Canadian Energy Centre

Indigenous communities shut out by B.C. tanker ban want another chance

From the Canadian Energy Centre

By Deborah Jaremko and Will Gibson

“Canada’s Indigenous communities need projects, not lawsuits that hold them up”

From the outset, projects must unite leadership from proponents, governments and affected First Nations

The head of the National Coalition of Chiefs (NCC) is calling for the repeal of the oil tanker ban on B.C.’s north coast as Canada seeks “nation-building” projects to strengthen economic independence.

With short shipping times to hungry Asian markets, ports like Prince Rupert or Kitimat offer a strong business case – but only if the tankers can dock.

“No proponent is going to look at investing in a pipeline to the north coast with that kind of legislation in place,” says NCC founder and CEO Dale Swampy.

Formed in 2016, the NCC is a group of pro-development First Nation leaders including some who were equity partners in the cancelled Northern Gateway pipeline from Edmonton to Kitimat.

Canada’s Indigenous communities need projects, not lawsuits that hold them up, he says.

Original map of the proposed Northern Gateway Pipeline, submitted to regulators as part of a preliminary information package in October 2005. Map courtesy Canada Energy Regulator

Northern Gateway and the tanker ban

The tanker ban and Northern Gateway are intrinsically linked.

The moratorium contributed to the loss of Indigenous ownership stakes and an estimated $2 billion in economic opportunity for First Nations and Métis communities.

“We have consistently spoken up against this legislation, which directly affects the ability of our communities to participate in developing resources,” Swampy says.

With the aim to diversify markets for Canadian oil by reaching customers in Asia, Enbridge announced Northern Gateway in 2004.

The project’s 7,800-page regulatory application to the National Energy Board (NEB) – including more than 1,600 pages specific to marine safety – followed in May 2010.

In December 2013, after extensive assessment and public hearings, including with Indigenous communities, a three-member Joint Review Panel from the NEB and the Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency recommended the project to go ahead.

In June 2014, the federal government approved Northern Gateway with 209 conditions, including a requirement to fulfill over 400 voluntary commitments, many tied to marine safety.

After receiving approval, Northern Gateway’s management team and the project’s Aboriginal Equity Partners proposed an increase in Indigenous ownership from 10 per cent to 33 per cent.

They also created a joint governance structure where the communities and the company would have an equal voice.

The modified project would also incorporate First Nations and Métis environmental stewardship and monitoring using traditional science.

Meanwhile, legal actions were underway by environmental groups and Indigenous communities outside the equity partners.

By December 2014, the Federal Court of Appeal had consolidated multiple cases challenging the project’s approval.

Blocking the Northern Gateway pipeline and enacting a moratorium on oil tanker traffic on B.C.’s north coast became cornerstones of the Liberal Party’s 2015 election platform.

In November 2015, just a week after being sworn in, former Prime Minister Justin Trudeau instructed his transport minister to “formalize” the ban, a major setback for Northern Gateway.

Five months later, in June 2016 the Federal Court of Appeal overturned the government’s approval for the project, ruling that Canada had failed to fulfill its constitutional duty to consult Indigenous communities.

In November 2016, Trudeau officially rejected Northern Gateway, devastating hopes for the bands that would have become equity partners.

“Thirty-one of the 40 First Nations and Métis communities who were located on Northern Gateway’s right-of-way supported the pipeline, but a couple of communities backed by environmental groups were able to stop the entire project,” Swampy says.

“That’s not fair or democratic.”

In May 2017, Bill C-48, also known as the Oil Tanker Moratorium Act, was formally introduced in the House of Commons.

Indigenous communities stripped of opportunity

At the time, Swampy told the Financial Post that the communities saw the decision to reject Northern Gateway as political and not acting in the best interests of Canadians.

“They weren’t asked about the financial effect, the lost employment,” he said.

The implications of the tanker ban go far beyond the West Coast, Indian Resources Council CEO Stephen Buffalo told the Standing Senate Committee on Transport and Communications in March 2019.

Buffalo joined Swampy and other Indigenous leaders to speak to the committee as part of its consideration of Bill C-48.

Representing more than 130 First Nations that produce or have the potential to produce oil and gas, he said community prosperity is closely tied to the sector.

“The industry is suffering greatly from the lack of pipeline access…We need access to new markets to obtain fair value for our oil resources,” Buffalo said.

“We are struggling with addictions and depression, and people are losing hope. If we are ever going to make faster progress on these issues, our First Nations communities need more own-source revenues to fund cultural programs, sports programs or health activities for our young people,” he said.

“We need more jobs available for our people. We need them to earn good wages — wages that can support their families. Right now, Bill C-48 and other policies threaten all of that for us.”

Buffalo questioned the necessity of the tanker ban.

“I think all First Nations would support development of strict regulations that protect the environment, but that’s different from arbitrarily stopping just Canadian oil tanker activity,” he said.

The Senate approved the tanker ban and it became law upon Royal Assent on June 21, 2019.

Shifting times and new pipelines

Six years and the threat of U.S. tariffs later, the view on Canadian oil pipelines — and, potentially, the tanker ban itself — is shifting.

Growing public support for pipelines in recent opinion polls has encouraged Swampy.

So, too, has the change in attitudes towards development by coastal First Nations that have experienced the benefits of working with industry.

“Many of the coastal First Nations in northwestern B.C. are either building or looking at building LNG facilities. They appreciate the fact prosperity can be gained by partnering on these projects,” he says.

The NCC wants to see that same opportunity for the communities that would have benefited from Northern Gateway, through a new oil pipeline proposal to either Kitimat or Prince Rupert.

“We are hoping providing some certainty with Indigenous consultation and participation will give proponents some certainty they have a willing partner,” Swampy says.

To avoid lawsuits that delay or cancel projects and drive developers out of Canada, Swampy says agreements must, from the outset, unite leadership from proponents, governments and affected First Nations.

“We hope governments hear our message: we want projects, not lawsuits,” he says.

“Communities don’t need a cheque or a handout. They need the opportunity to participate in a meaningful way.”

Alberta

‘Weird and wonderful’ wells are boosting oil production in Alberta and Saskatchewan

From the Canadian Energy Centre

Multilateral designs lift more energy with a smaller environmental footprint

A “weird and wonderful” drilling innovation in Alberta is helping producers tap more oil and gas at lower cost and with less environmental impact.

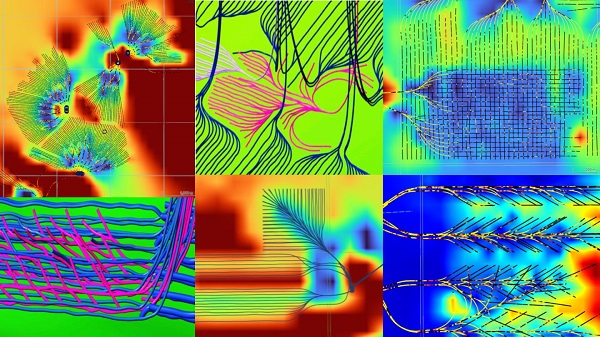

With names like fishbone, fan, comb-over and stingray, “multilateral” wells turn a single wellbore from the surface into multiple horizontal legs underground.

“They do look spectacular, and they are making quite a bit of money for small companies, so there’s a lot of interest from investors,” said Calin Dragoie, vice-president of geoscience with Calgary-based Chinook Consulting Services.

Dragoie, who has extensively studied the use of multilateral wells, said the technology takes horizontal drilling — which itself revolutionized oil and gas production — to the next level.

“It’s something that was not invented in Canada, but was perfected here. And it’s something that I think in the next few years will be exported as a technology to other parts of the world,” he said.

Dragoie’s research found that in 2015 less than 10 per cent of metres drilled in Western Canada came from multilateral wells. By last year, that share had climbed to nearly 60 per cent.

Royalty incentives in Alberta have accelerated the trend, and Saskatchewan has introduced similar policy.

Multilaterals first emerged alongside horizontal drilling in the late 1990s and early 2000s, Dragoie said. But today’s multilaterals are longer, more complex and more productive.

The main play is in Alberta’s Marten Hills region, where producers are using multilaterals to produce shallow heavy oil.

Today’s average multilateral has about 7.5 horizontal legs from a single surface location, up from four or six just a few years ago, Dragoie said.

One record-setting well in Alberta drilled by Tamarack Valley Energy in 2023 features 11 legs stretching two miles each, for a total subsurface reach of 33 kilometres — the longest well in Canada.

By accessing large volumes of oil and gas from a single surface pad, multilaterals reduce land impact by a factor of five to ten compared to conventional wells, he said.

The designs save money by skipping casing strings and cement in each leg, and production is amplified as a result of increased reservoir contact.

Here are examples of multilateral well design. Images courtesy Chinook Consulting Services.

Parallel

Fishbone

Fan

Waffle

Stingray

Frankenwells

Alberta

How economic corridors could shape a stronger Canadian future

Ship containers are stacked at the Panama Canal Balboa port in Panama City, Saturday, Sept. 20, 2025. The Panama Canals is one of the most significant trade infrastructure projects ever built. CP Images photo

From the Canadian Energy Centre

Q&A with Gary Mar, CEO of the Canada West Foundation

Building a stronger Canadian economy depends as much on how we move goods as on what we produce.

Gary Mar, CEO of the Canada West Foundation, says economic corridors — the networks that connect producers, ports and markets — are central to the nation-building projects Canada hopes to realize.

He spoke with CEC about how these corridors work and what needs to change to make more of them a reality.

CEC: What is an economic corridor, and how does it function?

Gary Mar: An economic corridor is a major artery connecting economic actors within a larger system.

Consider the road, rail and pipeline infrastructure connecting B.C. to the rest of Western Canada. This infrastructure is an important economic corridor facilitating the movement of goods, services and people within the country, but it’s also part of the economic corridor connecting western producers and Asian markets.

Economic corridors primarily consist of physical infrastructure and often combine different modes of transportation and facilities to assist the movement of many kinds of goods.

They also include social infrastructure such as policies that facilitate the easy movement of goods like trade agreements and standardized truck weights.

The fundamental purpose of an economic corridor is to make it easier to transport goods. Ultimately, if you can’t move it, you can’t sell it. And if you can’t sell it, you can’t grow your economy.

CEC: Which resources make the strongest case for transport through economic corridors, and why?

Gary Mar: Economic corridors usually move many different types of goods.

Bulk commodities are particularly dependent on economic corridors because of the large volumes that need to be transported.

Some of Canada’s most valuable commodities include oil and gas, agricultural commodities such as wheat and canola, and minerals such as potash.

CEC: How are the benefits of an economic corridor measured?

Gary Mar: The benefits of economic corridors are often measured via trade flows.

For example, the upcoming Roberts Bank Terminal 2 in the Port of Vancouver will increase container trade capacity on Canada’s west coast by more than 30 per cent, enabling the trade of $100 billion in goods annually, primarily to Asian markets.

Corridors can also help make Canadian goods more competitive, increasing profits and market share across numerous industries. Corridors can also decrease the costs of imported goods for Canadian consumers.

For example, after the completion of the Trans Mountain Expansion in May 2024 the price differential between Western Canada Select and West Texas Intermediate narrowed by about US$8 per barrel in part due to increased competition for Canadian oil.

This boosted total industry profits by about 10 per cent, and increased corporate tax revenues to provincial and federal governments by about $3 billion in the pipeline’s first year of operation.

CEC: Where are the most successful examples of these around the world?

Gary Mar: That depends how you define success. The economic corridors transporting the highest value of goods are those used by global superpowers, such as the NAFTA highway that facilitates trade across Canada, the United States and Mexico.

The Suez and Panama canals are two of the most significant trade infrastructure projects ever built, facilitating 12 per cent and five per cent of global trade, respectively. Their success is based on their unique geography.

Canada’s Asia-Pacific Gateway, a coordinated system of ports, rail lines, roads, and border crossings, primarily in B.C., was a highly successful initiative that contributed to a 48 per cent increase in merchandise trade with Asia from $44 million in 2006 to $65 million in 2015.

China’s Belt and Road initiative to develop trade infrastructure in other countries is already transforming global trade. But the project is as much about extending Chinese influence as it is about delivering economic returns.

Piles of coal awaiting export and gantry cranes used to load and unload containers onto and from cargo ships are seen at Deltaport, in Tsawwassen, B.C., on Monday, September 9, 2024. CP Images photo

CEC: What would need to change in Canada in terms of legislation or regulation to make more economic corridors a reality?

Gary Mar: A major regulatory component of economic corridors is eliminating trade barriers.

The federal Free Trade and Labour Mobility in Canada Act is a good start, but more needs to be done at the provincial level to facilitate more internal trade.

Other barriers require coordinated regulatory action, such as harmonizing weight restrictions and road bans to streamline trucking.

By taking a systems-level perspective – convening a national forum where Canadian governments consistently engage on supply chains and trade corridors – we can identify bottlenecks and friction points in our existing transportation networks, and which investments would deliver the greatest return on investment.

-

Alberta13 hours ago

Alberta13 hours agoNational Crisis Approaching Due To The Carney Government’s Centrally Planned Green Economy

-

COVID-191 day ago

COVID-191 day agoNew report warns Ottawa’s ‘nudge’ unit erodes democracy and public trust

-

Agriculture14 hours ago

Agriculture14 hours agoFederal cabinet calls for Canadian bank used primarily by white farmers to be more diverse

-

Great Reset12 hours ago

Great Reset12 hours agoCanadian government forcing doctors to promote euthanasia to patients: report

-

Crime2 days ago

Crime2 days agoHow Global Organized Crime Took Root In Canada

-

Energy2 days ago

Energy2 days agoExpanding Canadian energy production could help lower global emissions

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoThe numbers Canada uses to set policy don’t add up

-

COVID-191 day ago

COVID-191 day agoFreedom Convoy protestor Evan Blackman convicted at retrial even after original trial judge deemed him a “peacemaker”