Brownstone Institute

Evidence of Early Spread in the US: What We Know

From the Brownstone Institute

BY

In Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s short story “Silver Blaze,” Sherlock Holmes famously solved a murder case by noting a dog that didn’t bark.

Gregory (Scotland Yard detective to Holmes): “Is there any other point to which you would wish to draw my attention?”

Holmes: “To the curious incident of the dog in the night-time.”

Gregory: “The dog did nothing in the night-time.”

Holmes: “That was the curious incident.”

The “official” timeline of the spread of the novel coronavirus has been false from the very beginning. The “dog that didn’t bark” is the fact officials have refused to sincerely investigate the copious evidence of “early spread.”

When events and activities that clearly should have happened obviously did not happen, a truth-seeking detective would ask several common-sense questions.

For example: Why didn’t these activities take place? Are America’s trusted officials perhaps hiding something, and, if so, why? Should certain people and certain organizations be considered the primary suspects in one of the most shocking crimes in world history?

In previous articles, I identified 17 known Americans who possess antibody evidence of being infected by the novel coronavirus months before the virus was supposed to be circulating in America. Three of these Americans had antibody evidence of infection by November 2019.

I also recently identified at least seven other Americans who claim to have had Covid symptoms in November or December 2019 who state they later received positive antibody results. I’ve thus identified at least 24 known Americans who very likely had Covid at some point in the year 2019. Also and significantly, federal officials never interviewed any of these people.

Today’s deep dive into “early spread” evidence focusses on 106 other Americans who also had antibody evidence of early spread. These 106 Americans tested positive for Covid antibodies in a CDC study of Red Cross blood donors.

While the “Red Cross Blood Study” received a fair amount of media coverage when belatedly published on November 30, 2020, the “narrative-changing” or “seismic” implications of this study have still not been given the weight they deserve.

Conclusions flowing from this analysis include the following:

* By late December 2019, more than 7 million Americans had likely been infected by the coronavirus… more than three months before the lockdowns of mid-March 2020, lockdowns implemented to “slow” or “stop” the spread of a virus that had spread across the country and world many months earlier.

* “Probable” cases of Covid had already occurred in at least 16 U.S. states by January 1st, 2020 – weeks or months before the first “confirmed” case of Covid in America was recorded January 19, 2020.

- Antibody studies of archived blood in Italy and France also support the hypothesis that that virus had infected large numbers of people in these two nations as early as September 2019.

Key unanswered questions include:

Why was the Red Cross blood study the only antibody study of blood samples collected by blood bank organizations?

Why did it take so long to publish the results of this one Red Cross blood study?

When did officials test this blood and when did U.S. policy makers know the results?(This is literally a trillion-dollar question. Also, If this blood had been tested earlier, millions of lives might have been saved).

Why didn’t officials interview the 106 Americans who had antibody evidence of prior infection?

It’s possible at least some public health experts may have intentionally concealed evidence of early spread. Reasons prompting this disturbing conclusion are presented below.

The first known knowable

Between December 13-16, 2019, 1,912 Americans in the states of California, Oregon and Washington donated blood via the American Red Cross. Another 5,477 Americans also donated blood via the Red Cross between Dec. 30, 2019 and January 17, 2020. These donors were from the states of Massachusetts, Michigan, Rhode Island, Connecticut, Wisconsin and Iowa.

At some point, the CDC decided it should test these 7,389 samples of “archived” blood for Covid antibodies. When this took place – and why it took so long for this to happen – are two of many still-unanswered questions.

DISCUSSION – Tranche 1 (California, Oregon and Washington)

Of the 1,912 samples tested for Covid antibodies, 39 were positive for IgG and/or IgM antibodies.

The above represents 2.04 percent of the total samples from this tranche. In samples tested from the Red Cross’s Northern California district, 2.4 percent of the sera samples tested positive for Covid-19 via an ELISA assay.

If this was a representative sample of the American population, 2.04 percent would translate to approximately 7.94 million Americans who had already been infected by this virus in the weeks before Dec. 13-16. (Math: American population of 331 million x 0.024 percent = 7.94 million).

If we include both tranches, the 106 positive donors represents 1.43 percent of the larger “sample group.” This seroprevalence rate would translate to 4.73 million Americans nationwide being infected by some time in early January 2020.

We’re not supposed to perform this extrapolation

Public health officials working overtime to hype the fear factor must appreciate the fact journalists in the mainstream press did not perform the extrapolations I just performed above.

This particular “dog that didn’t bark” (a press that wouldn’t perform common-sense extrapolations) is probably explained by language/guidance the authors included in the study.

From the study: Findings “may not be representative of all blood donors or donations in these states and the findings may not be generalizable to all blood donors during the donation dates reported here. Therefore, population-based seroprevalence estimates or inference on magnitude of infections on a national or state level cannot be made.”

I did note the authors used the words “may not be generalizable to all blood donors during the donation dates reported here.” To me, this choice of words does not rule out the possibility these results may be generalizable to the larger population.

The authors’ reasons that readers should not “generalize” the results to the entire population are unconvincing. A random group of blood donors is about as good a sample as one can perform. For example, this was NOT a “biased” sample of people who thought they may have had Covid earlier.

This sample almost certainly undercounts virus prevalence in these states

In mainstream press stories about this study, all of them report as fact that this study dates the possible beginning of virus spread to December 2019. This is not accurate. The findings, for reasons outlined below, actually reveal that Americans were becoming infected in November 2019 or (almost-certainly) even earlier.

Regarding the possibility the sample may have under-counted true prevalence, the following points should be considered.

Some of the donors, especially those who had asymptomatic cases and never even knew they were sick, may not have had time to develop antibodies by the time they donated blood. Per one study, “the average time to detectable neutralization was 14.3 days post on-set of symptoms (range 3-59 days.)”

Also, it’s possible some of the donors may have had detectable levels of antibodies at an earlier date, but those antibodies had “waned” or “faded” and were no longer “detectable” at the time they gave blood samples.

Furthermore, all regular blood donors know that they should not donate blood if they have recently been sick. This deduction further backs up the possible date of infection for some “positive” donors by at least two weeks.

Also, backing up the true “infection date” of many of the donors is the fact that 32.23 percent of the donors who tested positive for “neutralizing antibodies” tested negative for the IgM antibody and positive for the IgG antibody.

Per many studies, IgM-positive antibodies only persist for approximately one month. That is, after 30 days, those who were previously infected by Covid will test negative for IgM antibodies. However, IgG antibodies can last for many months, years or, in some people, perhaps a lifetime.

Per the Red Cross study, 32 percent of donors were negative-IgM but positive IgG, which suggests that approximately one-third of this sample were infected a month or more before they donated blood. This combination of antibody results would push likely infection dates back to October (or even September) for some percentage of positive donors.

We don’t know when these people in the three Western states (or the other six Midwestern and Northeast states) may have been infected – but for probably most of them it would have been many weeks or even months before they donated blood.That is, the “Red Cross blood study” provides compelling evidence that early spread in America probably occurred by at least early October and perhaps even September.

What does the word ‘spread’ really mean?

Also, the fact that positive samples were found in ALL nine states (California, Oregon, Washington, Massachusetts, Michigan, Wisconsin, Iowa, Connecticut and Rhode Island) by itself strongly suggests virus “spread.” Question: How could a virus be infecting people in nine widely-dispersed states without first “spreading?”

To these nine states, we can add seven other states (New Jersey, Florida and Alabama) from my first round of stories and now also New York, Texas, Nebraska andNorth Carolina from my most recent story where readers with antibody evidence contacted me. This gives us 16 states where this allegedly non-existent or “isolated” virus had infected people before the first official case in America.

I would also note that whatever virus made many of these people “sick” spread between family members. For example, at least four married couples infected each other and/or at least one child. Mayor Michael Melham says “many” people at the conference where he first became sick with Covid symptoms also became sick at the same time, which, to this layman’s definition, connotes virus “spread.”

To the above numbers, we could add all the unknown individuals who infected these people … as well as the unknown individuals who infected these unknown individuals.

It should also be noted that the Red Cross blood study was not a perfect sample as blood donors are much older than the median age. In this sample, the median age was 52 – 13 years older than the U.S. median age of 38.6. Common sense tells us that older retirees do not interact with nearly as many people on a daily basis as more active younger people.

I’ve also come to believe it’s possible that officials who “authorized” or approved official antibody tests may have manipulated the tests to ensure fewer “confirmed” or “positive” cases, a result that would minimize any fallout from larger percentages of positives. A difference of 1 or 2 percent in seroprevalence estimates might not seem like much. However, in real terms, this would represent 3.3 to 6.6 million additional early cases.

For these reasons, I believe the number of Americans who’d been infected by the novel coronavirus in the year 2019 is notably higher than 1.43 or 2.04 percent of America’s population.

The Dog that Didn’t Bark Evidence

Regarding the Red Cross antibody study, several points deserve much greater attention than they’ve received. The following unanswered questions address these points:

Why was only ONE study of archived Red Cross blood performed?

By December 31, 2019, every American public health official was acutely aware that Chinese officials had reported an outbreak of a novel new type of “pneumonia” virus to the World Health Organization.

It’s my belief at least some U.S. officials either knew or had compelling reasons to suspect this months earlier. (This topic/theory will be explored in future articles).

Even if one accepts that the Dec. 31st notification was the first American officials had heard of a possible global pandemic, wouldn’t one of the first reactions of these officials be to test archived blood to see if this virus might have been spreading in this country?

One answer to this question might be that America’s scientific community simply did not have an antibody test capable of testing for antibodies in early January. This may be true, but, per my research, creating an antibody test for any virus poses no formidable challenge to smart and motivated scientists. If such an assay wasn’t available in the early weeks of the official pandemic, one should have certainly been available by the end of January.

Also, I’ve read several studies authored by Chinese scientists who were performing antibody tests in January 2020. For example, this study “was published on January 24, 2020” and includes the following sentence:

“Additional evidence to confirm the etiologic significance of 2019-nCoV in the Wuhan outbreak include … detection of IgM and IgG antiviral antibodies …”

Surely, in the face of an unfolding “global crisis,” America’s top scientific minds could have done the same thing (or just borrowed the technology from the Chinese).

The Red Cross didn’t have any more spare blood?

It must also be true that plenty of “archived” blood samples from throughout the country were available for testing (and the Red Cross is not the only organization that serves as a blood bank for hospitals).

In the face of a national emergency, it would seem odd if all of these organizations presented serious objections to some of their stored blood being “repurposed” for important research.

If two tranches of blood were donated for science, couldn’t other tranches of Red Cross blood have similarly been donated? Why was no Red Cross blood collected before December 13th tested for antibodies? Why was blood collected and tested from only nine states? Why not all 50 states? Why wasn’t blood from the same locations tested two or three weeks later (or from earlier dates) … or two months later to see if the percentage of positives might be increasing?

The public doesn’t know the answer to any of these questions and apparently no reporter asked officials these questions.

Again, projects that would seem like common-sense to most people … did NOT take place.

When did officials test this blood and when did U.S. policy makers know the results?

One piece of information not included in the report is the date the archived blood was finally tested. This is actually (and literally) a trillion-dollar question.

Another “known knowable” is the date in which lockdowns commenced – roughly March 13th 2020, the date Fauci, Birx et all “snuck in” the provisions of what the non-pharmaceutical intervention would actually entail (basically closing all non-essential businesses and organizations).

One might ask if the decision to lock down the country to “slow” or “stop’ the “spread” of this virus would have been authorized if it had been known that Americans in nine states already had antibody-evidence of infection by early January (or December or November)? Asked differently, if these results had been known by, say, late February 2020 how would officials justify the lockdowns?

Late February would be 73 days after the first tranche of Red Cross blood had been collected from donors and 58 days after the Wuhan Outbreak became known. How long does it really take to transport 1,900 units of blood to the CDC’s preferred testing lab and then test such a small batch of samples for antibodies? If this was a national emergency and scientists and lab workers were working 24-7, it would not have taken 58 days.

Perhaps the only reason this would not have occurred is that no member of the U.S. Scientific Bureaucracy thought of doing this …. a possibility this author finds hard to believe.

An alternative explanation is that officials intentionally delayed the testing of this blood so there would be no reason to call off the lockdowns. Here the assumption is that if Americans learned that many millions of Americans had already been infected with this virus by early December – and nobody in the entire country had even noticed – maybe the fear and panic that did ensue would not have ensued.

Why did it take so long to publish the results of this one Red Cross blood study?

Not only was the California-Washington-Oregon tranche of blood not tested in time to avert the lockdowns (at least as far as the public knows), the study that did take place wasn’t published until November 30, 2020. This was almost 12 months (!) after 1,900 people had donated blood Dec. 13-16.

In my research, I found numerous examples of serology studies that were conceived, conducted and the results published in a matter of weeks (In one case in Idaho in a matter of days).

Tucker Carlson thinks like I do

I’m a big fan of Tucker Carlson’s contrarian monologues, but I missed the fact he posed some of my same questions in a commentary that aired in the days after the Red Cross blood study was finally published.

Tucker: “So clearly, what we have been told for almost a year about the origins of the coronavirus is not true.

“Why are we just learning this now, a month after a presidential election? We’ve had reliable antibody tests since the summer, yet no one thought to test Red Cross blood samples until now?”

“Why weren’t elected officials demanding a coherent account of where this virus that has changed American history forever came from, how it got to the United States and how it spread through our population? Why don’t we know that yet?”

My only quibble with Tucker’s essay is that the American scientific community would have had “reliable” antibody tests far before “summer.”

(Another personal hypothesis: I also think “authorized” antibody tests were not made widely available until late April to conceal evidence of early spread, another theory I will expound on in a future article).

Carlson pointed out that as of December 2020, Americans still didn’t know where

this virus that “changed American history forever came from (or) how it got to the United States and how it spread through our population? Why don’t we know that yet?”

Carlson asked these questions two years ago … and Americans still have no answer.

As to Carlson’s question as to “why we don’t know that yet?” I can offer one possible answer: Because the people who know the answer must know that their fingerprints are on the creation of this virus. If the truth became known, they might be facing charges of “crimes against humanity.”

If the dog did bark and tell the sordid tale, it wouldn’t be one felon Sherlock Holmes nabbed, but a swamp full of felons. As it turns out, the felons are almost guaranteed protection by the massive numbers of accomplices (“stakeholders” in the authorized narrative) who are also interested in the truth never being revealed.

Why didn’t officials interview the 106 Americans who had antibody evidence of prior infection?

Any public health official genuinely interested in tracking down the earliest known cases would have rushed to interview every one of these 106 Americans.

The obvious goal would be to ascertain if any of these individuals happened to experience Covid-like symptoms weeks or months before they donated blood. If they had, available medical records (and perhaps even preserved tissue samples) might support this diagnosis. “Contact tracers” chasing down possible “Case Zeros” could have also found out if any of these individuals’ close contacts might have been sick.

But this did not happen (yet another dog that didn’t bark). Instead, we learn from the language in the study that blood donors were “de-identified” for unstated reasons.

Presumably, this was done to protect the medical privacy of these individuals. However, it’s hard to imagine a scenario where an American citizen in January or February 2020 would have been offended if a public servant investigating the origins of the century’s greatest pandemic asked him or her a few questions.

This hypothetical excuse would also be shown to be a canard by the fact that public health officials in France also performed an antibody study of archived stored blood. This study (summarized below) also found copious evidence of early spread, including French citizens who had antibody evidence of infection in early November 2019.

However, in France, unlike in America, public health officials did take the time to interview some of the positive subjects.

French Antibody Study found 3.9 percent of residents had antibody evidence of early spread

The French study selected and tested 9,144 serum samples collected betweenNovember 4, 2019 and March 16, 2020 in participants living in the 12 mainland French regions.

Three-hundred and fifty-three (3.9%) participants were ELISA-S positive, 138 were undetermined and 8653 were negative (undetermined and negative, 96.1%). The proportion of ELISA-S positive increased from 1.9% (42 of 2218) in November and 1.3% (20 of 1534) in December to 5.0% (114 of 2268) in January, 5.2% (114 of 2179) in February and 6.7% (63 or 945) in the first half of March.

A few observations/comments:

The percentage of positive samples (3.9 percent) of French participants is more than double the rate of the American Red Cross study (1.44 percent among 7,392 donors). The total number of positive cases (353) is more than three times greater than was found in the smaller Red Cross study (106 positive samples).

The American Red Cross study found “positives” in all nine states sampled and the French study found positives in all 12 mainland French regions … thus the results of both studies strongly suggest that the virus had spread across both countries.

In France, two percent (1.99 percent) of those studied had antibody evidence of infection by November 2019 – approximately four months before the global lockdowns. Perhaps surprisingly, the rates went down in December but then spiked to 5.0 percent in January and kept rising in February 5.2 percent) and had reached 6.7 percent in the first half of March (before the lockdowns).

The population of France in 2020 was 67.38 million. This means 6.7 percent of the population already had evidence of infection before the lockdowns commenced. Extrapolated to the entire French population, this would equate to 4.51 million French citizens. For context, the first three “confirmed” cases of Covid in France are still recorded as January 24, 2020.

No “pre-pandemic” serology study including archived blood collected in February 2020 was performed in America. If 5.2 percent of Americans had antibody evidence of infection by February (as was the case in France), this would equate to 17.21 million Americans.

French public officials did interview some early spread possibilities

From the study: “Participants with both ELISA-S and SN positive tests in serum sampled before February 1, 2020 were interviewed to identify potential exposure to SARS-CoV-2 infection. A trained investigator collected standardized information on clinical details … and any remarkable event in close contacts (e.g. unexplained pneumonia).

According to the French study, 13 people tested positive with “neutralizing antibodies” (a higher standard than just plain IgM or IgG positives) “between November 5, 2019 and January 30, 2020.”

“Table 1 describes the serological results in these 13 participants, among whom 11 were interviewed.

Of the 11 subjects who were interviewed, eight (8) – 73 percent – were either sick themselves or had close contacts with someone who was sick with Covid-like symptoms. For purposes of illustration, three of these individuals’ findings are presented below:

“Person 3 – Sampled in November 2019: Positive with Covid symptoms. Also noted: Her partner was sick with intense cough in October 2019 …”

“Person 6 – blood drawn November 2019 … Travel in Spain in early November. She had daily encounters with a family member who had a respiratory illness of unknown origin between October and December. She suffered from dysgeusia, hyposmia, and cough before the sample was taken, but could not remember the date of illness …”

“Person 7: Positive in November with symptoms. The participant and his partner were sick with a severe cough in October 2019. He had a follow-up serology at the end of July, 2020. ELISA-S = 3.82. (Note: This means this person received TWO positive antibody tests).

The above information provides another benefit of interviewing people who have antibody evidence of early infection – namely, officials can re-test these individuals at different points in the future to see how long antibodies last. Furthermore, if a large percentage of these early spread candidates did not later develop PCR-confirmed cases, this would suggest they do, in fact, have “natural immunity” (which would be further evidence of an earlier infection).

Italy Antibody Study is eye-opening

The most eye-opening “pre-pandemic” antibody study was carried out by a team of academic researchers in Italy.

The main text: “SARS-CoV-2 RBD-specific antibodies were detected in 111 of 959 (11.6%) individuals, starting from September 2019 (14%), with a cluster of positive cases (>30%) in the second week of February 2020 and the highest number (53.2%) in Lombardy. This study shows an unexpected very early circulation of SARS-CoV-2 among asymptomatic individuals in Italy several months before the first patient was identified, and clarifies the onset and spread of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.”

“Table 1 reports anti-SARS-CoV-2 RBD antibody detection according to the time of sample collection in Italy. In the first 2 months, September–October 2019, 23/162 (14.2%) patients in September and 27/166 (16.3%) in October displayed IgG or IgM antibodies, or both.”

“The first positive sample (IgM-positive) was recorded on September 3 in the Veneto region …

The 959 recruited patients came from all Italian regions, and at least one SARS-CoV-2–positive patient was detected in 13 regions – more evidence of wide-spread and “early,” person-to-person transmission.

More from the study: “Notably, two peaks of positivity for anti-SARS-CoV-2 RBD antibodies were visible: the first one started at the end of September, reaching 18% and 17% of IgM-positive cases in the second and third weeks of October, respectively. A second one occurred in February 2020, with a peak of over 30% of IgM-positive cases in the second week.”

According to the study’s authors: “Finding SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in asymptomatic people before the COVID-19 outbreak in Italy may reshape the history of pandemic.”

My comment: I’ve thought the same thing with all the articles I’ve written that presented copious evidence of “early spread.” However, I clearly thought wrong. Apparently, for some reason, the “early spread” dog ain’t barking.

Reprinted from the author’s Substack

Brownstone Institute

Bizarre Decisions about Nicotine Pouches Lead to the Wrong Products on Shelves

From the Brownstone Institute

A walk through a dozen convenience stores in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, says a lot about how US nicotine policy actually works. Only about one in eight nicotine-pouch products for sale is legal. The rest are unauthorized—but they’re not all the same. Some are brightly branded, with uncertain ingredients, not approved by any Western regulator, and clearly aimed at impulse buyers. Others—like Sweden’s NOAT—are the opposite: muted, well-made, adult-oriented, and already approved for sale in Europe.

Yet in the United States, NOAT has been told to stop selling. In September 2025, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued the company a warning letter for offering nicotine pouches without marketing authorization. That might make sense if the products were dangerous, but they appear to be among the safest on the market: mild flavors, low nicotine levels, and recyclable paper packaging. In Europe, regulators consider them acceptable. In America, they’re banned. The decision looks, at best, strange—and possibly arbitrary.

What the Market Shows

My October 2025 audit was straightforward. I visited twelve stores and recorded every distinct pouch product visible for sale at the counter. If the item matched one of the twenty ZYN products that the FDA authorized in January, it was counted as legal. Everything else was counted as illegal.

Two of the stores told me they had recently received FDA letters and had already removed most illegal stock. The other ten stores were still dominated by unauthorized products—more than 93 percent of what was on display. Across all twelve locations, about 12 percent of products were legal ZYN, and about 88 percent were not.

The illegal share wasn’t uniform. Many of the unauthorized products were clearly high-nicotine imports with flashy names like Loop, Velo, and Zimo. These products may be fine, but some are probably high in contaminants, and a few often with very high nicotine levels. Others were subdued, plainly meant for adult users. NOAT was a good example of that second group: simple packaging, oat-based filler, restrained flavoring, and branding that makes no effort to look “cool.” It’s the kind of product any regulator serious about harm reduction would welcome.

Enforcement Works

To the FDA’s credit, enforcement does make a difference. The two stores that received official letters quickly pulled their illegal stock. That mirrors the agency’s broader efforts this year: new import alerts to detain unauthorized tobacco products at the border (see also Import Alert 98-06), and hundreds of warning letters to retailers, importers, and distributors.

But effective enforcement can’t solve a supply problem. The list of legal nicotine-pouch products is still extremely short—only a narrow range of ZYN items. Adults who want more variety, or stores that want to meet that demand, inevitably turn to gray-market suppliers. The more limited the legal catalog, the more the illegal market thrives.

Why the NOAT Decision Appears Bizarre

The FDA’s own actions make the situation hard to explain. In January 2025, it authorized twenty ZYN products after finding that they contained far fewer harmful chemicals than cigarettes and could help adult smokers switch. That was progress. But nine months later, the FDA has approved nothing else—while sending a warning letter to NOAT, arguably the least youth-oriented pouch line in the world.

The outcome is bad for legal sellers and public health. ZYN is legal; a handful of clearly risky, high-nicotine imports continue to circulate; and a mild, adult-market brand that meets European safety and labeling rules is banned. Officially, NOAT’s problem is procedural—it lacks a marketing order. But in practical terms, the FDA is punishing the very design choices it claims to value: simplicity, low appeal to minors, and clean ingredients.

This approach also ignores the differences in actual risk. Studies consistently show that nicotine pouches have far fewer toxins than cigarettes and far less variability than many vapes. The biggest pouch concerns are uneven nicotine levels and occasional traces of tobacco-specific nitrosamines, depending on manufacturing quality. The serious contamination issues—heavy metals and inconsistent dosage—belong mostly to disposable vapes, particularly the flood of unregulated imports from China. Treating all “unauthorized” products as equally bad blurs those distinctions and undermines proportional enforcement.

A Better Balance: Enforce Upstream, Widen the Legal Path

My small Montgomery County survey suggests a simple formula for improvement.

First, keep enforcement targeted and focused on suppliers, not just clerks. Warning letters clearly change behavior at the store level, but the biggest impact will come from auditing distributors and importers, and stopping bad shipments before they reach retail shelves.

Second, make compliance easy. A single-page list of authorized nicotine-pouch products—currently the twenty approved ZYN items—should be posted in every store and attached to distributor invoices. Point-of-sale systems can block barcodes for anything not on the list, and retailers could affirm, once a year, that they stock only approved items.

Third, widen the legal lane. The FDA launched a pilot program in September 2025 to speed review of new pouch applications. That program should spell out exactly what evidence is needed—chemical data, toxicology, nicotine release rates, and behavioral studies—and make timely decisions. If products like NOAT meet those standards, they should be authorized quickly. Legal competition among adult-oriented brands will crowd out the sketchy imports far faster than enforcement alone.

The Bottom Line

Enforcement matters, and the data show it works—where it happens. But the legal market is too narrow to protect consumers or encourage innovation. The current regime leaves a few ZYN products as lonely legal islands in a sea of gray-market pouches that range from sensible to reckless.

The FDA’s treatment of NOAT stands out as a case study in inconsistency: a quiet, adult-focused brand approved in Europe yet effectively banned in the US, while flashier and riskier options continue to slip through. That’s not a public-health victory; it’s a missed opportunity.

If the goal is to help adult smokers move to lower-risk products while keeping youth use low, the path forward is clear: enforce smartly, make compliance easy, and give good products a fair shot. Right now, we’re doing the first part well—but failing at the second and third. It’s time to fix that.

Addictions

The War on Commonsense Nicotine Regulation

From the Brownstone Institute

Cigarettes kill nearly half a million Americans each year. Everyone knows it, including the Food and Drug Administration. Yet while the most lethal nicotine product remains on sale in every gas station, the FDA continues to block or delay far safer alternatives.

Nicotine pouches—small, smokeless packets tucked under the lip—deliver nicotine without burning tobacco. They eliminate the tar, carbon monoxide, and carcinogens that make cigarettes so deadly. The logic of harm reduction couldn’t be clearer: if smokers can get nicotine without smoke, millions of lives could be saved.

Sweden has already proven the point. Through widespread use of snus and nicotine pouches, the country has cut daily smoking to about 5 percent, the lowest rate in Europe. Lung-cancer deaths are less than half the continental average. This “Swedish Experience” shows that when adults are given safer options, they switch voluntarily—no prohibition required.

In the United States, however, the FDA’s tobacco division has turned this logic on its head. Since Congress gave it sweeping authority in 2009, the agency has demanded that every new product undergo a Premarket Tobacco Product Application, or PMTA, proving it is “appropriate for the protection of public health.” That sounds reasonable until you see how the process works.

Manufacturers must spend millions on speculative modeling about how their products might affect every segment of society—smokers, nonsmokers, youth, and future generations—before they can even reach the market. Unsurprisingly, almost all PMTAs have been denied or shelved. Reduced-risk products sit in limbo while Marlboros and Newports remain untouched.

Only this January did the agency relent slightly, authorizing 20 ZYN nicotine-pouch products made by Swedish Match, now owned by Philip Morris. The FDA admitted the obvious: “The data show that these specific products are appropriate for the protection of public health.” The toxic-chemical levels were far lower than in cigarettes, and adult smokers were more likely to switch than teens were to start.

The decision should have been a turning point. Instead, it exposed the double standard. Other pouch makers—especially smaller firms from Sweden and the US, such as NOAT—remain locked out of the legal market even when their products meet the same technical standards.

The FDA’s inaction has created a black market dominated by unregulated imports, many from China. According to my own research, roughly 85 percent of pouches now sold in convenience stores are technically illegal.

The agency claims that this heavy-handed approach protects kids. But youth pouch use in the US remains very low—about 1.5 percent of high-school students according to the latest National Youth Tobacco Survey—while nearly 30 million American adults still smoke. Denying safer products to millions of addicted adults because a tiny fraction of teens might experiment is the opposite of public-health logic.

There’s a better path. The FDA should base its decisions on science, not fear. If a product dramatically reduces exposure to harmful chemicals, meets strict packaging and marketing standards, and enforces Tobacco 21 age verification, it should be allowed on the market. Population-level effects can be monitored afterward through real-world data on switching and youth use. That’s how drug and vaccine regulation already works.

Sweden’s evidence shows the results of a pragmatic approach: a near-smoke-free society achieved through consumer choice, not coercion. The FDA’s own approval of ZYN proves that such products can meet its legal standard for protecting public health. The next step is consistency—apply the same rules to everyone.

Combustion, not nicotine, is the killer. Until the FDA acts on that simple truth, it will keep protecting the cigarette industry it was supposed to regulate.

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoThe Liberal budget is a massive FAILURE: Former Liberal Cabinet Member Dan McTeague

-

COVID-192 days ago

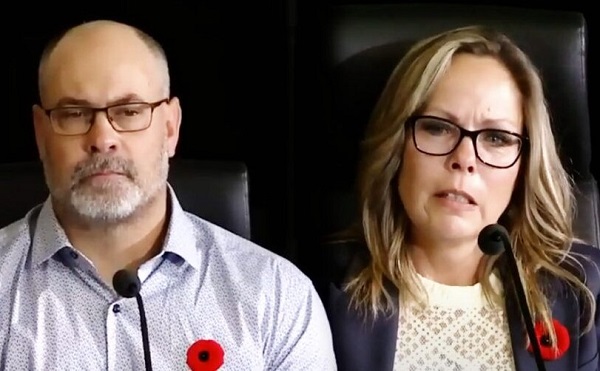

COVID-192 days agoFreedom Convoy leader Tamara Lich to appeal her recent conviction

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoCarney’s budget spares tax status of Canadian churches, pro-life groups after backlash

-

Justice2 days ago

Justice2 days agoCarney government lets Supreme Court decision stand despite outrage over child porn ruling

-

Daily Caller1 day ago

Daily Caller1 day agoUN Chief Rages Against Dying Of Climate Alarm Light

-

espionage1 day ago

espionage1 day agoU.S. Charges Three More Chinese Scholars in Wuhan Bio-Smuggling Case, Citing Pattern of Foreign Exploitation in American Research Labs

-

Business21 hours ago

Business21 hours agoCarney budget doubles down on Trudeau-era policies

-

COVID-1921 hours ago

COVID-1921 hours agoCrown still working to put Lich and Barber in jail