By Ian Bradbury

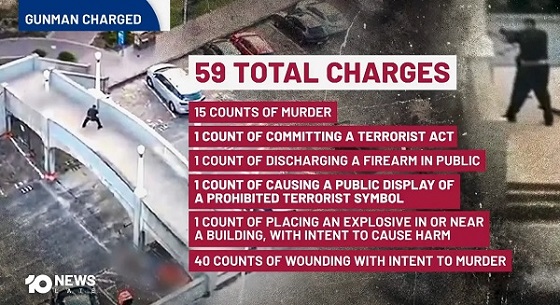

After attacks by Islamic extremists, a familiar pattern follows. Debate erupts. Commentary and interviews flood the media. Op-eds, narratives, talking points, and competing interpretations proliferate in the immediate aftermath of bloodshed. The brief interval since the Bondi beach attack is no exception.

Many of these responses condemn the violence and call for solidarity between Muslims and non-Muslims, as well as for broader societal unity. Their core message is commendable, and I support it: extremist violence is horrific, societies must stand united, and communities most commonly targeted by Islamic extremists—Jews, Christians, non-Muslim minorities, and moderate Muslims—deserve to live in safety and be protected.

Yet many of these info-space engagements miss the mark or cater to a narrow audience of wonks. A recurring concern is that, at some point, many of these engagements suggest, infer, or outright insinuate that non-Muslims, or predominantly non-Muslim societies, are somehow expected or obligated to interpret these attacks through an Islamic or Muslim-impact lens. This framing is frequently reinforced by a familiar “not a true Muslim” narrative regarding the perpetrators, alongside warnings about the risks of Islamophobia.

These misaligned expectations collide with a number of uncomfortable but unavoidable truths. Extremist groups such as ISIS, Al-Qaeda, Hamas, Hezbollah, and decentralized attackers with no formal affiliations have repeatedly and explicitly justified their violence through interpretations of Islamic texts and Islamic history. While most Muslims reject these interpretations, it remains equally true that large, dynamic groups of Muslims worldwide do not—and that these groups are well prepared to, and regularly do, use violence to advance their version of Islam.

Islamic extremist movements do not, and did not, emerge in a vacuum. They draw from the broader Islamic context. This fact is observable, persistent, and cannot be wished or washed away, no matter how hard some may try or many may wish otherwise.

Given this reality, it follows that for most non-Muslims—many of whom do not have detailed knowledge of Islam, its internal theological debates, historical divisions, or political evolution—and for a considerable number of Muslims as well, Islamic extremist violence is perceived as connected to Islam as it manifests globally. This perception persists regardless of nuance, disclaimers, or internal distinctions within the faith and among its followers.

THE COST OF DENIAL AND DEFLECTION

Denying or deflecting from these observable connections prevents society from addressing the central issues following an Islamic extremist attack in a Western country: the fatalities and injuries, how the violence is perceived and experienced by surviving victims, how it is experienced and understood by the majority non-Muslim population, how it is interpreted by non-Muslim governments responsible for public safety, and how it is received by allied nations. Worse, refusing to confront these difficult truths—or branding legitimate concerns as Islamophobia—creates a vacuum, one readily filled by extremist voices and adversarial actors eager to poison and pollute the discussion.

Following such attacks, in addition to thinking first of the direct victims, I sympathize with my Muslim family, friends, colleagues, moderate Muslims worldwide, and Muslim victims of Islamic extremism, particularly given that anti-Muslim bigotry is a real problem they face. For Muslim victims of Islamic extremism, that bigotry constitutes a second blow they must endure. Personal sympathy, however, does not translate into an obligation to center Muslim communal concerns when they were not the targets of the attack. Nor does it impose a public obligation or override how societies can, do, or should process and respond to violence directed at them by Islamic extremists.

As it applies to the general public in Western nations, the principle is simple: there should be no expectation that non-Muslims consider Islam, inter-Islamic identity conflicts, internal theological disputes, or the broader impact on the global Muslim community, when responding to attacks carried out by Islamic extremists. That is, unless Muslims were the victims, in which case some consideration is appropriate.

Quite bluntly, non-Muslims are not required to do so and are entitled to reject and push back against any suggestion that they must or should. Pointedly, they are not Muslims, a fact far too many now seem to overlook.

The arguments presented here will be uncomfortable for many and will likely provoke polarizing discussion. Nonetheless, they articulate an important, human-centered position regarding how Islamic extremist attacks in Western nations are commonly interpreted and understood by non-Muslim majority populations.

Non-Muslims are free to give no consideration to Muslim interests at any time, particularly following an Islamic extremist attack against non-Muslims in a non-Muslim country. The sole exception is that governments retain an obligation to ensure the safety and protection of their Muslim citizens, who face real and heightened threats during these periods. This does not suggest that non-Muslims cannot consider Muslim community members; it simply affirms that they are under no obligation to do so.

The impulse for Muslims to distance moderate Muslims and Islam from extremist attacks—such as the targeting of Jews in Australia or foiled Christmas market plots in Poland and Germany—is understandable.

Muslims do so to protect their own interests, the interests of fellow Muslims, and the reputation of Islam itself. Yet this impulse frequently collapses into the “No True Scotsman” fallacy, pointing to peaceful Muslims as the baseline while asserting that the attackers were not “true Muslims.”

Such claims oversimplify the reality of Islam as it manifests globally and fail to address the legitimate political and social consequences that follow Islamic extremist attacks in predominantly non-Muslim Western societies. These deflections frequently produce unintended effects, such as strengthening anti-Muslim extremist sentiments and movements and undermining efforts to diminish them.

The central issue for public discourse after an Islamic extremist attack is not debating whether the perpetrators were “true” or “false” Muslims, nor assessing downstream impacts on Muslim communities—unless they were the targets.

It is a societal effort to understand why radical ideologies continue to emerge from varying—yet often overlapping—interpretations of Islam, how political struggles within the Muslim world contribute to these ideologies, and how non-Muslim-majority Western countries can realistically and effectively confront and mitigate threats related to Islamic extremism before the next attack occurs and more non-Muslim and Muslim lives are lost.

Addressing these realities directly is the only path toward protecting communities, confronting extremism, and preventing further loss of life.

Ian Bradbury, a global security specialist with over 25 years experience, transitioned from Defence and NatSec roles to found Terra Nova Strategic Management (2009) and 1NAEF (2014). A TEDx, UN, NATO, and Parliament speaker, he focuses on terrorism, hybrid warfare, conflict aid, stability operations, and geo-strategy.

The Bureau is a reader-supported publication.

To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Related