something that should be abhorrent.

Remember 1985. Parkland Mall was a vibrant shopping destination, for Central Alberta. 40 percent of the residents lived north of the river. The last school north of the river was built. The Dawe Centre was open and then the clock stopped.

Now, in 2017, Parkland Mall is but a shadow of it’s former south and only 30 percent of the residents live north of the river, the population actually declined by 777 residents last year.

The school that was to be built in Johnstone Park, was when it came to be built was built south of the river, and the school site was turned into a park. The superintendent e-mailed me and explained that the growth was in the south. I asked if their policies was actually assisting in the mass relocating of the north side residents and I was brushed off with the standard; “Something to think about” response. I noted that in the planning of 5 square miles of land north of 11a there are only 2 sites for schools but in the plans around the 67 Street and 30 Avenue traffic circle there are 9 sites with 3 high schools. Again; “Something to think about”.

With 30,000 residents with plans for 55,000 residents north of the river is there no plans for a high school? Blackfalds and Penhold will have a high school. The residents south of the river will have 6 high schools with 5 high schools along 30 Avenue between 29 Street and 69 Street. Somebody should do something so people will not move out from the north side because the school that was promised will not be built and there are no high schools planned. Wait 777 residents did move out last year, is there a connection? Do families want to move into neighbourhoods near their children’s schools?

Perhaps families would rather live near recreation centres? On the north side of the river we have the Dawe Centre, built in the 70s, and there are no plans to build a new recreation centre, including a swimming pool.

On the south side we only have; the Downtown Recreation Centre, Michener Aquatic Centre, Downtown Arena, Centrium complex, Collicutt Recreation Centre, Pidherney Curling Centre, Kinex Arena, Kinsmen Community Arenas, Red Deer Curling Centre, and the under-construction Gary W. Harris Centre. The city is also talking about replacing the downtown recreation centre with an expanded 50m pool.

A little lop-sided would you not say. Somebody should do something.

Back to this conversation. If it is accepted that the neighbourhoods north of the river, are lower income, less educated and have higher crime and poorer air, are we creating these scenarios with our policies. Why do we build high schools easily accessible to the higher income families and make the lower income families drive across the city? Same with the recreational complexes. Are we pushing the young people out to the streets because they do not have the time to travel across the city to participate in extra curricular activities let alone the funds for travel? Somebody should do something.

Perhaps the citizens north of the river should create a block of candidates for the municipal election this October. A block of trustee candidates for each school board and a block of candidates for city council. Perhaps individuals could run on that platform if not demand answers as to why we continue with this discrimination of the north side of the river. Again; Somebody should do something.

Before it gets any worse.

Energy

Unceded is uncertain

Tsawwassen Speaker Squiqel Tony Jacobs arrives for a legislative sitting. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Darryl Dyck

From Resource Works

Cowichan case underscores case for fast-tracking treaties

If there are any doubts over the question of which route is best for settling aboriginal title and reconciliation – the courts or treaty negotiations – a new economic snapshot on the Tsawwassen First Nation should put the question to rest.

Thanks to a modern day treaty, implemented in 2009, the Tsawwassen have leveraged land, cash and self-governance to parlay millions into hundreds of millions a year, according to a new report by Deloitte on behalf of the BC Treaty Commission.

With just 532 citizens, the Tsawwassen First Nation now provides $485 million in annual employment and 11,000 permanent retail and warehouse jobs, the report states.

Deloitte estimates modern treaties will provide $1 billion to $2 billion in economic benefits over the next decade.

“What happens, when you transfer millions to First Nations, it turns into billions, and it turns into billions for everyone,” Sashia Leung, director of international relations and communication for the BC Treaty Commission, said at the Indigenous Partnership Success Showcase on November 13.

“Tsawwassen alone, after 16 years of implementing their modern treaty, are one of the biggest employers in the region.”

BC Treaty Commission’s Sashia Leung speaks at the Indigenous Partnerships Success Showcase 2025.

Nisga’a success highlights economic potential

The Nisga’a is another good case study. The Nisga’a were the first indigenous group in B.C. to sign a modern treaty.

Having land and self-governance powers gave the Nisga’a the base for economic development, which now includes a $22 billion LNG and natural gas pipeline project – Ksi Lisims LNG and the Prince Rupert Gas Transmission line.

“This is what reconciliation looks like: a modern Treaty Nation once on the sidelines of our economy, now leading a project that will help write the next chapter of a stronger, more resilient Canada,” Nisga’a Nation president Eva Clayton noted last year, when the project received regulatory approval.

While the modern treaty making process has moved at what seems a glacial pace since it was established in the mid-1990s, there are some signs of gathering momentum.

This year alone, three First Nations signed final treaty settlement agreements: Kitselas, Kitsumkalum and K’omoks.

“That’s the first time that we’ve ever seen, in the treaty negotiation process, that three treaties have been initialed in one year and then ratified by their communities,” Treaty Commissioner Celeste Haldane told me.

Courts versus negotiation

When it comes to settling the question of who owns the land in B.C. — the Crown or First Nations — there is no one-size-fits-all pathway.

Some First Nations have chosen the courts. To date, only one has succeeded in gaining legal recognition of aboriginal title through the courts — the Tsilhqot’in.

The recent Cowichan decision, in which a lower court recognized aboriginal title to a parcel of land in Richmond, is by no means a final one.

That decision opened a can of worms that now has private land owners worried that their properties could fall under aboriginal title. The court ruling is being appealed and will almost certainly end up having to go to the Supreme Court.

This issue could, and should, be resolved through treaty negotiations, not the courts.

The Cowichan, after all, are in the Hul’qumi’num treaty group, which is at stage 5 of a six-stage process in the BC Treaty process. So why are they still resorting to the courts to settle title issues?

The Cowichan title case is the very sort of legal dispute that the B.C. and federal governments were trying to avoid when it set up the BC Treaty process in the mid-1990s.

Accelerating the process

Unfortunately, modern treaty making has been agonizingly slow.

To date, there are only seven modern implemented treaties to show for three decades of works — eight if you count the Nisga’a treaty, which predated the BC Treaty process.

Modern treaty nations include the Nisga’a, Tsawwassen, Tla’amin and five tribal groups in the Maa-nulth confederation on Vancouver Island.

It takes an average of 10 years to negotiate a final treaty settlement. Getting a court ruling on aboriginal title can take just as long and really only settles one question: Who owns the land?

The B.C. government has been trying to address rights and title through other avenues, including incremental agreements and a tripartite reconciliation process within the BC Treaty process.

It was this latter tripartite process that led to the Haida agreement, which recognized Haida title over Haida Gwaii earlier this year.

These shortcuts chip away at issues of aboriginal rights and title, self-governance, resource ownership and taxation and revenue generation.

Modern treaties are more comprehensive, settling everything from who owns the land and who gets the tax revenue from it, to how much salmon a nation is entitled to annually.

Once modern treaties are in place, it gives First Nations a base from which to build their own economies.

The Tsawwassen First Nation is one of the more notable case studies for the economic and social benefits that accrue, not just to the nation, but to the local economy in general.

The Tsawwassen have used the cash, land and taxation powers granted to them under treaty to create thousands of new jobs. This has been done through the development of industrial, commercial and residential lands.

This includes the development of Tsawwassen Mills and Tsawwassen Commons, an Amazon warehouse, a container inspection centre, and a new sewer treatment plant in support of a major residential development.

“They have provided over 5,000 lease homes for Delta, for Vancouver,” Leung noted. “They have a vision to continue to build that out to 10,000 to 12,000.”

Removing barriers to agreement

For First Nations, some of the reticence in negotiating a treaty in the past was the cost and the loss of tax exemptions. But those sticking points have been removed in recent years.

First Nations in treaty negotiations were originally required to borrow money from the federal government to participate, and then that loan amount was deducted from whatever final cash settlement was agreed to.

That requirement was eliminated in 2019, and there has been loan forgiveness to those nations that concluded treaties.

Another sticking point was the loss of tax exemptions. Under Section 87 of Indian Act, sales and property taxes do not apply on reserve lands.

But under modern treaties, the Indian Act ceases to apply, and reserve lands are transferred to title lands. This meant giving up tax exemptions to get treaty settlements.

That too has been amended, and carve-outs are now allowed in which the tax exemptions can continue on those reserve lands that get transferred to title lands.

“Now, it’s up to the First Nation to determine when and if they want to phase out Section 87 protections,” Haldane said.

Haldane said she believes these recent changes may account for the recent progress it has seen at the negotiation table.

“That’s why you’re seeing K’omoks, Kitselas, Kitsumkalum – three treaties being ratified in one year,” she said. “It’s unprecedented.”

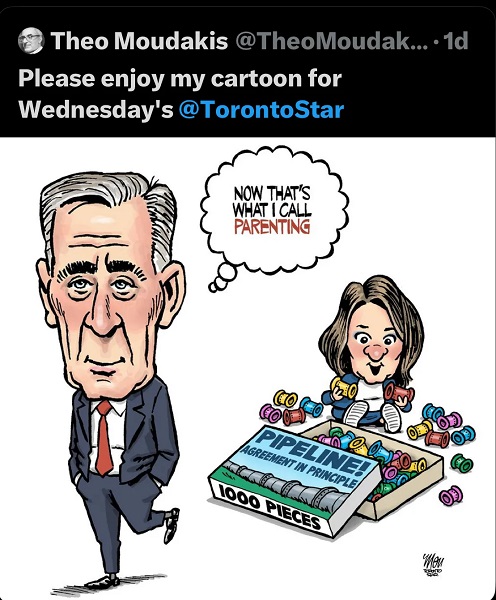

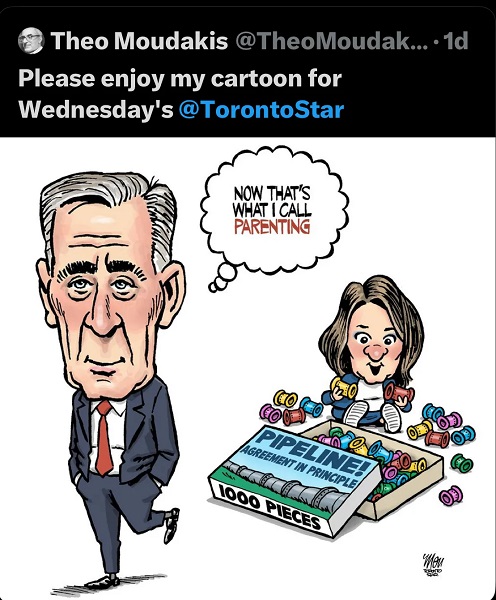

The Mark Carney government has been on a fast-tracking kick lately. But we want to avoid the kind of uncertainty that the Cowichan case raises, and if the Carney government is looking for more things to fast-track that would benefit First Nations and the Canadian economy, perhaps treaty making should be one of them.

Resource Works News

Automotive

Power Struggle: Governments start quietly backing away from EV mandates

From Resource Works

Barry Penner doesn’t posture – he brings evidence. And lately, the evidence has been catching up fast to what he’s been saying for months.

Penner, chair of the Energy Futures Institute and a former B.C. environment minister and attorney-general, walked me through polling that showed a decisive pattern: declining support for electric-vehicle mandates, rising opposition, and growing intensity among those pushing back.

That was before the political landscape started shifting beneath our feet.

In the weeks since our conversation, the B.C. government has begun retreating from its hardline EV stance, softening requirements and signalling more flexibility. At the same time, Ottawa has opened the door to revising its own rules, acknowledging what the market and motorists have been signalling for some time.

Penner didn’t need insider whispers to see this coming. He had the data.

Barry Penner, Chair of the Energy Futures Institute

B.C.’s mandate remains the most aggressive in North America: 26 per cent ZEV sales by 2026, 90 per cent by 2030, and 100 per cent by 2035. Yet recent sales paint a different picture. Only 13 per cent of new vehicles sold in June were electric. “Which means 87 per cent weren’t,” Penner notes. “People had the option. And 87 per cent chose a non-electric.”

Meanwhile, Quebec has already adjusted its mandate to give partial credit for hybrids. Polling shows 76 per cent of British Columbians want the same. The trouble? “There’s a long waiting list to get one,” Penner says.

Cost, charging access and range remain the top barriers for consumers. And with rebates shrinking or disappearing altogether, the gap between policy ambition and practical reality is now impossible for governments to ignore.

Penner’s advice is simple, and increasingly unavoidable: “Recognition of reality is in order.”

- Now watch Barry Penner’s full video interview with Stewart Muir on Power Struggle here:

-

National2 days ago

National2 days agoMedia bound to pay the price for selling their freedom to (selectively) offend

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoIs there a cure for Alzheimer’s Disease?

-

C2C Journal2 days ago

C2C Journal2 days agoLearning the Truth about “Children’s Graves” and Residential Schools is More Important than Ever

-

Bruce Dowbiggin2 days ago

Bruce Dowbiggin2 days agoSometimes An Ingrate Nation Pt. 2: The Great One Makes His Choice

-

Alberta2 days ago

Alberta2 days agoNew era of police accountability

-

Brownstone Institute2 days ago

Brownstone Institute2 days agoThe Unmasking of Vaccine Science

-

Alberta1 day ago

Alberta1 day agoEmissions Reduction Alberta offering financial boost for the next transformative drilling idea

-

Business18 hours ago

Business18 hours agoRecent price declines don’t solve Toronto’s housing affordability crisis