Community

Difference between politicians and bureaucrats is important.

The main difference between politicians and bureaucrats is that politicians worry about results and the bureaucrats worry about the process. Who do we want to take the leadership role?

For several years after the Conservatives were elected to govern, journalists and M Ps were going on about boys in short pants from the PMO were running the show, telling M Ps, Cabinet Ministers and Senators what to say and who to talk with. For Canadians it was extremely frustrating seeing our elected officials becoming bobble headed puppets spewing prepared talking points.

This was the most obvious example but the same was happening with Premiers and Mayors, across the country.

The result is distressing as governments grew, and with more and more bureaucrats specialized in more restricted areas, the bigger picture got lost. We end up with bubbles, the Ottawa bubble, the provincial capital bubbles, and the city hall bubbles. Most bureaucrats live near where they work, and politicians seldom do, living in ridings a fair distance away. Bureaucrats stay while politicians come and go.

Even in city halls, it often seen in how or where the elected officials are treated and situated in the building or in the hierarchy. Management is symbolically raised above the elected councillors, and nearer the centre of power. Chances are the councillors will be separated from the mayor by departments, floors or wings.

There is a separation between politicians and bureaucrats and a need to separate the governance from the operations and that is understandable. But it is when the governing officials are treated as less than equal, you create the systemic and chronic problems. It has been known, that Prime Ministers treat their M Ps with little respect, relying on bureaucrats in the PMO, Premiers treat MLAs in the same manner, and often times Mayors treat the councillors, so it appears we become govern by bureaucrats.

How do we accomplish anything? Who do we talk to with our personal issue or concern? You can seek out a high level bureaucrat or you can find an Advocate to raise the profile of the issue. Advocacy groups can be very effective, the Downtown Business Association is very effective and it has the extra bonus of having city hall located within it’s boundaries.

The Canadian Taxpayers Association, seems like a good start but they have a limited membership and a limited scope, basically not paying taxes, so they will not help the single tax payer in distress. They have a lot of money and influence, but are not really representative of the Canadian taxpayers. Like many advocacy groups they restrict themselves to certain issues.

Every bureaucrat and department has a drawer or file for issues or project to languish and be forgotten. That issue you discussed with your elected official, who supported your cause, probably went into that drawer or file, never to be seen again. The elected official, went on to the next person, and the cycle continues.

Individually, we are shackled to a system, created and nurtured by bureaucrats, and we hope will be changed, altered and improved after every election. It seldom changes. Listen to or watch the Prime Minister, Premiers or Mayors after an issue arises, and where they turn to for advice? Seldom an elected official but their closest bureaucrat, which will be brought forward to the elected officials, usually as a fait d’accompli. Except in some minority governments, where they have to earn support.

So, if the bureaucrats, run the show, why do we bother with the time and costs of having elections? Why not just elect a Mayor, a Premier and a Prime Minister? The Mayors could meet chaired by the Premier, then the Premiers could meet and be chaired by the Prime Minister. It would be cheaper, but it would destroy an illusion of democratic equality.

Perhaps, our politicians could remember why they are there, demand equality and not accept being dismissed by other political offices and bureaucrats, and take over leadership roles. Then this letter would not be needed, but unfortunately, it is needed now. I think the result is the more important and the process is there to achieve the needed result. That I think has been forgotten.

Politicians, please remember why you were elected? It was to lead, not to get lost in the process. Can you do that, because we need you to? Burst those bubbles and represent your constituents, the process will adapt, if you do. Thank you.

Community

Support local healthcare while winning amazing prizes!

|

|

|

|

|

|

Community

SPARC Caring Adult Nominations now open!

Check out this powerful video, “Be a Mr. Jensen,” shared by Andy Jacks. It highlights the impact of seeing youth as solutions, not problems. Mr. Jensen’s patience and focus on strengths gave this child hope and success.

👉 Be a Mr. Jensen: https://buff.ly/8Z9dOxf

Do you know a Mr. Jensen? Nominate a caring adult in your child’s life who embodies the spirit of Mr. Jensen. Whether it’s a coach, teacher, mentor, or someone special, share how they contribute to youth development. 👉 Nominate Here: https://buff.ly/tJsuJej

Nominate someone who makes a positive impact in the live s of children and youth. Every child has a gift – let’s celebrate the caring adults who help them shine! SPARC Red Deer will recognize the first 50 nominees. 💖🎉 #CaringAdults #BeAMrJensen #SeePotentialNotProblems #SPARCRedDeer

s of children and youth. Every child has a gift – let’s celebrate the caring adults who help them shine! SPARC Red Deer will recognize the first 50 nominees. 💖🎉 #CaringAdults #BeAMrJensen #SeePotentialNotProblems #SPARCRedDeer

-

Addictions1 day ago

Addictions1 day agoWhy B.C.’s new witnessed dosing guidelines are built to fail

-

Frontier Centre for Public Policy2 days ago

Frontier Centre for Public Policy2 days agoCanada’s New Border Bill Spies On You, Not The Bad Guys

-

Business1 day ago

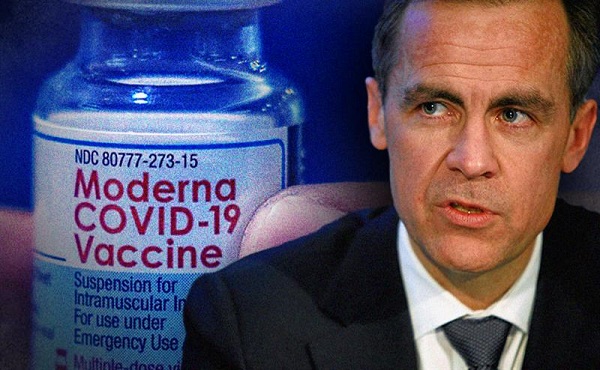

Business1 day agoCarney Liberals quietly award Pfizer, Moderna nearly $400 million for new COVID shot contracts

-

Energy2 days ago

Energy2 days agoCNN’s Shock Climate Polling Data Reinforces Trump’s Energy Agenda

-

Opinion1 day ago

Opinion1 day agoPreston Manning: Three Wise Men from the East, Again

-

Opinion1 day ago

Opinion1 day agoCharity Campaigns vs. Charity Donations

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoMark Carney’s Fiscal Fantasy Will Bankrupt Canada

-

COVID-191 day ago

COVID-191 day agoTrump DOJ dismisses charges against doctor who issued fake COVID passports