Business

Court ruling gives DOGE green light on federal data sweep

Quick Hit:

A federal appeals court has cleared the way for the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) to access sensitive data from multiple federal agencies, overturning a lower court’s block and aligning with a recent Supreme Court decision on similar Social Security records.

Key Details:

- The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit granted DOGE access to data from the Treasury, Education, and Office of Personnel Management.

- The majority opinion cited a June Supreme Court order allowing DOGE to review Social Security records.

- Critics, including labor unions and Judge Robert B. King in dissent, warn of privacy risks and lack of transparency in DOGE’s operations.

Diving Deeper:

On Tuesday, a Fourth Circuit panel handed the Trump administration’s Department of Government Efficiency a significant win, granting its analysts access to personal data housed at several major federal agencies. The decision overturns a February lower court ruling that had blocked such access and comes just weeks after the Supreme Court allowed DOGE to continue reviewing Social Security data.

The 2-1 ruling, authored by Judge Julius N. Richardson, a Trump appointee, and joined by Judge G. Steven Agee, appointed by President George W. Bush, permits DOGE teams to pull data from the Treasury Department, the Department of Education, and the Office of Personnel Management. These databases hold a wide array of personal details—from addresses and employer records to student loan data for more than 40 million borrowers.

Judge Richardson argued the case closely mirrored the Supreme Court’s recent emergency decision, which granted DOGE “high-level I.T. access” to agency databases to carry out its mission. The administration maintains DOGE’s purpose is to scrutinize federal records for waste, duplication, and fraud—efforts President Trump has made a cornerstone of his push to downsize Washington’s bureaucracy.

Labor unions, however, contend that DOGE’s sweeping authority violates federal privacy laws. They warn that such access could expose sensitive information and lacks sufficient safeguards. Judge Robert B. King, a Clinton appointee, issued a sharp dissent, criticizing the “sudden, unfettered, unprecedented” access to millions of Americans’ personal records and defending the lower court’s caution.

While Elon Musk, who helped establish DOGE, stepped down in May, the department has continued operating largely in the shadows, pursuing what opponents describe as an aggressive agenda to shrink federal agencies and limit the scope of government services. As legal challenges play out, the judiciary has increasingly sided with DOGE—an outcome that strengthens the administration’s hand in reshaping the federal apparatus.

“Theodore Roosevelt Federal Building – Washington D.C.” by Tony Webster licensed under (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Business

The EU Insists Its X Fine Isn’t About Censorship. Here’s Why It Is.

Europe calls it transparency, but it looks a lot like teaching the internet who’s allowed to speak.

|

When the European Commission fined X €120 million on December 5, officials could not have been clearer. This, they said, was not about censorship. It was just about “transparency.”

They repeat it so often you start to wonder why.

The fine marks the first major enforcement of the Digital Services Act, Europe’s new censorship-driven internet rulebook.

It was sold as a consumer protection measure, designed to make online platforms safer and more accountable, and included a whole list of censorship requirements, fining platforms that don’t comply.

The Commission charged X with three violations: the paid blue checkmark system, the lack of advertising data, and restricted data access for researchers.

None of these touches direct content censorship. But all of them shape visibility, credibility, and surveillance, just in more polite language.

Musk’s decision to turn blue checks into a subscription feature ended the old system where establishment figures, journalists, politicians, and legacy celebrities got verification.

The EU called Musk’s decision “deceptive design.” The old version, apparently, was honesty itself. Before, a blue badge meant you were important. After, it meant you paid. Brussels prefers the former, where approved institutions get algorithmic priority, and the rest of the population stays in the queue.

The new system threatened that hierarchy. Now, anyone could buy verification, diluting the aura of authority once reserved for anointed voices.

Reclaim The Net is sustained by its readers.

Your support fuels the fight for privacy, free speech and digital civil liberties while giving you access to exclusive content, practical how to guides, premium features and deeper dives into freedom-focused tech.

Become a supporter here.

However, that’s not the full story. Under the old Twitter system, verification was sold as a public service, but in reality it worked more like a back-room favor and a status purchase.

The main application process was shut down in 2010, so unless you were already famous, the only way to get a blue check was to spend enough money on advertising or to be important enough to trigger impersonation problems.

Ad Age reported that advertisers who spent at least fifteen thousand dollars over three months could get verified, and Twitter sales reps told clients the same thing. That meant verification was effectively a perk reserved for major media brands, public figures, and anyone willing to pay. It was a symbol of influence rationed through informal criteria and private deals, creating a hierarchy shaped by cronyism rather than transparency.

Under the new X rules, everyone is on a level playing field.

Government officials and agencies now sport gray badges, symbols of credibility that can’t be purchased. These are the state’s chosen voices, publicly marked as incorruptible. To the EU, that should be a safeguard.

The second and third violations show how “transparency” doubles as a surveillance mechanism. X was fined for limiting access to advertising data and for restricting researchers from scraping platform content. Regulators called that obstruction. Musk called it refusing to feed the censorship machine.

The EU’s preferred researchers aren’t neutral archivists. Many have been documented coordinating with governments, NGOs, and “fact-checking” networks that flagged political content for takedown during previous election cycles.

They call it “fighting disinformation.” Critics call it outsourcing censorship pressure to academics.

Under the DSA, these same groups now have the legal right to demand data from platforms like X to study “systemic risks,” a phrase broad enough to include whatever speech bureaucrats find undesirable this month.

The result is a permanent state of observation where every algorithmic change, viral post, or trending topic becomes a potential regulatory case.

The advertising issue completes the loop. Brussels says it wants ad libraries to be fully searchable so users can see who’s paying for what. It gives regulators and activists a live feed of messaging, ready for pressure campaigns.

The DSA doesn’t delete ads; it just makes it easier for someone else to demand they be deleted.

That’s how this form of censorship works: not through bans, but through endless exposure to scrutiny until platforms remove the risk voluntarily.

The Commission insists, again and again, that the fine has “nothing to do with content.”

That may be true on a direct level, but the rules shape content all the same. When governments decide who counts as authentic, who qualifies as a researcher, and how visibility gets distributed, speech control doesn’t need to be explicit. It’s baked into the system.

Brussels calls it user protection. Musk calls it punishment for disobedience. This particular DSA fine isn’t about what you can say, it’s about who’s allowed to be heard saying it.

TikTok escaped similar scrutiny by promising to comply. X didn’t, and that’s the difference. The EU prefers companies that surrender before the hearing. When they don’t, “transparency” becomes the pretext for a financial hammer.

The €120 million fine is small by tech standards, but symbolically it’s huge.

It tells every platform that “noncompliance” means questioning the structure of speech the EU has already defined as safe.

In the official language of Brussels, this is a regulation. But it’s managed discourse, control through design, moderation through paperwork, censorship through transparency.

And the louder they insist it isn’t, the clearer it becomes that it is.

|

|

|

|

Reclaim The Net Needs Your

With your help, we can do more than hold the line. We can push back. We can expose censorship, highlight surveillance overreach, and amplify the voices of those being silenced.

If you have found value in our work, please consider becoming a supporter.

Your support does more than keep us independent. It also gives you access to exclusive content, deep dive exploration of freedom focused technology, member-only features, and practical how-to posts that help you protect your rights in the real world.

You help us expand our reach, educate more people, and continue this fight.

Please become a supporter today.

Thank you for your support.

|

Business

Loblaws Owes Canadians Up to $500 Million in “Secret” Bread Cash

Yakk Stack

(Only 5 Days Left!) Claim Yours Before It’s GONE FOREVER

Hey, all.

Imagine this…you’re slicing into that fresh loaf from Loblaws or just making a Wonder-ful sammich, the one you’ve bought hundreds of times over the years, and suddenly… ka-ching!

A fat check lands in your mailbox.

Not from a lottery ticket, not from a side hustle – from the very store that’s been quietly owing you money for two decades of illegal price fixing.

Sound too good to be true?

It’s real.

It’s court-approved.

And right now, on December 7, 2025, you’ve got exactly 5 days to grab your share before the door slams shut. Don’t let this slip away – keep reading, feel that spark of possibility ignite, and let’s get you paid.

Back in 2001, you were probably juggling work, kids, or just surviving on that weekly grocery run. Little did you know, while you were reaching for the President’s Choice white bread or those golden rolls, Loblaws and their cronies were playing a sneaky game of price-fixing. They jacked up the cost of packaged bread across Canada – every loaf, every bun, every sneaky sandwich slice. For 20 years. From coast to coast to coast.

And now…the courts have spoken. $500 million in settlements to make it right. That’s not pocket change – that’s your money, recycled back into your life.

Given the number of people who will be throwing in a claim…this ain’t gunna be life-changing cash…but also, given the cost of food in Canada, it’s better than sweet fuck all, which you will receive by NOT doing this.

If you’re a Canadian resident (yep, that’s you, unless you’re in Quebec with your own sweet deal), and you’ve ever bought bread for your family – not for resale, just real life – between January 1, 2001, and December 31, 2021… you’re in.

No receipts needed.

No fancy proofs.

Just you, confirming your story, and boom – eligible.

Quick check: Were you under 18 back then?

Or an exec at Loblaw?

Nah, skip it.

But for the rest of us everyday schleps…Jackpot.

Again…the clock’s ticking on this.

Claims opened on September 11, 2025, and slam shut on December 12, 2025.

That’s this Friday.

Payments roll out in 2026, 6-12 months later, straight to your bank or mailbox.

Here’s what you need to do…

- Breathe deep, click → HEREQuebec frens →HERE

- 10 second form that’s completed by your autofill…30 seconds off of a mobile device.

- Hit submit and wait for that sweet cash to hit your account.

Again…this won’t be life saving money and most certainly ain’t gunna hit your account before Christmas.

And before you go out an Griswald yourself into a depost on pool in the backyard…you may only end up with enough cash for the Jam-of-the-Month…the gift that truly does give, all year round…just be a little patient.

If you end up with a couple of backyard steaks in time for summer…

Some treats for the children or grandchildren…

Maybe just a donation to the foodbank…

This is what’s owed to you. Your neighbors. Friends. Family.

Take advantage!

-

MAiD1 day ago

MAiD1 day agoFrom Exception to Routine. Why Canada’s State-Assisted Suicide Regime Demands a Human-Rights Review

-

Automotive2 days ago

Automotive2 days agoPower Struggle: Governments start quietly backing away from EV mandates

-

Business1 day ago

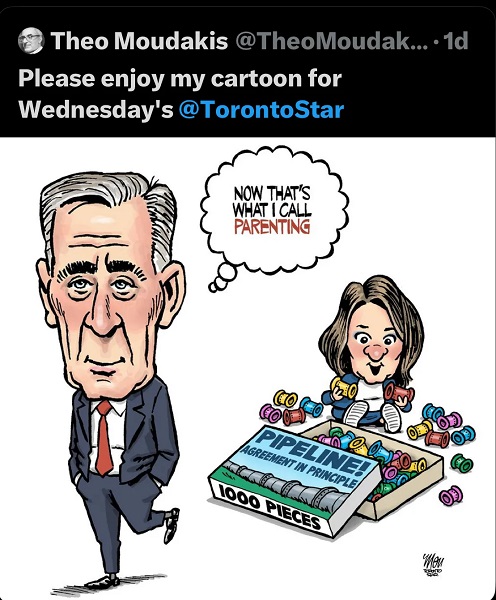

Business1 day agoCarney government should privatize airports—then open airline industry to competition

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoNew Chevy ad celebrates marriage, raising children

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoWhat’s Going On With Global Affairs Canada and Their $392 Million Spending Trip to Brazil?

-

Energy1 day ago

Energy1 day agoCanada following Europe’s stumble by ignoring energy reality

-

Censorship Industrial Complex2 days ago

Censorship Industrial Complex2 days agoFrances Widdowson’s Arrest Should Alarm Every Canadian

-

Aristotle Foundation2 days ago

Aristotle Foundation2 days agoThe extreme ideology behind B.C.’s radical reconciliation agenda