Frontier Centre for Public Policy

New Book Warns The Decline In Marriage Comes At A High Cost

From the Frontier Centre for Public Policy

Travis Smith reviews I… Do? by Andrea Mrozek and Peter Jon Mitchell, showing that marriage is a public good, not just private choice, arguing culture, not politics, must lead any revival of this vital institution.

Andrea Mrozek and Peter Jon Mitchell, in I… Do?, write that the fading value of marriage is a threat to social stability

I… Do? by Andrea Mrozek and Peter Jon Mitchell manages to say something both obvious and radical: marriage matters. And not just for sentimental reasons. Marriage is a public good, the authors attest.

The book is a modestly sized but extensively researched work that compiles decades of social science data to make one central point: stable marriages improve individual and societal well-being. Married people are generally healthier, wealthier and more resilient. Children from married-parent homes do better across almost every major indicator: academic success, mental health, future earnings and reduced contact with the justice system.

The authors refer to this consistent pattern as the “marriage advantage.” It’s not simply about income. Even in low-income households, children raised by married parents tend to outperform their peers from single-parent families. Mrozek and Mitchell make the case that marriage functions as a stabilizing institution, producing better outcomes not just for couples and kids but for communities and, by extension, the country.

While the book compiles an impressive array of empirical findings, it is clear the authors know that data alone can’t fix what’s broken. There’s a quiet but important concession in these pages: if statistics alone could persuade people to value marriage, we would already be seeing a turnaround.

Marriage in Canada is in sharp decline. Fewer people are getting married, the average age of first marriage continues to climb, and fertility rates are hitting historic lows. The cultural narrative has shifted. Marriage is seen less as a cornerstone of adult life and more as a personal lifestyle choice, often put off indefinitely while people wait to feel ready, build their careers or find emotional stability.

The real value of I… Do? lies in its recognition that the solutions are not primarily political. Policy changes might help stop making things worse, but politicians are not going to rescue marriage. In fact, asking them to may be counterproductive. Looking to politicians to save marriage would involve misunderstanding both marriage and politics. Mrozek and Mitchell suggest the best the state can do is remove disincentives, such as tax policies and benefit structures that inadvertently penalize marriage, and otherwise get out of the way.

The liberal tradition once understood that family should be considered prior to politics for good reason. Love is higher than justice, and the relationships based in it should be kept safely outside the grasp of bureaucrats, ideologues, and power-seekers. The more marriage has been politicized over recent decades, the more it has been reshaped in ways that promote dependency on the impersonal and depersonalizing benefactions of the state.

The book takes a brief detour into the politics of same-sex marriage. Mrozek laments that the topic has become politically untouchable. I would argue that revisiting that battle is neither advisable nor desirable. By now, most Canadians likely know same-sex couples whose marriages demonstrate the same qualities and advantages the authors otherwise praise.

Where I… Do? really shines is in its final section. After pages of statistics, the authors turn to something far more powerful: culture. They explore how civil society—including faith communities, neighbourhoods, voluntary associations and the arts can help revive a vision of marriage that is compelling, accessible and rooted in human experience. They point to storytelling, mentorship and personal witness as ways to rebuild a marriage culture from the ground up.

It’s here that the book moves from description to inspiration. Mrozek and Mitchell acknowledge the limits of top-down efforts and instead offer the beginnings of a grassroots roadmap. Their suggestions are tentative but important: showcase healthy marriages, celebrate commitment and encourage institutions to support rather than undermine families.

This is not a utopian manifesto. It’s a realistic, often sobering look at how far marriage has fallen off the public radar and what it might take to put it back. In a political climate where even mentioning marriage as a public good can raise eyebrows, I… Do? attempts to reframe the conversation.

To be clear, this is not a book for policy wonks or ideologues. It’s for parents, educators, community leaders and anyone concerned about social cohesion. It’s for Gen Xers wondering if their children will ever give them grandchildren. It’s for Gen Zers wondering if marriage is still worth it. And it’s for those in between, hoping to build something lasting in a culture that too often encourages the opposite.

If your experiences already tell you that strong, healthy marriages are among the greatest of human goods, I… Do? will affirm what you know. If you’re skeptical, it won’t convert you overnight, but it might spark a much-needed conversation.

Travis D. Smith is an associate professor of political science at Concordia University in Montreal. This book review was submitted by the Frontier Centre for Public Policy.

Agriculture

Farmers Take The Hit While Biofuel Companies Cash In

From the Frontier Centre for Public Policy

Canada’s emissions policy rewards biofuels but punishes the people who grow our food

In the global rush to decarbonize, agriculture faces a contradictory narrative: livestock emissions are condemned as climate threats, while the same crops turned into biofuels are praised as green solutions argues senior fellow Dr. Joseph Fournier. This double standard ignores the natural carbon cycle and the fossil-fuel foundations of modern farming, penalizing food producers while rewarding biofuel makers through skewed carbon accounting and misguided policy incentives.

In the rush to decarbonize our world, agriculture finds itself caught in a bizarre contradiction.

Policymakers and environmental advocates decry methane and carbon dioxide emissions from livestock digestion, respiration and manure decay, labelling them urgent climate threats. Yet they celebrate the same corn and canola crops when diverted to ethanol and biodiesel as heroic offsets against fossil fuels.

Biofuels are good, but food is bad.

This double standard isn’t just inconsistent—it backfires. It ignores the full life cycle of the agricultural sector’s methane and carbon dioxide emissions and the historical reality that modern farming’s productivity owes its existence to hydrocarbons. It’s time to confront these hypocrisies head-on, or we risk chasing illusory credits while penalizing the very system that feeds us.

Let’s take Canada as an example.

It’s estimated that our agriculture sector emits 69 megatonnes (Mt) of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) annually, or 10 per cent of national totals. Around 35 Mt comes from livestock digestion and respiration, including methane produced during digestion and carbon dioxide released through breathing. Manure composting adds another 12 Mt through methane and nitrous oxide.

Even crop residue decomposition is counted in emissions estimates.

Animal digestion and respiration, including burping and flatulence, and the composting of their waste are treated as industrial-scale pollutants.

These aren’t fossil emissions—they’re part of the natural carbon cycle, where last year’s stover or straw returns to the atmosphere after feeding soil life. Yet under United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) guidelines adopted by Canada, they’re lumped into “agricultural sources,” making farmers look like climate offenders for doing their job.

Ironically, only 21 per cent—about 14 Mt—of the sector’s emissions come from actual fossil fuel use on the farm.

This inconsistency becomes even more apparent in the case of biofuels.

Feed the corn to cows, and its digestive gases count as a planetary liability. Turn it into ethanol, and suddenly it’s an offset.

Canada’s Clean Fuel Regulations (CFR) mandate a 15 per cent CO2e intensity drop by 2030 using biofuels. In this program, biofuel producers earn offset credits per litre, which become a major part of their revenue, alongside fuel sales.

Critics argue the CFR is essentially a second carbon tax, expected to add up to 17 cents per litre at the pump by 2030, with no consumer rebate this time.

But here’s the rub: crop residue emits carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide whether the grain goes to fuel or food.

Diverting crops to biofuels doesn’t erase these emissions: it just shifts the accounting, rewarding biofuel producers with credits while farmers and ranchers take the emissions hit.

These aren’t theoretical concerns: they’re baked into policy.

If ethanol and biodiesel truly offset emissions, why penalize the same crops when used to feed livestock?

And why penalize farmers for crop residue decomposition while ignoring the emissions from rotting leaves, trees and grass in nature?

This contradiction stems from flawed assumptions and bad math.

Fossil fuels are often blamed, while the agricultural sector’s natural carbon loop is treated like a threat. Policy seems more interested in pinning blame than in understanding how food systems actually work.

This disconnect isn’t new—it’s embedded in the history of agriculture.

Since the Industrial Revolution, mechanization and hydrocarbons have driven abundance. The seed drill and reaper slashed labour needs. Tractors replaced horses, boosting output and reducing the workforce.

Yields exploded with synthetic fertilizers produced from methane and other hydrocarbons.

For every farm worker replaced, a barrel of oil stepped in.

A single modern tractor holds the energy equivalent of 50 to 100 barrels of oil, powering ploughing, planting and harvesting that once relied on sweat and oxen.

We’ve traded human labour for hydrocarbons, feeding billions in the process.

Biofuel offsets claim to reduce this dependence. But by subsidizing crop diversion, they deepen it; more corn for ethanol means more diesel for tractors.

It’s a policy trap: vilify farmers to fund green incentives, all while ignoring the fact that oil props up the table we eat from.

Policymakers must scrap the double standards, adopt full-cycle biogenic accounting, and invest in truly regenerative technologies or lift the emissions burden off farmers entirely.

Dr. Joseph Fournier is a senior fellow at the Frontier Centre for Public Policy. An accomplished scientist and former energy executive, he holds graduate training in chemical physics and has written more than 100 articles on energy, environment and climate science.

Frontier Centre for Public Policy

Notwithstanding Clause Is Democracy’s Last Line Of Defence

From the Frontier Centre for Public Policy

Amid radical rulings like Cowichan, Section 33 remains a vital tool for protecting property rights, social and economic stability, and legislative sovereignty in Canada.

The Notwithstanding Clause reminds Canadians that voters, not judges, make the final call

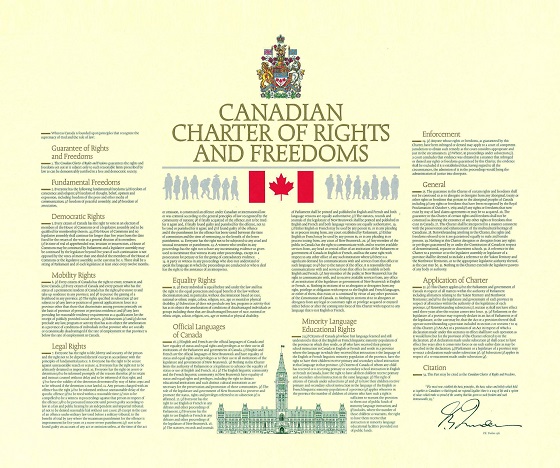

Alberta Premier Danielle Smith recently invoked Section 33 of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms to end a teachers’ strike and prevent endless litigation. The Alberta Teachers’ Association and the provincial NDP have called it tyranny. But a government using lawful authority is not tyranny.

Section 33, known as the “Notwithstanding Clause,” is a constitutional safeguard. It allows legislatures to pass laws that override certain Charter rights for up to five years. It was built into the Charter deliberately to ensure that elected representatives, not judges, remain supreme on fundamental issues.

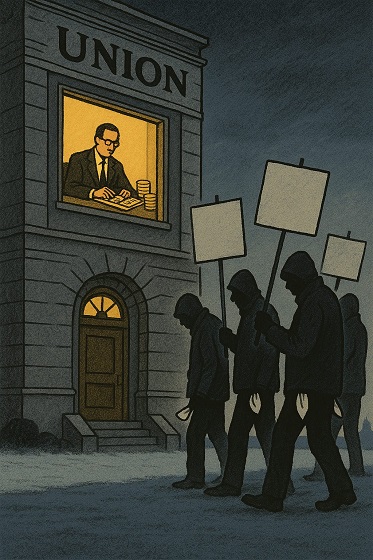

The modern Left despises this clause because it breaks their playbook. When they cannot win in Parliament, they turn to the courts. For 50 years, judges have helped them shift policy by interpreting rights creatively. Section 33 blocks that route. That is why they hate it.

They smear it as a tool of the far right. The facts say otherwise. Allan Blakeney, the Saskatchewan NDP premier, helped enshrine it in 1982. The Parti Québécois, under René Lévesque, at the time the most leftist government in Canada, made heavy use of it. They understood something their successors pretend to forget: democracy rests with voters, not with the judiciary, with all due respect to the judiciary.

Blakeney and Alberta’s Peter Lougheed saw the danger. Federally appointed judges, immune from electoral consequence, could render decisions that uproot regional jurisdiction. Section 33 was the firewall. It recognized that while courts serve justice, legislatures serve people.

Two recent rulings show why that firewall matters. First, the Supreme Court struck down mandatory minimum sentences for child pornography in a 5-4 ruling.

Weeks earlier, in August 2025, Justice Barbara Young of the B.C. Supreme Court ruled that the Cowichan Tribes held unextinguished Aboriginal title to nearly 2,000 acres in Richmond, B.C. That land includes homes, businesses, public utilities and Crown land. The court declared Indigenous title overrides existing property rights, even without treaties or compensation.

The ruling makes every deed in that area, many of which were granted by the Crown over a century ago, subject to Justice Young’s retroactive reinterpretation. Your mortgage may rest on land you no longer legally own. Your lease may be invalid. Your development project unsellable. This is not a theory. It is a ruling.

No economy can function under such uncertainty. Property rights are foundational to free markets. If land ownership depends on a judge’s view of historical use, markets freeze. Banks will not lend. Builders will not build. The Cowichan decision casts a shadow over every titled parcel in British Columbia. Its precedent will not stay local.

B.C. Premier David Eby has chosen to appeal but that will take years. Meanwhile, risk deepens. Capital flees from uncertainty. No investor waits patiently while the Supreme Court ponders first principles.

This is the moment Section 33 was designed for. Its use would freeze the legal effect of Cowichan while legislatures restore order. If the prime minister will not act, others must. Premiers should signal now that property rights will be upheld. If not, the chaos of one courtroom may become a national affliction.

The Cowichan ruling, for all its disruption, may be a clarifying gift. It shows Canadians what radical judicial overreach looks like. Even those who trust the courts may now see why elected governments need the power to say: enough.

Blakeney put it plainly: “What matters is who makes the choices. I would be happy if legislatures gave courts all the deference, as long as legislatures were free to make the major governmental decisions.”

That freedom must now be used. Section 33 is not an act of aggression. It is the return of decision-making to where it belongs. In the aftermath of Cowichan, the country cannot wait years while property confidence erodes.

Section 33 is the remedy.

Marco Navarro-Genie is vice-president of research at the Frontier Centre for Public Policy and co-author, with Barry Cooper, of Canada’s COVID: The Story of a Pandemic Moral Panic (2023).

-

Energy2 days ago

Energy2 days agoCarney bets on LNG, Alberta doubles down on oil

-

Alberta2 days ago

Alberta2 days agoAlberta on right path to better health care

-

Indigenous2 days ago

Indigenous2 days agoTop constitutional lawyer slams Indigenous land ruling as threat to Canadian property rights

-

Alberta2 days ago

Alberta2 days agoCarney government’s anti-oil sentiment no longer in doubt

-

Alberta1 day ago

Alberta1 day ago‘Weird and wonderful’ wells are boosting oil production in Alberta and Saskatchewan

-

Alberta2 days ago

Alberta2 days agoAlberta Emergency Alert test – Wednesday at 1:55 PM

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoCanada is failing dismally at our climate goals. We’re also ruining our economy.

-

Health2 days ago

Health2 days agoSPARC Kindness Tree: A Growing Tradition in Capstone