C2C Journal

How Canada Lost its Way on Freedom of Speech

By Josh Dehaas

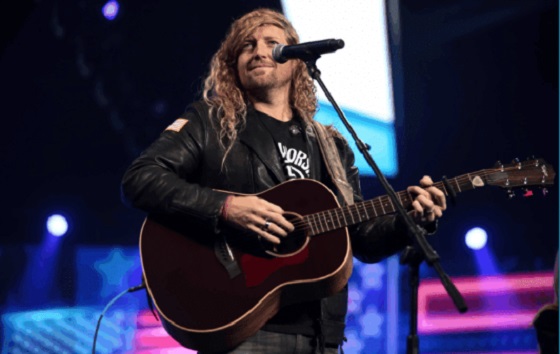

American singer Sean Feucht has completed his 11-city tour of Canada. Well, sort of anyway. Public officials cancelled or denied him permits in nine cities, from Halifax to Abbotsford, B.C. Montreal went so far as to fine a church $2,500 for hosting his concert. As you know by now, these shows were cancelled because some people are offended by Feucht’s viewpoints, such as his claim that LGBT Pride is a “demonic agenda seeking to destroy our culture and pervert our children.”

How can a country that purports to protect freedom of speech tolerate this blatant censorship? The answer is that our free speech law is so difficult to decipher that some officials may have genuinely believed they can shut Feucht down to prevent hateful or discriminatory speech.

As I explain in a new essay for C2C Journal, the problem is that, since the advent of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms in 1982, the Supreme Court has failed to draw a principled line between when governments can and can’t limit expression. This is despite the fact that a principled rule – first articulated by John Stuart Mill in his still-famous 1864 essay On Liberty and established to varying degrees in Canada’s pre-Charter jurisprudence – was ripe for the taking.

Mill argued – persuasively, in my opinion – that governments can limit harmful forms of expression like nuisance noise or imminent physical consequences like inciting an angry mob to burn down a person’s house – but they must never seek to censor content or ideas. A clear, principled line, understandable to every citizen, government official and judge. Something like “golden rule” for understanding the domain, and legitimate boundaries, of free speech.

Canada’s high court failed, however, to recognize this golden rule in the first big post-Charter free speech case brought before it, 1989’s Irwin Toy. There, Chief Justice Brian Dickson stated correctly that “freedom of expression was entrenched in our Constitution so as to ensure that everyone can manifest their thoughts, opinions, beliefs, indeed all expressions of the heart and mind, however unpopular, distasteful or contrary to the mainstream.”

But then Dickson lost the plot, stating that all expression except physical violence – even parking a car illegally in protest – is protected. While such an act is expressive, there’s no reason to suggest that it is protected expression. Enforcing a law against parking illegally is not targeting the content of speech; it’s targeting a harmful form. But Dickson insisted upon writing that any attempt to convey meaning is initially Charter-protected.

Instead of providing clarity, however, Dickson’s lack of a principled distinction triggered ever-more Charter-related litigation. All speech cases now end up being decided under something called the “Oakes test”. It allows governments to limit Charter rights if they can convince a judge that the benefits of their measure are somehow “proportional” to the harms caused to the individual.

That’s what happened in 1990, when Dickson for a 4-3 majority found that Alberta schoolteacher Jim Keegstra could be jailed for what he said about Jewish people. In her lengthy dissent, Justice Beverley McLachlin concluded that the Criminal Code’s hate speech provision was unconstitutional because the provision “strikes directly at…content and at the viewpoints of individuals.” The subjectivity of “hatred”, she also wrote, made it so difficult to define that any prohibition would deter some people from speaking at all. Dickson responded in a decision called Taylor, where he said the words “hatred and contempt” are limited to “unusually strong and deep felt emotions of detestation, calumny and vilification.”

But how can anyone know whether their words count as protected expression or might land them in jail? In 2013, the Supreme Court was forced to try to answer that in Whatcott. In a 6-0 decision, Justice Marshall Rothstein found that speech that betrays mere “dislike,” that “discredits”, “humiliates” or “offends”, is protected, and that people are even free to “debate or speak out against the rights or characteristics of vulnerable groups.” However, the court found that banning hatred remained constitutional.

Again, though, how can you differentiate between speech that “ridicules” and speech that “vilifies” or speech that is “detestation” rather than “dislike”? Rothstein said one must look for the “hallmarks of hatred” such as “blaming [a group’s] members for the current problems in society,” saying they’re “plotting to destroy western civilization,” or equating them with “groups traditionally reviled in society, such as child abusers [or] pedophiles.” In the end, Whatcott didn’t clarify much.

In 2021, the Supreme Court was forced to try again in Ward. A 5-4 majority found that limits on expression are justified in two situations: when the speech meets the definition of “hatred” set out in Whatcott or when it forces people “to argue for their basic humanity or social standing, as a precondition to participating in the deliberative aspects of our democracy.”

Now, picture yourself as a mayor whose constituents are demanding you cancel Feucht. While it seems clear to me that Feucht’s speech does not meet the definition of hatred from Whatcott, some will argue it does. Others will say, citing Ward, that it would “force certain persons to argue for their basic humanity or social standing….” We can’t know for sure what a judge will decide – and that’s the problem. Had the Dickson court recognized Mill’s principle, that ideas must never be censored but that preventing harmful forms or imminent physical consequences of speech can be justifiably limited, it would have been clear to all that the shows must go on.

The original, full-length version of this article was recently published in C2C Journal.

Josh Dehaas is Counsel with the Canadian Constitution Foundation and co-host of the Not Reserving Judgment podcast.

Artificial Intelligence

The Emptiness Inside: Why Large Language Models Can’t Think – and Never Will

This is a special preview article from the:

Early attempts at artificial intelligence (AI) were ridiculed for giving answers that were confident, wrong and often surreal – the intellectual equivalent of asking a drunken parrot to explain Kant. But modern AIs based on large language models (LLMs) are so polished, articulate and eerily competent at generating answers that many people assume they can know and, even

better, can independently reason their way to knowing.

This confidence is misplaced. LLMs like ChatGPT or Grok don’t think. They are supercharged autocomplete engines. You type a prompt; they predict the next word, then the next, based only on patterns in the trillions of words they were trained on. No rules, no logic – just statistical guessing dressed up in conversation. As a result, LLMs have no idea whether a sentence is true or false or even sane; they only “know” whether it sounds like sentences they’ve seen before. That’s why they often confidently make things up: court cases, historical events, or physics explanations that are pure fiction. The AI world calls such outputs

“hallucinations”.

But because the LLM’s speech is fluent, users instinctively project self-understanding onto the model, triggered by the same human “trust circuits” we use for spotting intelligence. But it is fallacious reasoning, a bit like hearing someone speak perfect French and assuming they must also be an excellent judge of wine, fashion and philosophy. We confuse style for substance and

we anthropomorphize the speaker. That in turn tempts us into two mythical narratives: Myth 1: “If we just scale up the models and give them more ‘juice’ then true reasoning will eventually emerge.”

Bigger LLMs do get smoother and more impressive. But their core trick – word prediction – never changes. It’s still mimicry, not understanding. One assumes intelligence will magically emerge from quantity, as though making tires bigger and spinning them faster will eventually make a car fly. But the obstacle is architectural, not scalar: you can make the mimicry more

convincing (make a car jump off a ramp), but you don’t convert a pattern predictor into a truth-seeker by scaling it up. You merely get better camouflage and, studies have shown, even less fidelity to fact.

Myth 2: “Who cares how AI does it? If it yields truth, that’s all that matters. The ultimate arbiter of truth is reality – so cope!”

This one is especially dangerous as it stomps on epistemology wearing concrete boots. It effectively claims that the seeming reliability of LLM’s mundane knowledge should be extended to trusting the opaque methods through which it is obtained. But truth has rules. For example, a conclusion only becomes epistemically trustworthy when reached through either: 1) deductive reasoning (conclusions that must be true if the premises are true); or 2) empirical verification (observations of the real world that confirm or disconfirm claims).

LLMs do neither of these. They cannot deduce because their architecture doesn’t implement logical inference. They don’t manipulate premises and reach conclusions, and they are clueless about causality. They also cannot empirically verify anything because they have no access to reality: they can’t check weather or observe social interactions.

Attempting to overcome these structural obstacles, AI developers bolt external tools like calculators, databases and retrieval systems onto an LLM system. Such ostensible truth-seeking mechanisms improve outputs but do not fix the underlying architecture.

The “flying car” salesmen, peddling various accomplishments like IQ test scores, claim that today’s LLMs show superhuman intelligence. In reality, LLM IQ tests violate every rule for conducting intelligence tests, making them a human-prompt engineering skills competition rather than a valid assessment of machine smartness.

Efforts to make LLMs “truth-seeking” by brainwashing them to align with their trainer’s preferences through mechanisms like RLHF miss the point. Those attempts to fix bias only make waves in a structure that cannot support genuine reasoning. This regularly reveals itself through flops like xAI Grok’s MechaHitler bravado or Google Gemini’s representing America’s Founding Fathers as a lineup of “racialized” gentlemen.

Other approaches exist, though, that strive to create an AI architecture enabling authentic thinking:

Symbolic AI: uses explicit logical rules; strong on defined problems, weak on ambiguity;

Causal AI: learns cause-and-effect relationships and can answer “what if” questions;

Neuro-symbolic AI: combines neural prediction with logical reasoning; and

Agentic AI: acts with the goal in mind, receives feedback and improves through trial-and-error.

Unfortunately, the current progress in AI relies almost entirely on scaling LLMs. And the alternative approaches receive far less funding and attention – the good old “follow the money” principle. Meanwhile, the loudest “AI” in the room is just a very expensive parrot.

LLMs, nevertheless, are astonishing achievements of engineering and wonderful tools useful for many tasks. I will have far more on their uses in my next column. The crucial thing for users to remember, though, is that all LLMs are and will always remain linguistic pattern engines, not epistemic agents.

The hype that LLMs are on the brink of “true intelligence” mistakes fluency for thought. Real thinking requires understanding the physical world, persistent memory, reasoning and planning that LLMs handle only primitively or not all – a design fact that is non-controversial among AI insiders. Treat LLMs as useful thought-provoking tools, never as trustworthy sources. And stop waiting for the parrot to start doing philosophy. It never will.

The original, full-length version of this article was recently published as Part I of a two-part series in C2C Journal. Part II can be read here.

Gleb Lisikh is a researcher and IT management professional, and a father of three children, who lives in Vaughan, Ontario and grew up in various parts of the Soviet Union.

C2C Journal

Learning the Truth about “Children’s Graves” and Residential Schools is More Important than Ever

This is a special preview article from the:

By Tom Flanagan

When the book Grave Error was published by True North in late 2023, it became an instant best-seller. People wanted to read the book because it contained well-documented information not readily available elsewhere concerning the history of Canada’s Indian Residential Schools (IRS) and the facts surrounding recent claims about “unmarked graves.”

Dead Wrong: How Canada Got the Residential School Story So Wrong is the just-published sequel to Grave Error. Edited by Chris Champion and me, with chapters written by knowledgeable academics, journalists, researchers and even several contributors who once worked directly in residential schools or dedicated Indian hospitals, Dead Wrong was published because the struggle for accurate information on this contentious subject continues. Let me share with you a little of what’s in Dead Wrong.

Outrageously, the New York Times, the world’s most influential newspaper among liberals and “progressives”, has never retracted its outrageously false headline that “mass graves” were uncovered at Kamloops in 2021. Journalist Jonathan Kay exposes that scandal.

With similarly warped judgment, the legacy media were enthused about last year’s so-called documentary Sugarcane, a feature-length film sponsored by National Geographic and nominated for an Academy Award. The only reporter to spot Sugarcane’s dozens of egregious factual errors was independent journalist Michelle Stirling; her expose is included in Dead Wrong.

In spring 2024, the small Interior B.C. city of Quesnel made national news when the mayor’s wife bought ten copies of Grave Error for distribution to friends. After noisy protests by people who had never read the book, Quesnel city council voted to censure Mayor Ron Paull and tried to force him from office. It’s all described in Dead Wrong.

Also not to be forgotten is how the Law Society of B.C. has forced upon its members training materials that assert against all evidence that children’s remains have been discovered at Kamloops. As told by James Pew, B.C. MLA Dallas Brodie was expelled not from the NDP but from the Conservative caucus for daring to point out this obvious and incontrovertible

falsehood. But the facts are that ground-penetrating radar (used at the former Kamloops IRS) can detect only “anomalies” or “disturbances”, not identify what those might be; that no excavations have been carried out; and that no human remains whatsoever, let alone “215 children’s bodies”, have been found there. Brodie is completely correct.

Then there is the story of Jim McMurtry, suspended by the Abbotsford District School Board shortly after the May 2021 Kamloops announcement. McMurtry’s offence was to tell students the truth that, while some Indigenous students did die in residential schools, the main cause was tuberculosis. His own book The Scarlet Lesson is excerpted in Dead Wrong.

Historian Ian Gentles and former IRS teacher Pim Wiebel offer a richly detailed analysis of health and medical conditions in the schools. They show that these were much better than what prevailed in the Indian reserves from which most students came.

Another important contribution to understanding the medical issues is by Dr. Eric Schloss, narrating the history of the Charles Camsell Indian Hospital in Edmonton. IRS facilities usually included small clinics, but students with serious problems were often transferred to Indian Hospitals for more intensive care. Schloss, who worked in the Camsell, describes how it delivered state-of-the-art medicine, probably better than the care available to most non-native children anywhere in Canada at the time.

Rodney Clifton’s contribution, “They would call me a ‘Denier,’” describes his personal experiences working in two IRS in the 1960s. Clifton does not tell stories of hunger, brutal punishment and suppression of Indigenous culture, but of games, laughter and trying to learn native languages from his Indian and Inuit charges.

And far from the IRS system being a deliberate, sustained program of cultural genocide, as Toronto lawyer and historian Greg Piasetzki explains, the historical fact is that “Canada Wanted to Close All Residential Schools in the 1940s. Here’s why it couldn’t.” That’s because for many Aboriginal parents, particularly single parents and/or those with large numbers of children,

residential schools were the best deal available. In addition to schooling their kids, they offered paid employment to large numbers of Indigenous Canadians as cooks, janitors, farmers and health care workers, and later as teachers and even principals.

Another gravely important issue is the recent phenomenon of charging critics with “residential school denialism.” This is a false accusation hurled by true believers in what has become known as the “Kamloops narrative”, aimed at shutting down criticism or questions. A key event in this process was when NDP MP Leah Gazan in 2022 persuaded the House of Commons to approve a

resolution “That, in the opinion of the House this government must recognize what happened in Canada’s Indian residential schools as genocide.”

In 2024, Gazan took the next step by introducing a private member’s bill to criminalize dissent about the IRS system. Remember, the slur of “denialist” is a term drawn from earlier debates about the Holocaust. Gazan’s bill failed to pass, but she reintroduced it in 2025. Had such provisions been in force back in 2021, it might well have become a crime to point out that the

Kamloops GPR survey had identified soil anomalies, not buried bodies. Frances Widdowson examines this sordid political campaign of denunciation.

As the proponents of the Kamloops narrative fail to provide convincing hard evidence for it, they hope to mobilize the authority of the state to stamp out dissent. One of the main goals behind publication of Dead Wrong is to head off this drive toward authoritarianism.

Happily, Dead Wrong is already an Amazon best-seller based on pre-publication orders. The struggle for truth continues.

The original, full-length version of this article was recently published by C2C Journal.

Tom Flanagan is the author of many books on Indigenous history and policy, including (with C.P. Champion) the best-selling Grave Error: How the Media Misled Us and the Truth about Residential Schools.

-

MAiD2 days ago

MAiD2 days agoFrom Exception to Routine. Why Canada’s State-Assisted Suicide Regime Demands a Human-Rights Review

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoCarney government should privatize airports—then open airline industry to competition

-

Alberta2 days ago

Alberta2 days agoCarney’s pipeline deal hits a wall in B.C.

-

Alberta1 day ago

Alberta1 day agoAlberta Sports Hall of Fame Announces Class of 2026 Inductees

-

Censorship Industrial Complex1 day ago

Censorship Industrial Complex1 day agoConservative MP Leslyn Lewis slams Liberal plan targeting religious exemption in hate speech bil

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoWhat’s Going On With Global Affairs Canada and Their $392 Million Spending Trip to Brazil?

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoIs Carney Falling Into The Same Fiscal Traps As Trudeau?

-

Energy1 day ago

Energy1 day agoCanada following Europe’s stumble by ignoring energy reality