Crime

Chinese Narco Suspect Caught in Private Meeting with Trudeau, Investigated by DEA, Linked to Panama, Caribbean, Mexico – Police Sources

Sam Cooper

Sam Cooper

Shocking new details are emerging about a major Chinese organized crime suspect who met privately with Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, according to a police source who confirmed recent reporting from The Globe and Mail. The individual, Paul King Jin, is allegedly implicated in money laundering operations spanning the Western Hemisphere and has been a target of multiple failed major investigations in British Columbia. These investigations sought to unravel the complex interrelations of underground casinos and real estate investment, fentanyl and methamphetamine trafficking, and financial crimes that allegedly funnel drug proceeds from diaspora community underground banks throughout North America and Latin America, with connections to Chinese and Hong Kong financial institutions.

The failed investigations into Jin have involved both the RCMP and U.S. agencies. These operations stretch from Vancouver to Mexico, Panama, and beyond, multiple sources confirm.

Repeated efforts to reach Jin for comment through his lawyer in the British Columbia Cullen Commission, which stemmed from investigative journalism exposing BC casino money laundering, have not been successful. Recent BC civil forfeiture filings seeking to seize alleged money laundering proceeds from Jin, with cases connecting 14 Vancouver homes to entities in Hong Kong and China, also indicate Jin has not been responsive through a lawyer.

Highlighting longstanding U.S. government concerns over the B.C. investigations and suspects like Jin, Mayor Brad West confirmed in exclusive interviews with The Bureau that U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken expressed dismay over Canada’s failure to successfully prosecute Jin and Chinese crime networks, specifically citing the collapse of the E-Pirate investigation. Reportedly Canada’s largest-ever probe into money laundering, E-Pirate fell apart in court after cooperating witnesses were exposed. One of the Chinese Triad narcotics traffickers targeted in E-Pirate surveillance, Richard Yen Fat Chiu, was found stabbed and burned to death near the Venezuelan border on June 20, 2019, according to Colombian news reports.

The Bureau has verified with a source possessing direct knowledge of Canadian policing failures that crucial intelligence regarding Sam Gor—a massive transnational crime syndicate—was provided to the RCMP by U.S. agencies yet failed to result in prosecutions.

One primary source confirmed a new detail reported by The Globe and Mail: Prime Minister Justin Trudeau was entangled in an RCMP surveillance operation that targeted Paul Jin and the Sam Gor networks in Richmond, British Columbia. The Globe reported that early in his tenure, Trudeau met with Jin at a closed-door gathering at the Executive Inn Express Richmond, near Vancouver International Airport. Three sources corroborated the meeting according to The Globe, which took place between late 2015 and early 2017. Also present at the meeting was a Chinese army veteran with close ties to Beijing. The Globe noted that the veteran had attended social events with Chinese diplomats, reinforcing concerns about political and security risks posed by these associations.

The Bureau’s police source, who is independent of The Globe’s sources, confirmed they were aware of the RCMP surveillance operation that placed Trudeau, Jin, and the Chinese army veteran together in a private meeting.

Meanwhile, Jin himself has been surveilled in meetings with Chinese police officers who have traveled to Richmond, according to a separate police source with extensive knowledge of Chinese organized crime and influence operations in Canada. Two sources further stated that Jin continues to operate underground casino networks in Richmond, where law enforcement intelligence believes he has erected a mansion using front owners. Membership at this establishment is reportedly set at $100,000 for high-rollers.

According to a criminal intelligence source, Jin has alleged ties to China’s Ministry of Public Security and the network of clandestine Chinese police stations in British Columbia investigated by the RCMP. Two sources confirmed that Jin has allegedly acquired a new luxury mansion in Richmond, registered under a nominee—an established organized crime tactic.

“Jin uses one of his flunkies as a nominee for it. Common practice,” the source said. They further alleged that one of Jin’s associates tied to the mansion was implicated with Jin in a significant 2009 methamphetamine investigation. “Again, the use of nominees for real estate and businesses. Organized crime 101.”

Jin’s activities extend well beyond Canada, two sources alleged.

“He’s spending a lot of time in Latin America and the Caribbean,” a source said. “Asian organized crime is running amok. Foreign actor interference is getting really established. How it works is the current government welcoming any contributions from the motherland. What does this have to do with Asian organized crime in Canada? There’s a trade connection now from those areas in Latin America and the Caribbean to Canadian Asian organized crime commodity trades, primarily via the Maritimes.”

Jin has also been linked to international criminal networks, with two sources indicating that he and other high-level Canadian Triad associates have been traveling extensively to Panama and other Latin American jurisdictions. These movements align with intelligence connecting Canadian Triads to Mexican cartel operatives, facilitating narcotics trafficking, money laundering, and commodity smuggling into the United States.

Panama, which Trump administration State Secretary Marco Rubio has flagged as a hub of Chinese crime and state influence, has emerged as a focal point for Jin’s operations. “Jin was spending an awful lot more time down in Panama, where we think he is putting a lot of his capital there,” a source familiar with North American law enforcement investigations said. “They have the same kind of problem going on in Panama City as Vancouver, with all of the condo towers, and they’re empty. So people are plowing money into that place too.”

Adding to the concerns, a source disclosed that Jin’s travels to Panama raised red flags within international law enforcement circles. Jin flew from Vancouver to Toronto, then to Mexico City, Colombia, and finally Panama. Upon arrival, Panamanian customs flagged discrepancies in his travel documents, detecting an alternate identity. He was deemed inadmissible and promptly deported along the same route back to Canada.

“They said, ‘No, you’re inadmissible. Something’s wrong here. You’re traveling under this name, but we have you here as another person.’ So Panama punted him and sent him back exactly the same route, and we caught wind of this because of the liaison office down in Bogota,” the source, who could not be identified due to sensitivities in Canada, said. “And they let us know, and locally, the CBSA guys let the Toronto guys know because that’s where he would clear Canada Customs coming back. So they were like, ‘Okay, this is worthy of an interview.’ And they put a flag in the system and everything else.

“To make a long story short, it all fell flat. Nobody interviewed him. He just came right back—came right back to his place here in Vancouver. And so it just shows you the brokenness of our own system, that we can’t even get a key guy like that consistently checked and stopped, and he’s traveling under false papers.”

Jin’s expanding influence in Panama is a significant development aligning with Trump administration concerns, the source said, underscoring broader fears about China’s growing criminal and political footprint in the Western Hemisphere.

The Bureau previously reported that the latest BC civil forfeiture case—the fourth against Jin in three years—suggests he is actively evading British Columbia court procedures. Court filings state that after being banned from British Columbia casinos, Paul King Jin shifted his operations to illegal gaming houses, generating over $32 million in just four months in 2015. These underground casinos became a crucial node in a cash-based network fueling the proliferation of synthetic drugs across North America.

The case intensified in November 2022 when Everwell Knight Limited, a Hong Kong-registered entity holding mortgages on 14 disputed properties linked to Jin, sought to dismiss the government’s forfeiture claim on procedural grounds. Everwell’s legal team invoked the Canadian Charter of Rights—an increasingly common legal strategy in Canadian money laundering cases—arguing that the Director of Civil Forfeiture had failed to meet procedural requirements.

In April 2023, the Director of Civil Forfeiture responded with a default judgment application, contending that Jin’s failure to file a defense effectively conceded key allegations. The case also underscored Jin’s pattern of evasion, with the Director’s counsel noting that an unnamed lawyer initially suggested they might represent Jin but then ceased communication, leaving his legal status unresolved.

Regarding another key Sam Gor associate, E-Pirate target Richard Chiu—the Vancouver-area drug kingpin found burned and stabbed in 2019 near Cúcuta, a city close to the Colombian border with Venezuela—Chiu had previously been convicted in Massachusetts in 2002 for conspiracy to distribute and possess heroin.

According to B.C. Supreme Court documents, Chiu was the subject of multiple Vancouver police drug investigations. In 2017, during one such probe, authorities surveilled an Audi Q7 leased to him. Civil forfeiture filings state that police observed Chiu’s wife, Kimberly Chiu, exiting the vehicle while a “known gang associate” placed a heavy bag into the trunk.

Kimberly Chiu later became the subject of a civil forfeiture case after police seized $317,000 from the Audi—most of it packed in vacuum-sealed bundles inside a duffel bag. However, unlike other suspects, Richard Chiu was never criminally charged in Canada or directly sued by the director of civil forfeiture.

The government’s statement of claim alleged that Kimberly Chiu was “acting as a courier for Asian organized crime,” a claim she denied. In her defense, she argued that Vancouver police had no lawful grounds to detain or search her.

The collapse of E-Pirate and related Canadian law enforcement failures prompted then-B.C. Attorney General David Eby to launch a review, but it led to no legal reforms or policy changes in the province.

Crime

The Uncomfortable Demographics of Islamist Bloodshed—and Why “Islamophobia” Deflection Increases the Threat

Addressing realities directly is the only path toward protecting communities, confronting extremism, and preventing further loss of life, Canadian national security expert argues.

After attacks by Islamic extremists, a familiar pattern follows. Debate erupts. Commentary and interviews flood the media. Op-eds, narratives, talking points, and competing interpretations proliferate in the immediate aftermath of bloodshed. The brief interval since the Bondi beach attack is no exception.

Many of these responses condemn the violence and call for solidarity between Muslims and non-Muslims, as well as for broader societal unity. Their core message is commendable, and I support it: extremist violence is horrific, societies must stand united, and communities most commonly targeted by Islamic extremists—Jews, Christians, non-Muslim minorities, and moderate Muslims—deserve to live in safety and be protected.

Yet many of these info-space engagements miss the mark or cater to a narrow audience of wonks. A recurring concern is that, at some point, many of these engagements suggest, infer, or outright insinuate that non-Muslims, or predominantly non-Muslim societies, are somehow expected or obligated to interpret these attacks through an Islamic or Muslim-impact lens. This framing is frequently reinforced by a familiar “not a true Muslim” narrative regarding the perpetrators, alongside warnings about the risks of Islamophobia.

These misaligned expectations collide with a number of uncomfortable but unavoidable truths. Extremist groups such as ISIS, Al-Qaeda, Hamas, Hezbollah, and decentralized attackers with no formal affiliations have repeatedly and explicitly justified their violence through interpretations of Islamic texts and Islamic history. While most Muslims reject these interpretations, it remains equally true that large, dynamic groups of Muslims worldwide do not—and that these groups are well prepared to, and regularly do, use violence to advance their version of Islam.

Islamic extremist movements do not, and did not, emerge in a vacuum. They draw from the broader Islamic context. This fact is observable, persistent, and cannot be wished or washed away, no matter how hard some may try or many may wish otherwise.

Given this reality, it follows that for most non-Muslims—many of whom do not have detailed knowledge of Islam, its internal theological debates, historical divisions, or political evolution—and for a considerable number of Muslims as well, Islamic extremist violence is perceived as connected to Islam as it manifests globally. This perception persists regardless of nuance, disclaimers, or internal distinctions within the faith and among its followers.

THE COST OF DENIAL AND DEFLECTION

Denying or deflecting from these observable connections prevents society from addressing the central issues following an Islamic extremist attack in a Western country: the fatalities and injuries, how the violence is perceived and experienced by surviving victims, how it is experienced and understood by the majority non-Muslim population, how it is interpreted by non-Muslim governments responsible for public safety, and how it is received by allied nations. Worse, refusing to confront these difficult truths—or branding legitimate concerns as Islamophobia—creates a vacuum, one readily filled by extremist voices and adversarial actors eager to poison and pollute the discussion.

Following such attacks, in addition to thinking first of the direct victims, I sympathize with my Muslim family, friends, colleagues, moderate Muslims worldwide, and Muslim victims of Islamic extremism, particularly given that anti-Muslim bigotry is a real problem they face. For Muslim victims of Islamic extremism, that bigotry constitutes a second blow they must endure. Personal sympathy, however, does not translate into an obligation to center Muslim communal concerns when they were not the targets of the attack. Nor does it impose a public obligation or override how societies can, do, or should process and respond to violence directed at them by Islamic extremists.

As it applies to the general public in Western nations, the principle is simple: there should be no expectation that non-Muslims consider Islam, inter-Islamic identity conflicts, internal theological disputes, or the broader impact on the global Muslim community, when responding to attacks carried out by Islamic extremists. That is, unless Muslims were the victims, in which case some consideration is appropriate.

Quite bluntly, non-Muslims are not required to do so and are entitled to reject and push back against any suggestion that they must or should. Pointedly, they are not Muslims, a fact far too many now seem to overlook.

The arguments presented here will be uncomfortable for many and will likely provoke polarizing discussion. Nonetheless, they articulate an important, human-centered position regarding how Islamic extremist attacks in Western nations are commonly interpreted and understood by non-Muslim majority populations.

Non-Muslims are free to give no consideration to Muslim interests at any time, particularly following an Islamic extremist attack against non-Muslims in a non-Muslim country. The sole exception is that governments retain an obligation to ensure the safety and protection of their Muslim citizens, who face real and heightened threats during these periods. This does not suggest that non-Muslims cannot consider Muslim community members; it simply affirms that they are under no obligation to do so.

The impulse for Muslims to distance moderate Muslims and Islam from extremist attacks—such as the targeting of Jews in Australia or foiled Christmas market plots in Poland and Germany—is understandable.

Muslims do so to protect their own interests, the interests of fellow Muslims, and the reputation of Islam itself. Yet this impulse frequently collapses into the “No True Scotsman” fallacy, pointing to peaceful Muslims as the baseline while asserting that the attackers were not “true Muslims.”

Such claims oversimplify the reality of Islam as it manifests globally and fail to address the legitimate political and social consequences that follow Islamic extremist attacks in predominantly non-Muslim Western societies. These deflections frequently produce unintended effects, such as strengthening anti-Muslim extremist sentiments and movements and undermining efforts to diminish them.

The central issue for public discourse after an Islamic extremist attack is not debating whether the perpetrators were “true” or “false” Muslims, nor assessing downstream impacts on Muslim communities—unless they were the targets.

It is a societal effort to understand why radical ideologies continue to emerge from varying—yet often overlapping—interpretations of Islam, how political struggles within the Muslim world contribute to these ideologies, and how non-Muslim-majority Western countries can realistically and effectively confront and mitigate threats related to Islamic extremism before the next attack occurs and more non-Muslim and Muslim lives are lost.

Addressing these realities directly is the only path toward protecting communities, confronting extremism, and preventing further loss of life.

Ian Bradbury, a global security specialist with over 25 years experience, transitioned from Defence and NatSec roles to found Terra Nova Strategic Management (2009) and 1NAEF (2014). A TEDx, UN, NATO, and Parliament speaker, he focuses on terrorism, hybrid warfare, conflict aid, stability operations, and geo-strategy.

The Bureau is a reader-supported publication.

To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Crime

Brown University shooter dead of apparent self-inflicted gunshot wound

From The Center Square

By

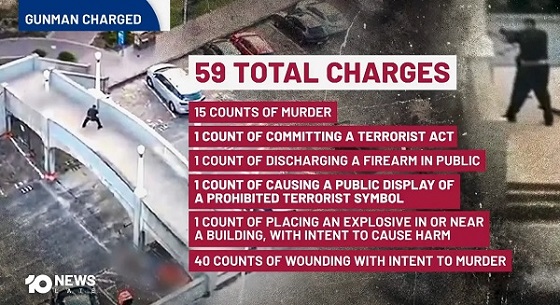

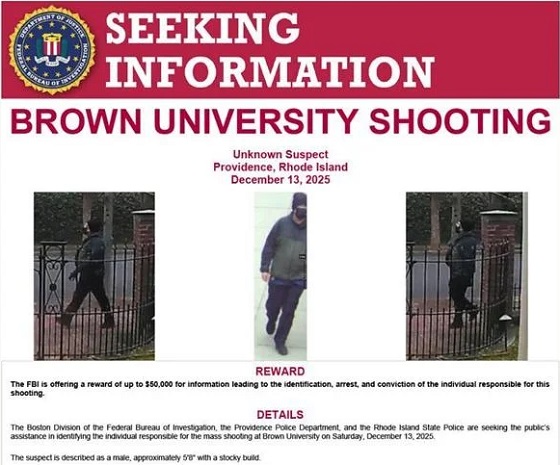

Rhode Island officials said the suspected gunman in the Brown University mass shooting has been found dead of an apparent self-inflicted gunshot wound, more than 50 miles away in a storage facility in southern New Hampshire.

The shooter was identified as Claudio Manuel Neves-Valente, a 48-year-old Brown student and Portuguese national. Neves-Valente was found dead with a satchel containing two firearms inside in the storage facility, authorities said.

“He took his own life tonight,” Providence police chief Oscar Perez said at a press conference, noting that local, state and federal law officials spent days poring over video evidence, license plate data and hundreds of investigative tips in pursuit of the suspect.

Perez credited cooperation between federal state and local law enforcement officials, as well as the Providence community, which he said provided the video evidence needed to help authorities crack the case.

“The community stepped up,” he said. “It was all about groundwork, public assistance, interviews with individuals, and good old fashioned policing.”

Rhode Island Attorney General Peter Neronha said the “person of interest” identified by private videos contacted authorities on Wednesday and provided information that led to his whereabouts.

“He blew the case right open, blew it open,” Neronha said. “That person led us to the car, which led us to the name, which led us to the photograph of that individual.”

“And that’s how these cases sometimes go,” he said. “You can feel like you’re not making a lot of progress. You can feel like you’re chasing leaves and they don’t work out. But the team keeps going.”

The discovery of the suspect’s body caps an intense six-day manhunt spanning several New England states, which put communities from Providence to southern New Hampshire on edge.

“We got him,” FBI special agent in charge for Boston Ted Docks said at Thursday night’s briefing. “Even though the suspect was found dead tonight our work is not done. There are many questions that need to be answered.”

He said the FBI deployed around 500 agents to assist local authorities in the investigation, in addition to offering a $50,000 reward. He says that officials are still looking into the suspect’s motive.

Two students were killed and nine others were injured in the Brown University shooting Saturday, which happened when an undetected gunman entered the Barus and Holley building on campus, where students were taking exams before the holiday break. Providence authorities briefly detained a person in the shooting earlier in the week, but then released them.

Investigators said they are also examining the possibility that the Brown case is connected to the killing of a Massachusetts Institute of Technology professor in his hometown.

An unidentified gunman shot MIT professor Nuno Loureiro multiple times inside his home in Brookline, about 50 miles north of Providence, according to authorities. He died at a local hospital on Tuesday.

Leah Foley, U.S. attorney for Massachusetts, was expected to hold a news briefing late Thursday night to discuss the connection with the MIT shooting.

-

International1 day ago

International1 day agoGeorgia county admits illegally certifying 315k ballots in 2020 presidential election

-

Alberta2 days ago

Alberta2 days agoAlberta project would be “the biggest carbon capture and storage project in the world”

-

Energy2 days ago

Energy2 days agoCanada’s debate on energy levelled up in 2025

-

Haultain Research1 day ago

Haultain Research1 day agoSweden Fixed What Canada Won’t Even Name

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoWhat Do Loyalty Rewards Programs Cost Us?

-

Energy2 days ago

Energy2 days agoNew Poll Shows Ontarians See Oil & Gas as Key to Jobs, Economy, and Trade

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoSocialism vs. Capitalism

-

Energy1 day ago

Energy1 day agoWhy Japan wants Western Canadian LNG