armed forces

From Batoche to Kandahar: Canada’s Sacrifices for Peace

From the Frontier Centre for Public Policy

By Gerry Bowler

There is a grave on a riverbank near Batoche, Saskatchewan. It contains the remains of a soldier from Ontario who died in 1885 under General Middleton during the last battle of the Northwest Rebellion. It has been tended for almost 150 years by the Métis families whose ancestors had fought against him. His name was Gunner William Phillips and he was 19 years old.

Up a dirt road in the Boshof District of Free State, South Africa is a memorial garden in which are buried the 34 bodies of Canadians killed at the Battle of Paardeberg in 1900. They fell driving a Boer kommando off the heights where they had been dug in and inflicting severe casualties on the British forces below. Private Zachary Richard Edmond Lewis of the Royal Canadian Regiment lies there. He was the son of Millicent Lewis and was 27 years old.

On April 22, 1915 the German army launched its first poison gas attack on Allied trenches near Ypres, Belgium during the First World War. When French troops on their flanks broke and ran, the 1st Canadian Division stood fast amid the chlorine cloud and repelled their attackers, suffering 2,000 casualties in the process. On the grave of Private Arthur Ernest Williams of the 8th Battalion are the words “Remember, He Who Yields His Life is a Soldier and a Man.” Private Williams was 16 years old.

When the Japanese invaded Hong Kong in December 1941, Canadian troops from the Winnipeg Grenadiers were there to resist them. Among them was Sergeant-Major J.R. Osborn whose men were surrounded and subject to grenade attacks. Osborn caught several of these and flung them back but when one could not be retrieved in time he threw himself on the grenade as it exploded trying to save his men. His body was never found after the battle but his name is inscribed on a monument in Sai Wan Bay War Cemetery.

In the hills south of Algiers is Dely Ibrahim Cemetery. This is where they buried the body of RCAF Pilot Officer John Michael Quinlan after the crash of his Wellington bomber in March, 1944. He was a movie-star handsome student from Prince Albert, Saskatchewan and my father’s best friend in the squadron. I carry his family name as my middle name as does my little grand-daughter.

The Kandahar Cenotaph in the Afghanistan Memorial Hall at National Defence Headquarters in Ottawa honours those Canadians who died fighting Islamic terrorists. 158 stones are bearing the faces of the soldiers who were repatriated from where they fell and now are buried in graves in their home communities across the country. One of those stones commemorates Warrant Officer Gaétan Joseph Francis Maxime Roberge of the Royal 22nd Regiment who is buried in a cemetery in Sudbury. He was 45 when he was killed by a bomb. He left behind a wife, an 11-year-old daughter and twin 6-year-old girls.

On November 11, we pause to remember the 118,000 Canadian men and women who died fighting, among others, Fenian invaders, Islamic jihadis in Sudan, the armies of Kaiser Wilhelm, Benito Mussolini, and Imperial Japan, Nazi SS Panzer regiments, Chinese and North Korean forces, ethnic warlords in the Balkans, and the Taliban. They died in North Atlantic convoys, in French trenches, in primitive field hospitals, on beaches in Normandy, in the air over England, on frozen hills in Korea, in jungle POW camps, on peace-keeping duty in Cyprus, in the Medak Pocket in Croatia, and in the mountain passes of Afghanistan. We also remember the hundreds of thousands more who returned home alive, but mutilated, shattered in body and mind, the families deprived of sons, fathers, and brothers, and the communities who lost teachers, hockey players, volunteers, pastors, nurses, and neighbours.

We remember them because in honouring their memory we honour the values on which Canada was built. They did not die to create a Canadian empire, acquire foreign territory or satisfy some ruler’s grandiosity; they fought and suffered to protect parliamentary democracy, freedom of expression and religion, a tolerant society, and the right to live in peace.

On November 11, let us be clear that the prosperity and tranquility enjoyed today by North Americans, Europeans, South Koreans, Japanese, Indians, Malaysians, Singaporeans, Filipinos, etc., etc., were purchased with the blood of heavily-armed men in military uniform, many of them with maple leaf patches on their shoulders. A country which is contemptuous towards its duty to maintain its armed forces, where schools forbid personnel in service dress from attending remembrance assemblies lest their presence makes children and parents “feel unsafe,” or where Forces chaplains are instructed to avoid religious language or symbols in services commemorating our dead, is a nation lost to its memories and unlikely to have much of a future.

KILLED IN ACTION. BELOVED DAUGHTER OF ANGUS & MARY MAUD MACDONALD,

Nursing Sister Katherine MacDonald, Canadian Army Nursing Service, May 19th 1918

HE WOULD GIVE HIS DINNER TO A HUNGRY DOG AND GO WITHOUT HIMSELF.

Gunner Charles Douglas Moore, Canadian Anti-Aircraft Battery, September 19th 1917

BREAK, DAY OF GOD, SWEET DAY OF PEACE, AND BID THE SHOUT OF WARRIORS CEASE.

Sergeant Wellesley Seymour Taylor, 14th Battalion, May 1st 1916

Gerry Bowler, historian, is a Senior Fellow at the Frontier Centre for Public Policy

armed forces

Global Military Industrial Complex Has Never Had It So Good, New Report Finds

From the Daily Caller News Foundation

The global war business scored record revenues in 2024 amid multiple protracted proxy conflicts across the world, according to a new industry analysis released on Monday.

The top 100 arms manufacturers in the world raked in $679 billion in revenue in 2024, up 5.9% from the year prior, according to a new Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) study. The figure marks the highest ever revenue for manufacturers recorded by SIPRI as the group credits major conflicts for supplying the large appetite for arms around the world.

“The rise in the total arms revenues of the Top 100 in 2024 was mostly due to overall increases in the arms revenues of companies based in Europe and the United States,” SIPRI said in their report. “There were year-on-year increases in all the geographical areas covered by the ranking apart from Asia and Oceania, which saw a slight decrease, largely as a result of a notable drop in the total arms revenues of Chinese companies.”

Notably, Chinese arms manufacturers saw a large drop in reported revenues, declining 10% from 2023 to 2024, according to SIPRI. Just off China’s shores, Japan’s arms industry saw the largest single year-over-year increase in revenue of all regions measured, jumping 40% from 2023 to 2024.

American companies dominate the top of the list, which measures individual companies’ revenue, with Lockheed Martin taking the top spot with $64,650,000,000 of arms revenue in 2024, according to the report. Raytheon Technologies, Northrop Grumman and BAE Systems follow shortly after in revenue,

The Czechoslovak Group recorded the single largest jump in year-on-year revenue from 2023 to 2024, increasing its haul by 193%, according to SIPRI. The increase is largely driven by their crucial role in supplying arms and ammunition to Ukraine.

The Pentagon contracted one of the group’s subsidiaries in August to build a new ammo plant in the U.S. to replenish artillery shell stockpiles drained by U.S. aid to Ukraine.

“In 2024 the growing demand for military equipment around the world, primarily linked to rising geopolitical tensions, accelerated the increase in total Top 100 arms revenues seen in 2023,” the report reads. “More than three quarters of companies in the Top 100 (77 companies) increased their arms revenues in 2024, with 42 reporting at least double-digit percentage growth.”

armed forces

2025 Federal Budget: Veterans Are Bleeding for This Budget

How the 2025 Federal Budget Demands More From Those Who’ve Already Given Everything

I’ve lived the word sacrifice.

Not the political kind that comes in speeches and press releases the real kind. The kind Mark Carney wouldn’t know if it slapped him in the face. The kind that costs sleep, sanity, blood. I’ve watched friends trade comfort for duty, and I’ve watched some of them leave in body bags while the rest of us carried the weight of their absence. So when the Prime Minister stood up this year and told Canadians the new budget would “require sacrifice,” I felt that familiar tightening in the gut the one every veteran knows. You brace for impact. You hope the pain lands in a place that makes sense.

It didn’t.

Kelsi Sheren is a reader-supported publication.

To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Six months into Mark Carney’s limp imitation of leadership, it’s painfully clear who’s actually paying the bill. The 2025 budget somehow managing to bleed the country dry while still projecting a $78-billion deficit shields the political class, funnels money toward his network of insiders, and then quietly hacks away at the one department that should be sacrosanct: Veterans Affairs Canada.

If there’s one group that’s earned the right to be spared from government-imposed scarcity, it’s the people who carried this country’s flag into danger. Veterans don’t “symbolize” sacrifice they embody it on the daily And when Ottawa tightens the belt on VAC, the consequences aren’t abstract. They’re brutal and direct, causing nothing but more death and destruction. But Mark Carney doesn’t lose sleep over veterans killing themselves.

Punishment disguised as budgeting for a veteran means the difference between keeping a roof or sleeping in a truck. Punishment disguised as budgeting means PTSD left untreated until it turns a human being into another suicide statistic. Punishment disguised as budgeting means a veteran choosing between groceries and medication because some number-shuffler in Ottawa wants to pretend they’re being “responsible.”

This isn’t fiscal restraint it’s political betrayal wrapped in government stationery. Ottawa sells it as hard choices, but the hardness always falls on the backs of the same people: the ones who already paid more than their share, the ones who can’t afford another hit. Carney and his cabinet won’t feel a thing. Not one missed meal. Not one sleepless night. Not one flashback.

But the men and women who already paid in flesh? They’re the ones being told to give more.

That’s not sacrifice.

That’s abandonment dressed up as fiscal policy.

And Canadians need to recognize it for what it is a government that demands loyalty while refusing to give any in return. The fine print in the government’s own documents reveals what the slogans won’t.

Over the next two years, VAC plans to cut $2.227 billion from its “Benefits, Services and Support” programs. [2] Broader “savings initiatives” reach $4.4 billion over four years, much of it through reductions to the medical-cannabis program that thousands of veterans rely on to manage chronic pain and PTSD. [3] Independent analysts estimate yearly losses of roughly $900 million once the cuts are fully implemented. [4]

To put that in perspective: no other department is seeing reductions on this scale. Not Defence, not Infrastructure, not the Prime Minister’s Office thats for damn sure. Only the people who’ve already paid their debt to this country are being asked to give again.

The government’s line is tidy: “We’re not cutting services we’re modernizing. Artificial Intelligence will streamline processing and improve efficiency.”

That sounds fine until you read the departmental notes. The “modernization” translates into fewer human case managers, longer waits, and narrower eligibility. It’s austerity dressed up as innovation. I’ve coached veterans through the system. They don’t need algorithms; they need advocates who understand trauma, identity loss, and the grind of reintegration. They need empathy, not automation.

This isn’t abstract accounting. Behind every dollar is a life on the edge, the human cost and toll is very real.

- Homelessness: Veterans make up a disproportionate number of Canada’s homeless population. Cutting benefits only deepens that crisis.

- Mental Health: Parliament’s ongoing study on veteran suicide shows rising rates of despair linked to delays and denials in VAC services. [5] Knowing MAID for mental illness alone in 2027 will take out a significant amount of us.

- Food Insecurity: A 2024 VAC survey found nearly one in four veterans reported struggling to afford basic groceries. That’s before these cuts.

We talk about “service” like it ends with deployment. It doesn’t. Service continues in how a nation cares for those who carried its battles, and this doesn’t include the cannabis cut to medication or the fight’s we have to fight when they tell us our injuries are “not service related”

The insult is magnified by the timing. These cuts were announced just days before November 11 Remembrance Day, when Canadians bow their heads and say, “We will remember them.”

Apparently, the government remembered to draft the talking points but forgot the meaning behind them, not a single one of the liberal government should have been allowed to show their faces to veteran’s or at a ceremony. They’re nothing but liars, grifters and traitors to this nation. Yes I’m talking about Jill McKnight and Mark Carney.

The budget still runs the second-largest deficit in Canadian history. [6]

Veteran cuts don’t fix that. They barely dent it. What they do is let the government say it’s “finding efficiencies” while avoiding the real structural overspending that created the problem in the first place. When a government chooses to protect its pet projects and insider contracts while pulling support from veterans, that’s not fiscal discipline it’s moral cowardice. The worst part is that This isn’t an isolated move. It fits a six-month pattern: large, attention-grabbing announcements about “reform,” followed by fine print that concentrates power and shifts burden downward. Veterans just happen to be the first visible casualty.

The same budget expands spending in other politically convenient areas green-transition subsidies, digital-governance infrastructure, and administration while the people who once embodied service are told to tighten their belts.

As a combat veteran, I know what it’s like to come home and realize that the fight didn’t end overseas it just changed terrain. We fought for freedom abroad only to watch bureaucratic neglect wage a quieter war here at home. Veterans don’t ask for privilege. They ask for respect, for competence, for follow-through on the promises this country made when it sent them into harm’s way.

Here’s what really needs to change, the liberal government has to go, thats step one. Restore VAC funding immediately. Any “savings” plan that touches benefits, services, or support should be scrapped. End the AI façade. Efficiency can’t replace empathy. Keep human case workers who understand the veteran experience. Audit and transparency. Publish a detailed breakdown of where VAC funds are cut and who approved it. Canadians deserve to see the receipts. National accountability. Every MP who voted for this budget should face veterans in their constituency and explain it, face-to-face.

Budgets are moral documents. They show what a country values. By slashing VAC while running record deficits, this government declared that veterans are expendable line items, not national obligations. The Prime Minister promised “shared sacrifice.” But the only people truly sacrificing are the ones who already gave more than most Canadians ever will.

Sacrifice isn’t about spreadsheets; it’s about service. It’s what every veteran understood when they raised their right hand. This government’s brand of sacrifice asking wounded soldiers to pay for political mismanagement isn’t austerity. It’s abandonment.

Canada owes its veterans more than a wreath once a year. It owes them respect written into every budget, not erased from it.

KELSI SHEREN

Footnotes

[1] The Guardian, “Canada’s 2025 Federal Budget Adds Tens of Billions to Deficit as Carney Spends to Dampen Tariffs Effect,” Nov 5 2025.

[2] True North Wire, “Liberal Budget to Cut $4.23 Billion from Veterans Affairs,” Nov 2025.

[3] StratCann, “Budget 2025 Includes Goal of Saving $4.4 Billion in Medical Cannabis Benefits,” Nov 2025.

[4] Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, “Where Will the Federal Government Cut to Pay for Military Spending and Tax Cuts?” Nov 2025.

[5] House of Commons Standing Committee on Veterans Affairs, “Study on Veteran Suicide and Sanctuary Trauma,” ongoing 2025.

[6] CBC News, “Federal Budget 2025 Deficit Second Largest in Canadian History,” Nov 2025.

Kelsi Sheren is a reader-supported publication.

To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

-

Bruce Dowbiggin1 day ago

Bruce Dowbiggin1 day agoIntegration Or Indignation: Whose Strategy Worked Best Against Trump?

-

COVID-191 day ago

COVID-191 day agoUniversity of Colorado will pay $10 million to staff, students for trying to force them to take COVID shots

-

Banks2 days ago

Banks2 days agoTo increase competition in Canadian banking, mandate and mindset of bank regulators must change

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoLoblaws Owes Canadians Up to $500 Million in “Secret” Bread Cash

-

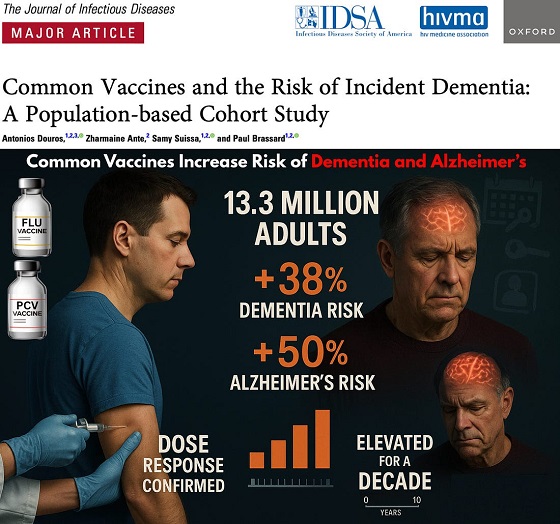

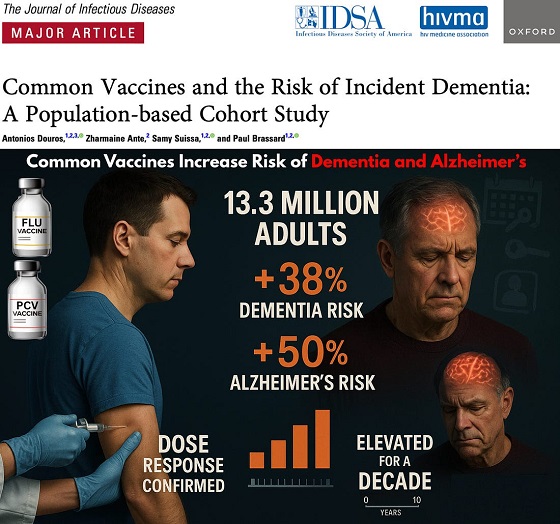

Focal Points2 days ago

Focal Points2 days agoCommon Vaccines Linked to 38-50% Increased Risk of Dementia and Alzheimer’s

-

espionage1 day ago

espionage1 day agoWestern Campuses Help Build China’s Digital Dragnet With U.S. Tax Funds, Study Warns

-

Bruce Dowbiggin1 day ago

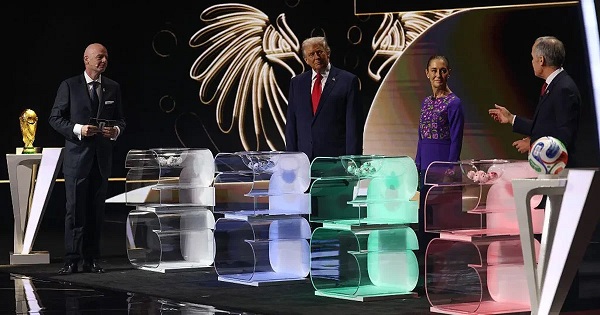

Bruce Dowbiggin1 day agoWayne Gretzky’s Terrible, Awful Week.. And Soccer/ Football.

-

Opinion2 days ago

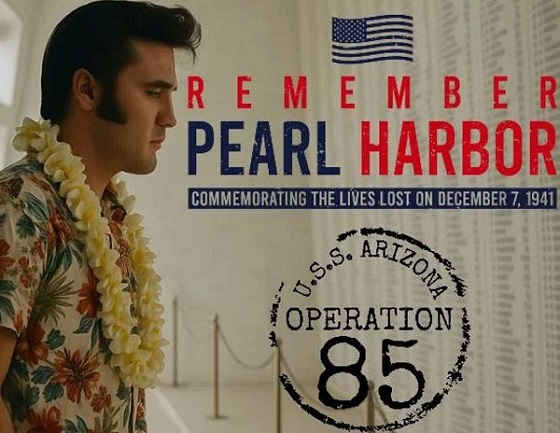

Opinion2 days agoThe day the ‘King of rock ‘n’ roll saved the Arizona memorial