Health

Prostate Cancer: Over-Testing and Over-Treatment

From the Brownstone Institute

By

The excessive medical response to the Covid pandemic made one thing abundantly clear: Medical consumers really ought to do their own research into the health issues that impact them. Furthermore, it is no longer enough simply to seek out a “second opinion” or even a “third opinion” from doctors. They may well all be misinformed or biased. Furthermore, this problem appears to predate the Covid phenomenon.

A striking example of that can be found in the recent history of prostate cancer testing and treatment, which, for personal reasons, has become a subject of interest to me. In many ways, it strongly resembles the Covid calamity, where misuse of the PCR test resulted in harming the supposedly Covid-infected with destructive treatments.

Two excellent books on the subject illuminate the issues involved in prostate cancer. One is Invasion of the Prostate Snatchers by Dr. Mark Scholz and Ralph Blum. Dr. Scholtz is executive director of the Prostate Cancer Research Institute in California. The other is The Great Prostate Hoax by Richard Ablin and Ronald Piana. Richard Ablin is a pathologist who invented the PSA test but has become a vociferous critic of its widespread use as a diagnostic tool for prostate cancer.

Mandatory yearly PSA testing at many institutions opened up a gold mine for urologists, who were able to perform lucrative biopsies and prostatectomies on patients who had PSA test numbers above a certain level. However, Ablin has insisted that “routine PSA screening does far more harm to men than good.” Moreover, he maintains that the medical people involved in prostate screening and treatment represent “a self-perpetuating industry that has maimed millions of American men.”

Even during approval hearings for the PSA test, the FDA was well aware of the problems and dangers. For one thing, the test has a 78% false positive rate. An elevated PSA level can be caused by various factors besides cancer, so it is not really a test for prostate cancer. Moreover, a PSA test score can spur frightened men into getting unnecessary biopsies and harmful surgical procedures.

One person who understood the potential dangers of the test well was the chairman of the FDA’s committee, Dr. Harold Markovitz, who decided whether to approve it. He declared, “I’m afraid of this test. If it is approved, it comes out with the imprimatur of the committee…as pointed out, you can’t wash your hands of guilt. . .all this does is threaten a whole lot of men with prostate biopsy…it’s dangerous.”

In the end, the committee did not give unqualified approval to the PSA test but only approved it “with conditions.” However, subsequently, the conditions were ignored.

Nevertheless, the PSA test became celebrated as the route to salvation from prostate cancer. The Postal Service even circulated a stamp promoting yearly PSA tests in 1999. Quite a few people became wealthy and well-known at the Hybritech company, thanks to the Tandem-R PSA test, their most lucrative product.

In those days, the corrupting influence of the pharmaceutical companies on the medical device and drug approval process was already apparent. In an editorial for the Journal of the American Medical Association (quoted in Albin and Piana’s book), Dr. Marcia Angell wrote, “The pharmaceutical industry has gained unprecedented control over the evaluation of its products…there’s mounting evidence that they skew the research they sponsor to make their drugs look better and safer.” She also authored the book The Truth About the Drug Companies: How They Deceive Us and What to Do About It.

A cancer diagnosis often causes great anxiety, but in actuality, prostate cancer develops very slowly compared to other cancers and does not often pose an imminent threat to life. A chart featured in Scholz and Blum’s book compares the average length of life of people whose cancer returns after surgery. In the case of colon cancer, they live on average two more years, but prostate cancer patients live another 18.5 years.

In the overwhelming majority of cases, prostate cancer patients do not die from it but rather from something else, whether they are treated for it or not. In a 2023 article about this issue titled “To Treat or Not to Treat,” the author reports the results of a 15-year study of prostate cancer patients in the New England Journal of Medicine. Only 3% of the men in the study died of prostate cancer, and getting radiation or surgery for it did not seem to offer much statistical benefit over “active surveillance.”

Dr. Scholz confirms this, writing that “studies indicate that these treatments [radiation and surgery] reduce mortality in men with Low and Intermediate-Risk disease by only 1% to 2% and by less than 10% in men with High-Risk disease.”

Nowadays prostate surgery is a dangerous treatment choice, but it is still widely recommended by doctors, especially in Japan. Sadly, it also seems to be unnecessary. One study cited in Ablin and Piana’s book concluded that “PSA mass screening resulted in a huge increase in the number of radical prostatectomies. There is little evidence for improved survival outcomes in the recent years…”

However, a number of urologists urge their patients not to wait to get prostate surgery, threatening them with imminent death if they do not. Ralph Blum, a prostate cancer patient, was told by one urologist, “Without surgery you’ll be dead in two years.” Many will recall that similar death threats were also a common feature of Covid mRNA-injection promotion.

Weighing against prostate surgery are various risks, including death and long-term impairment, since it is a very difficult procedure, even with newer robotic technology. According to Dr. Scholz, about 1 in 600 prostate surgeries result in the death of the patient. Much higher percentages suffer from incontinence (15% to 20%) and impotence after surgery. The psychological impact of these side effects is not a minor problem for many men.

In light of the significant risks and little proven benefit of treatment, Dr. Scholz censures “the urology world’s persistent overtreatment mindset.” Clearly, excessive PSA screening led to inflicting unnecessary suffering on many men. More recently, the Covid phenomenon has been an even more dramatic case of medical overkill.

Ablin and Piana’s book makes an observation that also sheds a harsh light on the Covid medical response: “Isn’t cutting edge innovation that brings new medical technology to the market a good thing for health-care consumers? The answer is yes, but only if new technologies entering the market have proven benefit over the ones they replace.”

That last point especially applies to Japan right now, where people are being urged to receive the next-generation mRNA innovation–the self-amplifying mRNA Covid vaccine. Thankfully, a number seem to be resisting this time.

Addictions

Canada must make public order a priority again

A Toronto park

Public disorder has cities crying out for help. The solution cannot simply be to expand our public institutions’ crisis services

[This editorial was originally published by Canadian Affairs and has been republished with permission]

This week, Canada’s largest public transit system, the Toronto Transit Commission, announced it would be stationing crisis worker teams directly on subway platforms to improve public safety.

Last week, Canada’s largest library, the Toronto Public Library, announced it would be increasing the number of branches that offer crisis and social support services. This builds on a 2023 pilot project between the library and Toronto’s Gerstein Crisis Centre to service people experiencing mental health, substance abuse and other issues.

The move “only made sense,” Amanda French, the manager of social development at Toronto Public Library, told CBC.

Does it, though?

Over the past decade, public institutions — our libraries, parks, transit systems, hospitals and city centres — have steadily increased the resources they devote to servicing the homeless, mentally ill and drug addicted. In many cases, this has come at the expense of serving the groups these spaces were intended to serve.

For some communities, it is all becoming too much.

Recently, some cities have taken the extraordinary step of calling states of emergency over the public disorder in their communities. This September, both Barrie, Ont. and Smithers, B.C. did so, citing the public disorder caused by open drug use, encampments, theft and violence.

In June, Williams Lake, B.C., did the same. It was planning to “bring in an 11 p.m. curfew and was exploring involuntary detention when the province directed an expert task force to enter the city,” The Globe and Mail reported last week.

These cries for help — which Canadian Affairs has also reported on in Toronto, Ottawa and Nanaimo — must be taken seriously. The solution cannot simply be more of the same — to further expand public institutions’ crisis services while neglecting their core purposes and clientele.

Canada must make public order a priority again.

Without public order, Canadians will increasingly cease to patronize the public institutions that make communities welcoming and vibrant. Businesses will increasingly close up shop in city centres. This will accelerate community decline, creating a vicious downward spiral.

We do not pretend to have the answers for how best to restore public order while also addressing the very real needs of individuals struggling with homelessness, mental illness and addiction.

But we can offer a few observations.

First, Canadians must be willing to critically examine our policies.

Harm-reduction policies — which correlate with the rise of public disorder — should be at the top of the list.

The aim of these policies is to reduce the harms associated with drug use, such as overdose or infection. They were intended to be introduced alongside investments in other social supports, such as recovery.

But unlike Portugal, which prioritized treatment alongside harm reduction, Canada failed to make these investments. For this and other reasons, many experts now say our harm-reduction policies are not working.

“Many of my addiction medicine colleagues have stopped prescribing ‘safe supply’ hydromorphone to their patients because of the high rates of diversion … and lack of efficacy in stabilizing the substance use disorder (sometimes worsening it),” Dr. Launette Rieb, a clinical associate professor at the University of British Columbia and addiction medicine specialist recently told Canadian Affairs.

Yet, despite such damning claims, some Canadians remain closed to the possibility that these policies may need to change. Worse, some foster a climate that penalizes dissent.

“Many doctors who initially supported ‘safe supply’ no longer provide it but do not wish to talk about it publicly for fear of reprisals,” Rieb said.

Second, Canadians must look abroad — well beyond the United States — for policy alternatives.

As The Globe and Mail reported in August, Canada and the U.S. have been far harder hit by the drug crisis than European countries.

The article points to a host of potential factors, spanning everything from doctors’ prescribing practices to drug trade flows to drug laws and enforcement.

For example, unlike Canada, most of Europe has not legalized cannabis, the article says. European countries also enforce their drug laws more rigorously.

“According to the UN, Europe arrests, prosecutes and convicts people for drug-related offences at a much higher rate than that of the Americas,” it says.

Addiction treatment rates also vary.

“According to the latest data from the UN, 28 per cent of people with drug use disorders in Europe received treatment. In contrast, only 9 per cent of those with drug use disorders in the Americas received treatment.”

And then there is harm reduction. No other country went “whole hog” on harm reduction the way Canada did, one professor told The Globe.

If we want public order, we should look to the countries that are orderly and identify what makes them different — in a good way.

There is no shame in copying good policies. There should be shame in sticking with failed ones due to ideology.

Our content is always free – but if you want to help us commission more high-quality journalism,

consider getting a voluntary paid subscription.

Business

Canada’s health-care system is not ‘free’—and we’re not getting good value for our money

From the Fraser Institute

By Nadeem Esmail and Mackenzie Moir

In 2025, many Canadians still talk about our “free” health-care system. But in reality, through taxes, we pay a lot for health care. In fact, according to the latest data, a typical Canadian family will pay $19,060 (or about 24 per cent of their total tax bill) for health care this year.

Given the size of that bill, it’s worth asking—do Canadians get good value for all those tax dollars? Not even close.

First, Canadians endure some of the longest wait times for medical care—including primary care, specialist consultations and non-emergency surgery—among developed countries with universal health care. In fact, the wait in Canada for non-emergency care is now more than seven months from referral to treatment, which is more than three times longer than in 1993 when wait times were first measured nationally.

Why the delays?

Part of the reason is the limited number of medical resources available to Canadians. Compared to our universal health-care peers, Canada had some of the fewest physicians, hospital beds and medical technologies such as MRI machines and CT scanners.

And before you wonder if $19,000 per year isn’t enough money for world-class universal coverage, remember that Canada has one of the most expensive universal health-care systems in the developed world, which means Canadians are among the highest spenders on universal health care yet have some of the worst access to health-care services.

Fortunately, countries such as Switzerland and Australia, which both provide far more timely access to high-quality universal care for similar or even lower cost than Canada, offer lessons for reform. Compared to Canada, both countries allow a larger degree of private-sector involvement and, perhaps more importantly, competition in their universal health-care systems.

In Switzerland, for instance, health insurance coverage is mandatory and provided by independent insurers that compete in a regulated market. Swiss citizens freely choose between insurers (which must accept all applicants) and can even personalize some aspects of their universal insurance policy. Patients also have a choice of hospitals, more than half of which are operated privately and for-profit.

In Australia, citizens can purchase private insurance, which covers the cost of treatment in private hospitals. Higher income Australians are actively encouraged to purchase private health insurance and even have to pay additional taxes if they do not. Some 39 per cent of hospitals in Australia are private and for-profit, providing care to both privately and publicly insured patients.

Vitally, competition between private health-care businesses and entrepreneurs in both countries (and many others including Germany and the Netherlands) has helped create a more cost-effective and accessible universal health-care system. Back here in Canada, the lack of private-sector efficiency, innovation and patient-focus has led to the opposite—namely, long waits and poor access.

Health care in Canada is not free. It comes with a substantial price tag through our tax system. And the size of that bill leaves less money for savings and other things families need.

Getting better value for our health-care tax dollars, and solving the longstanding access problems patients face, requires policy reform with a more contemporary understanding of how to structure a truly world-class universal health-care system. Until that reform happens, Canadians will continue to be stuck with a big bill for lousy access to health care.

-

National2 days ago

National2 days agoCanada’s birth rate plummets to an all-time low

-

Alberta1 day ago

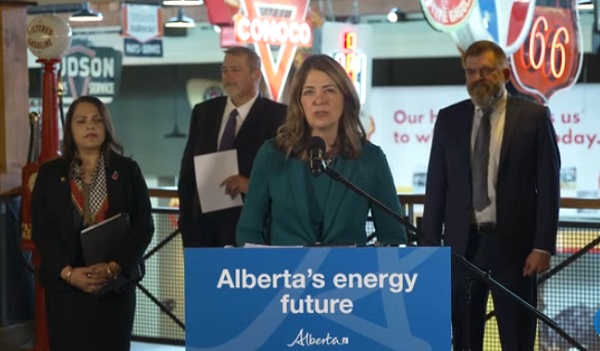

Alberta1 day agoAlberta Takes The Lead: With no company willing to spearhead a new pipeline under federal restrictions, Danielle Smith grabs the reins

-

illegal immigration2 days ago

illegal immigration2 days agoIreland to pay migrant families €10,000 to drop asylum claims, leave country

-

espionage2 days ago

espionage2 days agoNorth Americans are becoming numb to surveillance.

-

Crime2 days ago

Crime2 days agoPierre Poilievre says Christians may be ‘number one’ target of hate violence in Canada

-

International1 day ago

International1 day agoNetanyahu hails TikTok takeover as Israel’s new ‘weapon’ in information war

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoElon Musk announces ‘Grokipedia’ project after Tucker Carlson highlights Wikipedia bias

-

Bruce Dowbiggin1 day ago

Bruce Dowbiggin1 day agoThe McDavid Dilemma: Edmonton Faces Another Big Mess