Alberta

Fortis et Liber: Alberta’s Future in the Canadian Federation

From the C2C Journal

By Barry Cooper, professor of political science, University of Calgary

Canada’s western lands, wrote one prominent academic, became provinces “in the Roman sense” – acquired possessions that, once vanquished, were there to be exploited. Laurentian Canada regarded the hinterlands as existing primarily to serve the interests of the heartland. And the current holders of office in Ottawa often behave as if the Constitution’s federal-provincial distribution of powers is at best advisory, if it needs to be acknowledged at all. Reviewing this history, Barry Cooper places Alberta’s widely criticized Sovereignty Act in the context of the Prairie provinces’ long struggle for due constitutional recognition and the political equality of their citizens. Canada is a federation, notes Cooper. Provinces do have rights. Constitutions do mean something. And when they are no longer working, they can be changed.

Alberta

Alberta project would be “the biggest carbon capture and storage project in the world”

Pathways Alliance CEO Kendall Dilling is interviewed at the World Petroleum Congress in Calgary, Monday, Sept. 18, 2023.THE CANADIAN PRESS/Jeff McIntosh

From Resource Works

Carbon capture gives biggest bang for carbon tax buck CCS much cheaper than fuel switching: report

Canada’s climate change strategy is now joined at the hip to a pipeline. Two pipelines, actually — one for oil, one for carbon dioxide.

The MOU signed between Ottawa and Alberta two weeks ago ties a new oil pipeline to the Pathways Alliance, which includes what has been billed as the largest carbon capture proposal in the world.

One cannot proceed without the other. It’s quite possible neither will proceed.

The timing for multi-billion dollar carbon capture projects in general may be off, given the retreat we are now seeing from industry and government on decarbonization, especially in the U.S., our biggest energy customer and competitor.

But if the public, industry and our governments still think getting Canada’s GHG emissions down is a priority, decarbonizing Alberta oil, gas and heavy industry through CCS promises to be the most cost-effective technology approach.

New modelling by Clean Prosperity, a climate policy organization, finds large-scale carbon capture gets the biggest bang for the carbon tax buck.

Which makes sense. If oil and gas production in Alberta is Canada’s single largest emitter of CO2 and methane, it stands to reason that methane abatement and sequestering CO2 from oil and gas production is where the biggest gains are to be had.

A number of CCS projects are already in operation in Alberta, including Shell’s Quest project, which captures about 1 million tonnes of CO2 annually from the Scotford upgrader.

What is CO2 worth?

Clean Prosperity estimates industrial carbon pricing of $130 to $150 per tonne in Alberta and CCS could result in $90 billion in investment and 70 megatons (MT) annually of GHG abatement or sequestration. The lion’s share of that would come from CCS.

To put that in perspective, 70 MT is 10% of Canada’s total GHG emissions (694 MT).

The report cautions that these estimates are “hypothetical” and gives no timelines.

All of the main policy tools recommended by Clean Prosperity to achieve these GHG reductions are contained in the Ottawa-Alberta MOU.

One important policy in the MOU includes enhanced oil recovery (EOR), in which CO2 is injected into older conventional oil wells to increase output. While this increases oil production, it also sequesters large amounts of CO2.

Under Trudeau era policies, EOR was excluded from federal CCS tax credits. The MOU extends credits and other incentives to EOR, which improves the value proposition for carbon capture.

Under the MOU, Alberta agrees to raise its industrial carbon pricing from the current $95 per tonne to a minimum of $130 per tonne under its TIER system (Technology Innovation and Emission Reduction).

The biggest bang for the buck

Using a price of $130 to $150 per tonne, Clean Prosperity looked at two main pathways to GHG reductions: fuel switching in the power sector and CCS.

Fuel switching would involve replacing natural gas power generation with renewables, nuclear power, renewable natural gas or hydrogen.

“We calculated that fuel switching is more expensive,” Brendan Frank, director of policy and strategy for Clean Prosperity, told me.

Achieving the same GHG reductions through fuel switching would require industrial carbon prices of $300 to $1,000 per tonne, Frank said.

Clean Prosperity looked at five big sectoral emitters: oil and gas extraction, chemical manufacturing, pipeline transportation, petroleum refining, and cement manufacturing.

“We find that CCUS represents the largest opportunity for meaningful, cost-effective emissions reductions across five sectors,” the report states.

Fuel switching requires higher carbon prices than CCUS.

Measures like energy efficiency and methane abatement are included in Clean Prosperity’s calculations, but again CCS takes the biggest bite out of Alberta’s GHGs.

“Efficiency and (methane) abatement are a portion of it, but it’s a fairly small slice,” Frank said. “The overwhelming majority of it is in carbon capture.”

From left, Alberta Minister of Energy Marg McCuaig-Boyd, Shell Canada President Lorraine Mitchelmore, CEO of Royal Dutch Shell Ben van Beurden, Marathon Oil Executive Brian Maynard, Shell ER Manager, Stephen Velthuizen, and British High Commissioner to Canada Howard Drake open the valve to the Quest carbon capture and storage facility in Fort Saskatchewan Alta, on Friday November 6, 2015. Quest is designed to capture and safely store more than one million tonnes of CO2 each year an equivalent to the emissions from about 250,000 cars. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Jason Franson

Credit where credit is due

Setting an industrial carbon price is one thing. Putting it into effect through a workable carbon credit market is another.

“A high headline price is meaningless without higher credit prices,” the report states.

“TIER credit prices have declined steadily since 2023 and traded below $20 per tonne as of November 2025. With credit prices this low, the $95 per tonne headline price has a negligible effect on investment decisions and carbon markets will not drive CCUS deployment or fuel switching.”

Clean Prosperity recommends a kind of government-backstopped insurance mechanism guaranteeing carbon credit prices, which could otherwise be vulnerable to political and market vagaries.

Specifically, it recommends carbon contracts for difference (CCfD).

“A straight-forward way to think about it is insurance,” Frank explains.

Carbon credit prices are vulnerable to risks, including “stroke-of-pen risks,” in which governments change or cancel price schedules. There are also market risks.

CCfDs are contractual agreements between the private sector and government that guarantees a specific credit value over a specified time period.

“The private actor basically has insurance that the credits they’ll generate, as a result of making whatever low-carbon investment they’re after, will get a certain amount of revenue,” Frank said. “That certainty is enough to, in our view, unlock a lot of these projects.”

From the perspective of Canadian CCS equipment manufacturers like Vancouver’s Svante, there is one policy piece still missing from the MOU: eligibility for the Clean Technology Manufacturing (CTM) Investment tax credit.

“Carbon capture was left out of that,” said Svante co-founder Brett Henkel said.

Svante recently built a major manufacturing plant in Burnaby for its carbon capture filters and machines, with many of its prospective customers expected to be in the U.S.

The $20 billion Pathways project could be a huge boon for Canadian companies like Svante and Calgary’s Entropy. But there is fear Canadian CCS equipment manufacturers could be shut out of the project.

“If the oil sands companies put out for a bid all this equipment that’s needed, it is highly likely that a lot of that equipment is sourced outside of Canada, because the support for Canadian manufacturing is not there,” Henkel said.

Henkel hopes to see CCS manufacturing added to the eligibility for the CTM investment tax credit.

“To really build this eco-system in Canada and to support the Pathways Alliance project, we need that amendment to happen.”

Resource Works News

Alberta

Alberta Next Panel calls for less Ottawa—and it could pay off

From the Fraser Institute

By Tegan Hill

Last Friday, less than a week before Christmas, the Smith government quietly released the final report from its Alberta Next Panel, which assessed Alberta’s role in Canada. Among other things, the panel recommends that the federal government transfer some of its tax revenue to provincial governments so they can assume more control over the delivery of provincial services. Based on Canada’s experience in the 1990s, this plan could deliver real benefits for Albertans and all Canadians.

Federations such as Canada typically work best when governments stick to their constitutional lanes. Indeed, one of the benefits of being a federalist country is that different levels of government assume responsibility for programs they’re best suited to deliver. For example, it’s logical that the federal government handle national defence, while provincial governments are typically best positioned to understand and address the unique health-care and education needs of their citizens.

But there’s currently a mismatch between the share of taxes the provinces collect and the cost of delivering provincial responsibilities (e.g. health care, education, childcare, and social services). As such, Ottawa uses transfers—including the Canada Health Transfer (CHT)—to financially support the provinces in their areas of responsibility. But these funds come with conditions.

Consider health care. To receive CHT payments from Ottawa, provinces must abide by the Canada Health Act, which effectively prevents the provinces from experimenting with new ways of delivering and financing health care—including policies that are successful in other universal health-care countries. Given Canada’s health-care system is one of the developed world’s most expensive universal systems, yet Canadians face some of the longest wait times for physicians and worst access to medical technology (e.g. MRIs) and hospital beds, these restrictions limit badly needed innovation and hurt patients.

To give the provinces more flexibility, the Alberta Next Panel suggests the federal government shift tax points (and transfer GST) to the provinces to better align provincial revenues with provincial responsibilities while eliminating “strings” attached to such federal transfers. In other words, Ottawa would transfer a portion of its tax revenues from the federal income tax and federal sales tax to the provincial government so they have funds to experiment with what works best for their citizens, without conditions on how that money can be used.

According to the Alberta Next Panel poll, at least in Alberta, a majority of citizens support this type of provincial autonomy in delivering provincial programs—and again, it’s paid off before.

In the 1990s, amid a fiscal crisis (greater in scale, but not dissimilar to the one Ottawa faces today), the federal government reduced welfare and social assistance transfers to the provinces while simultaneously removing most of the “strings” attached to these dollars. These reforms allowed the provinces to introduce work incentives, for example, which would have previously triggered a reduction in federal transfers. The change to federal transfers sparked a wave of reforms as the provinces experimented with new ways to improve their welfare programs, and ultimately led to significant innovation that reduced welfare dependency from a high of 3.1 million in 1994 to a low of 1.6 million in 2008, while also reducing government spending on social assistance.

The Smith government’s Alberta Next Panel wants the federal government to transfer some of its tax revenues to the provinces and reduce restrictions on provincial program delivery. As Canada’s experience in the 1990s shows, this could spur real innovation that ultimately improves services for Albertans and all Canadians.

-

International2 days ago

International2 days agoOttawa is still dodging the China interference threat

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoThere’s No Bias at CBC News, You Say? Well, OK…

-

Automotive2 days ago

Automotive2 days agoCanada’s EV gamble is starting to backfire

-

International2 days ago

International2 days ago2025: The Year The Narrative Changed

-

Energy2 days ago

Energy2 days agoCanada’s debate on energy levelled up in 2025

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoSocialism vs. Capitalism

-

Daily Caller2 days ago

Daily Caller2 days agoIs Ukraine Peace Deal Doomed Before Zelenskyy And Trump Even Meet At Mar-A-Lago?

-

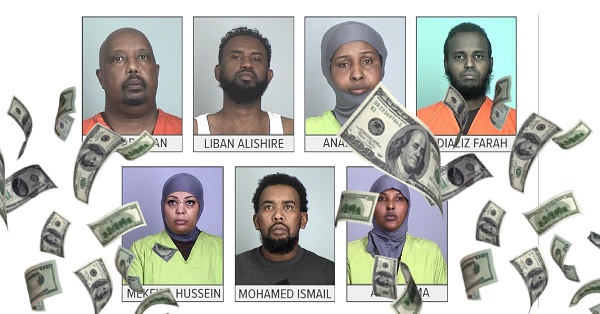

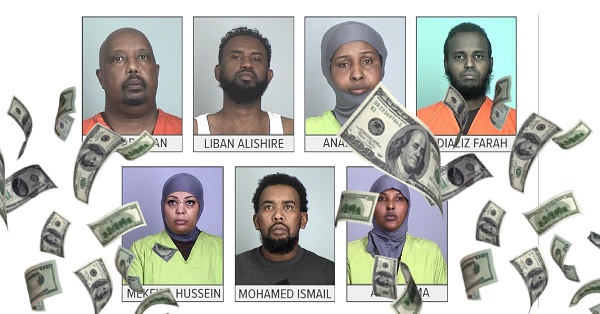

Business1 day ago

Business1 day ago“Magnitude cannot be overstated”: Minnesota aid scam may reach $9 billion

For 200 years Rupert’s Land (its flag shown on top left) along with the Northwest and Northeast Territories were the exclusive commercial domain of the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC), granted by the British Crown; Great Britian officially transferred these vast lands to the Crown in Right of Canada in 1870. (Source of map:

For 200 years Rupert’s Land (its flag shown on top left) along with the Northwest and Northeast Territories were the exclusive commercial domain of the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC), granted by the British Crown; Great Britian officially transferred these vast lands to the Crown in Right of Canada in 1870. (Source of map:  Obscure but legally important: Canada is often said to have “purchased” Rupert’s Land from the Hudson’s Bay Company, but Canada did not actually pay for the land, only for the company’s capital improvements such as Lower Fort Garry in the Rural Municipality of St. Andrews (aka the Stone Fort, top), Fort Edmonton (middle), depicted here after construction of Alberta’s Legislative Assembly building, and the Hudson’s Bay Brigade Trail (bottom). (Sources of images: (top)

Obscure but legally important: Canada is often said to have “purchased” Rupert’s Land from the Hudson’s Bay Company, but Canada did not actually pay for the land, only for the company’s capital improvements such as Lower Fort Garry in the Rural Municipality of St. Andrews (aka the Stone Fort, top), Fort Edmonton (middle), depicted here after construction of Alberta’s Legislative Assembly building, and the Hudson’s Bay Brigade Trail (bottom). (Sources of images: (top)  “Enter the Union on an equal basis with existing states”: In contrast to Canada, the U.S. Northwest Ordinance of 1787 provided a formal and transparent mechanism by which newly settled territories could graduate to statehood if they met certain conditions – gaining the same rights and privileges as the original 13 states.

“Enter the Union on an equal basis with existing states”: In contrast to Canada, the U.S. Northwest Ordinance of 1787 provided a formal and transparent mechanism by which newly settled territories could graduate to statehood if they met certain conditions – gaining the same rights and privileges as the original 13 states. “Our lives our fortunes and our sacred honour”: Métis leaders Louis Riel (top left) and John Bruce (top right) saw the 1870 transfer of Rubert’s Land to Canada as an act of “abandonment” by the British Crown; to protect the interests of the Red River Settlement (bottom), they “refus[ed] to recognise the authority of Canada.” (Sources: (top left photo) Library and Archives Canada, C-018082; (top right photo)

“Our lives our fortunes and our sacred honour”: Métis leaders Louis Riel (top left) and John Bruce (top right) saw the 1870 transfer of Rubert’s Land to Canada as an act of “abandonment” by the British Crown; to protect the interests of the Red River Settlement (bottom), they “refus[ed] to recognise the authority of Canada.” (Sources: (top left photo) Library and Archives Canada, C-018082; (top right photo)  “Provinces in the Roman sense”: According to political scientist James Mallory, Canada’s Prairie provinces were akin to “provinciae” in ancient Rome – conquered lands whose inhabitants were not citizens and who existed to serve the interests of the Imperial Capital and the Italian heartland. Shown, the fall of Macedonia in 168 BC depicted in The Triumph of Aemilius Paulus by Carle Vernet, 1789. (Source of painting:

“Provinces in the Roman sense”: According to political scientist James Mallory, Canada’s Prairie provinces were akin to “provinciae” in ancient Rome – conquered lands whose inhabitants were not citizens and who existed to serve the interests of the Imperial Capital and the Italian heartland. Shown, the fall of Macedonia in 168 BC depicted in The Triumph of Aemilius Paulus by Carle Vernet, 1789. (Source of painting:  In 1905 the Dominion of Canada carved the new provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan out of portions of the Northwest Territories; the newcomers were treated as distinctly second-class in comparison to the original provinces, among other things only gaining full control over their lands and natural resources in 1930. (Sources of photos (clockwise, starting top-left):

In 1905 the Dominion of Canada carved the new provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan out of portions of the Northwest Territories; the newcomers were treated as distinctly second-class in comparison to the original provinces, among other things only gaining full control over their lands and natural resources in 1930. (Sources of photos (clockwise, starting top-left):  The Prairie provinces continued to be subjected to destructive Laurentian policies throughout the 20th century, such as prolongation of the Canadian Wheat Board, official bilingualism and the National Energy Program, implemented by Pierre Trudeau in 1981 (shown on bottom left, to the right of Alberta premier Peter Lougheed in the centre). Depicted on bottom right, oil sands facility at Mildred Lake. (Sources of photos: (top left) Canadian Government Motion Picture Bureau/Library and Archives Canada/C-064834; (bottom left) The Canadian Press/Dave Buston; (bottom right)

The Prairie provinces continued to be subjected to destructive Laurentian policies throughout the 20th century, such as prolongation of the Canadian Wheat Board, official bilingualism and the National Energy Program, implemented by Pierre Trudeau in 1981 (shown on bottom left, to the right of Alberta premier Peter Lougheed in the centre). Depicted on bottom right, oil sands facility at Mildred Lake. (Sources of photos: (top left) Canadian Government Motion Picture Bureau/Library and Archives Canada/C-064834; (bottom left) The Canadian Press/Dave Buston; (bottom right)  “It’s not like Ottawa is a national government”: The Alberta Sovereignty within a United Canada Act, passed in late 2022 by the UCP government of Premier Danielle Smith, pictured, aims to strengthen the province’s ability to limit unconstitutional intrusions of federal policy and law into areas of provincial jurisdiction, thereby reaffirming that Canada is a federal state. (Source of photo: The Canadian Press/Jason Franson)

“It’s not like Ottawa is a national government”: The Alberta Sovereignty within a United Canada Act, passed in late 2022 by the UCP government of Premier Danielle Smith, pictured, aims to strengthen the province’s ability to limit unconstitutional intrusions of federal policy and law into areas of provincial jurisdiction, thereby reaffirming that Canada is a federal state. (Source of photo: The Canadian Press/Jason Franson) Although attacked by critics, Alberta’s Sovereignty Act has received strong popular support for challenging the Justin Trudeau government’s constant intrusions into areas of provincial constitutional jurisdiction; the author points out that the Constitution does not require provinces to enforce federal laws, and that the Supreme Court of Canada has confirmed this. Shown, supporters of the Sovereignty Act outside the Alberta legislature, December 2022. (Source of photo:

Although attacked by critics, Alberta’s Sovereignty Act has received strong popular support for challenging the Justin Trudeau government’s constant intrusions into areas of provincial constitutional jurisdiction; the author points out that the Constitution does not require provinces to enforce federal laws, and that the Supreme Court of Canada has confirmed this. Shown, supporters of the Sovereignty Act outside the Alberta legislature, December 2022. (Source of photo:  “Clear majority on a clear question”: Two years after the 1998 Quebec Secession Reference case before the Supreme Court of Canada, the Liberal government of Jean Chrétien (on bottom, leaning forward) introduced the Clarity Act, establishing the conditions under which Canadian provinces may be allowed to begin the process of secession. The author considers this another act violating the concept of federalism, with Ottawa unilaterally calling the shots and placing provinces in a subordinate position. (Sources of photos: (top)

“Clear majority on a clear question”: Two years after the 1998 Quebec Secession Reference case before the Supreme Court of Canada, the Liberal government of Jean Chrétien (on bottom, leaning forward) introduced the Clarity Act, establishing the conditions under which Canadian provinces may be allowed to begin the process of secession. The author considers this another act violating the concept of federalism, with Ottawa unilaterally calling the shots and placing provinces in a subordinate position. (Sources of photos: (top)