Next week, Ottawa will table its first budget in nearly two years. The government has already told us what to expect. In October, the Department of Finance announced a new “Capital Budgeting Framework” that would allow Canada to “spend less so it can invest more.” The phrasing sounds prudent. It is not. It is a linguistic sleight of hand designed to obscure what the government is actually doing: spending more while pretending to exercise restraint.

The older meanings of the two words reveal the moral inversion. To spend, from the Latin dispendere, meant to weigh out and let go. It implied the careful release of what one possessed, whether money, time, or energy. In Old English and Middle English, to “spend” one’s life or strength was to pour it out, knowingly and finitely. There was gravity to the act; what was spent was gone. To invest, by contrast, came from the Latin investīre: to clothe or cover. Before it became a financial term, it referred to the ceremonial act of placing robes upon a monarch or knight, endowing them with office or honour. In its financial sense, to invest was to “clothe money” in a venture, expecting return. The first word carried finality; the second, expectancy. Spending ended a possession; investing disguised it in the promise of future gain.

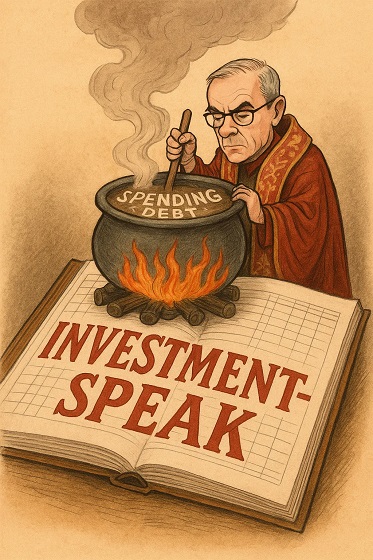

From these roots, the moral difference is clear. Spending belongs to the household, measured, finite, and real. Investing belongs to the court, symbolic, ceremonial, and often self-flattering. When a government calls its spending “investment,” it does not change the transaction; it changes the costume.

The gradual adoption of this vocabulary by governments is an old habit dressed as innovation. For two decades, Ottawa has been learning to speak the language of investment as disguise. Budgets that once tabulated “program spending” now announce “investments in Canadians.” Under the Trudeau governments, tax credits and subsidies were cast as “investments in innovation.” The Canada Infrastructure Bank was sold as “leveraging private investment” rather than public debt. Even emergency COVID programs were justified as “investing in recovery.” The word became a universal solvent, dissolving distinctions between cost, borrowing, and speculation.

This year’s government has merely made the trend official. In October, the Department of Finance released Modernizing Canada’s Budgeting Approach, explaining that the new Capital Budgeting Framework would “distinguish day-to-day operational spending from capital investment.” The document asserts that this will “guide decisions and help prioritize. The trick lies in the word “investment.” By separating “operational spending” from “capital investment,” Ottawa can now reclassify expenditures, moving them from one column to another without changing the underlying reality. A deficit remains a deficit. Borrowed money is still borrowed. But call it investment, and suddenly it carries the glow of foresight and responsibility. The government plans to balance its operating budget while continuing to borrow for capital projects. The ledger will grow, but the language will comfort.

This is not merely bad accounting. It is a deliberate corruption of language in service of political evasion. And it reveals something deeper about how modern governments govern: not through honest argument but through the manipulation of words.

Ottawa has been perfecting this costume for two decades. Budgets that once listed “program spending” now announce “investments in Canadians.” Tax credits became “investments in innovation.” The Canada Infrastructure Bank was sold as “leveraging private investment,” not public debt. COVID emergency programs were justified as “investing in recovery.” The word became a universal solvent, dissolving the distinction between cost, borrowing, and speculation.

This year’s framework makes the habit official. The October document from Finance Canada promises that the new approach will “guide decisions and help prioritize investments that generate long-term benefits for Canadians, such as major projects, housing, clean energy, and infrastructure.” The tone is managerial and assured. The assumption goes unexamined: that one can divide the public purse into virtuous investment and wasteful spending, and that the government possesses the wisdom to know the difference.

Haultain Research is a reader-supported publication.

To receive new posts and support our work, consider becoming a donor or a paid subscriber.

The Prime Minister echoed the line in his own announcement: “Budget 2025 will set out our plan to spend less so we can invest more in Canada’s long-term growth.” Read carefully, the statement reveals its own dishonesty. To “spend less” no longer means reducing outlays. It means shifting expenditures into a different category where they escape the stigma of cost. The government intends to continue borrowing, but it will refer to that borrowing by a supposedly more respectable name.

The definition of capital investment is conveniently broad. It includes tax credits, corporate subsidies, and nearly any policy “that contributes to capital formation.” The Fraser Institute and others have warned that this expansiveness allows Ottawa to reclassify politically favored programs as investment, inflating the appearance of fiscal discipline while reducing transparency. A deficit becomes a “generational investment.” A subsidy becomes a “partnership.” Waste is rebranded as “capacity-building.” The language does the work that policy cannot.

Recent history exposes the fraud. Consider the electric vehicle battery subsidies, heralded as “historic investments” in the green economy. Tens of billions were promised. Projects have stalled, been postponed, or quietly abandoned. The so-called green slush fund, officially presented as an investment vehicle for sustainable innovation, turned out to be a network of cronyism and waste. These, too, were dressed as investments. When their failures emerged, the language remained untouched, as though incompetence and corruption could not breach the sanctity of the term.

The alchemy works because language shapes perception faster than arithmetic. “Investment” suggests prudence and reward. “Spending” suggests indulgence and loss. Citizens hear that the government is “investing in Canadians” and imagine return, not depletion. The moral weight of the word does the political work. Accountability fades behind aspiration.

There is a deeper danger here. Words like spend and cost belong to the vocabulary of limits. They remind us that government operates with other people’s money. Invest, as politicians now use it, belongs to the vocabulary of boundless promise. It implies benevolence without constraint, as though the state were a benefactor rather than a borrower. When the government claims to “invest in Canadians,” it implies ownership of the very people whose money it spends. The inversion of subject and object is telling. It reveals the paternalism at the heart of modern technocracy.

George Orwell wrote that political language “is designed to make lies sound truthful and murder respectable.” He understood that the corruption of speech precedes the corruption of thought. When a government renames its spending as investment, it is not simply misdescribing an accounting category. It is reshaping the citizen’s perception of what government may do. If all spending is investment, then any limit on it seems stingy, even immoral. The citizen becomes debtor to a future defined by the state.

The deceit is subtle. No one disputes that bridges or power grids can be sound investments. The deceit lies in the implication that all government activity now yields return, that every expense is productive, every grant visionary. By this logic, no spending is considered waste and no deficit is deemed reckless, as long as it is labelled as an investment. The language abolishes the distinction between consumption and creation, between present sacrifice and future gain. In doing so, it abolishes prudence itself.

Prudence, in the older sense, is not caution for its own sake. It is moral realism: the recognition that resources are finite and choices have costs. The new investment rhetoric invites the opposite illusion. Money, once moralized as investment, appears to carry no weight of trade-off. Ottawa can clothe profligacy in the robes of responsibility. The government that promises to “spend less and invest more” is like a man claiming to drink less whiskey by pouring it into crystal.

The cost of this linguistic vanity is not only fiscal. It corrodes public trust. Citizens sense the dissonance. Deficits widen, taxes climb, promises multiply. When language becomes a substitute for honesty, cynicism follows. A people that cannot trust its government’s words cannot trust its numbers.

The remedy is simple, though seldom easy: call things by their names. Spending is spending, whether on roads, welfare, or research. Some are wise, some are foolish. But none becomes virtuous by relabeling. The duty of government is not to invent euphemisms but to justify expenditures plainly and bear the consequences. That is what accountability means.

Roger Scruton observed that conservatism, properly understood, is “the politics of the tried and tested against the politics of experiment.” In fiscal speech, that means preferring accuracy to allure. A government confident in its stewardship would not fear plain-spoken spending. Only one uneasy with its own excess needs the comfort of investment.

Ottawa’s linguistic reform is therefore not a matter of diction. It is an attempt to alter reality through language, to convert liability into virtue by decree. The danger is that citizens, lulled by investment-speak, will cease to notice the arithmetic beneath. The numbers will grow; the language will glow. By the time the robe is lifted, the treasury will be bare.

That is not a forecast. It is a warning. When governments clothe waste in the garments of investment, they are not modernizing accounting. They are modernizing deceit.

Share