National

Medical Assistance in Dying now accounts for over 4% of deaths in Canada

The following are interesting statistics pulled directly from the:

Fourth annual report on Medical Assistance in Dying in Canada 2022

Growth in the number of medically assisted deaths in Canada continues in 2022.

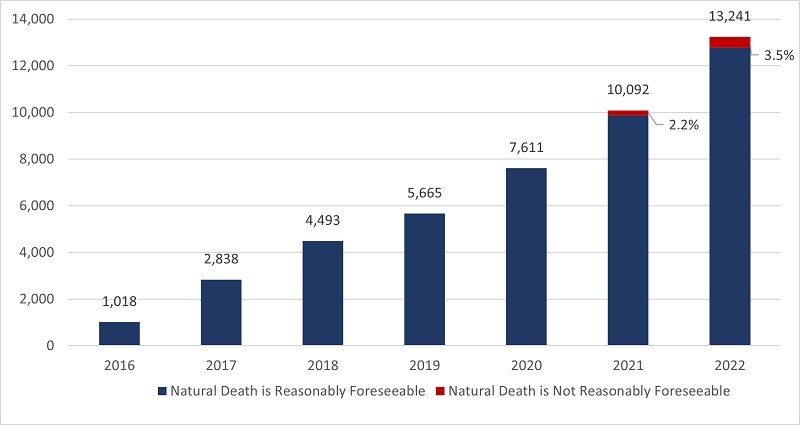

- In 2022, there were 13,241 MAID provisions reported in Canada, accounting for 4.1% of all deaths in Canada.

- The number of cases of MAID in 2022 represents a growth rate of 31.2% over 2021. All provinces except Manitoba and the Yukon continue to experience a steady year-over-year growth in 2022.

- When all data sources are considered, the total number of medically assisted deaths reported in Canada since the introduction of federal MAID legislation in 2016 is 44,958.

Profile of MAID recipients

- In 2022, a slightly larger proportion of males (51.4%) than females (48.6%) received MAID. This result is consistent with 2021 (52.3% males and 47.7% females), 2020 (51.9% males and 48.1% females) and 2019 (50.9% males and 49.1% females).

- The average age of individuals at the time MAID was provided in 2022 was 77.0 years. This average age is slightly higher than the averages of 2019 (75.2), 2020 (75.3) and 2021 (76.3). The average age of females during 2022 was 77.9, compared to males at 76.1.

- Cancer (63.0%) is the most cited underlying medical condition among MAID provisions in 2022, down from 65.6% in 2021 and from a high of 69.1% in 2020. This is followed by cardiovascular conditions (18.8%), other conditions (14.9%), respiratory conditions (13.2%) and neurological conditions (12.6%).

- In 2022, 3.5% of the total number of MAID provisions (463 individuals), were individuals whose natural deaths were not reasonably foreseeable. This is an increase from 2.2% in 2021 (223 individuals). The most cited underlying medical condition for this population was neurological (50.0%), followed by other conditions (37.1%), and multiple comorbidities (23.5%), which is similar to 2021 results. The average age of individuals receiving MAID whose natural death was not reasonably foreseeable was 73.1 years, slightly higher than 70.1 in 2021 but lower than the average age of 77.0 for all MAID recipients in 2022.

Nature of suffering among MAID recipients

- In 2022, the most commonly cited sources of suffering by individuals requesting MAID were the loss of ability to engage in meaningful activities (86.3%), followed by loss of ability to perform activities of daily living (81.9%) and inadequate control of pain, or concern about controlling pain (59.2%).

- These results continue to mirror very similar trends seen in the previous three years (2019 to 2021), indicating that the nature of suffering that leads a person to request MAID has remained consistent over the past four years.

Eligibility Criteria

- Request MAID voluntarily

- 18 years of age or older

- Capacity to make health care decisions

- Must provide informed consent

- Eligible for publicly funded health care services in Canada

- Diagnosed with a “grievous and irremediable medical condition,” where a person must meet all of the following criteria:

- serious and incurable illness, disease or disability

- advanced state of irreversible decline in capability,

- experiencing enduring physical or psychological suffering that is caused by their illness, disease or disability or by the advanced state of decline in capability, that is intolerable to them and that cannot be relieved under conditions that they consider acceptable

- Mental Illness as sole underlying medical condition is excluded until March 17, 2024

3.1 Number of Reported MAID Deaths in Canada (2016 to 2022)

2022 marks six and a half years of access to MAID in Canada. In 2022, there were 13,241 MAID provisions in Canada, bringing the total number of medically assisted deaths in Canada since 2016 to 44,958. In 2022, the total number of MAID provisions increased by 31.2% (2022 over 2021) compared to 32.6% (2021 over 2020). The annual growth rate in MAID provisions has been steady over the past six years, with an average growth rate of 31.1% from 2019 to 2022.

Access to MAID for individuals whose deaths were not reasonably foreseeable marked its second year of eligibility in 2022. In Canada, eligibility for individuals whose death is not reasonably foreseeable began on March 17, 2021, after the passage of the new legislation.Footnote8 There were 463 MAID provisions for persons whose natural death was not reasonably foreseeable, representing 3.5% of all MAID deaths in 2022. This is just over twice the total number of provisions for individuals where natural death was not reasonably foreseeable in 2021 (223 provisions representing 2.2% of all MAID provisions in 2021). Table 3.1 represents total MAID provisions in Canada from 2016 to 2022, including provisions for individuals where natural death was not reasonably foreseeable.

All jurisdictions, except Manitoba and Yukon, experienced growth in MAID provisions in 2022. The highest percentage year over year increases occurred in Québec (45.5%), Alberta (40.7%), Newfoundland and Labrador (38.5%), Ontario (26.8%) and British Columbia (23.9%). Nova Scotia (11.8%), Prince Edward Island (7.3%) and Saskatchewan (4.0%) had lower growth rates. The Yukon remained at the same level as 2021, while Manitoba was the only jurisdiction to experience a decline in MAID provisions for 2022 (-9.0%).

| MAID | NL | PE | NS | NB | QC | ON | MB | SK | AB | BC | YT | NT | NU | Canada |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | – | – | 24 | 9 | 494 | 191 | 24 | 11 | 63 | 194 | – | – | – | 1,018 |

| 2017 | – | – | 62 | 49 | 853 | 839 | 63 | 57 | 205 | 677 | – | – | – | 2,838 |

| 2018 | 23 | 8 | 126 | 92 | 1,249 | 1,500 | 138 | 85 | 307 | 951 | 12 | – | – | 4,493 |

| 2019 | 20 | 20 | 147 | 141 | 1,604 | 1,788 | 177 | 97 | 377 | 1,280 | 13 | – | – | 5,665 |

| 2020 | 49 | 37 | 190 | 160 | 2,278 | 2,378 | 214 | 160 | 555 | 1,572 | 13 | – | – | 7,611 |

| 2021 | 65 | 41 | 245 | 205 | 3,299 | 3,102 | 245 | 247 | 594 | 2,030 | 16 | – | – | 10,092 |

| 2022 | 90 | 44 | 274 | 247 | 4,801 | 3,934 | 223 | 257 | 836 | 2,515 | 16 | – | – | 13,241 |

| TOTAL 2016-2022 |

267 | 156 | 1,068 | 903 | 14,578 | 13,732 | 1,084 | 914 | 2,937 | 9,219 | 84 | – | – | 44,958 |

3.2 MAID Deaths as a Proportion of Total Deaths in Canada

MAID deaths accounted for 4.1% of all deaths in Canada in 2022, an increase from 3.3% in 2021, 2.5% in 2020 and 2.0% in 2019. In 2022, six jurisdictions continue to experience increases in the number of MAID provisions as a percentage of total deaths, ranging from a low of 1.5% (Newfoundland & Labrador) to a high of 6.6% (Québec). MAID deaths as a percentage of total deaths remained at the same levels as 2021 for Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, and Saskatchewan, while Manitoba experienced a decline in MAID deaths as a percentage of all deaths (from 2.1% in 2021 to 1.8% in 2022). As with each of the three previous years (2019 to 2021), Québec and British Columbia experienced the highest percentage of MAID deaths as a proportion of all deaths within their jurisdiction in 2022 (6.6% and 5.5% respectively), continuing to reflect the socio-political dynamics of these two jurisdictions in the context of MAID.

4.5 Profile of Persons Receiving MAID Whose Natural Death is not Reasonably Foreseeable

2022 marks the second year that MAID for persons whose natural death is not reasonably foreseeable is permitted under the law if all other eligibility criteria are met (Table 1.1). New federal MAID legislation passed on March 17, 2021, created a two-track approach to procedural safeguards for MAID practitioners to follow, based on whether or not a person’s natural death is reasonably foreseeable. This approach to safeguards ensures that sufficient time and expertise are spent assessing MAID requests from persons whose natural death is not reasonably foreseeable. New and enhanced safeguards (Table 1.2), including a minimum 90-day assessment period, seek to address the diverse source of suffering and vulnerability that could potentially lead a person who is not nearing death to ask for MAID and to identify alternatives to MAID that could reduce suffering.

In 2022, 3.5% of MAID recipients (463 individuals) were assessed as not having a reasonably foreseeable natural death, up slightly from 2.2% (223 individuals) in 2021. As a percentage of all MAID deaths in Canada, MAID for individuals whose natural death is not reasonably foreseeable represents just 0.14% of all deaths in Canada in 2022 (compared to all MAID provisions, which represent 4.1% of all 2022 deaths in Canada). The proportion of MAID recipients whose natural death was not reasonably foreseeable continues to remain very small compared to the total number of MAID recipients.

This population of individuals whose natural death was not reasonably foreseeable have a different medical profile than individuals whose death was reasonably foreseeable. As shown in Chart 4.5A, the main underlying medical condition reported in the population whose natural death was not reasonably foreseeable was neurological (50.0%), followed by ‘other condition’ (37.1%), and multiple comorbidities (23.5%). This differs from the main condition (as reported in Chart 4.1A) for all MAID recipients in 2022, where the majority of persons receiving MAID had cancer as a main underlying medical condition (63.0%), followed by cardiovascular conditions (18.8%) and other conditions (14.9%) (such as chronic pain, osteoarthritis, frailty, fibromyalgia, autoimmune conditions). These results are similar to 2021.

Of the MAID provisions for individuals where death was reasonably foreseeable, the majority were individuals ages 71 and older (71.1%) while only 28.9% were between ages 18-70. A similar trend was observed for individuals where natural death was not reasonably foreseeable which also showed a greater percentage of individuals who received MAID being 71 and older (58.5%) and a lower number of MAID provisions for individuals between 18-70 years (41.5%). Overall, however, MAID provisions for individuals whose death is not reasonably foreseeable tended to be in the younger age categories than those where natural death is foreseeable.

Agriculture

Canada’s air quality among the best in the world

From the Fraser Institute

By Annika Segelhorst and Elmira Aliakbari

Canadians care about the environment and breathing clean air. In 2023, the share of Canadians concerned about the state of outdoor air quality was 7 in 10, according to survey results from Abacus Data. Yet Canada outperforms most comparable high-income countries on air quality, suggesting a gap between public perception and empirical reality. Overall, Canada ranks 8th for air quality among 31 high-income countries, according to our recent study published by the Fraser Institute.

A key determinant of air quality is the presence of tiny solid particles and liquid droplets floating in the air, known as particulates. The smallest of these particles, known as fine particulate matter, are especially hazardous, as they can penetrate deep into a person’s lungs, enter the blood stream and harm our health.

Exposure to fine particulate matter stems from both natural and human sources. Natural events such as wildfires, dust storms and volcanic eruptions can release particles into the air that can travel thousands of kilometres. Other sources of particulate pollution originate from human activities such as the combustion of fossil fuels in automobiles and during industrial processes.

The World Health Organization (WHO) and the Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment (CCME) publish air quality guidelines related to health, which we used to measure and rank 31 high-income countries on air quality.

Using data from 2022 (the latest year of consistently available data), our study assessed air quality based on three measures related to particulate pollution: (1) average exposure, (2) share of the population at risk, and (3) estimated health impacts.

The first measure, average exposure, reflects the average level of outdoor particle pollution people are exposed to over a year. Among 31 high-income countries, Canadians had the 5th-lowest average exposure to particulate pollution.

Next, the study considered the proportion of each country’s population that experienced an annual average level of fine particle pollution greater than the WHO’s air quality guideline. Only 2 per cent of Canadians were exposed to fine particle pollution levels exceeding the WHO guideline for annual exposure, ranking 9th of 31 countries. In other words, 98 per cent of Canadians were not exposed to fine particulate pollution levels exceeding health guidelines.

Finally, the study reviewed estimates of illness and mortality associated with fine particle pollution in each country. Canada had the fifth-lowest estimated death and illness burden due to fine particle pollution.

Taken together, the results show that Canada stands out as a global leader on clean air, ranking 8th overall for air quality among high-income countries.

Canada’s record underscores both the progress made in achieving cleaner air and the quality of life our clean air supports.

espionage

Western Campuses Help Build China’s Digital Dragnet With U.S. Tax Funds, Study Warns

Shared Labs, Shared Harm names MIT, Oxford and McGill among universities working with Beijing-backed AI institutes linked to Uyghur repression and China’s security services.

Over the past five years, some of the world’s most technologically advanced campuses in the United States, Canada and the United Kingdom — including MIT, Oxford and McGill — have relied on taxpayer funding while collaborating with artificial-intelligence labs embedded in Beijing’s security state, including one tied to China’s mass detention of Uyghurs and to the Ministry of Public Security, which has been accused of targeting Chinese dissidents abroad.

That is the core finding of Shared Labs, Shared Harm, a new report from New York–based risk firm Strategy Risks and the Human Rights Foundation. After reviewing tens of thousands of scientific papers and grant records, the authors conclude that Western public funds have repeatedly underwritten joint work between elite universities and two Chinese “state-priority” laboratories whose technologies drive China’s domestic surveillance machinery — an apparatus that, a recent U.S. Congressional threat assessment warns, is increasingly being turned outward against critics in democratic states.

The key Chinese collaborators profiled in the study are closely intertwined with China’s security services. One of the two featured labs is led by a senior scientist from China Electronics Technology Group Corporation (CETC), the sanctioned conglomerate behind the platform used to flag and detain Uyghurs in Xinjiang; the other has hosted “AI + public security” exchanges with the Ministry of Public Security’s Third Research Institute, the bureau responsible for technical surveillance and digital forensics.

The report’s message is blunt: even as governments scramble to stop technology transfer on the hardware side, open academic science has quietly been supplying Chinese security organs with new tools to track bodies, faces and movements at scale.

It lands just as Washington and its allies move to tighten controls on advanced chips and AI exports to China. In the Netherlands’ Nexperia case, the Dutch government invoked a rarely used Cold War–era emergency law this fall to take temporary control of a Chinese-owned chipmaker and block key production from being shifted to China — prompting a furious response from Beijing, and supply shocks that rippled through European automakers.

“The Chinese Communist Party uses security and national security frameworks as tools for control, censorship, and suppressing dissenting views, transforming technical systems into instruments of repression,” the report says. “Western institutions lend credibility, knowledge, and resources to Chinese laboratories supporting the country’s surveillance and defense ecosystem. Without safeguards … publicly funded research will continue to support organizations that contribute to repression in China.”

Cameras and Drones

The Strategy Risks team focuses on two state-backed institutes: Zhejiang Lab, a vast AI and high-performance computing campus founded by the Zhejiang provincial government with Alibaba and Zhejiang University, and the Shanghai Artificial Intelligence Research Institute (SAIRI), now led by a senior CETC scientist. CETC designed the Integrated Joint Operations Platform, or IJOP — the data system that hoovered up phone records, biometric profiles and checkpoint scans to flag “suspicious” people in Xinjiang.

United Nations investigators and several Western governments have concluded that IJOP and related systems supported mass surveillance, detention and forced-labor campaigns against Uyghurs that amount to crimes against humanity.

Against that backdrop, the scale of Western collaboration is striking.

Since 2020, Zhejiang Lab and SAIRI have published more than 11,000 papers; roughly 3,000 of those had foreign co-authors, many from the United States, United Kingdom, and Canada. About 20 universities are identified as core collaborators, including MIT, Stanford, Harvard, Princeton, Carnegie Mellon, Johns Hopkins, UC Berkeley, Oxford, University College London — and Canadian institutions such as McGill University — along with a cluster of leading European technical universities.

Among the major U.S. public funders acknowledged in these joint papers are the National Science Foundation (NSF), the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the Office of Naval Research (ONR), the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) and the Department of Transportation. For North America, the warning is twofold: U.S. and Canadian universities are far more entangled with China’s security-linked AI labs than most policymakers grasp — and existing “trusted research” frameworks, built around IP theft, are almost blind to the human-rights risk.

In one flagship example, Zhejiang Lab collaborated with MIT on advanced optical phase-shifting — a field central to high-resolution imaging systems used in satellite surveillance, remote sensing and biometric scanning. The paper cited support from a DARPA program, meaning U.S. defense research dollars effectively underwrote joint work with a Chinese lab that partners closely with military universities and the CETC conglomerate behind Xinjiang’s IJOP system.

Carnegie Mellon projects with Zhejiang Lab focused on multi-object tracking and acknowledged funding from the National Science Foundation and the U.S. Office of Naval Research. Multi-object tracking is a backbone technology for modern surveillance — allowing cameras and drones to follow multiple people or vehicles across crowds and city blocks. “In the Chinese context,” the report notes, such capabilities map naturally onto “public security applications such as protest monitoring,” even when the academic papers present them as neutral advances in computer vision.

The report also highlights Zhejiang Lab’s role as an international partner in CAMERA 2.0, a £13-million U.K. initiative on motion capture, gait recognition and “smart cities” anchored at the University of Bath, and its leadership in BioBit, a synthetic-biology and imaging program whose advisory board includes University College London, McGill University, the University of Glasgow and other Western campuses.

Meanwhile, SAIRI has quietly become a hub for AI that blurs public-security, military and commercial lines.

Established in 2018 and run since 2020 by CETC academician Lu Jun — a designer of China’s KJ-2000 airborne early-warning aircraft and a veteran of command-and-control systems — SAIRI specializes in pose estimation, tracking and large-scale imaging.

Under Lu, the institute has deepened ties with firms already sanctioned by Washington for their roles in Xinjiang surveillance. In 2024 it signed cooperation agreements with voice-recognition giant iFlytek and facial-recognition champion SenseTime, as well as CloudWalk and Intellifusion, which market “smart city” policing platforms.

SAIRI also hosted an “AI + public security” exchange with the Ministry of Public Security’s Third Research Institute — the bureau responsible for technical surveillance and digital forensics — and co-developed what Chinese media billed as the country’s first AI-assisted shooting training system. That platform, nominally built for sports, was overseen by a Shanghai government commission that steers AI into defense and public-security applications, raising the prospect of its use in paramilitary or police training.

Outside the lab, MPS officers have been charged in the United States with running online harassment and intimidation schemes targeting Chinese dissidents, and MPS-linked “overseas police service stations” in North America and Europe have been investigated for pressuring exiles and critics to return to China.

Meanwhile, Radio-Canada, drawing on digital records first disclosed to Australian media in 2024 by an alleged Chinese spy, has reported new evidence suggesting that a Chinese dissident who died in a mysterious kayaking accident near Vancouver was being targeted for elimination by MPS officers and agents embedded in a Chinese conglomerate that the U.S. Treasury accuses of running a money-laundering and modern-slavery empire out of Cambodia.

The new reporting focuses on a former undercover agent for Office No. 1 of China’s Ministry of Public Security — the police ministry at the core of so-called “CCP police stations” in global and Canadian cities, and reportedly tasked with hunting dissidents abroad.

Taken together, cases of alleged Chinese “police station” networks operating globally, new U.S. Congressional reports on worldwide threats from the Chinese Communist Party, and the warnings in Shared Labs, Shared Harm suggest that Western universities are not only helping to build China’s domestic repression apparatus with U.S. taxpayer funds, but may also be contributing to global surveillance tools that can be paired with Beijing’s operatives abroad.

To counter this trend, the paper urges a reset in research governance: broaden due diligence to weigh human-rights risk, mandate transparency over all international co-authorships and joint labs, condition partnerships with security-linked institutions on strict safeguards and narrow scopes of work, and strengthen university ethics bodies so they take responsibility for cross-border collaborations.

The Bureau is a reader-supported publication.

To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

-

MAiD1 day ago

MAiD1 day agoFrom Exception to Routine. Why Canada’s State-Assisted Suicide Regime Demands a Human-Rights Review

-

Automotive2 days ago

Automotive2 days agoPower Struggle: Governments start quietly backing away from EV mandates

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoCarney government should privatize airports—then open airline industry to competition

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoNew Chevy ad celebrates marriage, raising children

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoWhat’s Going On With Global Affairs Canada and Their $392 Million Spending Trip to Brazil?

-

Censorship Industrial Complex2 days ago

Censorship Industrial Complex2 days agoA Democracy That Can’t Take A Joke Won’t Tolerate Dissent

-

Energy1 day ago

Energy1 day agoCanada following Europe’s stumble by ignoring energy reality

-

Censorship Industrial Complex2 days ago

Censorship Industrial Complex2 days agoFrances Widdowson’s Arrest Should Alarm Every Canadian