Agriculture

How oil and gas support food security in Canada and around the world

General view of the ‘TD Canadian 4-H Dairy Classic Showmanship’ within the 101st edition of Royal Agricultural Winter Fair at Exhibition Place in Toronto, Ontario, on November 6, 2023. The Royal is the largest combined indoor agriculture fair and international equestrian competition in the world. Getty Images photo

From the Canadian Energy Centre

‘Agriculture requires fuel, and it requires lubricants. It requires heat and electricity. Modern agriculture can’t be done without energy’

Agriculture and oil and gas are two of Canada’s biggest businesses – and they are closely linked, industry leaders say.

From nitrogen-based fertilizer to heating and equipment fuels, oil and gas are the backbone of Canada’s farms, providing food security for Canadians and exports to nearly 200 countries around the world.

“Canada is a country that is rich in natural resources, and we are among the best, I would even characterize as the best, in terms of the production of sustainable energy and food, not only for Canadians but for the rest of the world,” said Don Smith, chief operating officer of the United Farmers of Alberta Co-operative.

“The two are very closely linked together… Agriculture requires fuel, and it requires lubricants. It requires heat and electricity. Modern agriculture can’t be done without energy, and it is a significant portion of operating expenses on a farm.”

The need for stable food sources is critical to a global economy whose population is set to reach 9.7 billion people by 2050.

The main pillars of food security are availability and affordability, said Keith Currie, president of the Canadian Federation of Agriculture (CFA).

“In Canada, availability is not so much an issue. We are a very productive country when it comes to agriculture products and food products. But food affordability has become an issue for a number of people,” said Currie, who is also on the advisory council for the advocacy group Energy for a Secure Future.

The average price of food bought in stores increased by nearly 25 per cent over the last five years, according to Statistics Canada.

Restricting access to oil and gas, or policies like carbon taxes that increase the cost for farmers to use these fuels, risk increasing food costs even more for Canadians and making Canadian food exports less attractive to global customers, CFA says.

“Canada is an exporting nation when it comes to food. In order for us to be competitive we not only have to have the right trade deals in place, but we have to be competitive price wise too,” Currie said.

Under an incredible Saskatchewan sky, a farmer walks toward his air seeder to begin the process of planting this year’s crop. Getty Images photo

Canada is the fifth-largest exporter of agri-food and seafood in the world, exporting approximately $93 billion of products in 2022, according to Agriculture Canada.

Meanwhile, Canadians spent nearly $190 billion on food, beverage, tobacco and cannabis products in 2022, representing the third-largest household expenditure category after transportation and shelter.

Currie said there are opportunities for renewable energy to help supplement oil and gas in agriculture, particularly in biofuels.

“But we’re not at a point from a production standpoint or an overall infrastructure standpoint where it’s a go-to right away,” he said.

“We need the infrastructure and we need probably a lot of incentives before we can even think about moving away from the oil and gas sector as a supplier of energy right now.”

Worldwide demand for oil and gas in the agriculture sector continues to grow, according to CEC Research.

Driven by Africa and Latin America, global oil use in agriculture increased to 118 million tonnes of oil equivalent (Mtoe) in 2022, up from 110 million tonnes in 1990.

Demand for natural gas also increased — from 7.5 Mtoe in 1990 to 11 Mtoe in 2022.

Sylvain Charlebois, senior director, in the Agri-Food Analytics Lab at Dalhousie University, said food security depends on three pillars – access, safety, and affordability.

“Countries are food secure on different levels. Canada’s situation I think is envious to be honest. I think we’re doing very well compared to other countries, especially when it comes to safety and access,” said Charlebois.

“If you have a food insecure population, civil unrest is more likely, tensions, and political instability in different regions become more of a possibility.”

As a country, access to affordable energy is key as well, he said.

“The food industry highly depends on energy sources and of course food is energy. More and more we’re seeing a convergence of the two worlds – food and energy… It forces the food sector to play a much larger role in the energy agenda of a country like Canada.”

Agriculture

Canada’s air quality among the best in the world

From the Fraser Institute

By Annika Segelhorst and Elmira Aliakbari

Canadians care about the environment and breathing clean air. In 2023, the share of Canadians concerned about the state of outdoor air quality was 7 in 10, according to survey results from Abacus Data. Yet Canada outperforms most comparable high-income countries on air quality, suggesting a gap between public perception and empirical reality. Overall, Canada ranks 8th for air quality among 31 high-income countries, according to our recent study published by the Fraser Institute.

A key determinant of air quality is the presence of tiny solid particles and liquid droplets floating in the air, known as particulates. The smallest of these particles, known as fine particulate matter, are especially hazardous, as they can penetrate deep into a person’s lungs, enter the blood stream and harm our health.

Exposure to fine particulate matter stems from both natural and human sources. Natural events such as wildfires, dust storms and volcanic eruptions can release particles into the air that can travel thousands of kilometres. Other sources of particulate pollution originate from human activities such as the combustion of fossil fuels in automobiles and during industrial processes.

The World Health Organization (WHO) and the Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment (CCME) publish air quality guidelines related to health, which we used to measure and rank 31 high-income countries on air quality.

Using data from 2022 (the latest year of consistently available data), our study assessed air quality based on three measures related to particulate pollution: (1) average exposure, (2) share of the population at risk, and (3) estimated health impacts.

The first measure, average exposure, reflects the average level of outdoor particle pollution people are exposed to over a year. Among 31 high-income countries, Canadians had the 5th-lowest average exposure to particulate pollution.

Next, the study considered the proportion of each country’s population that experienced an annual average level of fine particle pollution greater than the WHO’s air quality guideline. Only 2 per cent of Canadians were exposed to fine particle pollution levels exceeding the WHO guideline for annual exposure, ranking 9th of 31 countries. In other words, 98 per cent of Canadians were not exposed to fine particulate pollution levels exceeding health guidelines.

Finally, the study reviewed estimates of illness and mortality associated with fine particle pollution in each country. Canada had the fifth-lowest estimated death and illness burden due to fine particle pollution.

Taken together, the results show that Canada stands out as a global leader on clean air, ranking 8th overall for air quality among high-income countries.

Canada’s record underscores both the progress made in achieving cleaner air and the quality of life our clean air supports.

Agriculture

Growing Alberta’s fresh food future

A new program funded by the Sustainable Canadian Agricultural Partnership will accelerate expansion in Alberta greenhouses and vertical farms.

Albertans want to keep their hard-earned money in the province and support producers by choosing locally grown, high-quality produce. The new three-year, $10-milllion Growing Greenhouses program aims to stimulate industry growth and provide fresh fruit and vegetables to Albertans throughout the year.

“Everything our ministry does is about ensuring Albertans have secure access to safe, high-quality food. We are continually working to build resilience and sustainability into our food production systems, increase opportunities for producers and processors, create jobs and feed Albertans. This new program will fund technologies that increase food production and improve energy efficiency.”

“Through this investment, we’re supporting Alberta’s growers and ensuring Canadians have access to fresh, locally-grown fruits and vegetables on grocery shelves year-round. This program strengthens local communities, drives innovation, and creates new opportunities for agricultural entrepreneurs, reinforcing Canada’s food system and economy.”

The Growing Greenhouses program supports the controlled environment agriculture sector with new construction or expansion improvements to existing greenhouses and vertical farms that produce food at a commercial scale. It also aligns with Alberta’s Buy Local initiative launched this year as consumers will be able to purchase more local produce all year-round.

The program was created in alignment with the needs identified by the greenhouse sector, with a goal to reduce seasonal import reliance entering fall, which increases fruit and vegetable prices.

“This program is a game-changer for Alberta’s greenhouse sector. By investing in expansion and innovation, we can grow more fresh produce year-round, reduce reliance on imports, and strengthen food security for Albertans. Our growers are ready to meet the demand with sustainable, locally grown vegetables and fruits, and this support ensures we can do so while creating new jobs and opportunities in communities across the province. We are very grateful to the Governments of Canada and Alberta for this investment in our sector and for working collaboratively with us.”

Sustainable Canadian Agricultural Partnership (Sustainable CAP)

Sustainable CAP is a five-year, $3.5-billion investment by federal, provincial and territorial governments to strengthen competitiveness, innovation and resiliency in Canada’s agriculture, agri-food and agri-based products sector. This includes $1 billion in federal programs and activities and $2.5 billion that is cost-shared 60 per cent federally and 40 per cent provincially/territorially for programs that are designed and delivered by provinces and territories.

Quick facts

- Alberta’s greenhouse sector ranks fourth in Canada:

- 195 greenhouses produce $145 million in produce and 60 per cent of them operate year-round.

- Greenhouse food production is growing by 6.2 per cent annually.

- Alberta imports $349 million in fresh produce annually.

- The program supports sector growth by investing in renewable and efficient energy systems, advanced lighting systems, energy-saving construction, and automation and robotics systems.

Related information

-

Bruce Dowbiggin1 day ago

Bruce Dowbiggin1 day agoWayne Gretzky’s Terrible, Awful Week.. And Soccer/ Football.

-

espionage14 hours ago

espionage14 hours agoWestern Campuses Help Build China’s Digital Dragnet With U.S. Tax Funds, Study Warns

-

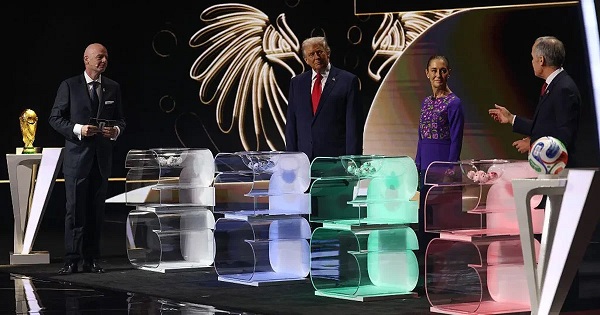

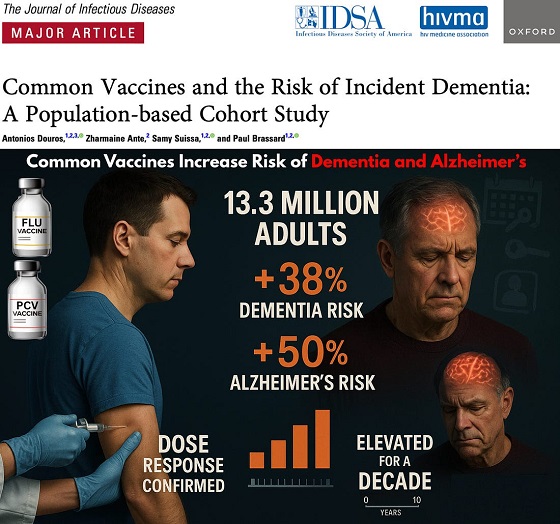

Focal Points5 hours ago

Focal Points5 hours agoCommon Vaccines Linked to 38-50% Increased Risk of Dementia and Alzheimer’s

-

Opinion23 hours ago

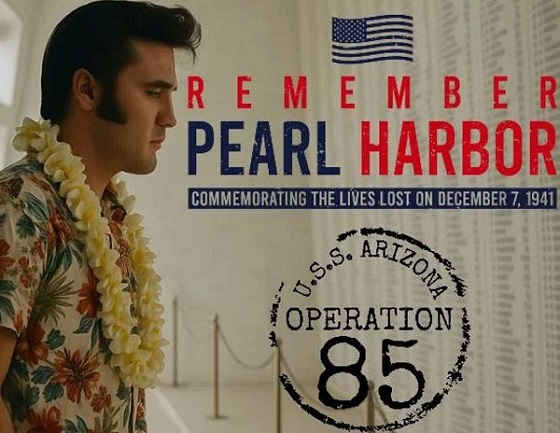

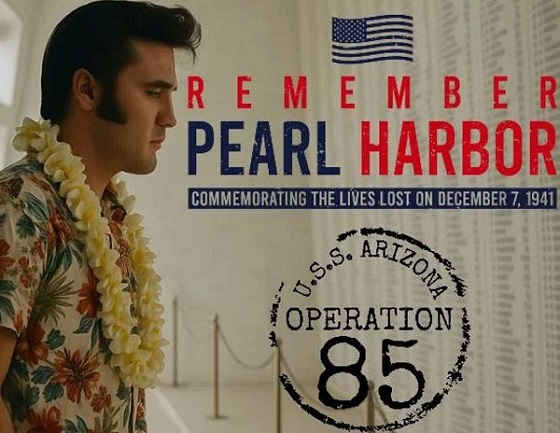

Opinion23 hours agoThe day the ‘King of rock ‘n’ roll saved the Arizona memorial

-

Agriculture24 hours ago

Agriculture24 hours agoCanada’s air quality among the best in the world

-

Business12 hours ago

Business12 hours agoCanada invests $34 million in Chinese drones now considered to be ‘high security risks’

-

Economy13 hours ago

Economy13 hours agoAffordable housing out of reach everywhere in Canada

-

Health3 hours ago

Health3 hours agoThe Data That Doesn’t Exist